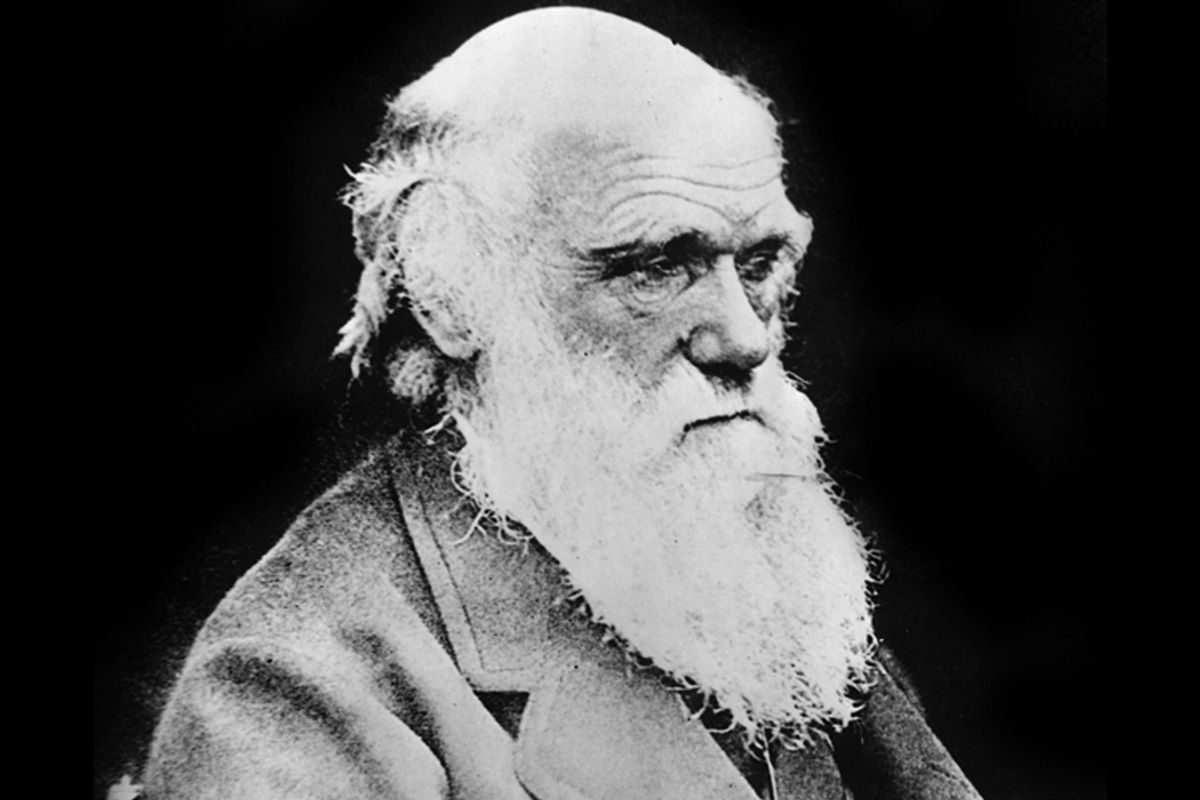

In "The Descent of Man," Charles Darwin offered his views on the origin of morality, and nothing in the past century and a half suggests the great man got it wrong. In his view, primeval tribes with “a great number of courageous, sympathetic, and faithful members,” who stood ready to warn, aid, and defend each other, outcompeted tribes dominated by “selfish and contentious people.” As Darwin saw it, group selection on the African savannah explains both human cohesiveness and our moral instincts.

He wrote that “our moral sense” originates “in the social instincts, largely guided by the approbation of our fellow-men, ruled by reason, self-interest, and in later times by deep religious feelings, and confirmed by instruction and habit.” Our sense of justice is, for the most part, preloaded or innate owing to our savannah ancestors who practiced cooperation and survived droughts, disease, and occasional attacks by warring bands to successfully pass their genes on to subsequent generations.

