The common view of great teachers is that they are born that way. Like Michelle Pfeiffer’s ex-marine in "Dangerous Minds," Edward James Olmos’s Jaime Escalante in "Stand and Deliver," and Robin Williams’s “carpe diem”–intoning whistler in "Dead Poets Society," legendary teachers transform thugs into scholars, illiterates into geniuses, and slackers into bards through brute charisma. Teaching is their calling—not a matter of craft and training, but alchemical inspiration.

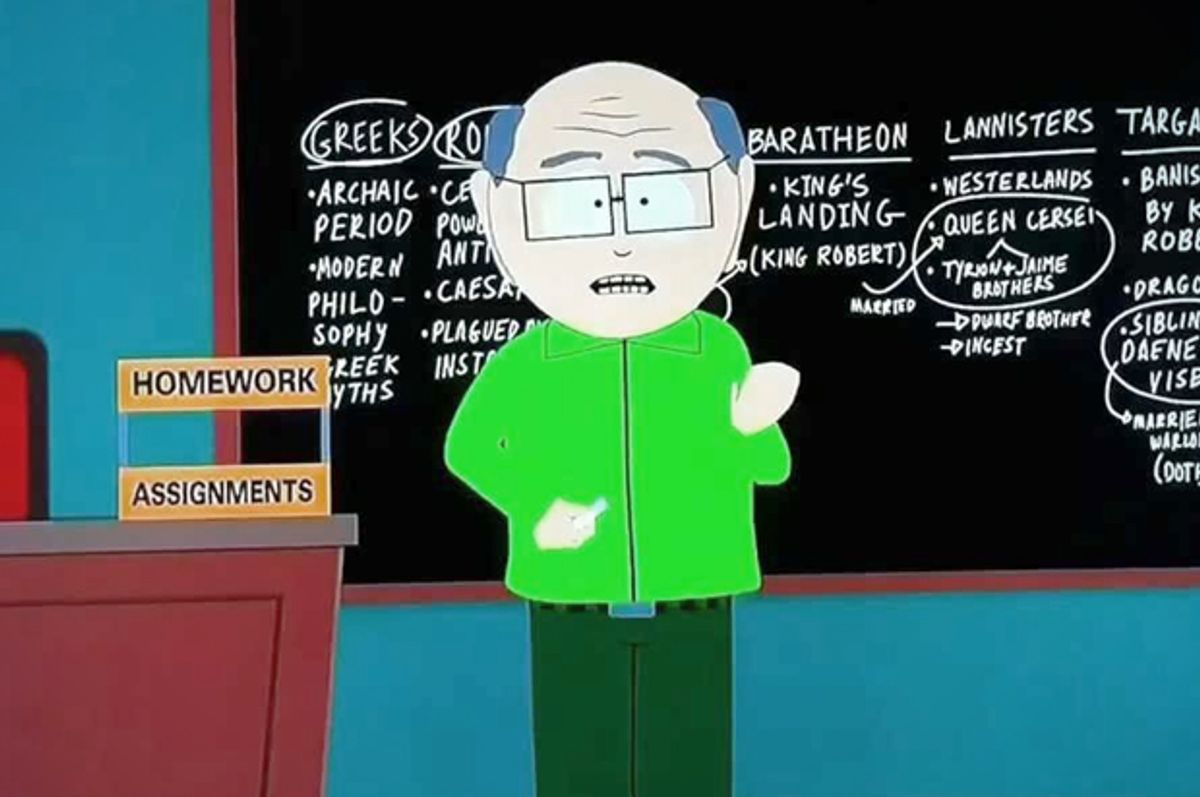

Bad teachers, conversely, are portrayed as deliberately sadistic (as with the Sue Sylvester character on "Glee"), congenitally boring (Ben Stein’s nasal droner in "Ferris Bueller’s Day Off"), or ludicrously dim-witted (Mr. Garrison from "South Park"). These are the tropes of a common narrative, a story I’ve come to call the “Myth of the Natural-Born Teacher.”

Even in the rare cases where fictional teachers appear to improve—as happens in "Goodbye, Mr. Chips," the novel-turned-film, in which a bland schoolteacher named Mr. Chips comes to “sparkle”—the change is an ugly duckling–style unmasking of hidden pizzazz rather than the acquisition of new skill. Others think Mr. Chips has become a “new man,” but in fact, we are told, he has only peeled back a “creeping dry rot of pedagogy” to reveal the “sense of humor” that “he had always had.”

