This week was a huge one for technology at the Supreme Court. The Court issued three opinions — Riley v. California, United States v. Wurie, and American Broadcasting Companies, Inc. v. Aereo — that taken together served as an endorsement of cell phone privacy and a condemnation of the online retransmission of TV shows to paid subscribers.

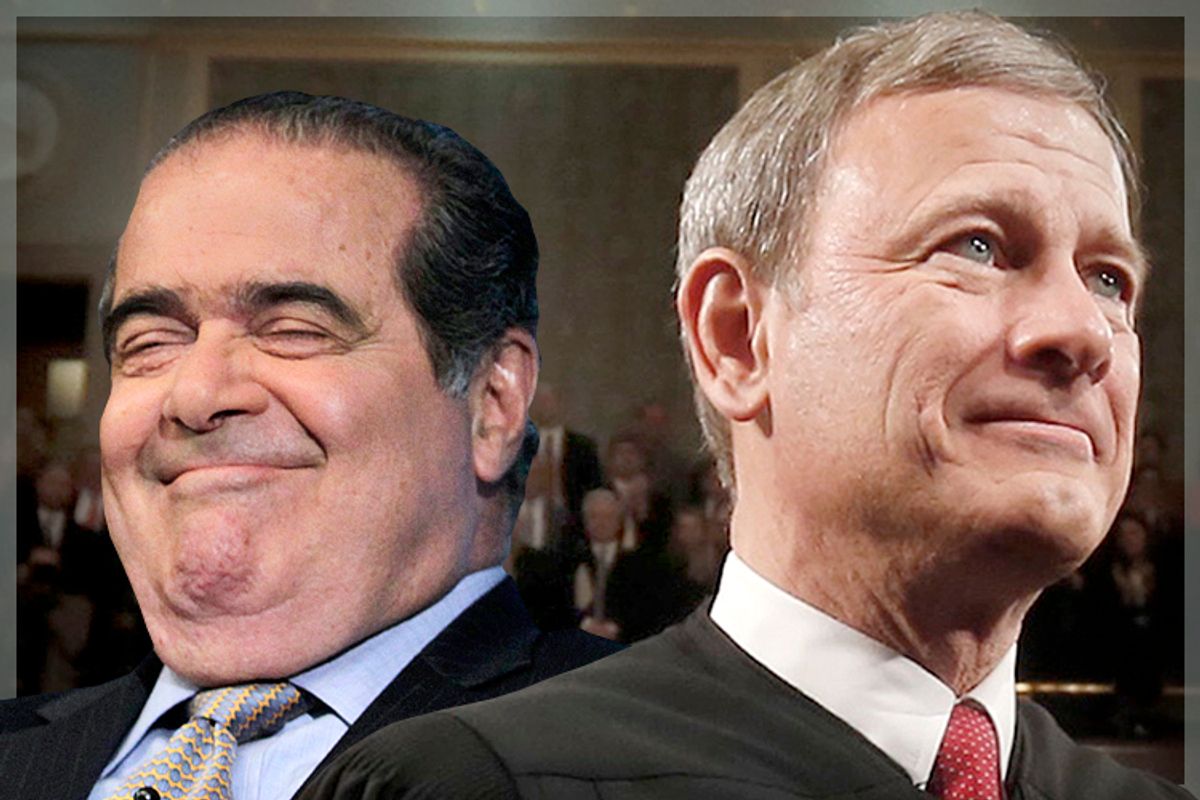

The months leading up to the decisions had been a rough ride for the justices. Following oral arguments for these cases, they were called “black-robed techno-fogeys.” They were ranked based on technological incompetence. Their discussions of “the cloud” became the soundtrack for a comical YouTube video, and the blogosphere cringed when Chief Justice John Roberts learned, for the first time, that some people carry more than one cell phone. So, was all that nervous taunting warranted?

Well, yes, but not for the reasons we thought.

The problem isn’t that the justices are old fogeys. The problem is that the justices were groomed in a field that emphasizes reasoning by analogy. And analogies were critical in these cases: The Aereo decision, for example, hinged on whether the company was more like an equipment provider or a cable company; the Riley and Wurie decisions addressed whether cell phones are sufficiently analogous to wallets. But emerging technology is, by definition, about breaking away from history. Perhaps reason by analogy hamstrings innovation, or perhaps it promotes impartial decision-making. In any event, it helps explain why the justices sometimes say such silly things.

Years of tortured analogies at oral arguments culminated most recently with this week's cases, but a look back at decisions from years past reveals an abundance of strained analogizing. In past arguments, computers were analogized to typewriters, phone books and calculators. Video games were compared to films, comic books and Grimm’s fairy tales. Text messages were analogized to letters to the editor. A risk-hedging method was compared to horse-training and the alphabet. EBay was likened to a Ferris wheel, and also to the process of introducing a baker to a grocer. The list goes on.

“I think there are very, very few things that you cannot find an analogue to in pre-digital age searches,” Justice Breyer said during the Riley oral argument. “And the problem in almost all instances is quantity and how far afield you’re likely to be going.” For the high court, a prior century or two apparently isn’t too far afield.

