In the spring of 1775, the inhabitants of the thirteen colonies were forced to make a choice between loyalty to the existing government of King George III or the hope of a less oppressive political structure. Perhaps most troubling, the lines between colonists loyal to the king and those advocating rebellion were not clearly drawn, and this uncertainty made for uneasy relationships, particularly among families, neighbors, and friends. In the absence of a united groundswell of popular uprising, the political situation was complicated, and it carried with it an ugly overtone of civil war.

Who were the true patriots — rebels who fought for a change of government or loyalists who stood by their sovereign? In hindsight, American propagandists would glory in the term patriot for those who had risen up against British oppression and apply Tory in a derogative fashion to those who fled the country, fought against them, or merely tried to avoid the fray. The political labels of Whigs and Tories were also applied. But at the beginning of 1775, rebels or loyalists were the terms usually employed.

Either way, mere labels could not adequately convey the emotional cost to personal relationships. Jonathan Sewall and John Adams were lawyers, close friends, and intellectual confidants. As early as 1759, it was Sewall who, sensing the financial burdens that Great Britain would impose on the colonies after the French and Indian War, encouraged Adams to write his first political letters for publication. “Mr. Sewall was then a patriot,” Adams later recalled. “His sentiments were purely American.”

But as the divide between the colonies and the Crown deepened, highly placed loyalists aggressively courted Sewall. Over time, they promoted his law practice and saw to his appointment first as solicitor general for the province and later as attorney general. Adams eschewed such offers, but he and Sewall “continued our friendship and confidential intercourse, though professedly in boxes of politics as opposite as east and west,” until just after Adams was chosen as a delegate to the First Continental Congress.

In that summer of 1774, finding themselves in court together in what is now Portland, Maine, the two old friends went for an early morning walk. Sewall was vehement in opposing Adams’s participation in the congress. “Great Britain was determined on her system,” Sewall lectured his friend; “her power was irresistible, and would certainly be destructive to [Adams], and to all those who should persevere in opposition to her designs.” But Adams was equally determined. “The die was now cast,” Adams replied. “I had passed the Rubicon; swim or sink, live or die, survive or perish with my country, was my unalterable determination.” The two men parted, and each took his own path, not to meet again as friends.

Families suffered similar rifts. Colonel Josiah Quincy, a Boston merchant of some standing, had three sons. The eldest, Edmund, followed his father into business and adopted his political leanings, becoming “a zealous whig” and political writer during the Stamp Act crisis. There is little doubt Edmund’s persuasions and activities would have continued had he not died in 1768 at the age of thirty-five. The second son, Samuel, went to Harvard and became a lawyer. As with Jonathan Sewall, Samuel Quincy was courted by loyalists and later appointed solicitor general of Massachusetts. As a family biographer later delicately noted, “Influenced by his official duties and connexions, his political course was opposed to that of the other members of his family.” The third son, Josiah Quincy Jr. (sometimes referred to as Josiah Quincy II), also went into law but picked up where his brother Edmund had left off. Josiah became a blazing though short-lived meteor of rebel rhetoric, which culminated in a strident pamphlet published in May of 1774 in which he argued against the bill closing the port of Boston. Josiah sent a copy to Samuel, who, while opposing his brother’s views, rather mournfully acknowledged, “The convulsions of the times are in nothing more to be lamented, than in the interruptions of domestic harmony.”

Later that fall, while John Adams was in Philadelphia for the Continental Congress, his wife, Abigail, who was a distant Quincy relation, dined at Colonel Quincy’s home in Braintree and found Samuel’s wife, Hannah, and the junior Josiah and his wife, another Abigail, present. Hannah remarked that “she thought it high time for her husband to turn about; he had not done half so cleverly since he left her advice” and stood by the loyalists. It is not entirely clear whether Samuel himself was there for this family gathering, but Abigail Adams reported to John, “A little clashing of parties, you may be sure.” Josiah junior was likely rather discreet on the occasion, as he was even then planning to leave in several weeks on a secret trip to London in an attempt to rally friendly merchants and members of Parliament to the rebel cause.

Just how deeply divided a region might be was evidenced in and around Marshfield, a community of about twelve hundred inhabitants roughly halfway between Boston and Plymouth. The town had a long history of outspoken loyalty to Great Britain and in the aftermath of the Boston Tea Party had passed a town resolution decrying the action as “illegal and unjust and of a dangerous Tendency.”