Although Darwin’s theory of group selection still has its skeptics, Jonathan Haidt is not among them. In "The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion," Haidt says the result of this process is that humans have become “the giraffes of altruism.” Our evolutionary path has left us as “one-of-a-kind freaks of nature” when it comes to our willingness to engage in selfless behavior for the benefit of our groups. Recently, brain scans have allowed us to see how behavior consistent with our own sense of justice activates our reward (dopamine-driven) systems. In short, seeing justice done makes us feel good.

But, as the psychological research makes clear, our sense of justice also is significantly affected by our culture and experiences, beginning at a very early age. As children, we learn through experience how to recognize unfairness (in an uneven distribution of cookies, perhaps), cruelty (in the unprovoked beating of a friend by a bully), and how to distinguish appropriate lies (“white lies”) from those that are contemptible. In the hundreds of social situations that present themselves to us as we age, we learn, through our successes and our failures, which behavioral responses are most likely to produce the most satisfying results.

EMOTIONS, REASON, AND OUR SENSE OF JUSTICE

The more researchers learn about the human brain, the more persuaded they are that emotion not only influences our perceptions and thoughts but is also integrated into the processes of thought at the level of our neurological circuitry. Our moral judgments, including our sense of justice, emerge from a bath of emotions. That is not to say, however, that reasoning has no role to play. If reason and our sense of justice were completely disconnected, it would be hard to account for the existence of the countless courses in ethics and moral reasoning that appear in college catalogs.

Neuroscientists at Princeton used brain scans to see whether emotions or reason mattered more in determining how people deal with moral dilemmas. The Princeton researchers administered MRI scans to subjects while presenting them with “the Trolley Problem,” a moral dilemma first posed by philosophers in the 1980s. The researchers asked what should be done when a runaway trolley is about to hit and kill a group of five people, but where a nearby switching device could, if pulled, divert the trolley car unto a sidetrack, saving the group of five but—and here’s where the dilemma arises—dooming another person who is standing on the sidetrack. Presented with this situation, the vast majority of respondents pull the switch, sacrificing the single individual but saving the five. When the facts are changed, however, and the group of five can only be saved by pushing an obese “stranger” onto the tracks, thereby causing the train to derail before the imminent collision, most people come to the opposite conclusion: they choose not to act, dooming the five, but sparing the life of the stranger.

What’s going on here? Brain scans showed that the thought of pushing a person onto tracks in front of an onrushing trolley caused emotional parts of subjects’ brains to light up like crazy. Even for those subjects who ultimately decided to make the push, the decision took considerably longer to make than when the question was whether to pull the lever. The lesson is that it takes time and effort for our cognitive brain to overrule our emotional brain, and the more active our emotional brain is, the longer the delay will be. As the Trolley Problem research shows, our emotional brains and cognitive brains sometimes point in opposite directions. For every Mr. Spock who sees saving five for one as the right choice, there is someone else who is thankful we have brain circuitry that gets so tangled up at the thought of killing people that we choose not to.

We make moral judgments only after processing by both the emotional and cognitive parts of our brains. Some people, because of their brain circuitry, will incline toward utilitarian (less emotion-driven) judgments, while others make judgments guided more by guilt, compassion, and other emotions. Despite what law professors and others might have told you, there is no reason to assume that the more “reasoned” a judgment is, the better it is. Although we sometimes say the person who makes the more “impersonal” decisions has “risen above” her emotions to reach the right result, it is just as likely that she is making a serious mistake. Evolution had reasons for bathing our decision-making process in emotions. In law school you were supposedly taught “to think like a lawyer”—but we should give ourselves permission to think, first and foremost, like humans. This is especially true when a lot is on the line. Sigmund Freud might have had it about right when he said, “In the most important decisions of our personal life, we should be governed, I think, by the deep inner needs of our nature.”

Morality is concerned with “should” questions: Should I agree to represent an unpopular defendant when to do so might damage my practice? Should I tell the police about my concerns that my client is planning a fraud? Should I demand that opposing counsel provide me with a huge stack of documents, even though I know the costs of assembling that information far outweigh whatever small benefits they might have for my case? We use both reason and emotion to decide these moral questions, but mostly we use emotion.

