On Monday, the White House announced a new executive order that will bar federal contractors from discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. This order culminates years of advocacy from those on the front lines of the gay rights struggle to get this president to use the force of his office to reduce discriminatory conditions and processes for LGBTQ people. It is also clear that this administrative shift is part of his very explicit attempt to begin crafting his legacy as the outgoing president.

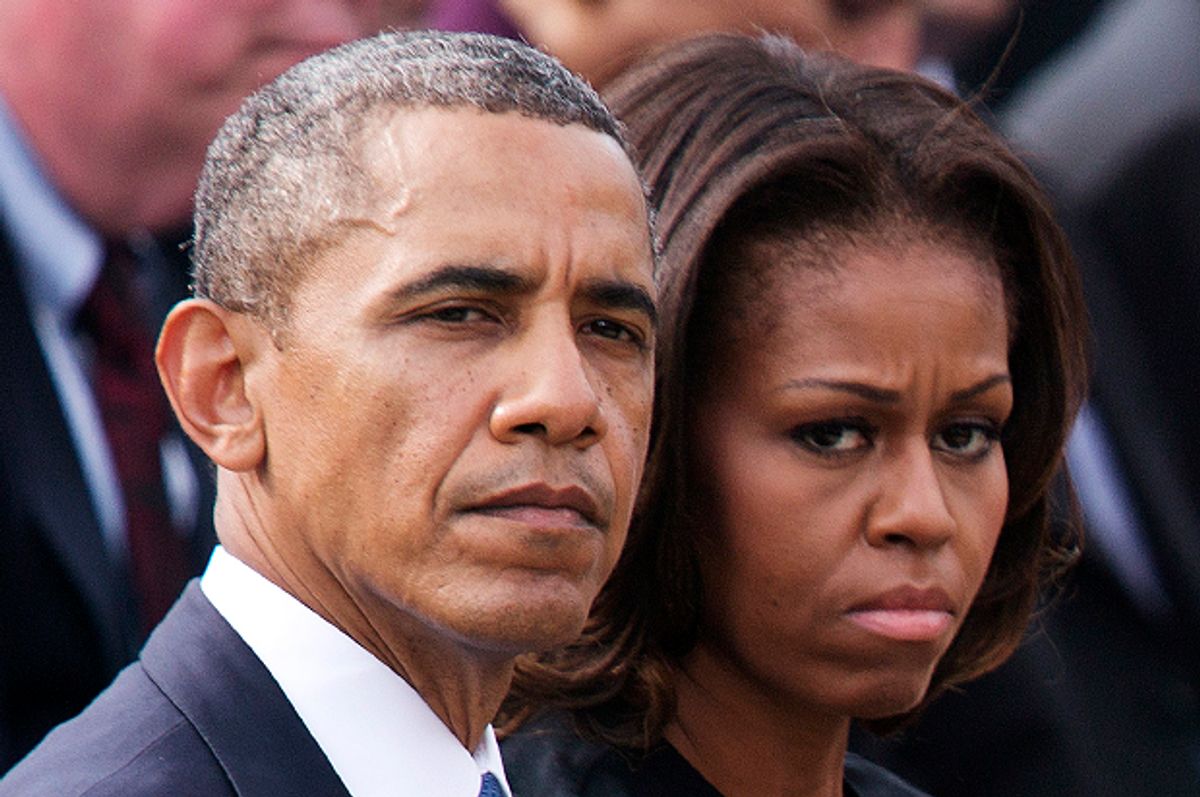

Alongside the Affordable Care Act, My Brother’s Keeper and federal support for robust immigration reform, President Obama continues to roll out a set of initiatives that firmly appeal to the demographics most responsible for his ascent to the White House. Even though I celebrate this signal move on behalf of the Obama administration and urge that the U.S. Congress follow suit and pass federal legislation outlawing discrimination against LGBTQ people, I remain unclear about how to judge the legacy that Obama is building with respect to solidly liberal issues.

Recent advocacy through initiatives like My Brother’s Keeper, expanded clemency opportunities for low-level drug offenders and raising the federal minimum wage suggest explicit attention to the plight of working-class people and men and boys of color. There are also guidelines within the rollout of My Brother’s Keeper to address the especial concerns of gay and trans men and boys of color.

However, there seems to be very little on the horizon for one key demographic: black women and girls. Though the administration could stand to address all women and girls of color, the call earlier this spring for his administration to review its own deportation policies could at least minimally and explicitly begin to ameliorate some of the devastation to Latino families caused by the inordinate amount of deportations presided over by this administration.

However, black women, Obama’s single largest voting demographic, have been the subject of no executive orders, no White House initiatives and no pieces of progressive legislation. Ninety-six percent of black women voters voted for Obama compared to 87 percent of black men. Seventy-six percent of Latinas voted for the president compared to 65 percent of Latino men.