The justices are tickled by these analogies. Justice Kennedy, for example, appears blissfully unaware of the new definition of “troll,” and covered for his ignorance with a joke during oral argument for eBay v. MercExchange: “Is the troll the scary thing under the bridge, or is it a fishing technique?” This raised eyebrows in the patent industry, where “patent troll” is a stock phrase. Justice Breyer, during the the Riley oral argument, interrupted a discussion about the GPS capabilities of smartphones with another analogy joke: “I don’t want to admit it, but my wife might put a little note [with directions] in my pocket.” (Is the smartphone supposed to be like his wife? Unclear.)

Justice Alito, arguably the most analogy-obsessed of the bunch, best summed up the Court's historical handicap when he teased Scalia in 2011, saying: “I think what Justice Scalia wants to know is what James Madison thought about video games. Did he enjoy them?”

But this fixation on technological analogies is more than just an idle curiosity. It has real-world implications that are not to be underestimated. Recent years have borne out that if a technology under scrutiny cannot be analogized to a historically protected invention, it may be doomed. In 2006, for example, Chief Justice Roberts doubted that eBay was an actual invention. He asked the lawyer, Seth Waxman, what the invention of eBay was, and when Waxman explained it as an electronic market, Chief Justice Roberts responded flippantly, saying, “I mean, it's not like he invented the internal combustion engine or anything. It's very vague.”

When Waxman pushed back at Roberts, pointing out that "I'm not a software developer and I have reason to believe that neither is Your Honor,” Roberts fully explicated his contempt for the technology. “I may not be a software developer, but as I read the invention [of eBay], it’s displaying pictures of your wares on a computer network and, you know, picking which ones you want and buying them.” He next said about the multibillion-dollar Internet corporation: “I might have been able to do that.”

This came from the man who four years later asked the difference between a pager and an email.

So what should a lawyer do to prove an invention is truly an invention if there’s no good historical analogy? Complicate things. In a recent oral argument about a computer-implemented, electronic escrow service, Justice Kennedy asked whether “a second-year college class in engineering” or “any computer group of people sitting around a coffee shop in Silicon Valley” could write the code for it “over a weekend.” The lawyer said yes, to the dismay of many in the industry. No one directly challenged this point, but Justice Roberts referred to a flowchart in one of the briefs: “Just looking at it, it looks pretty complicated. There are a lot of arrows.”

Granted, the justices are behind the times. Twenty-first century technology has come to the Court, but the Court hasn’t come to the twenty-first century. Justices still communicate by handwritten notes instead of email. The courthouse got its first photocopying machine in 1969, six decades after the machine was invented. Oral arguments were first tape-recorded in 1955, nearly a hundred years after the first sound recording. At those arguments, blog reporters are denied press passes, tweeting is verboten, and justices thumb through hard copies of court documents. At the Supreme Court, every day is Throwback Thursday.

This might explain why the majority of Americans oppose life tenure for Supreme Court justices. Life tenure shields judicial independence and pays homage to the Founding Fathers’ vision. At the time the Constitution was written, however, the average life expectancy was about 40 years. (Or 60 years if controlled for infant mortality.) Today, it’s nearly twice as long. Clearly, life tenure meant something different for the founding generation.

Retirement has changed too. The average retirement age for the first 10 justices was 60, but since 1960 has been 75. Four of the nine current justices have passed that 75-year mark with no stated intent to leave. As this Court becomes older than any before it, some worry about mental decrepitude on the bench. Oral arguments, however, indicate no clear correlation between age and understanding technology.

I informally analyzed oral arguments for 10 recent technology cases, sorting the justices’ questions into those that showed confusion and those that showed competence. Over half the time when Justice Scalia asks a tech-related question at oral argument, it is a question that indicates confusion. Justice Kennedy is a close second for most confused. Justice Alito asks about “predigital era” analogues more than any other justice. Justices Ginsburg and Scalia are uncharacteristically quiet in these cases, and Justices Roberts and Kennedy become more vocal. Justice Sotomayor mostly asks questions to show the other justices what she already knows about technology.

The justices can be roughly divided into two age groups: the 75-and-above justices (Ginsburg, Scalia, Kennedy and Breyer), and the 65-and-below justices (Thomas, Alito, Sotomayor, Roberts and Kagan). Justice Breyer is tech-savvy, Justice Alito is not. Justice Kagan is quiet, Justice Kennedy is not. The sample size is small, but the result is clear: When it comes to addressing technology, younger justices are not necessarily better. Instead, the flubs arise where analogies appear.

Before he joined the Court, Chief Justice Roberts suggested that “[s]etting a term of, say, fifteen years would ensure that federal judges would not lose all touch with reality through decades of ivory tower existence.” Justice Scalia has voiced similar concerns about losing touch on the bench, confessing, “You always wonder whether you’re losing your grip.” But a looser grip on outdated analogies might be just what the Court needs.

Shares