Your sense of justice as a lawyer, although refined by years of law school and legal experience, is still—like everyone else’s—strongly influenced by your emotional brain. When opposing counsel comes back with an insultingly low offer, your brain will flash “punish the bastard!” before—if there is a before—your cognitive processing kicks in and you begin to weigh the possible costs of a punitive response. Being a good lawyer, in no insignificant part, comes from learning—through trial and error—when to punish and when to forgive, when to fight and when to retreat, when to raise your voice and when to lower it, when to empathize and when to detach.

PURSUING JUSTICE, BUT WITH INTEGRITY

Lawyers, more so than most any other professionals, need strong moral cores because of the temptations they regularly face to lie, deceive, or fudge. Being straight about the facts of a case or being honest and direct in dealing with a valued client who proposes an ethically questionable course of action is often the harder course to take.

“We Don’t Blur!”

Earlier we met John Doar, who worked courageously for the cause of equal rights in the Deep South of the 1960s. Doar was also a great respecter of truth. One of his former assistants at the Justice Department, Howard Glickstein, remembered discussing strategy in a voting rights case with Doar. There were two ways of presenting the case to the court, Glickstein recalled. One way was to straightforwardly present the facts. The other way was to blur the facts in a way that somewhat strengthened the government’s position. When Glickstein suggested to Doar that they adopt the second approach, Doar sat up straight in his chair. “Absolutely not!” he said. “You just present the facts as they are. We represent the United States of America. We don’t blur!” Doar was so sincere and so well prepared that judges “took anything that came out of his mouth as the Gospel truth.” His careful, thorough approach and soft-spoken arguments bordered on being dull, but “with all the emotionally charged rhetoric of the time, being dull could be very effective.”

THE IMPORTANCE OF HONESTY

Blurring tempts all lawyers at various times in their careers, but Doar did the right thing for a Justice Department lawyer (especially) to do. To blur or not to blur: that is a moral question? Yes, choosing to be completely forthright in a brief—not “blurring” the facts, as Doar insisted—might reduce the chances for a favorable court decision (or might not, with astute enough judges), but for Doar, principle trumps the desire to win.

Honesty has long been considered an important value, of course. We all have heard the (apocryphal) story involving a young George Washington and the cherry tree he supposedly chopped down. Telling his father he cut down the tree required overcoming fears about a probable punishment. But young George, guided by a moral principle that would help lead him to future greatness, tells the truth anyway. Another president, Abraham Lincoln, also placed a high value on honesty. In 1850, Lincoln offered this advice to new law students: “There is a popular belief that lawyers are . . . dishonest. [But] . . . [l] et no [one] choosing the law for a calling . . . yield to the popular belief—resolve to be honest at all events; and if in your own judgment you cannot be an honest lawyer, resolve to be honest without being a lawyer.”

The belief among the public that lawyers as a group are dishonest has changed little since Lincoln’s time. A 2011 Gallup Poll that asked over 1,000 Americans to rank professions by their “honesty and ethical standards” found that only 19% of respondents thought the honesty and ethics of lawyers ranked either “very high” or “high.” In comparison, 84% of the public thought nurses had very high or high levels of honesty. Judges did considerably better than lawyers (47% thought them honest in a similar 2010 poll), and even real estate agents, bankers, and reporters scored better than lawyers. Only a handful of jobholders, including advertisers, members of Congress, car salespeople, and lobbyists, were thought to be more dishonest and unethical than lawyers.

Clearly, we have some work to do in the area of public perception. Cheating sometimes helps you win, as most lawyers know. Not every trial judge will impose sanctions, even when he or she strongly suspects a lawyer deserves them. And, of course, many times cheating won’t be discovered at all, or it will be discovered too late. When a lawyer is not punished for being dishonest and the client benefits from his dishonest actions, the inclination is strong for the lawyer to keep doing it. No one wants to lose a case or an important client. Doing the right thing takes courage.

We need to remember the words of one experienced trial lawyer, who said the goal of great lawyers is not just to win—it is to win “with honor.” “Honor” may have an old-fashioned ring to it—the American sense of morality has evolved—but character still matters, especially in the legal profession, where both the opportunities and incentives for justifying ethically questionable conduct are great.

Excerpted from "The Good Lawyer: Seeking Quality in the Practice of Law" by Douglas O. Linder and Nancy Levit. Published by Oxford University Press. Copyright 2014 by Douglas O. Linder and Nancy Levit. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares