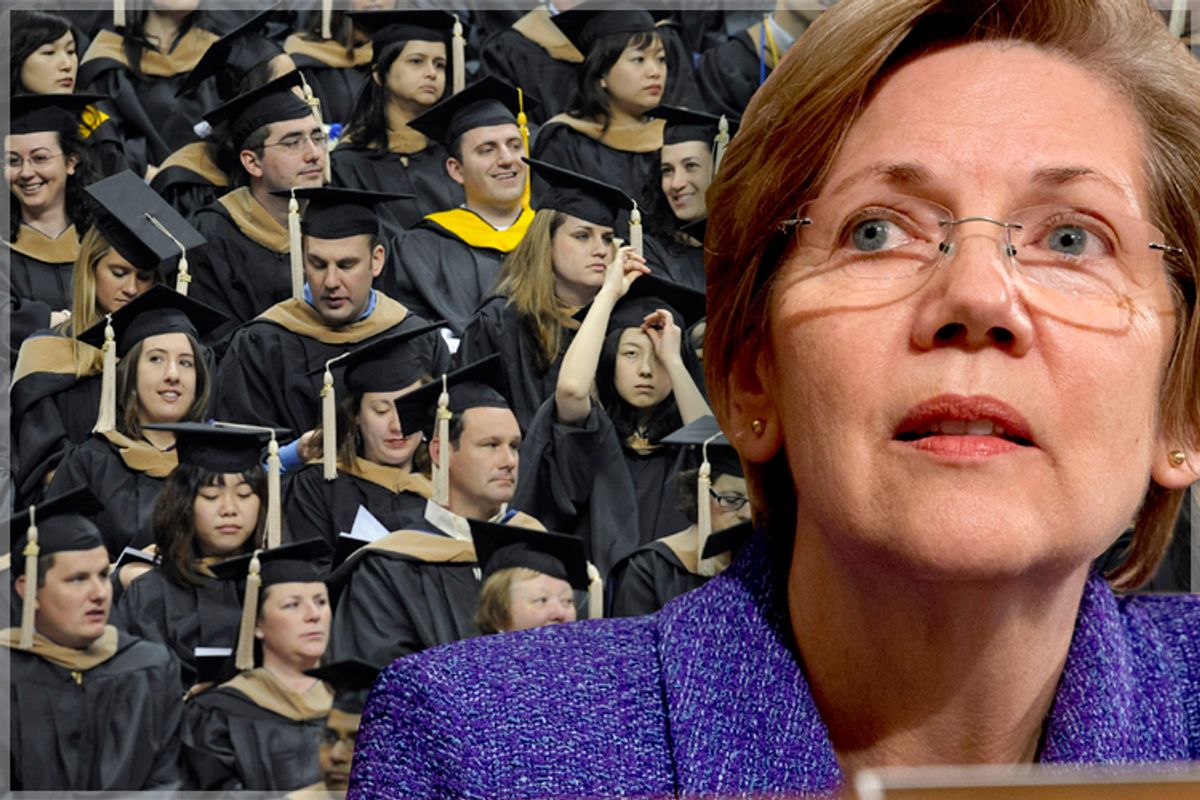

In the latest volley in the ongoing debate over what to do about student loans, Sen. Elizabeth Warren recently introduced a bill that would allow borrowers to refinance old student loans with a federal one at today’s lower interest rates (i.e., 3.86 percent, 5.41 percent or 6.41 percent, depending on the type of loan). The bill, of course, offers the rate cut to address the staggering volume of student loan debt and increasing default rates, while also seeking to address recent revelations that the federal government is “reaping profits” on its growing portfolio of student loans.

Although at first pass, cutting interest rates seems to be a sufficient response to excess profit-making interest, Warren’s bill will not and cannot fully eliminate the problem.

Given the ineliminable possibility of federal profits, what students borrowers need is legislative assurance that any excess revenues generated from the student loan program will be cycled back into services and programs for student borrowers.

There is some disagreement about the numbers, but the Government Accounting Office (GAO) recently estimated that the government will generate $66 billion in profit on the $454 billion in loans it originated between 2007 and 2012. The GAO estimates that for every $100 in student loans the government issued to recent borrower cohorts, it may generate between $13 and $16 in profit after all administrative and write-off costs are accounted for.