In mid-January of 1775, one hundred and fifty Marshfield residents voted against supporting the trade edicts of the Continental Congress. Instead, they voiced support for an association promoted by Timothy Ruggles, a Massachusetts lawyer who had been president of the 1765 Stamp Act Congress but who was now a staunch loyalist. The Ruggles Covenant, as some called it, promised that its signers would do everything in their power to enforce “obedience to the rightful authority of our most gracious Sovereign; King George the third, and of his laws.”

To that end, Marshfield residents formed a local militia to counter those of the rebels and called themselves “the Associated Loyalists of Marshfield.” But when this became known down the road in Plymouth, “the faction there,” as one loyalist termed the rebel movement, threatened to march en masse and either force the Marshfield loyalists to recant or drive them off their farms. Marshfield appealed to General Gage for assistance, and Gage dispatched four officers and about one hundred men via two small ships to Marshfield along with three hundred stands of arms “for the use of the gentlemen of Marshfield.”

This response had the desired effect, and when the local rebel militia attempted to muster in opposition, “no more than twelve persons presented themselves to bear Arms” against the king. As another loyalist gloated, “It was necessary that some apology should be made for the scanty appearance of their volunteers, and they coloured it over with a declaration that ‘had the party sent to Marshfield consisted of half a dozen Battalions, it might have been worth their attention to meet and engage them.’”

Meanwhile, the British troops were quartered outside Marshfield on the fifteen-hundred-acre estate of Nathaniel Ray Thomas, one of the mandamus councilors scorned by the rebels. “The King’s troops are very comfortably accommodated, and preserve the most exact discipline,” boasted the same observer. And to the rebels’ chagrin, they showed no inclination to leave anytime soon. To the loyalists, the troops provided an extra measure of security in town so that “now every faithful subject to his King dare freely utter his thoughts, drink his tea, and kill his sheep as profusely as he pleases.” (One of the Continental Association’s many mandates in preparing for a full-scale boycott against Great Britain was to prohibit the slaughter of sheep under the age of four, a measure intended to build domestic flocks.)

General Gage was quite pleased by this request for assistance from Marshfield. While he was forced to acknowledge that despite his efforts, “the Towns in this Province become more divided,” Marshfield was a glowing example of local opposition to the rebels. “It is the first Instance of an Application to Government for assistance,” Gage reported to Lord Dartmouth, “which the [rebel] Faction has ever tried to perswade the People they would never obtain.”

Even though they had not put up a military resistance to Gage’s rescue of Marshfield, rebels in nearby towns did not take this intrusion of British regulars lightly. Selectmen in six towns in the county of Plymouth petitioned General Gage to remove the public disgrace they felt the military deployment reflected upon their county. Swearing a regard for the truth that they claimed their adversaries had overlooked, these representatives asserted that the fears and intimidation of Marshfield residents “were entirely groundless” and that “no design or plan of molestation was formed against them.” This petition came from the neighboring towns of Plymouth, Kingston, Duxbury, Pembroke, Hanover, and Scituate, and one look at the map showed that, at least geographically, the rebels had Marshfield surrounded.

And even in Marshfield there was not unanimity. At a subsequent Marshfield town meeting — with British regulars still encamped near town—a motion was put forth to determine whether the town would support the resolves and proclamations of both the Continental Congress and the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. It failed to pass, and instead the town voted letters of thanks to General Gage and Admiral Samuel Graves of the Royal Navy for their prompt support. But sixty-four Marshfield residents, being “sensible of the high colouring which the Tories never fail to bestow on every thing that turns in their favor,” boldly protested not only the results of the vote but also the procedures of the town meeting. The Marshfield selectmen — three assumed loyalists — “gave but a day’s warning for the said Meeting” and ordered it held without notice of the agenda in a location where a town meeting had never been held before.

It was little wonder that when the Provincial Congress met in Concord in February, there was no representative present from Marshfield, and the congress thanked the six rebel towns of Plymouth County for “detecting the falsehoods and malicious artifices of certain persons belonging to Marshfield.”