The idea of the natural-born teacher is embedded in thousands of studies conducted over dozens of years. Again and again, researchers have sought to explain great teaching through personality and character traits. The most effective teachers, researchers have guessed, must be more extroverted, agreeable, conscientious, open to new experiences, empathetic, socially adjusted, emotionally sensitive, persevering, humorous, or all of the above. For decades, though, these studies have proved inconclusive. Great teachers can be extroverts or introverts, humorous or serious, flexible or rigid.

Even those charged with training teachers—the ones who, by definition, should believe teaching can be taught—believe the natural-born-teacher narrative. “I think that there is an innate drive or innate ability for teaching,” the dean of the College of Education at Chicago State University, Sylvia Gist, told me when I met with her in 2009. The consensus seems to be, you either have it or you don’t.

Before I met Magdalene Lampert, I ascribed to this view as well. My teacher friends seemed born for the blackboard. I could see it in their personalities and in how much they cared—one’s earnest, unabashed sensitivity; another’s confident, playful devotion. Gregarious, charming, and theatrical, they commanded attention wherever they went. No wonder they decided to teach, while I—shamefully serious, allergic to goofiness, prone to skepticism—became a journalist. They had the magical quality of “teacherness”—what Jane Hannaway, the director of the National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research and a former teacher, described to me as “voodoo.”

When I first met Magdalene, her talent was obvious, and it did, at first, look like voodoo. It was the winter of 2009, twenty years after she taught fifth-grade math to Catherine and Richard, and she was now a professor at the University of Michigan’s School of Education. We sat in her sun-soaked office, at the far end of a long table, looking at the work of a fifth-grader named Brandon.

In the course of solving a problem about the price of party ribbons, Brandon had mistakenly declared that 7∕12 = 1.5. What, Magdalene asked me, could have made him think that?

This was probably the first time Magdalene read my mind, which is what she does after asking a question. She lowers her eyelids slightly, purses her lips, and peers into your soul. I had no idea how Brandon could have come up with 1.5, and she knew it.

But instead of giving me the answer, she wanted me to think about what might make sense (just as, back in 1989, she had wanted Richard to think about his answer, 18). She drew a longdivision sign, that “house” that I remembered from fifth grade. She placed the numbers in the wrong spots: 12 under the house and 7 outside of it, to the left, as if we were asking how many times 7 went into 12 rather than how many times 12 went into 7. Putting 7 into 12, a student would find that it went in once, with a remainder of 5 (12 – 7). “1 R 5,” he would have written, in the language of fifth grade.

When we looked at Brandon’s paper, that is exactly what we saw: a house over 12, with 7 on the outside, and then “1 r 5” written next to it in green marker. Brandon, Magdalene explained, must have mistakenly translated his “1 r 5” into 1.5. (The answer is actually 1 and 5∕7.)

It seemed like a magic trick—how quickly Magdalene moved from noticing a problem to diagnosing its source. Instead of just looking at the final wrong answer, she had translated Brandon’s notes—almost nonsensical to me—into a logical (if flawed) path, skipped backward through his thinking, and located the original point of misfire. It took her no more than a minute.

And what about all the other errors Brandon could have made as he struggled to find the price of those ribbons? What about the mistakes scattered through his classmates’ papers, not to mention all the ones that weren’t there, but could have been? This, after all, was just the work of one class, taken from one day out of the year, in one grade and one subject, by one student. I watched, captivated, as Magdalene worked through more papers, reading backward through the minds of the children, each prone to his own unique mistakes.

But the more I learned about Magdalene and her teaching, the more I saw that what looked like mind reading was in fact the result of extraordinary skill, not inborn talent. Her success did not depend on her personality, which—inward, pensive, and measured—was in many ways the opposite of Hollywood’s mythic teachers. Instead, Magdalene’s success relied on a body of knowledge and skill that she had spent years acquiring. Teaching, as she practiced it, was a complex craft.

