In June, magnificent roses bloom in the Sarajevo valley, from residential gardens on the hillsides down to the river and the city center. Apple-size blossoms bow over the iron railings of the stately Ashkenazi Synagogue; a few blocks across the Miljacka River, thorny rose bushes rise in the courtyard of the 16th-century Baščaršijska Mosque. The flowers struck me, when I visited earlier this month, as a kind of unifying emblem in a city famous for its sometimes-fractious diversity.

Ask anyone here what a Sarajevo Rose is, though, and they will point you not to the park but to the pavement, where you can still see the scattered pockmarks left by mortar bombs during the Siege of Sarajevo. More than 11,000 people were killed during that 44-month battle, which, when it ended in 1996, had become the longest siege of the modern era. During the first two years of fighting, Bosnian Serb militias launched an average of 329 mortars a day at Sarajevo, damaging 97 percent of the city’s building stock. Each mortar that hit the pavement left a cluster of scars that, when filled in with a reddish resin, became known as a Sarajevo Rose.

It’s a double meaning that speaks neatly to the way in which the city’s charms have been tarnished by war, its legacy laced with violence. Like Vedran Smajlović’s violin performance in the charred core of the National Library, or the wooden Olympic Stadium seats repurposed to construct coffins, the rose is a symbol of both triumph and pain.

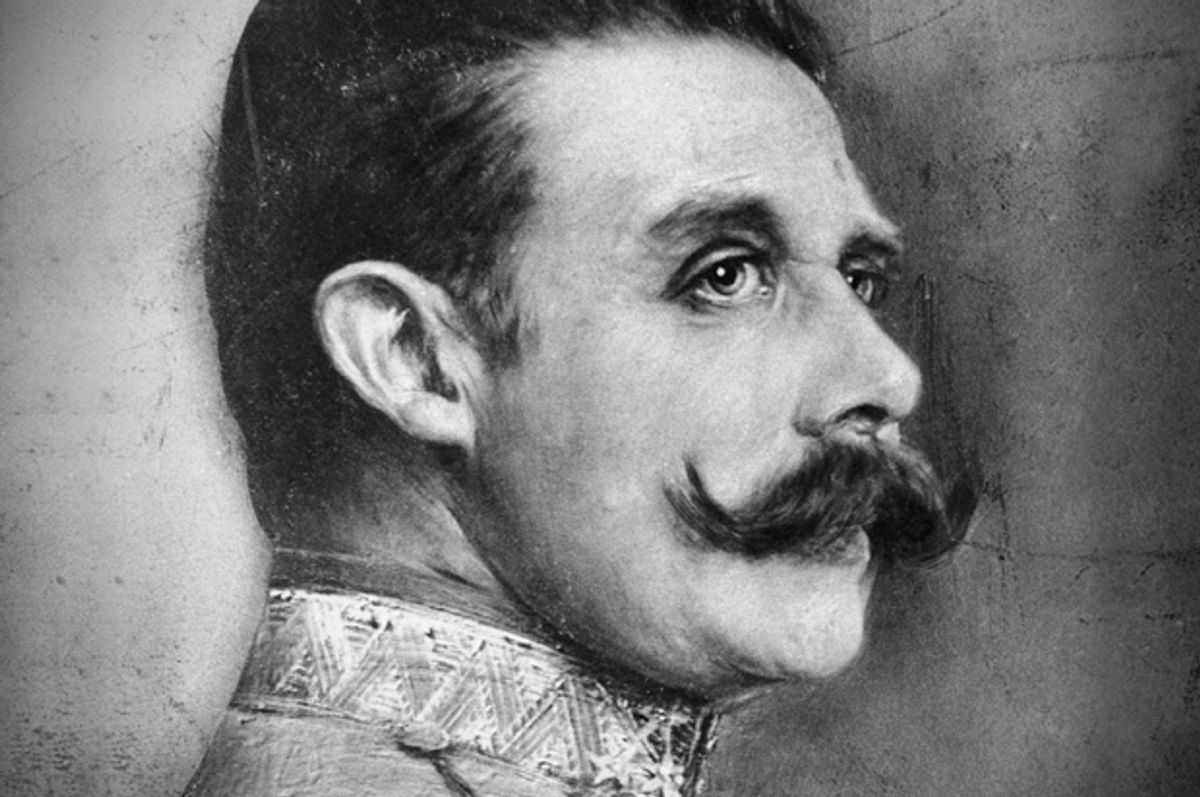

A nearby intersection also harbors a dual symbolism. On this street corner, on June 28, 1914, a 19-year-old Bosnian Serb named Gavrilo Princip assassinated the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sofia, setting in motion a chain of events that led to the First World War.

Today, the adjacent museum labels it “the street corner that started the 20th century.” But that simple historical phrasing is a recent innovation. Over the past century, this unremarkable stretch of sidewalk has hosted a half-dozen memorials, each expressing the contemporary political attitude toward Princip’s deed.

In 1914, this street corner changed history. Since then, it has reflected how history changes.