But the loyalists of Marshfield and elsewhere had good reason to be concerned. The rebel movement possessed a very ugly side. Boycotts, protests, and propaganda were one thing, but intimidation, abuse, and physical violence were quite another. Even as Plymouth rebels were joining neighboring towns in assuring General Gage that Marshfield loyalists had nothing to fear, Plymouth loyalists were under assault. When loyalist women gathered at a meeting hall for a social event, a mob surrounded the building and threw stones, breaking shutters and windows. When the ladies attempted to flee to the supposed safety of their homes, they were “pelted and abused with the most indecent Billingsgate language.” (Billingsgate, a section of London that was home to a fish market of the same name, was known for its foul talk and seamy ways.)

Even if one tried to keep a low profile, any association with the royal government posed a risk. Israel Williams, “who was appointed of his Majesty’s new Council, but had declined the office through infirmity of body” — or quite possibly out of fear of reprisal — was nonetheless “taken from his house by a mob in the night, carried several miles, put into a room with a fire, the chimney at the top, and doors of the room being closed, and kept there for many hours” until he was literally smoked. He barely made it out alive.

“To recount the suffering of all from mobs, rioters, and trespassers, would take more time and paper than can be spared for that purpose,” one loyalist said in an appeal to the Provincial Congress after a lengthy listing of intimidations and destruction of property. “It is hoped the foregoing will be sufficient to put you upon the use of proper means and measures for giving relief to all that have been injured by such unlawful and wicked practices.”

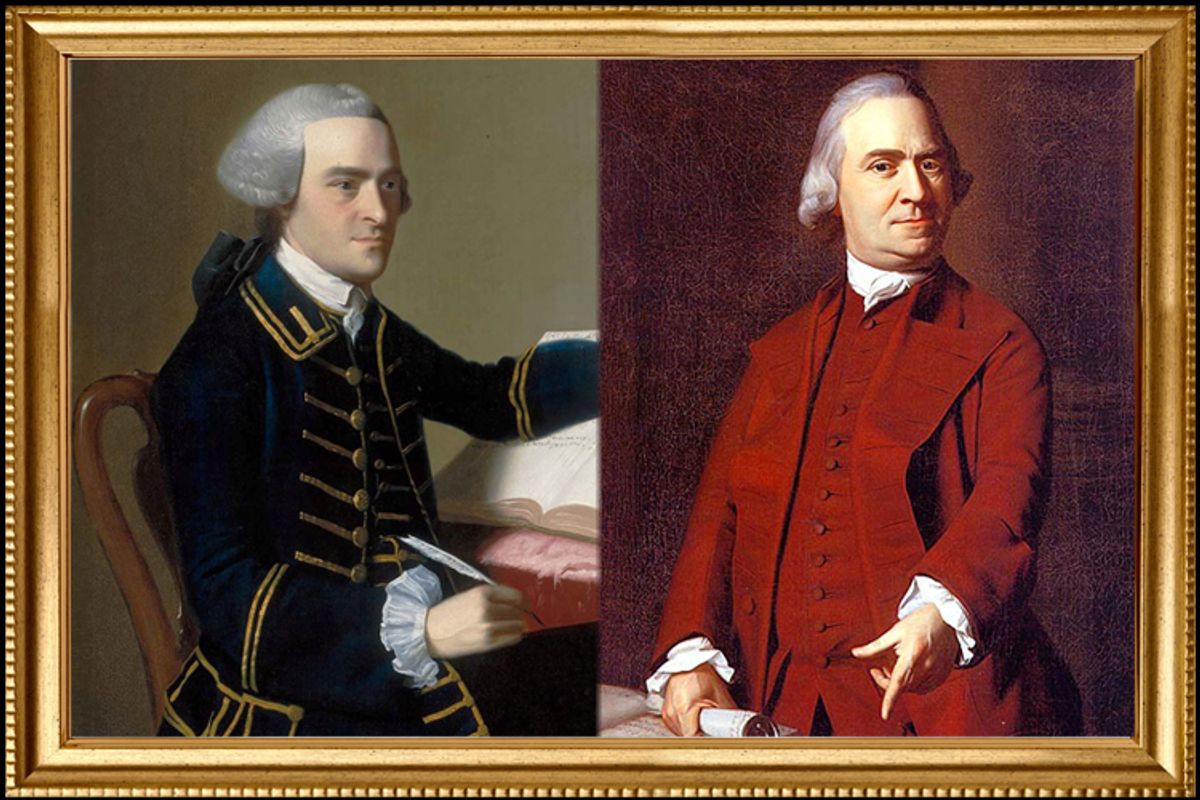

Since the Provincial Congress then assembled in Concord was decidedly pro-rebel, such loyalist pleas fell on deaf ears. The congress had recently elected John Hancock its president, and its pro-rebel sentiments were fueled in large part by the machinations of Samuel Adams. What an interesting pair they were.