Magdalene showed me that the illusion of the natural-born teacher is at best a polite version of the old adage attributed to George Bernard Shaw: “He who can, does. He who cannot, teaches.” By imagining teaching as a “voodoo” mixture of personal charisma and passion, we are saying, essentially, He who has intelligence, does. He who has charm, teaches. I have come to think that this is a dangerous notion. By misunderstanding how teaching works, we misunderstand what it will take to make it better—ensuring that, far too often, teaching doesn’t work at all.

*

“Aha!” Magdalene Lampert’s decision not to correct Richard had paid off—partly, anyway.

His nonsensical answer, that the car traveling at a speed of 55 miles per hour would go 18 miles in 15 minutes, remained on the board. But after Magdalene asked the class whether anyone agreed with his answer, enduring an uncomfortable pause when nobody said anything, Richard finally broke the silence.

“Can I change my mind?” he asked her. Instead of 18, he wanted to “put thirteen and a half or thirteen point five.”

Better! The calculation he should have made is that, since 55 miles corresponds to 60 minutes, and half of 55 miles, 27.5, corresponds to 30 minutes, then a quarter of 60 minutes would be half again: 13.75. He was close.

But Magdalene still didn’t understand why he’d first said 18. She needed to know exactly what had gone wrong inside his head. Pointing to the place on the chalkboard where Richard had originally written “18,” she asked him why he’d changed his mind.

He was back in his seat. “Because,” he said, “eighteen plus eighteen isn’t twenty-seven.”

“Aha!” she said, permitting herself a minor celebration.

He had it—at least, most of it. Keeping her hand on the board so that it covered up the old wrong answer, 18, Magdalene pivoted so that her body faced Richard and the rest of the class. She wanted everyone to hear what she had to say. Richard had gone from stumbling to coming up with the beginnings of a proof—a mathematical argument for why 18 couldn’t be the answer—and she wanted to draw everyone else’s attention to his work.

In the back of the room, students started murmuring. “Not close!” one shouted out. Another student threw up his hand.

Magdalene took note but did not make a move just yet. She thought about 27. The board, of course, said the correct number of miles that is half of 55—27.5, not 27. If he had been shooting for precision, Richard would have tried to find a number that, when doubled, equaled 27.5, not 27. But if they were talking about a real car, making a real trip, would it matter if he calculated a distance of 13.5 miles, rather than 13.75? It might, and it also might not. Still, learning to make approximations was an important skill, and Magdalene was happy with Richard’s performance. He was estimating—proving, even—thinking mathematically.

She did not want to make Richard think he’d made a mistake, but she also wanted to help him and the rest of the class reach the exact answer. After all, if she hadn’t wanted the students to deal with the tricky matter of having to divide 27.5 into two pieces, she could have picked a rounder speed, like 60 miles an hour. Then the math would have been nice and clean. But one of her objectives for the year was to have students learn to convert between decimals and fractions, and to divide each of them in their heads. She had picked 55 because she wanted the class to struggle with exactly this problem, in exactly this way.

How to acknowledge Richard’s good work but also, at the same time, correct it? She surveyed the growing field of raised hands. Anthony, a small boy whom Magdalene knew loved to talk, was waving his hand in the air. Awad, a quiet boy with neat, curlicue handwriting, had his hand up too. Who would keep up her ambiguous tone: accepting Richard’s answer, but expanding on it? She chose Awad.

*

Paradoxically, the institution most susceptible to the fallacy of the natural-born teacher is our country’s public school system. And that’s despite the fact that alarm—always high—over the disappointing level of our national teaching quality has recently reached a fever pitch.

“From the moment our children step into a classroom,” Barack Obama said in 2007, “the single most important factor determining their achievement is not the color of their skin or where they come from; it’s not who their parents are or how much money they have. It’s who their teacher is.” Obama was then a presidential candidate; in office, his position only strengthened. Today, thanks to policies that his administration has advanced, school districts across the country are undergoing ambitious efforts to reinvigorate their teaching force. The debate about these reforms is fierce; many people, including many teachers, oppose Obama’s efforts. But their objection is not usually with his premise. They agree that teachers matter and that the quality of their work should be improved. What they dispute is how to enact the change.

One argument—Obama’s—prescribes improvement by way of accountability. The problem with American education, this line of thinking goes, is that we have for too long treated all teachers the same: they get the same pay raises, the same evaluations, and the same job protections whether they inspire their students like Robin Williams or stultify them like Ben Stein. But the fact is that some teachers are good and some are bad. Some help children learn while others set them back.

