The past week saw two accusations of plagiarism leveled against celebrated works, Rick Perlstein's new book, "The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan," and the HBO series "True Detective," created by Nic Pizzolatto. The week also marked the withdrawal from an election campaign of a U.S. senator, John Walsh, D-Mont., following New York Times revelations that he had plagiarized much of his final paper in a master's degree program at the United States Army War College in 2007.

Plagiarism charges are, obviously, serious -- serious enough to scuttle a political career or get a novel yanked from the marketplace (as happened to both "How Opal Mehta Got Kissed, Got Wild, and Got a Life" by Kaavya Viswanathan in 2006 and "Assassin of Secrets" by Q.R. Markham in 2011). Making such an accusation is a dramatic, attention-grabbing move, and it often seems to fill the sails of the accusers with the hot wind of righteous indignation. Comments threads fill up with thrillingly adamant remarks like "It's wrong. Period. He should be fired immediately and his fields sown with salt" (or the professional equivalent thereof).

What none of this acknowledges is just how commonplace plagiarism charges are, how thin most of the evidence is and how poorly the average person understands the nature of the transgression. Perhaps you have to be a literary journalist or editor to realize that just beneath the surface of conventionally reported news simmers a vast sea of semi-formed resentments, grievances and paranoia about intellectual theft, each believed in wholeheartedly by a handful of crusaders (or maybe just one) yet failing to convince more objective reporters. We're a plagiarism-obsessed society, partly because we know how much damage we can do to someone's career and life by accusing them of it, but largely because so many of us don't really grasp what plagiarism is.

Sen. Walsh's case meets the simplest and most clear-cut definition of the offense. It happened in an academic context and all such institutions maintain explicit and official policies, detailing what constitutes plagiarism and what penalties will be levied against those who engage in it. Students (even students for advanced degrees) go to school to learn from people who know more than they do, to absorb and contemplate the work of those who have gone before them. For that reason, universities must take pains to draw the line between a well-informed and -sourced work and an unacceptably derivative one, and draw it as finely and as brightly as possible. Walsh copied many passages from many sources, word-for-word, without quotation marks or attribution, a clear violation of any university's academic standards.

Newspapers and other journalistic institutions, particularly high-profile operations with a great deal invested in their reputation for authoritativeness, have their own, and different, regulations regarding the use of other writers' work. When, two years ago, Fareed Zakaria, an author and pundit on politics and international affairs for Newsweek, CNN and Time, published a column on gun control in Time, he paraphrased a paragraph from a piece by New Yorker writer Jill Lepore that, in turn, summarized the work of a historian of the subject. The information in Lepore's paragraph was organized and presented in the same way, but with slightly different wording, and Lepore's article was not cited. Zakaria apologized, and was suspended by both Time and CNN. After a review of his previous commentary for them, both news organizations concluded that the incident was isolated (some outsiders have suggested that it was the work of a research assistant for the stretched-thin pundit), and reinstated him after six days.

Much greater disgrace awaited the pop-neuroscience writer Jonah Lehrer, who in 2012 was accused of the peculiar misdemeanor of plagiarizing himself. He had recycled material he had already published in a variety of newspapers as blog posts for the New Yorker, as well as in one of his books. Since Lehrer owned the work in question, this might not seem like much of a no-no -- and had the reuse occurred in, say, the Huffington Post, most likely no one would have complained. They were his words, after all.

But the New Yorker had hired Lehrer as a staff writer. The magazine is considered a platinum-standard journalistic institution that pays its writers a living wage and therefore has the right to demand complete originality. Lehrer appeared to have broken faith with his employers rather than with the reading public at large -- until, that is, Michael C. Moynihan of Tablet magazine discovered that Lehrer had also fabricated quotes, attributed to Bob Dylan, in his book "Imagine." Shortly thereafter, journalism professor Charles Seife was asked by Wired magazine to scrutinize Lehrer's work for that publication. He found 22 instances of "recycling," outright plagiarism of other writers, copying of press releases (somewhat of a gray area, since these are written in the hope that they will be regurgitated by the press) and fabrication. Lehrer's career crashed and burned.

