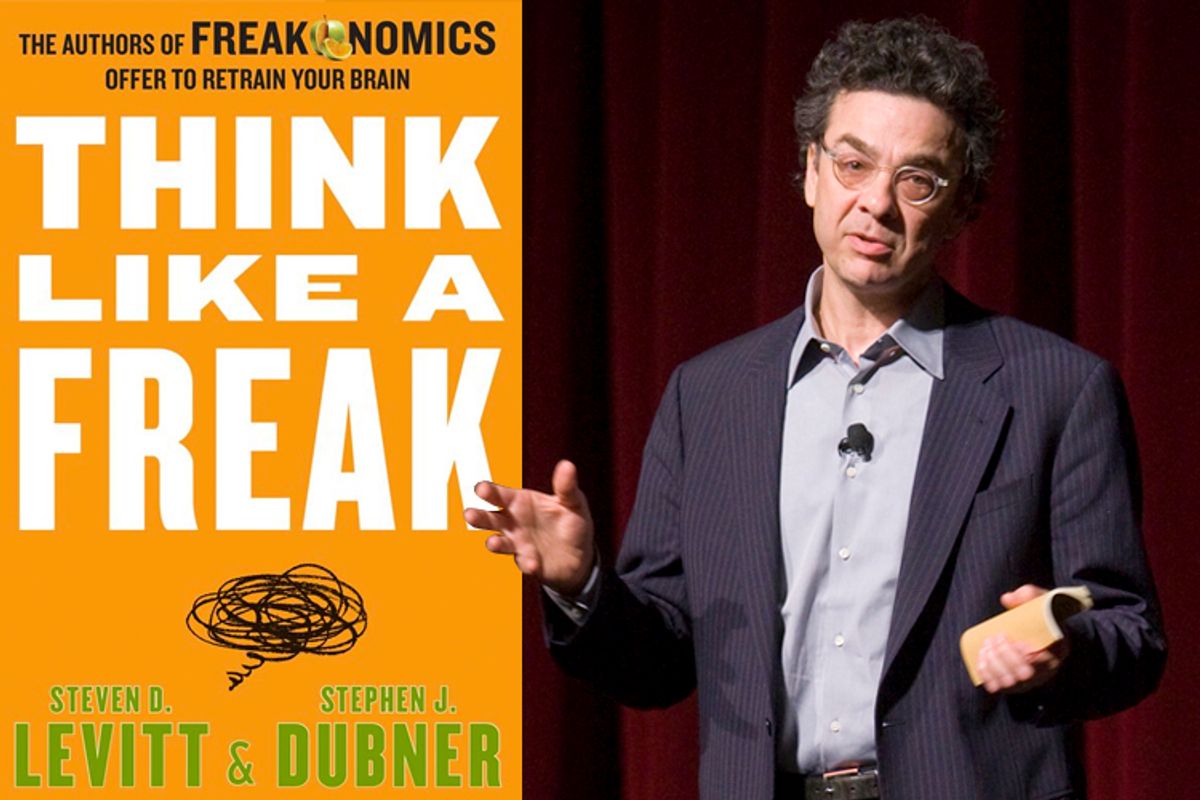

Stephen Dubner and Steven Levitt -- better known as the duo behind "Freakonomics" -- have written two best-selling books, produced a documentary and produce a popular blog and radio show. Now nine years after "Freakonomics" first splashed onto the scene, leaving plenty of adoration and controversy in its wake, they've released their third book.

In "Think Like a Freak," which is out today, the two steer away from the economics-applied-to-anecdote model of their first two books and hone in on how humans think. What's their prognosis? In short, they'd like us to drop the dogma, look more at the data, think more productively and more creatively.

What hasn't changed is the data-driven storytelling, and (almost too) straightforward approach to problems. In a conversation with Dubner, he explains why he and his partner moved away from their previous method and responds to critics who say they're oversimplifying. He also explains how thinking like a "Freak" can be applied to the world, and where it has its limitations. (Here's looking at you, cable news.)

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

After two successful books, a documentary, a blog and a radio show, why shift from the original model of applying economics to anecdotes and move into how we think?

So, I think we would have jumped off a cliff out of boredom if we just kept doing the same thing over again. I mean, even when it came time to write the second book, we weren’t sure we wanted to write a second book at all, and/or if it should be in the same model. But there was so much research going on that we did want to, and so we did.

But then we decided we really just didn’t want to do the same thing over again, and then for a while we thought we might not write a third book. But we really like working together, so we tried to come up with some ideas, and we came up with this one idea that for like five days was the most amazing book idea ever that anybody had ever had. But then, on the sixth day, we realized it was terrible. That it would just never work. So that was depressing.

