In a Times Op-Ed earlier this year about the trend of prosecutors using rap lyrics written by defendants as evidence against them in criminal trials, Erik Nielson and his co-author wrote: “It is easy to conflate these artists with their art [and] it becomes easier still when that art reinforces stereotypes about young men of color — who are almost exclusively the defendants in these cases — as violent, hypersexual and dangerous.” Nielson, who teaches courses on hip-hop culture at the University of Richmond, has become an international expert on this increasingly common phenomenon: the use of rap lyrics in court. Nielson’s Op-Ed was largely based on the research from his article “Rap on Trial,” recently published in Race & Justice. He has testified for the defense in the California case of Alex Medina, was expert witness on the recent double murder trial of Virginia rapper Twain Gotti, and is scheduled to testify in several other upcoming cases.

When did prosecutors first begin introducing rap lyrics of defendants as evidence, and how often are they being used?

We’ve been able to find cases going back to the early 1990s, but it’s hard to say precisely when prosecutors first began doing this. One of the problems is that trial proceedings and court opinions are not published in any kind of systematic way. When I first started researching this issue, I thought I could go into some legal database like Lexis Nexus, type in “rap lyrics,” and get a list of cases. It doesn’t work like that. I’ve tried.

We’re interested in more than just trials — we want to know when lyrics are being used throughout the criminal justice process. We know, for example, that prosecutors are using the lyrics during indictment proceedings, sentencing hearings, and even in less formal ways -- like using the lyrics as leverage to get defendants to take a plea bargain.

How successful, generally, has it been as a means toward conviction?

Very successful. That’s why prosecutors keep doing it! There’s actually some empirical evidence out there that demonstrates the prejudicial effect rap lyrics can have on jurors.

Now, in some cases, it’s honestly tough to say with certainty that rap lyrics alone led to a conviction, especially if they are just one of many pieces of evidence in the prosecutor’s case. But we’re seeing cases where the prosecutor’s evidence is extremely weak, and that’s when the rap lyrics become really powerful. The recent New Jersey case that’s now being considered by the state Supreme Court — State v. Vonte Skinner — is a perfect example.

This guy Skinner was charged with attempted murder for his alleged role in a shooting, but during his trial, prosecutors had very little evidence except some rap lyrics that he had written. What’s crazy is that the lyrics were written months — even years — before the shooting, none of them mentioned the victim, and none contained specific details of the crime. But the judge, seemingly asleep at the wheel, allowed the D.A. to read, uninterrupted, 13 pages of violent rap lyrics. Big shock: Skinner was found guilty. He’s doing 30 years.

We’re seeing this kind of thing all the time. Even worse, we’re seeing more and more cases where rap itself is the crime.

Is this institutional racism at work or has the culture of gangsta rap (as opposed to rap in general) contributed to this phenomenon?

Both, but institutional racism needs to be front and center in these discussions for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that gangsta rap was, and still is, very much a response to racism!

Look, I’ve been getting frustrated at times by the way discussions about this have been playing out. Don’t get me wrong; the rules of evidence, First Amendment protections and other legal issues are extremely important. But they are misguided if they aren’t framed in some way by the central issue here, which is the racism that persists in society generally and within our justice system in particular. Rap music is the only form of fictional expression being targeted this way in court, even though plenty of artistic genres are full of violence. If a body turns up in Maine, do we think police and prosecutors will start pouring over Stephen King’s novels so they can pin the crime to him? If Russell Crowe gets arrested for assault (again) and he goes to trial, do we think the D.A. will trot out “Gladiator,” arguing that it’s evidence of his motive or intent to commit violence?

But prosecutors use [rap] all the time and often tell jurors to interpret the lyrics as if they were diary or journal entries. Often a “gang expert” — a police officer — will assert his or her authority to talk about rap music and will parrot the prosecutor’s arguments: These lyrics are confessions.

Why does this work?

I think many people are unable to view rappers, predominantly young men of color, as artists in the first place, and when their rap lyrics also present an image of a hypersexualized, violent, even pathological figure, that image maps neatly to preexisting stereotypes, especially about young black men.

I don’t deny that gangsta rap has unique vulnerabilities. The need to create a sense of authenticity — of “keepin’ it real” — often results in real problems in court. If you’re still acting the part of your rap persona even when you’re offstage, you may know that it’s a P.R. strategy, but people who don’t know rap might not.

For centuries, we’ve pathologized black people, punished black artists, and more recently, we’ve begun warehousing record numbers of black and Hispanic men (and women) in prison. When we talk about rap on trial, I don’t want to hear about rules of evidence or the Constitution unless we’re having this conversation as well.