These numbers depend on any number of assumptions — how the economy is doing, and student repayment rates, among others. They are, at best, an attempt to predict a hazy future. But the predictions demonstrate the real possibility for billions in federal profits.

The government has not faced this public policy issue on such a massive scale before. Up until 2010, the majority of federal student loans in the United States were in fact issued by private lenders and merely guaranteed by the federal government. Profits from these loans went to the third party holders — mostly banks and secondary purchasers such as Sallie Mae. In 2010, President Obama eliminated this program — called the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program—requiring that the federal government itself originate all new federal student loans. He said:

Under the FFEL program, taxpayers are paying banks a premium to act as middlemen, a premium that costs the American people billions of dollars each year. Well, that’s a premium we cannot afford, not when we could be reinvesting that same money in our students, in our economy, and in our country.

Thanks to this 2010 switch, we have cut out the middleman. But we haven’t cut out the profits. They are just going to the federal government rather than private third parties. In recent testimony before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, the Chief Operating Officer of Federal Student Aid said that these profits are “used to fund the government generally. They do not come back specifically into the [student loan] program.”

Letting the federal government fund other programs with revenues from student loan debt is not in the spirit in which President Obama wound down the FFEL loan program, nor does it comport with Americans' spirit for access to higher education. The government should not be lining its coffers by lending to students trying to get an education. We value too much what education does for the individual and what education does for our society as a whole.

Warren’s bill is a nice gesture towards addressing the problem of federal profits, but marginally reducing interest rates will not eliminate government profits. According to the GAO, the (admittedly hard-to-calculate) break-even interest rate for this year’s borrowers is a mere 2.52 percent.

In fact, by refinancing the $250 billion in old FFEL loans that are currently held by third parties through the federal program at rates like 3.86 percent, 5.41 percent and 6.41 percent the government may well increase its overall profits.

Moreover, trying to cut interest rates alone will not solve the problem. The break-even rate is too hard to calculate and too variable. In a gesture towards bureaucratic transparency, the title of the GAO report on the topic is in fact called “Borrower Interest Rates Cannot Be Set in Advance to Precisely and Consistently Balance Federal Revenues and Costs.”

Indeed, the closer the government tries to match the estimated break-even rate, the higher the possibility that the program may end up running a deficit, adding a political challenge given today’s climate. Plus, there is little political will to again adjust student loan rates. We barely got out of the summer of 2013 with a deal.

As a result, any plan to try to deal with the student loan profit question must anticipate that there will be some — apparently significant — buffer of revenues. The revenues are bound to exist, but they need not be booked as profit for the government. We should instead ensure that they are cycled back into student borrowers themselves. Student loan revenues should be a closed system: the money should not be siphoned off to the “government generally,” but should rather go to help current and future generations of student borrowers.

Once the student revenues are closed off, the Department of Education could establish an advisory panel to monitor loan cash flows and redirect the money to any number of initiatives — such as decreasing future interest rates or rebating the money back to student borrowers.

Another possibility to consider is that the money be used to provide access to student debt discharge in bankruptcy — which is currently very difficult to attain, even when other consumer debt is cancelled. Using the money to change this portion of the bankruptcy code would change the excess interest payments into an insurance premium that provided value to each borrower. Each student would pay for the possibility that their post-graduate lives may take a wrong turn and that that they would need access to improved opportunities for debt relief.

Of course, use for the excess student loan revenues will depend on gaining a clear understanding of how much money is actually coming in the door and whether there is the necessary political will to help the worst-off borrowers get their fresh start. Either way, the crucial first step is clear: we need to establish a system to ensure that the money is cycled back into student borrowers.

By offering students the opportunity to refinance at slightly lower interest rates, Warren is starting the conversation on government profit in the student loan market. But the bill’s marginal changes do not go far enough, and a proposal to alter the interest rates alone will never suffice. Congress should close the system of student loan profits and put the money revenues back into the student borrowers who need it most.

Right now, four years after the 2010 switch to all federally-originated loans, we are seeing the first cohort of students with their entire loan portfolio on government books walk across the stage, get their diploma and enter loan repayment on the other side. Promising them that the federal government will not profit on their loans is a graduation gift they deserve.

Shares