John Hancock was supposed to have become a Congregationalist minister; he would have been the third generation of John Hancocks to be so ordained. His grandfather, the first John, was so widely known and respected among Congregationalists in Massachusetts that he unofficially came to be called the Bishop of Lexington. The “bishop” saw to it that his eldest son, the second John, went to Harvard, as he had, and after serving three years as a librarian there because he could not find a ministry, the second John was finally ordained and established in a church in Braintree. The new minister took his time, but seven years later, in December of 1733, he married a local farmer’s daughter. When their second child and first son was born on January 12, 1737, there was little doubt that his name, too, would be John Hancock.

Among their neighbors was the family of Deacon John Adams, which included a son, also named John, who was two years older than the youngest John Hancock. The two boys would sometimes play together, but years later John Adams would remember his playmate with some exasperation. Young Hancock “inherited from his father,” John Adams wrote, “a certain sensibility, a keenness of feeling, or — in more familiar language — a peevishness that sometimes disgusted and afflicted his friends.” But, allowed Adams, “if his vanity and caprice made me sometimes sputter . . . mine, I well know, had often a similar effect upon him.”

Young Hancock’s inclination to outbursts of temper and self-importance probably came more from his grandfather, the bishop, than from his father. Grandfather John put so much emphasis on his eldest son’s education and well-being that his second son, Thomas, was sent to Boston at the age of fourteen to become an apprentice in a bookbinding business. The ministerial path was clearly the prestigious one, and grandson John was groomed for it from an early age. But then the bishop’s long-range plans fell apart.

The second John died suddenly just short of his forty-second birthday, leaving a widow and three small children. Grandfather John invited them to live with him in the manse at Lexington. It was tight financially, but the combined family attempted to make the best of it. A few months later, a handsome carriage, drawn by four matched horses and attended by four liverymen, pulled up. Who should alight but Thomas, the bishop’s second son, who twenty-seven years previously had left home in poverty. Not only had the bookbinding business proven profitable but a partnership with one of Boston’s leading merchants and subsequent shrewd investments had also turned Thomas Hancock, apprentice, into Thomas Hancock, respected merchant. In addition to his trading empire, the House of Hancock, Thomas had a wife, his partner’s daughter, Lydia, and a mansion on Beacon Hill. About the only thing Thomas didn’t have was an heir after thirteen years of trying.

Thomas Hancock’s offer was too good to pass up. He would provide his father and his brother’s widow and children with additional income if young John, then age seven, would come to Boston to be raised as his and Lydia’s own. Thus John Hancock went from a Congregational manse in Lexington to a mansion on Beacon Hill and detoured forever from the path his grandfather had laid out for him. Instead, he would follow his uncle Thomas into business.

In only twenty years, Thomas Hancock had built the House of Hancock into a lucrative conglomerate. Starting with the book-binding business, it had quickly grown to include publishing, paper manufacturing, and Boston’s most complete general store. There was nothing that his shelves did not contain or that he could not get — for a price. His ships plied the Atlantic with cargoes of rum, cotton, fish, whale oil, and more. He came to own warehouses and wharves along Boston’s harbor. And, as did many successful businessmen, he negotiated profitable government contracts, providing food, munitions, and supplies to various military expeditions, including William Pepperell’s 1745 expedition against the French at Louisbourg.

What didn’t change in John Hancock’s young life after moving in with Uncle Thomas and Aunt Lydia was that he was still bound for Harvard. After graduating in 1754, he entered his postgraduate training at the House of Hancock. The French and Indian War was brewing, and once again Thomas was a key military supplier. Grooming John for an eventual partnership, his uncle sat him down in the ledger room and began to reveal the complex transactions that had turned the House of Hancock into such a powerhouse. Only Thomas and John had access to all the accounts and records. His shrewd uncle “had set up the books so that no one clerk could put the entire puzzle together and become a competitor.”