“They have 300,000 teachers in California,” Obama explained in a speech in 2009. “The top 10 percent are 30,000 of the best that are out there. The bottom 10 percent are 30,000 of the worst out there. The problem is, we have no way to tell which is which.” This, he went on, “is where data comes in.” By measuring which teachers are successful and which aren’t, we can reward the phenoms and discard the duds, thereby improving the overall quality of the teaching force. Following Obama’s prescription, revamped teacher evaluation systems are now being rolled out across the country, along with rewards and punishments that will affect teachers’ careers.

The other argument—call it the autonomy thesis—prescribes exactly the opposite. Where accountability proponents call for extensive student testing and frequent on-the-job evaluations, autonomy supporters say that teachers are professionals and should be treated accordingly. Like lawyers or doctors, they will improve only if they are given the trust, respect, and freedom they need to do their jobs well. Lately, proponents of this argument have been drawing comparisons to Finland. There, a recent report by the Chicago Teachers Union described, “teaching is a respected, top career choice; teachers have autonomy in their classrooms, work collectively to develop the school curriculum, and participate in shared governance of the school.” In Finland, the report concludes, teachers “are not rated; they are trusted.”

As descriptions, both arguments—accountability and autonomy—contain a measure of truth. Teachers do lack some of the freedom they need to teach well, and they also lack adequate feedback. But as prescriptions, actual suggestions for how to improve teaching, the arguments fail. Neither change, on its own, will produce better teachers. Basic math makes the problem with accountability clear: Discard the bottom 10 percent and, as Obama said, that’s thirty thousand teachers who will need to be replaced. And that’s just in California. Nationally, the number is more than ten times that. Autonomy, meanwhile, is an experiment that many schools have tried for years, and still seen teachers struggle.

Neither accountability nor autonomy is enough, in other words, because both arguments subscribe to the myth of the natural-born teacher. In both cases, the assumption is that good teachers know what to do to help their students learn. These good teachers should either be allowed to do their jobs or be held accountable for not doing them, and they will perform better.

Both arguments, finally, rest on a feeble bet: that the average teacher will figure out how to become an expert teacher—alone. This bet is especially audacious, considering the large number of people involved. More people teach in this country than work at McDonald’s, Wal-Mart, and the U.S. Post Office combined. In New York City, where I live, a corps of teachers seventy-five thousand strong makes up a workforce roughly the same size as Apple’s global employee base. As Amy McIntosh, the former chief talent officer of New York City’s Department of Education, pointed out, in all the five boroughs there is no building where all seventy-five thousand teachers could gather at a single time. Not even Yankee Stadium (capacity 50,287).

Of the fields to which teaching is commonly compared—those that require a college degree and are considered of reasonably high social value—none come close to matching the number of employees that teaching has. Consider a bar graph displaying the number of Americans in different professions. The shortest bar represents architects: 180,000. Farther over, slightly higher, come psychologists (185,000) and then lawyers (952,000), followed by engineers (1.3 million) and waiters (1.8 million). At the top stand the big three: janitors, maids, and household cleaners (3.3 million); secretaries (3.6 million); and, finally, teachers (3.7 million). An ongoing swell of baby boomer retirements is expected to force school systems to hire more than three million new teachers between 2014 and 2020. As the departing teachers wave goodbye to their students, they will take all their experience and skill out the door with them. These new hires will have to replace them.

One December night in 2009, I watched as hundreds of the people hoping to become teachers packed an auditorium at Chicago’s Cultural Center, home of the world’s largest stained-glass Tiffany dome, to hear from the city school system’s director of recruitment. There were no seats available, and the sea of humanity was as diverse as it was vast. There was a cross-eyed woman with white hair and a disheveled look. There was a dreadlocked recent college graduate with hair dangling below his belt. There were many dozens of young midwestern ladies with their mothers, taking careful notes. There was a small woman in a Christmas sweater with ornaments sewn into quadrants, including a Velcro nameplate stuck on her left breast: RACHEL.

But even if everyone in the auditorium had signed up to teach—the mothers along with their daughters—the crowd still would not have filled all the available teaching slots. Each year, the city of Chicago hires two thousand new teachers. That year, the economic downturn had lowered the number below its average. But the district still needed six hundred new teachers. Nationwide, nearly four hundred thousand new teachers start work at public and private schools every year.

