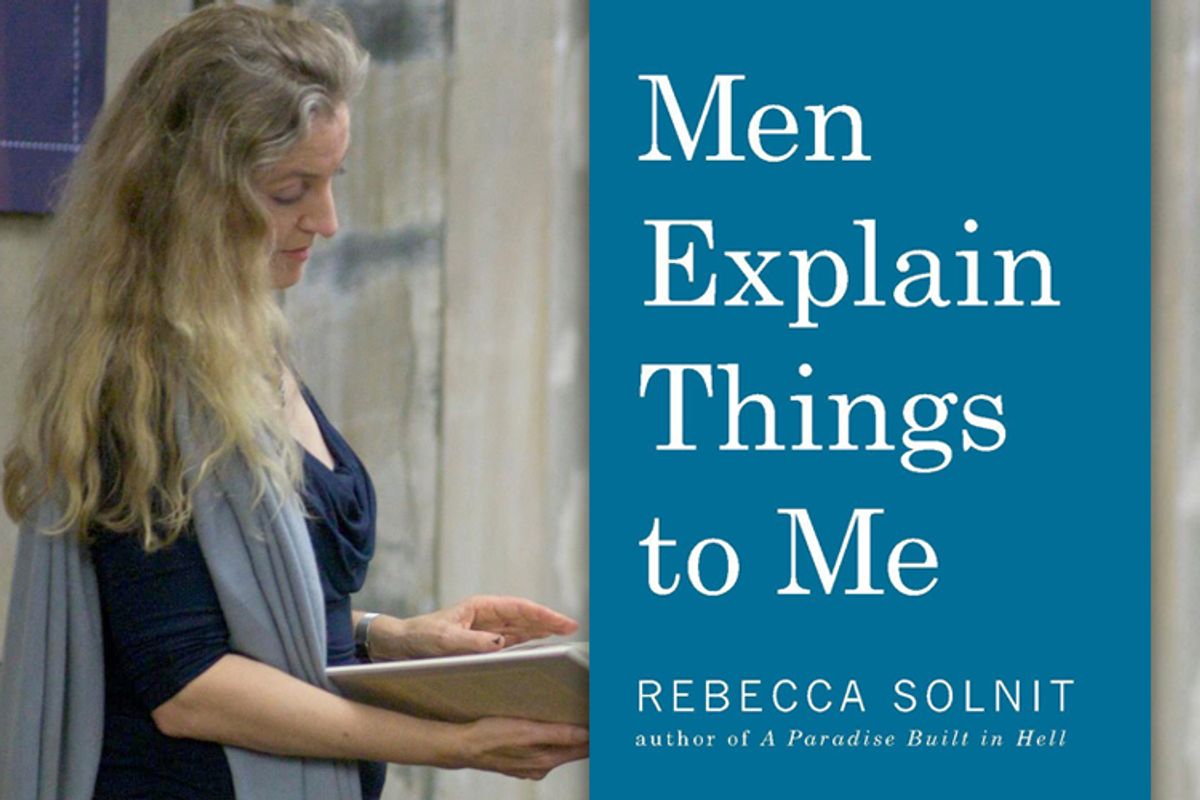

Rebecca Solnit is a decorated author and activist, but she may be best-known for the word she added to our lexicon: “mansplaining.” Mansplaining was born from a 2008 blog post in which Solnit wrote: "Men explain things to me, and other women, whether or not they know what they're talking about." Since then, "mansplaining" has taken the culturesphere by storm, getting named one of the New York Times' "words of the year" and inspiring countless think pieces. Solnit has been writing elegant, sharp essays and books for more than two decades -- her latest book, also called "Men Explain Things to Me," released today, is a collection of seven essays about this particular facet of the modern gender wars. On the whole her work spans a broad spectrum of subjects ranging from literature, art, philosophy, anti-militarism and the environment. It is feminist, frequently funny, unflinchingly honest and often scathing in its conclusions. In 2010, the Utne Reader named Solnit, who is the recipient of several literary awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Lannan literary fellowship, one of 25 Visionaries Who are Changing Your World.

Tell me about writing that first essay from which the name of the book is taken, "Men Explain Things to Me." As you mention in the book, it is a piece that continues, years after publication, to be shared and discussed.

I’d been joking about writing it for years. Men explaining things to me had been happening my whole life. The infamous incident I described -- in which a man talked over me to explain a Very Important Book he thought I should read that it turns out I wrote -- happened five years earlier in 2003.