As the war wound down, Thomas and Lydia sent John to London not only to collect on some of his uncle’s overseas accounts but also to give him a certain cultural polish. This graduate course in monetary negotiations stood John in good stead, but he almost failed his uncle’s expectations of personal economy. “I find Money some way or other goes very fast,” John wrote Thomas somewhat apologetically. “But I think I can Reflect it has been spent with Satisfaction and to my own honour.”

John enjoyed London’s refinements and was inclined to linger there, but Thomas was beginning to feel his age, particularly after Lydia’s father, who had been Thomas’s mentor and patron, fell ill and died. Thomas and Lydia wanted their nephew safely back in America, and John arrived in Boston on October 3, 1761, having been away sixteen months.

That winter Thomas, too, fell ill, and it scared him. He put more and more control of the business into John’s hands and a year later, on New Year’s Day of 1763, announced to his associates that he was taking “my Nephew Mr. John Hancock, into Partnership with me having had long Experience of his Uprightness [and] great abilities for Business.”

With his uncle’s blessing, over the next months John readily took ever greater control of the affairs of the House of Hancock, no doubt exhibiting some of that ego and intransigence that John Adams recalled as “peevishness.” Nineteen months after making John a partner, in August of 1764, his uncle died suddenly of a stroke as he made his way into a meeting of the Governor’s Council. He left generous bequests to Lydia, relatives, and community causes, but the prize of his estate, the House of Hancock and its many properties, he left solely to his nephew John, whom “he had loved as a son” and who was now at age twenty-seven suddenly one of the wealthiest men in America and Boston’s undisputed merchant king.

But there was more. Hancock buried his uncle on the Monday after his death; five days later, his Aunt Lydia handed him a deed to the family mansion, its furnishings, and the Beacon Hill land on which it sat, requesting only that she be allowed to live out her life there. Having always adored his aunt, John was happy to honor her proposal. Lydia became Hancock’s hostess, his social conscience, and—when he seemed to drag his feet in choosing a suitable wife — his matchmaker.

All this set up John Hancock as an example of profound paradox when it came to the mounting tension between Great Britain and its colonies. Hancock had everything he could possibly want under the British colonial system. True, a tightening of the customs laws and ever-higher taxes threatened to take some of his wealth away. But thanks both to his uncle’s legacy and his own innate knack for business, John Hancock was the epitome of success in colonial America. Yet, in perhaps even more of a paradox, a decade later the rank and file of rebels in Massachusetts—be they the farmers of Lexington and Concord or the blue-collar tradesmen of Boston, who would readily burn the mansions and businesses of entrenched loyalists — would come to revere the likes of John Hancock, who was as elite and patrician as anyone.

So how was it that John Hancock, merchant king, came to be John Hancock, rebel leader? The answer lies in part with a ne’er-do-well former tax collector, failed businessman, and part-time brewer named Samuel Adams. Few men were further apart in business practices, but each had a personality that thrived on risk. In addition — and this was perhaps easier to read on Adams’s coarse veneer than on Hancock’s polished sophistication — each man could be calculatingly cold and purposeful.

Samuel Adams was born on September 16, 1722, and was fifteen years Hancock’s senior. There has been a tendency among historians to call him, familiarly, Sam — especially given the popularity of a certain twentieth-century brewing company—but the contemporary evidence points strongly to the fact that he was “Samuel.” Indeed, the modern incarnation of the brand of beer that bears his name, made by the Boston Beer Company, is officially “Samuel Adams.”

As young Samuel entered Harvard, at fourteen, his father, the elder Samuel Adams, was well on his way to joining Thomas Hancock on the top rung of Boston’s power-broker ladder. Samuel senior used his brewery operations to cement ties to local taverns and, in turn, the political types who gathered there, eventually founding a political machine called the Boston Caucus. His next venture was a rural bank outside Boston that circulated its own paper money to farmers based on the value of their lands and crops. It was a rather creative approach at a time when hard currency, in the form of British sterling, or barter — either one of which was available through the House of Hancock — held sway. But it ran counter to the established norm, backed by certain merchants under the leadership of Thomas Hutchinson. At their urging, Parliament outlawed the land bank, indicted its organizers — including Samuel senior — and ordered all money bought back with Massachusetts currency. Samuel senior lost a good share of his life’s savings, and his son, who was then in his third year at Harvard, swore eternal revenge on Thomas Hutchinson.