The fundamental question plaguing this historic site, and one that still paralyzes Bosnia today, is whether Princip and his accomplices were terrorists or heroes. Most of Europe has been firmly of the former mind since 1914, while Serbs in particular have always considered the assassination a noble blow against imperial oppression. This little street has lurched between those interpretations, an urban symbol whose impact has reached not just Bosnians, or Yugoslavians, but global political leaders like Winston Churchill and Adolf Hitler.

The only story that can be told without caveat or argument is the story of the killing itself. Franz Ferdinand, the nephew of the Austrian emperor Franz Joseph I, toured Sarajevo with his pregnant wife on June 28, 1914. The royal couple survived an initial assassination attempt, in the form of a grenade that bounced off their open-top car and exploded behind them. But later, on their way to visit the wounded at the hospital, their car halted in front of Princip, who shot the archduke and his wife at close range with a semi-automatic Belgian pistol.

That sidewalk was put into political service shortly afterward, on June 28, 1917, when the Austro-Hungarian rulers of Bosnia dedicated the Spomenik Umorstvu, or the “Monument to Murder.” In this wartime shrine, a bronze relief of the archduke and his wife was suspended by putti between two 30-foot columns.

The next year, Austria-Hungary fell, Yugoslavia was born, and the monument was dismembered. The medallion now rests in the basement of the nearby Art Gallery.

Yet the new South Slav kingdom -- as Paul Miller, a professor of history at McDaniel College, has shown in a new paper -- was initially reluctant to use the stones of Sarajevo to confront the European consensus. When, in 1930, Yugoslav authorities finally commemorated the incident with a small inscription noting that Princip had “proclaimed freedom,” they immediately faced international opposition from public figures who considered the assassination a despicable casus belli – not a justified act of anti-colonial rebellion. Churchill called the memorial an “infamy,” and the associated outrage convinced Yugoslavia to disown its own dedication ceremony.

The Nazis, however, did not look kindly on even this modest celebration of local nationalism. Just days after they entered Sarajevo in the spring of 1941, Nazi officers removed the tablet and presented it to Adolf Hitler as a 52nd birthday present, a symbolic tribute from a conquered city.

Four years later, power shifted again, pulling this street corner along. The postwar Yugoslav plaque, unveiled at an elaborate state ceremony in May 1945, was dedicated “as a symbol of eternal gratitude to Gavrilo Princip and his comrades, to fighters against the Germanic conquerors.”

The adjacent Latin Bridge was renamed for Princip, and in the coming years, a concrete cast of Princip’s footprints was embedded in the sidewalk, inaugurating one of the world’s more macabre photo ops. Tens of thousands of visitors (see Page 17) posed as Princip, mimicking an act of murder within living memory.

Some Yugoslavs were always uncomfortable with the consecration of the murder, as Miller documents. But Princip’s legacy was contested even among his acolytes. Was he a martyr for a South Slav state, the harmonious vision realized in Tito’s Yugoslavia? Or did he envision the creation of a more ethnically focused Greater Serbia?

"Because there was an ambiguity about what he was fighting for,” says John Paul Newman, a professor of Yugoslav history at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth, “he’s become to some extent a blank slate."

In 1992, as Bosnia descended into a war that essentially pitted Bosnian Serbs against Croats and Bosniaks, both sides came to see Princip as a Serbian symbol — and his corner of central Sarajevo as a symbolic prize. As Bosnian Serbs laid siege to the city, the municipal government restored the “Princip Bridge” to its original name, the Latin Bridge.

The famous cement footprints disappeared soon afterward – but no one can quite say how.

An employee at the neighboring museum told me that they were obliterated by Bosnian Serb explosives, a version of events that has also been reported by Reuters. Fran Markowitz and Anne Marie du Preez Bezrob, in their books about Sarajevo, allege that Serbian nationalists stole the footprints. A third story (recounted by Christopher Hitchens, among others) is that Princip’s footprints fell victim to popular rage, pried from the sidewalk by angry crowds. Finally, it’s possible that the city of Sarajevo made their effacement a municipal priority, a kind of declaration of the new politics of the city.

There is something remarkable about this, that the true fate of this most famous site has so quickly vanished beneath a set of hazy parables. But the facts we forget matter less than the stories we remember. If the history of Princip’s corner is a microcosm of Sarajevo’s own, then perhaps these competing tales – each with its own political implications – compose a fitting account of those chaotic years.

Today, the commemoration comes as close to objectivity as it has in its hundred-year history. A simple plaque installed in 2004 reads, “From this place on 28 June 1914 Gavrilo Princip assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sofia.” There is no mention of the repercussions. A reproduced cast of the famous footprints lurks in the shadows of the museum.

The centenary commemoration this week has been slightly more elaborate, and naturally, more divisive. Even a conference of historians could not rise above the fray. In a gesture of peace, the Vienna Philharmonic plays in Sarajevo on Saturday, the culmination of a two-week series of local events. But the Serbian half of Bosnia has declined to participate, opting for a more celebratory take on Princip’s legacy.

Even without the fraught politics of Princip, the assassination that changed the world is a complex inheritance for Sarajevo. It is a famous mark of violence on a city that is trying to put that reputation behind it. But it is also a reminder, from a troubled and tiny nation that has at times struggled to remind the continent of its existence, that its history is Europe’s own.

Shares