And then, this one took a while. We had the idea. We really liked the idea, but then we thought it would be like a bunch of really short chapters -- really almost like a checklist. And then we decided that that book would not be fun to write -- it would be too self-help-y. We wanted to help, but it just wouldn’t feel like a good book.

And the first two books -- it’s not for us to say if they’re good or bad -- but at least as a writer, they’re really fun to write because they’re books; they’re narrative; they have flow; they have all that stuff that makes writing super fun. And so we came up with a way to kind of have a hybrid. Which is a sort of how-to book that still felt like writing a book. And you know, we do say in the very beginning of the book, it would have been great to answer every question and solve every problem that people sent us but it’s really hard. It’s really, really hard. It would take a hundred years, so rather than try to do that and fail, we thought wouldn’t be neat if we could sort of deputize anybody who wanted to do this? So that’s what we did instead.

How did you come up with the criteria for thinking like a "Freak"? Narrowing it down to these sort of specific ideas.

I like how you make it sound kind of scientific, like we had criteria that could be measured and weighed and put up to scrutiny. But mostly we sat around for many days early on and talked through these ideas. And there were many, many more. We must have had 50 to 100 “rules” that we thought about writing and then we just kept pushing at them and seeing which ones were most fundamental, which ones made sense, which ones stood up to scrutiny, which ones had interesting stories to attach to them. And those were the ones that we ended up sticking with. So yeah, I would say we probably threw away about 80-to-90 percent of the ideas we originally had, just because they didn’t seem that compelling.

It’s very interesting to hear that so much thinking went into the book, which is supposed to simplify your thinking. In writing any of these chapters, were there times where you realized that your rules applied to the writing of the book?

I think probably not. I think the only one that would sort of apply is the last chapter about the upside of quitting. As in, within the chapter on quitting we had this sort of very related section on failure, and the upside of failure -- the way to fail well, or to recognize failure for what it can be.

We hadn’t planned on writing a chapter about quitting, and what happened with that is we did a podcast about it, and for whatever reason that was just so much fun to do. In part because I had changed my life a couple times, quitting my band, quitting The New York Times, which doesn’t sound like a big deal, but for me it was a big deal because that was my dream job. The day I was hired at the Times, if you asked me, "In 30 years, will you still be working there?," I would have said absolutely, yes. So the idea that, five years later, I was ready to go surprised me. Levitt has quit a bunch of stuff, maybe not quite as drastic as those.

When we did that podcast, it was just so much fun because it was a great marriage of real economic concepts -- cost and opportunity cost -- with storytelling, which is what we like to do. And then so many people contacted us about that episode. It’s just obviously a topic that a lot of people think about a lot. And as a result of hearing from so many people who were so tormented about whether to quit, Levitt was inspired, and set up this whole "Freakonomics" experimental coin-flipping thing, which became its whole own thing. So that was the one chapter that was a little bit meta.

While we were writing the book, we were living that chapter. And it’s even related to, when we got to the end of the chapter, which was the end of the book, we put out the idea that maybe we should apply this to us. Maybe it’s time for us to quit this too, that we’ve done what we wanted to do, and if we’re out of ideas, or if we want to have totally different ideas. So I would say that’s the one chapter that we kind of lived while we were writing the book.

You guys talk a little bit about the fear of failure and being seen as a failure and that it's something that’s talked about a lot in Silicon Valley. I’m curious because in a lot of these chapters, I was reading and thought, "This seems very 'err...duh!'” It seems very simple. Like, "it’s okay to admit I don’t know, or it’s okay to think like a child, or to think small." But how do you think we shift the paradigm or shift the conversation into having it actually be okay to fail?

So first of all, was the phrase you used “err…duh!” ?

Yes.

Because that’s perfect. A lot of the stuff is things that we see as so obvious they’re barely worth saying. As you can just see looking around the world, people are just so busy doing their thing that they don’t spend a lot of time thinking, period. If there’s one lesson from the book, it’s just to spend one hour a week actually thinking. There’s just so much low-hanging fruit there.

I think in a way, Silicon Valley has probably gotten failure down better than anybody ever has. Partly it’s because the business model has been based in the price of failure. And I think that’s really key. So whether you’re on the start-up side or the investing side, or even another side, you understand that what you’re doing is kind of a science experiment here, and that most science experiments fail. And so therefore, if you’re on the investment side, you understand that if two of your ten companies work out well, then you’re fine. And therefore, failure is kind of expected. The problem is most of the world doesn’t really run like that.