But young Samuel’s problem was that he did not seem to have the golden touch that Thomas and John Hancock did. After Harvard, Samuel went to work for a merchant friend of his father’s, but he was fired for spending more time writing political rants than keeping the company’s books. Despite his own financial straits, Samuel senior bankrolled his son so that he could start his own venture, but Samuel junior loaned half the stake to a friend, who promptly lost it; young Samuel then lost the other half on his own. The son tried his hand in the family brewery, but once again reveled in the political discussions of the taverns more than he attended to business.

His father died soon afterward. Adams squandered much of his inheritance, leaving both the brewery and his father’s mansion in marginal condition. Political cronies of his father at the Boston Caucus tried to bail him out in 1756 by arranging his appointment as Boston tax collector. But that didn’t work, either. Within a year, Adams owed the town for taxes that he had either failed to collect or had collected and carelessly allowed to drop into his own pocket.

His second cousin John Adams recalled that Samuel once acknowledged to him that he had “never looked forward in his life; never planned, laid a scheme, or formed a design for laying up any thing for himself or others after him.” That was likely true when it came to his shabby personal finances — which in any event Samuel blamed not on his own shortcomings but on a festering hatred for Thomas Hutchinson and the merchants of his class. It was certainly not true, however, that Samuel was a laggard when it came to laying the foundation for a political scheme.

And when it came to politics, Samuel Adams did not pull any punches. At the time, the only man in Massachusetts more vociferously against British rule than Samuel Adams was James Otis, a firebrand attorney whose revolutionary role was cut short by mental illness. (Otis’s married sister, Mercy Warren, was as yet too busy raising children to think about adding her own pen to the fray.) Adams and Otis were both fiercely independent, champions of individual liberties, and ardently antiestablishment.

What pushed the seeming opposites of Samuel Adams and John Hancock together was money — or, more precisely, the lack of it in the post–French and Indian War period. With the French driven from Canada and Indian affairs west of the Appalachians relatively calm after the defeat of Pontiac’s Rebellion, there was no one left to fight. This meant that there were no more lucrative government contracts for the House of Hancock or anyone else. In good times, the additional taxes levied by the Stamp Act might have been swallowed, but in this postwar depression, they loomed large and were the catalyst for Samuel Adams to rally opposition to all things British.

In addition to his pen, Adams’s arsenal included his personal influence over an increasing number of fellow rebels. Taken at their best, they formed an idealistic corps devoted to self-government; at their worst, they roamed the streets as an unruly mob. When it was announced that the Stamp Act collector for Boston was to be Andrew Oliver, a well-to-do merchant who happened to be Thomas Hutchinson’s brother-in-law, the mob took over. Oliver was hung in effigy from an elm tree on High Street that would soon be called the Liberty Tree. Then these rowdies marched on Oliver’s house. Oliver had long fled with his family, but the marchers broke down the doors and ransacked its contents.

Among those who abhorred this violence was John Hancock. Oliver was a fellow merchant and Harvard graduate. If such a mob could vent anger on Oliver’s mansion, what was to stop them from marching up Beacon Hill to Hancock’s own stately residence? While Samuel Adams thought that the night’s events “ought to be forever remembered . . . [as] the happy Day, on which Liberty rose from a long Slumber,” Hancock beseeched his agent in London to do all he could to encourage repeal of the Stamp Act, which he called “a Cruel hardship upon us,” in the interest of avoiding further violence.

His torn interests put Hancock decidedly on the fence. He began to spend more and more time in Boston taverns, including the Green Dragon, headquarters of his Masonic lodge. He wasn’t being driven to drink; rather, he sought firsthand intelligence on how the political winds were blowing. Samuel Adams routinely stopped by the Green Dragon on his tavern rounds, and before long he began to spin his dreams of political rebellion in the younger man’s ear. From 1758 to 1775, Adams “made it his constant rule,” according to his cousin John, “to watch the rise of every brilliant genius, to seek his acquaintance, to court his friendship, to cultivate his natural feelings in favor of his native country, to warn him against the hostile designs of Great Britain, and to fix his affections and reflections on the side of his native country.”

