On all 2,636 hours of secretly recorded Nixon White House tapes that the government has declassified to date, you can hear the president of the United States order precisely one break-in. It wasn’t Watergate, but it does expose the roots of the cover-up that ultimately brought down Richard Milhous Nixon. Investigation of its origin reveals almost as much about the president’s rise as his fall.

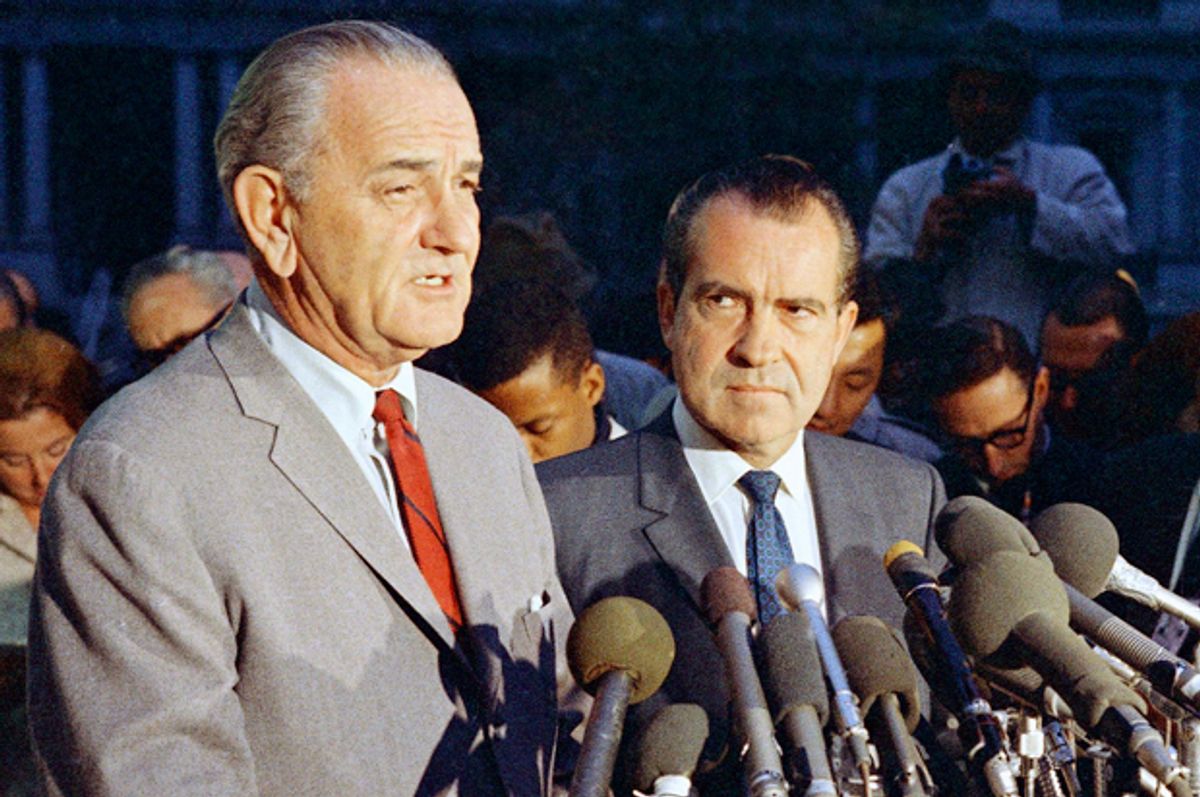

June 17, 1971, 5:15 p.m., the Oval Office. None of the president’s men knew what to do when he ordered them to burglarize the Brookings Institution, a venerable Washington think tank. Richard Nixon had gathered his inner circle to talk about something entirely different—the recent leak of the Pentagon Papers, at that point the biggest unauthorized disclosure of classified information in US history. The seven-thousand-page Defense Department history of Vietnam decision making during the administrations of Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson had nothing on President Nixon. The study stopped well before his election, climaxing with LBJ’s surprise March 31, 1968, announcement that he would not seek a second full term.

In that same speech, Johnson created the issue that nearly sank Nixon’s presidential campaign. LBJ announced that he was limiting American bombing of North Vietnam—and would stop it completely if Hanoi could convince him that this would lead to prompt, productive peace talks. Throughout the fall campaign, Nixon worried that LBJ would announce a bombing halt before Election Day, a move that would boost the Democratic nominee, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey. Johnson did, and it did. The president announced the bombing halt on Halloween, less than a week before the voting. The Republican nominee, who had begun the campaign 16 points ahead in the polls, watched his lead disappear. Nixon still won, but it was too close—at that point the second-closest race of the twentieth century, right behind the one he had lost in 1960 to JFK.

“You could blackmail Johnson on this stuff, and it might be worth doing,” said White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman, a California public relations executive with blue eyes and a brush cut who spent years polishing Walt Disney’s image before taking on the greater challenge of managing Nixon’s.

“How?” the president asked.

“The bombing halt stuff is all in the same file,” Bob Haldeman said. “Huston swears to God there’s a file on it at Brookings.” Haldeman was working with some bad information. Tom Charles Huston, author of the secret Huston Plan to expand government break-ins, wiretaps, and mail opening in the name of fighting domestic terror, claimed Brookings had a top secret report on the bombing halt, written under the direction of some of the same people who oversaw the Pentagon Papers project.

“Bob, now you remember Huston’s plan? Implement it,” the president said.

An aide began to object.