Though black and other women of color who are a part of the LGBTQ community will benefit from this latest executive order, no initiative has explicitly addressed the structural issues of racism, classism, poor education, heavy policing and sexual and domestic violence that disproportionately affect black and Latina women.

As a black woman who voted twice for this president, despite some misgivings, I find myself wondering how we will fit into the legacy of progressive policy initiatives that the president is trying to craft as part of his exit strategy.

This kind of conflict seems to be representative of the political moment in which we find ourselves. I remember feeling conflicted in this way when the Supreme Court struck down DOMA (the so-called Defense of Marriage Act) in the same cycle that it gutted the enforcement of the Voting Rights Act. But with the Supreme Court’s unrepentant band of rabid conservatives, I’m not surprised.

I am surprised, however, that a man who lives in the White House with four black women feels no allegiance at the level of policy or legacy to the one demographic that is most singularly responsible for his two terms in the White House. I am both disappointed and disgusted that in President Obama’s political vision, all the blacks are men.

Twenty five years ago, UCLA law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term "intersectionality" as a way to help us think about how black women were uniquely disadvantaged by employment discrimination laws that could remedy discrimination against women or discrimination against black people, but could not remedy discrimination against black women as an intersecting category. For instance, if a company singled out black women, but not all women, or not all blacks, then black women were simply out of luck in terms of having legal protection. Getting at this concept has been so critically important because anti-workplace discrimination laws have been the centerpiece in terms of how the U.S. has historically counteracted the effects of racism, sexism and homophobia against marginalized groups.

Crenshaw’s coining of that term has also revolutionized the modern academy by helping us to think in almost every humanities and social science discipline about the interactions of race and gender and systems of racism and sexism. These kinds of intersectional interactions help shape the framing of everything from the POTUS discussion of the new restrictions on carbon emissions as a policy that helps poor black and brown youth to the political justifications for the My Brother’s Keeper initiative.

In this way a framework named and articulated by black women to speak to the structural dislocation of black and brown women is now being used to justify our erasure at the policy level.

This is unacceptable.

While I appreciate the carrots that the president continues to throw out to his liberal base, it is clear that black women on the whole are being overlooked and actively dismissed by this administration. I say this, not in an attempt to set racial concerns at odds with LGBTQ issues. LGBTQ people are black and brown, too. But robust attention to discrimination against queer-identified people does not constitute a racial justice program.

And a program that focuses only on boys and men of color does active harm and injustice to black and brown women and girls. If President Obama wants his political legacy to be that he cared the least about the demographic that supported him the most, it should be clear that black women are not going to lie down and take it.

If our votes count, that means our issues ought to count, too. And this is why today, more than 1,000 women and girls of color, including me, have signed a letter urging the president to include women and girls of color in all forthcoming My Brother’s Keeper initiatives.

When it comes to addressing racial justice issues, President Obama’s personal identifications with blackness take center stage, trumping substantial attention to black women as a political constituency. I used to believe that Obama’s personal racial identifications were powerful, that having a president who had experienced racism personally would help him commit to doing something about it when he had the opportunity to do so. But what has become apparent is that President Obama’s personal understanding of racism is deeply tethered to his position as both black and male. The effect is that his personal experience has limited his vision of racial justice to just one gender.

On issues of immigration and LGBTQ rights, the president has to think through the policy and electoral implications of meeting the needs of these constituencies. But on racial justice, the president allows his personal narrative of father-lack to lead. By lamenting the absence of fathers in black families, he unwittingly indicts black mothers, and reinstantiates a patriarchal frame as the thing that will save black communities from ruin. He sounds the alarming ring tones of Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s tangle of pathology thesis, while missing the irony that his lack of father did not prevent him from ascending to the presidency. But then maybe we are supposed to conclude from this that only having a white family can ameliorate the effects of not having a black father.

Such thinking is not only offensive, but pernicious. And as a matter of political resources and policy prescriptions, it’s downright dangerous. Though the president surely knows and relies upon the love, labor and loyalty of black women to help him be great, he engages in political rhetoric that relegates us to an ancillary position, puts us on the defensive, and places us in a politically disadvantageous position. The evidence is on our side, that racism and sexism (alongside poverty and homophobia) severely constrict black women’s opportunities, in everything from education to housing to personal safety. But these facts are no match for the more powerful narrative of the singularity of black male victimization.

The president has shown a willingness in this second term to engage explicitly with structural forces that disadvantage gay and trans people, working-class people, and some subsets of communities of color. For that he is to be applauded. But as he moves down this path, he should remember that it is black women who have worked diligently to clear away the weeds and the brush, and it is we who should not be left stranded by the wayside.

Shares