The term “mansplaining” has resonated with so many women. It shifted the cultural universe ever so slightly (in a good way). Did you expect this response?

You know, I had a wonderful conversation about a month ago with a young Ph.D. candidate at U.C. Berkeley. I’ve been a little bit squeamish about the word “mansplaining,” because it can seem to imply that men are inherently flawed, rather than that some guys are a little over-privileged, arrogant and clueless. This young academic said to me, “No, you don’t understand! You need to recognize that until we had the word 'mainsplained,' so many women had this awful experience and we didn’t even have a language for it. Until we can name something, we can’t share the experience, we can’t describe it, we can’t respond to it. I think that word has been extraordinarily valuable in helping women and men describe something that goes on all the time.” She really changed my opinion. It’s really useful. I’ve always been interested in how much our problems come from not having the language, not having the framework to think and talk about and address the phenomenon around us.

Your work has always focused on sexualized and gender-based violence. The second essay in your book, "The Longest War," is based on one you wrote in the wake of the Delhi and Steubenville rapes. What are your thoughts on mainstream media narratives regarding rape and domestic violence? Do you think we are at an inflection point globally in public discourse surrounding these subjects?

Yes, I really do. Remember when Nicole Brown Simpson was murdered, more than 20 years ago? That started a conversation about domestic violence and how often it becomes lethal and how horrific and oppressive and terrifying and discriminatory it is. Then O.J. Simpson lawyered up, in the way that incredibly rich men that do awful things to women do, like Dominique Strauss-Kahn, or the recent case of the billionaire Gurbaksh Chahal, who recently got off on probation after allegedly hitting his girlfriend 117 times on camera. There are just so many times when other kinds of hate crimes get the attention they deserve, and I never feel that we shouldn’t pay attention to other kinds of hate crimes, but I’ve just waited and waited and waited for violence against women to be treated as a hate crime.

Last year I organized a campaign demanding that Facebook recognize violent misogynistic expression as hate speech, and it was clear that the idea of gender-based hate was a difficult one for many people to wrap their heads around. Why do you think that is?

It’s interesting to see how hard a time people have seeing that as a problem in this way. I mean, replace any number of words -- “Jewish,” “gay,” “black" -- with “woman” in terms of violence, and people often find it unacceptable to hate on or even threaten or despise the group. But women: it's a free ride, often. I really felt, though, like the New Delhi murder in 2012 was a watershed moment. That and Steubenville felt different. These were not treated as unique terrible crimes that have nothing to do with anything else. That’s the way that each case about rape or domestic violence is usually portrayed. We have three murders of women a day at the hands of their partners. These are supposed to be isolated incidents so that we don’t have to focus on the culture and no one has to talk about changing the system or addressing patriarchy and masculinity. The term "rape culture" has been useful.

What is different?

It’s because young women on campuses are doing brilliant networked organizing around rape and campus sexual violence. It’s because young women are speaking up. It’s because feminist voices are really coming of age. Engaged voices are changing the media coverage and not accepting the “Oh, it’s her fault. What was she wearing? Why was she there? She should just lie back and enjoy it.” One of the things that is most notable about 2012 was that all five of the Republican candidates who said exceptionally stupid and obnoxious things about rape lost their elections.

Can you talk about a theme you regularly return to, the obliteration and disappearance of women -- physically, artistically, politically?

The last essay of the book is very much about the fact that feminism is an attempt to change thousands of years of patriarchy, silencing, subjugation, erasure and containment of women. The fact that in less than half a century we’ve so radically transformed the social landscape is amazing. It’s one of the things that I’ve been trying to articulate in my mostly hopeful work. When I was born a little over half a century ago there was no “sexual violence,” “marital rape,” “domestic violence,” “sexual harassment,” “sexual discrimination.” None of those expressions existed and none of these things were treated as legal categories. "Kitty" Genovese could be stabbed to death in public and many looked away thinking the guy had the right to do it, because, it turns out, they thought the murderer was her husband or partner.

Ivy League colleges, where the power brokering of this country takes place, did not admit women, something we don’t talk about nearly as much as we talk about non-white people being barred from colleges of the South. When Anita Hill appeared in Congress. the current vice president was one of her attackers, but, something happened in between, and he’s been one of the main sponsors of the Violence Against Women Act. Some people say we can rest on our laurels. We haven't won, we haven't lost, we’re winning some of the battles -- the war is not over. Let’s keep going, but, let’s feel confident and excited about what we’ve accomplished, where we might go, and who our allies are.

Shares