When all these people take their place in front of classrooms across the country—from the overcrowded trailers in Queens, New York, to the humid, ranch-style spaces serving Alabama Native American reservations, to the breezy, open-air classrooms of Cerritos, California—what will they do? What should they do? And how can we make sure all of them do the best possible job?

The cold truth is that accountability and autonomy, the two dominant philosophies for teacher improvement, have left us with no real plan. Autonomy lets teachers succeed or fail on their own terms, with little guidance. Accountability tells them only whether they have succeeded, not what to do to improve. Instead of helping, both prescriptions preserve a long-standing culture of abandonment. Steven Farr of Teach For America described this culture by telling me about the first time his assigned mentor came to observe his class. The mentor was just doing her job, but when she walked in, she apologized, as if for some voyeuristic intrusion. Teaching, she told him, is “the second-most private act.” She’d rather not be caught watching someone else do it.

The sociologist Dan Lortie, in his classic work Schoolteacher, describes the teaching profession in the language of Victorian-era sex: a private “ordeal.” Lortie traces the fundamental loneliness to the days of the one-room schoolhouse, when teachers worked in isolation because the other adults (and some of the children) were busy farming. These days, there are more personnel and more students associated with each classroom, but each teacher still faces a room full of pupils alone.

What do teachers do? They do what any of us would do. They make it up.

*

That day in November, Magdalene Lampert’s gamble to call on Awad—carefully calculated, in her case—paid off. Awad played exactly the role she had hoped, correcting Richard’s imprecision about 13.5 without trampling over his accomplishment in getting there.

“Ummm,” Awad had said with his typical deliberation. “I think it’s thirteen point seventy-five.” Richard kept his composure, and in the minutes that followed, Magdalene untangled a series of teaching problems. She called on Anthony, who had been waving his hand in the air, but didn’t let him go on too long and even distilled a clear, concise idea from his confusing, if enthusiastic, speech.

She then gave the floor to a girl, Ellie, balancing the gender of speakers and thereby minimizing the idea that only boys can do math, which paved the way for an astonishing performance by another girl, Yasu, who constructed a sophisticated logical proof that recalled Richard’s original insight about the relationship between doubling and halving. All this had happened in just a few minutes. But now, it was beyond time for class to end. The teacher who was to take over the room after math ended stood at the back of the classroom, giving Magdalene a look.

“You know what I think?” she said to the class, nodding at the teacher in the back. “I think that we are going to schedule a little time on remainders and division. ’Cause I think we are getting a little mix—We are mixing up a lot of ideas here and we don’t have time to go into them.”

She paused again. She wanted to give anyone who might be deeply confused one last chance to ask a question. The students sat before her, their math notebooks still open in front of them: Richard in the front, Awad in the back, Catherine to her right. All of them would be there tomorrow too, and the next day and the next and the next, until summer.

“Okay?” Magdalene asked, turning the statement into a slight question—a door just on its way to being closed. No one said anything.

Okay.

*

Both sides of the “teacher quality” debate tend to depict the challenge as a transfer problem—how to help unsuccessful, often low-income students (like the ones I cover as a reporter in New York City) to access the experiences enjoyed by their more affluent peers (like the ones I had attending public school in the manicured Washington, DC, suburb of Montgomery County, Maryland).

The accountability argument holds that suburban schools have the best teachers because, with rich coffers and newer, prettier buildings, they are able to lure top talent. To rebalance this unequal distribution, Obama has supported measures to tempt high-quality teachers back to school districts serving poorer populations. Proponents of the autonomy argument, meanwhile, contend that teachers working with the poor have paradoxically received the least freedom and the most restrictive working environments. Make their schools look more like those enjoyed by the children of the wealthy, and they will be able to prosper.

Again, neither description is wrong, but as prescriptions, both are incomplete. Teachers at affluent public schools do enjoy, on average, better working conditions and more flexibility. But they are also victims of the natural-born-teacher hypothesis. Indeed, the more I learned about successful teaching, the more I realized how rare it is, even in the schools with the most resources.

Excerpted from "Building a Better Teacher: How Teaching Works (And How to Teach It to Everyone)" by Elizabeth Green. Copyright © 2014 by Elizabeth Green. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.”

Shares