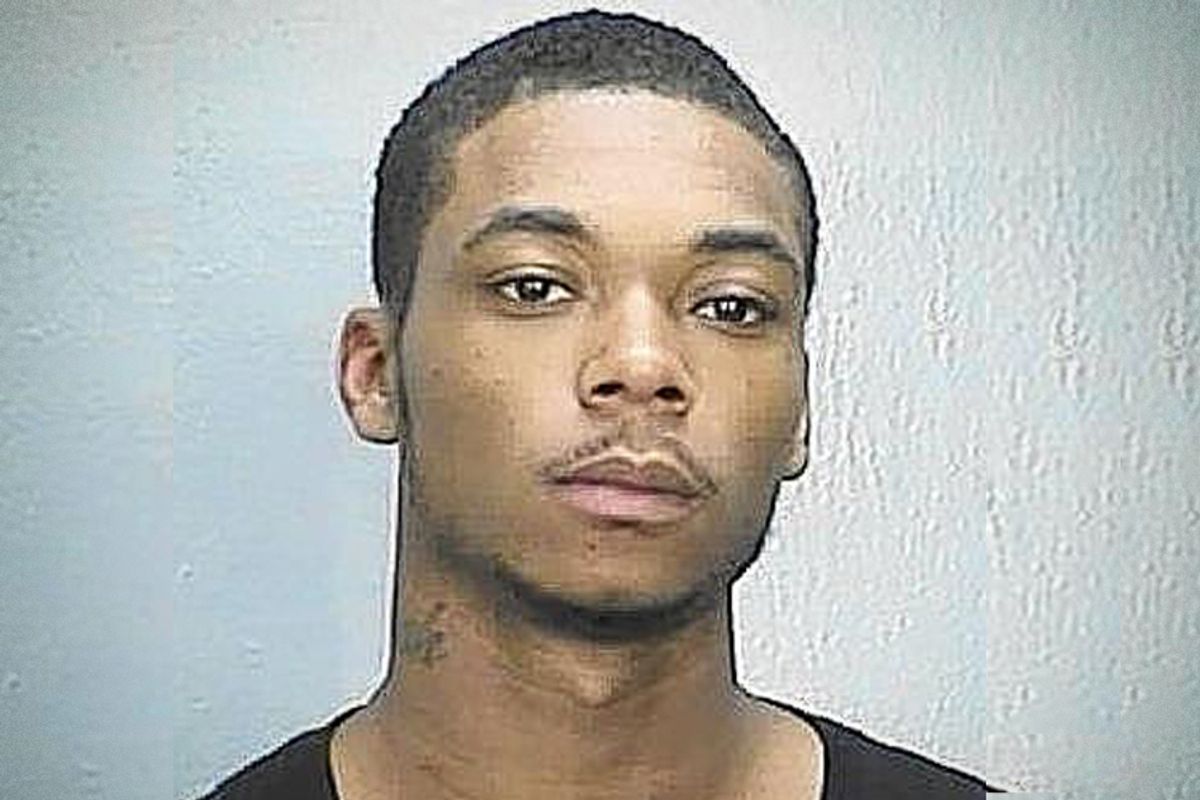

You were scheduled to testify on May 22 in the case of Atwain Steward, aka Twain Gotti, an up-and-coming rapper on trial in Virginia for double murder. The trial received international coverage in large part because you were summoned as an expert. What made the case of Steward so compelling?

Two things: The first is that it highlights a new and disturbing trend in law enforcement. In this case, two people were shot and killed in 2007. The case went cold for four years until an eager new detective started trying to crack it. That’s when he discovered a rap video on YouTube for a song called “Ride Out” by Antwain Steward, aka Twain Gotti, that includes lyrics about murder. Based largely on that video, the police homed in on Steward as a suspect and used it to justify his arrest and then his trial.

Steward’s case is indicative of a new way that horrible police work is often rewarded in the age of social media. Rather than gather actual evidence, police can simply monitor social media for rap lyrics, use the lyrics to charge someone, and watch as the prosecutor secures a conviction with that “evidence.” The head of the Newport News gang unit recently told a reporter that his officers spend roughly half of their time on the computer, often monitoring social media for “clues,” rather than working on the street. That’s crazy, but from the police perspective, that’s a job well done — minimal effort, maximum return. The problem is that it’s totally unjust.

Another issue is Steward’s status as a musician. We’ve found that, generally speaking, well-known rappers like Snoop Dogg, Beanie Sigel or Lil Boosie are less likely to be convicted based upon their lyrics, probably because they have name recognition as artists and, frankly, they have the resources to hire a good defense team. Amateurs, on the other hand, fare much less well. Steward straddles the fence. Just before he was arrested, he signed with a management company and was scheduled to go on a 22-city tour across the country. He’s not nationally known yet, but he’s much farther along than the 16-year-old kid rhyming over borrowed beats in his bedroom.