This Samuel Adams did in spades with John Hancock. Never mind that Adams was still under scrutiny for his deficiencies as tax collector. Hancock soon decided that the best way to protect his property and business interests — not only on Beacon Hill but also throughout Boston and its waterfront — was to guarantee their safety by funding part of Adams’s growing political movement — rowdy though it might be at times.

In October of 1765, Hancock joined 250 British merchants, among whom he was clearly a kingpin, in supporting a boycott of British goods until the Stamp Act was repealed. For Hancock it was definitely a win-win. With the depressed economy, his business was at low ebb. His remaining credit in London was nil, and he could not have ordered a shipload of British goods if he had wanted to. Joining the boycott gave him an excuse to unload existing inventories at bargain prices. The boycott was actually good for his business, and it made him look like a hero to the Adams crowd. As for his own debts, he craftily pointed out to his London agent that without stamps, “he was legally unable to issue any remittances.”

It helped John Hancock immensely that he was well liked by his hundreds of employees and related operators who depended on his many businesses. By one later estimate, perhaps a little high, “a thousand families were, every day in the year, dependent on Mr. Hancock for their daily bread.” So when Hancock showed up at the Green Dragon, or any other establishment in Boston, the rank and file sang his praises as someone who treated them kindly and honestly.

In the end, the people hurt the most by this boycott were British merchants whose flow of orders from America and accounts receivable from past business took a substantial dip. By one account, British exports to the colonies dropped 14 percent, and London merchants pleaded with Parliament as readily as did their American cousins to consider “every Ease and Advantage the North Americans can with Propriety desire.”

A wealthy planter in Virginia who was watching events throughout the colonies held a similar view. “I fancy the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the colonies, will not be among the last to wish for a repeal of the act,” George Washington wrote to the uncle of his wife, Martha, in London. As for Hancock, he declared to his London agent “that not a man in England, in proportion to estate, pays the tax that I do.” He would not be a slave, Hancock declared. “I have a right to the Libertys & Privileges of the English Constitution, & I as an Englishman will enjoy them.”

With Adams’s blessing and the support of the Boston Caucus, Hancock won a seat in the Massachusetts legislature, polling five votes more than Adams himself received in his own race. Hancock thought that he was championing commercial freedom, but what his election really did was bring him to the full attention of the government in London, which now identified him as “one of the Leaders of the disaffected.” This impression was particularly solidified when, in one of Hancock’s tavern campaign talks, he had boasted that he “would not suffer any of our [English customs] Officers to go even on board any of his London ships.”

Out for a walk that election day, John Adams happened to run into cousin Samuel and they took “a few turns together.” Coming in view of Hancock’s mansion on Beacon Hill, Samuel pointed to the impressive structure and remarked to John, “This town has done a wise thing to-day. They have made that young man’s fortune their own.”

Ten days later, lightning struck. One of Hancock’s ships docked in Boston with news that Parliament had repealed the Stamp Act. Samuel Adams’s mob — dignified in some circles by the name Sons of Liberty — set off a huge fireworks display on Boston Common. Then they marched on John Hancock’s Beacon Hill property, just as Hancock had once feared. But now they came to crown Hancock the hero of the hour for championing the boycott. He responded with fireworks of his own “in answer to those of the Sons of Liberty” and set out a pipe of Madeira wine — a cask of about 125 gallons — to treat the crowd. The only casualty of the night occurred when a giant wooden pyramid bedecked with lanterns, which had been erected on the Common, caught fire by accident and burned to the ground.

The end result was that John Hancock and Samuel Adams emerged from the Stamp Act crisis as somewhat unlikely political partners. As the years went by, there would never be any question which side they were on. Others would vacillate, even up until the final hour, but together Hancock and Adams would stay the course toward rebellion and, ultimately, independence. As for those who wavered in their views, “Their opinions,” noted Samuel’s cousin John with disgust as he sat down to the First Continental Congress, “have undergone as many changes as the moon.”

Excerpted from "American Spring: Lexington, Concord and the Road to Revolution" by Walter R. Borneman. Published by Little, Brown and Co. Copyright © 2014 by Walter R. Borneman. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares