Researchers are out with the first-ever global measurements of marine mercury, putting a number on pollution's impact. It's a big one: Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, they found, surface mercury levels have more than tripled.

The international team spent eight years collecting water samples from the Atlantic, Pacific, Southern and Arctic oceans, measuring mercury concentrations and then figuring out how much of it was put there by humans (gotta love that gold mining and coal burning). Science Magazine reports on their findings:

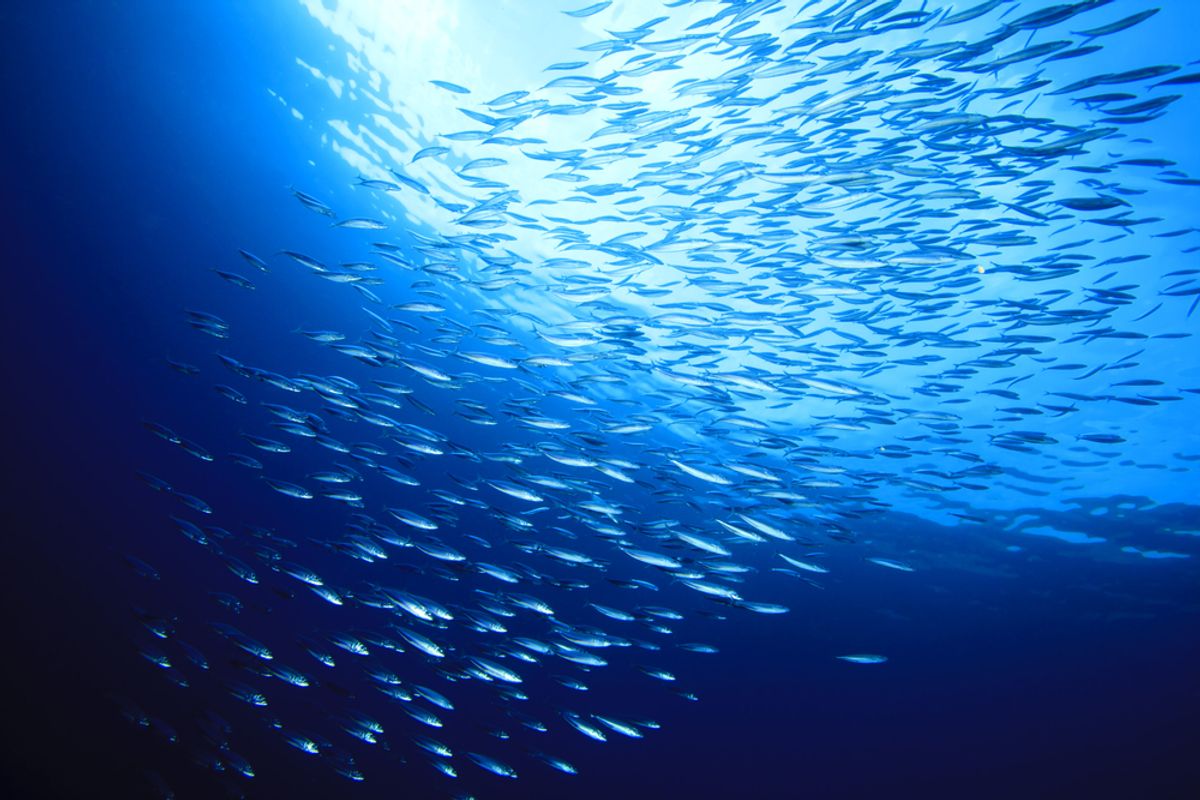

The calculations suggest that the ocean contains about 60,000 to 80,000 tons of mercury from pollution, with almost two-thirds residing in water shallower than a thousand meters, the team reports online today in Nature. Mercury concentration in waters shallower than 100 meters has tripled compared with preindustrial times, they found, whereas mercury levels in intermediate waters have increased by 1.5 times. Higher mercury concentrations in shallower waters could increase the amount of toxin accumulating in food fish, exposing humans to greater risk of mercury poisoning, [Carl Lamborg, a marine geochemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts and one of the study's authors] says. Countries ringing the North Atlantic Ocean, where the mercury concentration is among the highest recorded in the study, may be particularly vulnerable.

The scientists aren't sure how the mercury we put in the ocean transforms into methylmercury, the toxicant that can build up in predator fish like tuna and potentially threaten those of us who eat them. So they're not saying this poses a human health concern -- yet. But Lamborg told Nature that at our current rate, humans are "on track to emit as much mercury in the next 50 years as they did in the last 150."

“I would not stop eating ocean fish as a result of this,” Simon Boxall, lecturer on ocean science at the University of Southampton, told the Guardian. “But it is a good indicator of how much impact we are having on the marine environment. It is an alarm call for the future.”

Shares