President Nixon: "I mean, I want it implemented on a thievery basis. Goddamn it, get in and get those files. Blow the safe and get it."

This wasn’t what Haldeman had in mind. He wanted government officials to visit Brookings on the pretext of inspecting how it stored classified material and to confiscate the bombing halt file in the process. No one in the Oval Office pointed out that the president’s idea was illegal. National Security Adviser Henry A. Kissinger, a former Harvard government professor with a profound German accent, asked the obvious question: “But what good will it do you, the bombing halt file?”

“To blackmail him,” the president said. “Because he used the bombing halt for political purposes.”

“The bombing halt file would really kill Johnson,” Haldeman said.

“Why, why do you think that?” Kissinger asked.

The timing, Haldeman said. Johnson stopped the bombing less than a week before the election.

“You remember, I used to give you information about it at the time,” Kissinger said, reminding them of the secret role he had played as an informant to the 1968 Nixon campaign on Johnson’s bombing halt negotiations. Kissinger had worked as a consultant on a 1967 bombing halt initiative for LBJ, so when he visited the American negotiating team in Paris during the 1968 talks, members confided in him. He gained Nixon’s trust by betraying theirs. “To the best of my knowledge, there was never any conversation in which they said we’ll hold it until the end of October,” Kissinger said. “I wasn’t in on the discussions here. I just saw the instructions to [Ambassador W. Averell] Harriman.” (Years later, Kissinger denied having had access to information about the negotiations at the time; the instructions to Ambassador Harriman, LBJ’s lead negotiator with the North Vietnamese, were, of course, highly classified information.) If Kissinger was right, then even if Nixon got someone to break into Brookings and steal the bombing halt report, it was unlikely to contain the blackmail information he said he wanted.

Yet Nixon ordered the Brookings burglary at least three more times in the next two weeks. It was one of the reasons he took the fateful step of creating the Special Investigations Unit (SIU), an unconstitutional secret police organization better known as “the Plumbers” because one of its jobs was to plug leaks. The SIU recruited a former FBI agent with experience conducting “black bag jobs” (that is, government-conducted break-ins) and a former CIA agent experienced in covert operations.

Exactly one year to the day after Nixon first ordered the Brookings break-in, a different one planned by these two former government agents took place at Democratic National Committee (DNC) headquarters in Washington’s Watergate apartment and office complex. Once Washington, DC, police arrested five men in dark suits and blue gloves at the DNC offices on the morning of June 17, 1972, President Nixon faced a stark choice. An unobstructed investigation of the crimes the two former government agents had committed would lead back to ones that the president himself had ordered. He could either order a cover-up or face impeachment.

So why did Nixon want the bombing halt file so badly in the first place? What good would blackmailing LBJ do, anyway? (At that point, Nixon just wanted the former president to hold a press conference denouncing the leak of the Pentagon Papers—not much of a motive to commit a felony.) The potential downside was enormous—impeachment, conviction, prison, disgrace—and the upside was questionable at best. If Nixon were the kind of president to conduct criminal fishing expeditions for dirt on his predecessors, his tapes would be littered with break-in orders. But Brookings is the only one.

There is a rational explanation. Nixon did have reason to believe that the bombing halt file contained politically explosive information—not about his predecessor, but about himself. Ordering the Brookings break-in wasn’t a matter of opportunism or poor presidential impulse control. As far as Nixon knew, it was a matter of survival. The reasons why are not on Nixon’s tapes, but on those of his predecessor.

Imitation of the Enemy

The president pounded his desk at his first meeting of July 1, 1971, as he told Haldeman and Kissinger, “We’re up against an enemy. A conspiracy. They’re using any means. We are going to use any means. Is that clear? Did they get the Brookings Institute raided last night? No. Get it done. I want it done. I want the Brookings Institute safe cleaned out.”

In his classic essay on conspiracy theorists, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” the historian Richard Hofstadter wrote, “A fundamental paradox of the paranoid style is the imitation of the enemy.” When Nixon conceived of his enemy as Jews, intellectuals, and Ivy Leaguers who arrogantly placed themselves above the law, he gave himself license to do likewise. He placed himself above the law that prohibits the disclosure of grand jury testimony, for one. “This is a conspiracy. It does involve these people, and they are not on very good ground in many cases. Also, we now have the opportunity really to leak out all these nasty stories that’ll kill these bastards,” he said. Though sworn to preserve the Constitution, he placed himself above the Sixth Amendment guarantee of the right to a fair trial. “Screw the court case,” the president said. “I mean, just let’s convict the son of a bitch in the press. That’s the way it’s done!” These orders don’t make Nixon a cackling villain out of melodrama, glorying in his own malevolence. Imitation of the enemy is a faulty kind of moral reasoning, a trumped- up claim of self- defense. Nixon did unto others as he feared they would do unto him. His conspiracy theory enabled him to claim he was fighting fire with fire. But it turned him into what he hated.

It’s questionable whether what Ellsberg did can accurately be called stealing classified government documents, but that’s a perfectly accurate way to describe what Nixon intended to do as he put together an organization to burglarize a think tank, blow its safe open, and obtain a top secret report. Imitation of the enemy, as Hofstadter wrote, produces “secret organizations set up to combat secret organizations.” To fight an imaginary conspiracy, the president initiated a real, criminal one.

Excerpted from “Chasing Shadows: The Nixon Tapes, the Chennault Affair, and the Origins of Watergate” by Ken Hughes. Copyright © 2014 by Ken Hughes. Reprinted by arrangement with University of Virginia Press. All rights reserved.

Shares