So if you’re making government policy, for instance, you can’t afford an 80 percent fail rate, because a 10 percent fail rate gets so many bad headlines and so many arrows and slings from your political opponents that you’ll quit or commit suicide. The climate is just too brutal.

And I think in most business, failing is just not really accepted at all. And I think that’s partly because most businesses operate on a consensus model of argument where we’re gonna all get together and decide this is the right path, and it better work, and if it doesn’t work we have to pretend it’s working, and if anybody asks us how well it’s working we have to lie about it. And that’s just an awful way to operate. So, it’s so much nicer if you can build failure into your corporate culture.

This is a famous method by now: Google’s 20 percent time. The idea is that engineers who come there are encouraged, and sometimes almost required, to use 20 percent of their time to work on their own stuff, with the obvious admission that most of the things won’t be worth anything to the company. But once in a while they are, and a lot of Google’s best products have come out of 20 percent time. So I think you’re right that it is a paradigm shift but I would argue it’s hard not to see it as a potentially, as an almost inevitably, profitable and valuable paradigm shift that is long overdue.

You guys obviously have a lot of real world examples in the book – from Kobayashi, the hot-dog eating champion, to the guy who figured out how to cure ulcers. But how do you think that these methods can fit within the rest of the world? I kept thinking in the second chapter -- which was about admitting “I don’t know” -- what if both MSNBC and Fox News just admitted, “I don’t know”? You also talk a lot about dogma and other factors in play in the real world.

How do you see this book fitting within society? Is it possible to use “Think Like a Freak” and have it meld into the emotional, dogmatic, externally motivated way that humans generally think?

So that’s a really good question. I think the world is way too complex, and the incentives are way too varied from situation to situation, to expect that any one of the principles that we write about can necessarily be applied.

And what I mean by that is, in your example of MSNBC and Fox: Wouldn’t it be great if they would just say, "We don’t really know what this legislation would do"? So they have zero incentive to do that. And why? It’s because their business model is built to entertain their fans. I mean, I know that there are a lot of good journalists at both those places, but I also know that a modern news operation is a lot more like running a film studio or a rock and roll band or Cirque de Soleil than it is like in the old, idealized view of putting out “objective” news — if that ever indeed happened at all.

News has always been market-driven, and news has always been audience driven. And so look, I used to work at The New York Times, and I loved it, and one of the things I really loved about it was that it was close to the purest form of objective journalism as it exists today, and yet everybody knows it’s not very pure. There’s a million omissions and commissions everyday that reflect the hundreds of biases that are known and unknown. That’s just the way the human brain works.

So for someone like MSNBC and Fox to say ["I don't know"], they would immediately turn themselves into the most boring entertainers on TV, and their only incentive is to be the most exciting entertainers on TV. So I totally get that. And I’m not much for saying this is the way the world should be.

I know there are a lot of people who think cable news is a travesty. Whatever. There’s a lot of people worrying about that already. So I don’t know if “I don’t know” ideology can pertain to them. I do think there are other ideas I hope that we have, that could pertain to someone like them. So, in this chapter called “How to Persuade People Who Don’t Want to Be Persuaded," -- again, I have no idea if Fox or MSNBC specifically has any interest in this, probably not, but maybe so. Because if you think "I have 1 million viewers now and I could have 1.5 million if I siphoned off some of the other camp," that might be good.

So I really think we’ve identified a lot of things in that chapter about how bad people are at trying to persuade anybody of anything -- in part because they’re so sure that they’re right about everything that the minute that someone who has an opposing view hears ten words out of their mouths, they fail. They’re not serious people, they’re not informed people, they’re not intelligent and I’m turning them off immediately. So I do think there’s a lot of potential in learning how to persuade better. That said, it’s incredibly hard, so maybe they’re better of not even trying.

Yeah, that was an interesting chapter. I kept thinking about how a lot of the times it was mentioned in the book that you guys had come up against critics, and that “thinking like a freak” might not be the most popular response. I think it was in the first chapter, you say that you can’t tell a nice family that you just met that they shouldn’t have a car seat. How do you guys respond to your critics? There are some who have critiqued the completely data-driven way of thinking, or say that these methods are oversimplifying. Do you have any response?

Sorry, who says that?

Oh, it was Malcolm Gladwell who said that he did not always agree with economic or data-driven --

I think it would be a sad, pathetic world if people didn’t argue with the kind of things that we write, or the kind of things that anybody writes. Preferences generally are diverse. Not everybody sees the world the same way, not everybody wants to see the world the same way. Do you we tend to use data to try to make sense of human motivations? Of course we do. That’s kinda part of the deal.