Were the specific lyrics expected to be used against him particularly compelling evidence?

I watched the interrogation videos with Mr. Steward after his arrest, and the detective kept talking about the song “Ride Out,” at one point saying that the lyrics described the murder “to a T.” Prosecutors also focused on it in a preliminary hearing. These are the lyrics they focused on:

Listen, walked to your boy and I approached him.

12 midnight on his trap house porch and

Everybody saw when I motherfuckin’ choked him.

But nobody saw when I motherfuckin’ smoked him,

Roped him, sharpened up the shank then I poked him.

.357 Smith & Wesson beam scoped him, roped him.

The police were calling this a confession to the 2007 double murder, which is kind of unbelievable. Apart from the fact that the time of day, caliber of gun and number of victims in the lyrics don’t match the actual crime — and that no victim is named at all — I would like to simply point how absurd the lyric actually is. If I’ve got this right, this is a “confession” to a murder that involves a choking, then a shooting, then a “roping” (presumably another kind of choking?), then a stabbing with a shank he sharpens on site, then another shooting, and then a final roping for good measure.

No hyperbole here, right?

So, you were not called to testify in the Steward case but ultimately no rap lyrics were used as evidence at all. What is the theory behind the prosecution’s last-minute decision?

Well, I did notice that prosecutors found opportunities to refer to Mr. Steward as “Twain Gotti” during the trial. That was their way of using rap against him without actually going into detail.

But right, I was literally sitting in a Newport News hotel, waiting for the call to testify that never came. The defense attorney, James Ellenson, finally called at the end of the day and said, “You scared them off!” He thinks that after prosecutors read my preliminary report, which was filed with the court, they didn’t want to deal with my testimony, so they changed their approach to the case, closing off all discussion of rap.

Everyone was shocked. It was a big risk on their part, especially given the impact that violent rap music and videos can have as evidence. In the end, I am thrilled that the case did not end up putting rap on trial, but I will be honest that I was looking forward to testifying.

Can we assume that your role as expert witness in such cases is not over?

No, it has really just begun. I’ve got two more trials lined up for this year, and as I said before, I’d like to work with other scholars so that they, too, can start testifying. The preparation is exhausting, and I can only do so many myself.

When you do testify, what is your role in such cases?

If the lyrics [are accepted as evidence], then my role is to testify in court to provide context for the lyrics, as well as a broader understanding of hip-hop generally. The narrative surrounding rap, both in courts and in the media, is often that it promotes or perpetuates violence, but the history of hip-hop generally, and rap specifically, reveal the exact opposite. Hip-hop was actually conceived by early pioneers like Afrika Bambaataa as a way to end gang violence.

How did your fascination with hip-hop begin?

It began the second I heard it for the first time. I think it was in elementary school playing soccer, when somebody on the sidelines started playing Run DMC from a boom box. I loved it. From there, I started listening to whatever I could — and as a white kid from rural Massachusetts, I naturally gravitated to gangsta rap.

At that age, I didn’t fully understand or try to intellectualize what I was listening to. I’ve always been drawn to lyrical creativity and wordplay, and I think that — combined with the oppositional nature of the music itself (even when it was, in a way, opposing me) — hooked me. I don’t deny that I was also drawn to the tales of violence and lyrics that were even raunchier than what I heard from the older kids on the bus. I was a kid.

But from there, I really started listening to all kinds of rap music, going to whatever concerts I could, and becoming immersed in it. I saw genius in it—and it had a visceral impact as well—and that was that.

Are people often surprised to learn that you -- a suburban-raised white guy nearing middle-age -- are a nationally recognized authority on rap?

I appreciate the generosity, but at 38, I don’t think I can say I’m “nearing” middle age anymore. I’m there. And yeah, people are surprised all the time. When I teach my rap music class, I occasionally see students walk in on the first day, look at me, then check their schedules to make sure they’re in the right room.

That surprise has always been there, really. When I was 16 and going to rap concerts, I’d be one of just a few white people there. And people would come up to me all the time and say, “What are you doing here?” But you know what — it was never in a “get the hell out of here” way. It was genuine surprise that a white kid, obviously not from the ‘hood, would come out to the middle of New Haven or Springfield to listen to Ice Cube or Scarface. Back then — in the early 1990s — if you wanted to see many of these rappers, as a white person you had to be the one who felt out of place. Maybe uncomfortable. That’s not really true anymore, but it was then, and I was always made to feel welcome once I was willing to put myself in that position. It probably didn’t hurt that I knew the lyrics as well, if not better, than most people in the room!

How do your kids feel about it?

My kids are 7 and 5, and they love music generally. They know I write about and teach rap, and I think they are now beginning to see that as cool.

Shares