Do we however recognize that pure data gathering and analysis is inchoate — is one tool in the whole arsenal of trying to actually understand and explain human behavior? Yeah, I would say we do.

People having arguments about methodology. I think 10 people in the world really care about that. That’s the kind of thing that makes a lot of noise, but the only people who care are the people who are actually doing it themselves. Which is, academic arguments in academia are so loud and so incredibly uninteresting to anyone but the 10 people having the argument. I do think when we raise hackles about issues, I tend to be more interested in that.

Real estate agents got really upset with us last time, or in our first book. And their argument was, well, "I see why you say what you say by looking at the data, but real estate agents sell their own homes, they hold out longer and they get more money. But that’s because we bought better homes in the first place and we know how to show them." Although the data doesn’t support that. We would say well, we controlled for how nice the homes are. And then the conversations with the realtors would become, "Okay, let’s be honest, I know a lot of realtors who do that but I don’t do it." So everybody becomes the exception to the rule that they don’t like.

We try our best to not be preachy and to not tell people how they should behave. But we also try our best to illuminate the ways in which so many decisions get made and the way so much business gets done that just isn’t very wise, whether it’s wise for social justice or wise for profit or whatnot. Criticism is so fine with me. Gary Becker, who was one of Levitt’s big mentors, died this week.

Yeah, I was going to mention that.

Gary, as we’ve probably written 10 times, was the godfather of everything we do. He was the first guy to apply economic thinking to non-economic topics. And for many years he was just ridiculed and reviled. People said, "You’re not really an economist; go join some sociology department." Sociologists didn’t want him. Very unpopular for many reasons with some people. And then 30 or 40 years later, he wins the Nobel Prize, and now he’s considered one of the all-time greats in economics. And Gary’s view was if you’re not talking about something that occasionally makes some sets of people upset then you’re wasting your time. I think being inert and being complacent are far greater sins than stirring up the pot now and again. So, yeah. We welcome criticism.

A lot of the book is based on data, and the use of data to solve problems. How do you source your data? Is there a specific methodology that you've developed? Do you ever worry that data is reductive?

Levitt's methodology, and that of economics generally, is fairly rigorous but of course every data set and the interpretation thereof needs a lot of interpretative and contextual help to make sure it's saying what you think it's saying. No, the final number isn't always the simple answer. Yes, one worries about data being too reductive. That said, using aggregated data is generally more useful than relying on tendentious anecdote.

Did you intend for these to be taken as a whole, or is it to display different methods for you to say, "I could try to apply this to my life"? And then do you have one that you personally think is important?

That’s a good point. I think we had a line in the book in some draft about how, surely no one person would find value in all of these ideas, but hopefully most people would find some value in a couple. But I think that line ended up going away, which seems kind of a shame now that you asked that question.

So do I have a favorite chapter? My favorite single story is the story of Kobayashi. But I’m biased, I recognize, because I’ve just come to like him as a human so much, so I don’t know if anybody else would really like that story. But I think he’s a remarkable and interesting and kind and charismatic human, so I loved writing that story.

I think my favorite chapter, although I’ll give you a caveat in a minute, is the one about King Solomon and David Lee Roth, "Teach Your Garden to Weed Itself." And I love it because I just love tricks. And I love the idea that it’s like invisible ink or something — figuring out a way to do something that just doesn’t appear on the surface, but that said, here’s my caveat on that one. Most people don’t really get the opportunity to pull those kinds of tricks, because they’re for specialized situations.

So if there’s one chapter I had to say was most valuable or applicable and useful to people, it would be “Think Like a Child,” just because it’s easy, it’s doable, it’s almost free to do and I think it’s got a lot of upside to it, once you start to do it. So again, thinking, just period. Spending any time thinking is better than none, but especially if you can get in touch with your inner 8-year-old and not be intimidated by all the jargon that you’ve been swamped by, all the better.

When we were talking about quitting, I was struck earlier (rather surprised) by you saying: "We put out the idea that maybe we should apply this to us, maybe it’s time for us to quit this too, that we’ve done what we wanted to do, and if we’re out of ideas or if we want to have totally different ideas." What is the future for you -- more projects? Or is this it?

We do have a number of projects lined up, including the ongoing Freakonomics Radio, but if those projects don't seem to be working to our satisfaction, we will likely be willing to jettison them quite quickly.

Shares