So even in the upper echelons of journalism, where writers are often required to sign contracts promising to abide by strict ethical standards, the significance of plagiarism is a matter of context. Zakaria erred on a minor scale and had a body of solid, respected work to serve as a counterbalance, so his reputation was quickly redeemed. Lehrer, whose self-plagiarism might go unremarked in other contexts, turned out to have committed the greater journalistic sin of making stuff up and to have inserted all sorts of fishy stuff into his work from the start. His reputation toppled. Ironically, the man in whose mouth Lehrer most liked to place his invented quotes, Bob Dylan, was also found to have plagiarized many passages in his 2004 memoir, "Chronicles, Vol. 1," from sources as diverse as Time magazine and the profanity-spouting screenwriter Joe Eszterhas. But no one is going to deny the overweening originality of Bob Dylan.

Something else surely figured in the Zakaria affair, even if none of the news organizations or Zakaria himself ever mentioned it, and that is the source of the original plagiarism accusation: a conservative website called Newsbusters. Zakaria had been the target of spurious charges of "stealing" from other right-wing journalists before, such as Jeffrey Goldberg's allegation that Zakaria "lifted" a quote from Goldberg's interview with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu; in truth, Zakaria quoted Netanyahu without specifically naming Goldberg as the interviewer. Goldberg's charge was, of course, a ludicrous reach, taking a pervasive form of journalistic usage ("X said in an interview last week") and tarting it up as larceny. If Zakaria had been a political compatriot of Goldberg's it would, no doubt, have passed without notice or comment.

A similar ulterior motive lies behind the accusations of plagiarism leveled against Rick Perlstein by author and consultant Craig Shirley this week. As Salon's Dave Dayen detailed on Wednesday, Shirley claims that Perlstein infringed on the copyright of his 2005 book, “Reagan’s Revolution: the Untold Story of the Campaign That Started It All.” In letters to Perlstein's publisher, Simon & Schuster, he demanded, according to the New York Times, "$25 million in damages, a public apology, revised digital editions and the destruction of all physical copies of the book." The 19 alleged infractions in Perlstein's 880-page history include citing of historical facts and paraphrasing descriptions of events that Shirley witnessed (and Perlstein didn't) with attribution. (For a more in-depth account of Shirley's charges, see Dayen's excellent piece.)

While kibitzers like to pronounce on plagiarism cases as if they are cut-and-dried affairs, in truth, most accusations come with some sort of baggage -- even if it's usually not as glaring as Shirley's. If Perlstein were a right-wing compatriot offering a vision of Reagan as worshipful as Shirley's own, no ruckus would have been raised, no letter addressed to Simon & Schuster and certainly no $25 million demanded along with the pulping of tens of thousands of books. Granted, in this instance, Perlstein's he writes epic syntheses incorporating the work of many other writers, as well as digging up new facts from primary sources -- leaves him vulnerable to bad-faith charges when he covers material that has been covered before. But that's why Perlstein cites his sources so scrupulously -- 125 times in the case of Shirley's book -- and has published a comprehensive, hyperlinked notes section for "The Invisible Bridge" online. He can't be credibly accused of dishonesty.

The problem of plagiarism grows almost impossible murky when it comes to the arts: literary, musical, visual and performing. There are no official guidelines novelists or filmmakers are expected to abide by when they sit down to create. All literature is an immense web of influences, borrowings and allusions, from the preexisting plots Shakespeare adapted into his plays to the dozens of allusions David Lynch incorporated into "Twin Peaks." Lynch made the only witness to Laura Palmer's death a bird named Waldo whose veterinarian is named Dr. Lydecker, after Waldo Lydecker, a crucial character in the great 1944 Otto Preminger film, "Laura," about the search for a dead girl of that name.

To the best of my knowledge, Lynch has never stated his obvious debt to the Preminger film, but then he wouldn't really have to; "Laura" is a celebrated cinematic classic. The more charitable way to view the accusations against Nic Pizzolatto's "True Detective" by bloggers from the fandom of cult writer Thomas Ligotti is that they believe Ligotti's relative obscurity calls for more vocal recognition from Pizzolatto. The "True Detective" creator has been nominated for an Emmy; meanwhile, Ligotti's book-length philosophical essay, "The Conspiracy Against the Human Race," was published by the tiny Hippocampus Press and the author writes about the pointlessness and misery of existence from relative reclusion in (appropriately enough) Detroit.

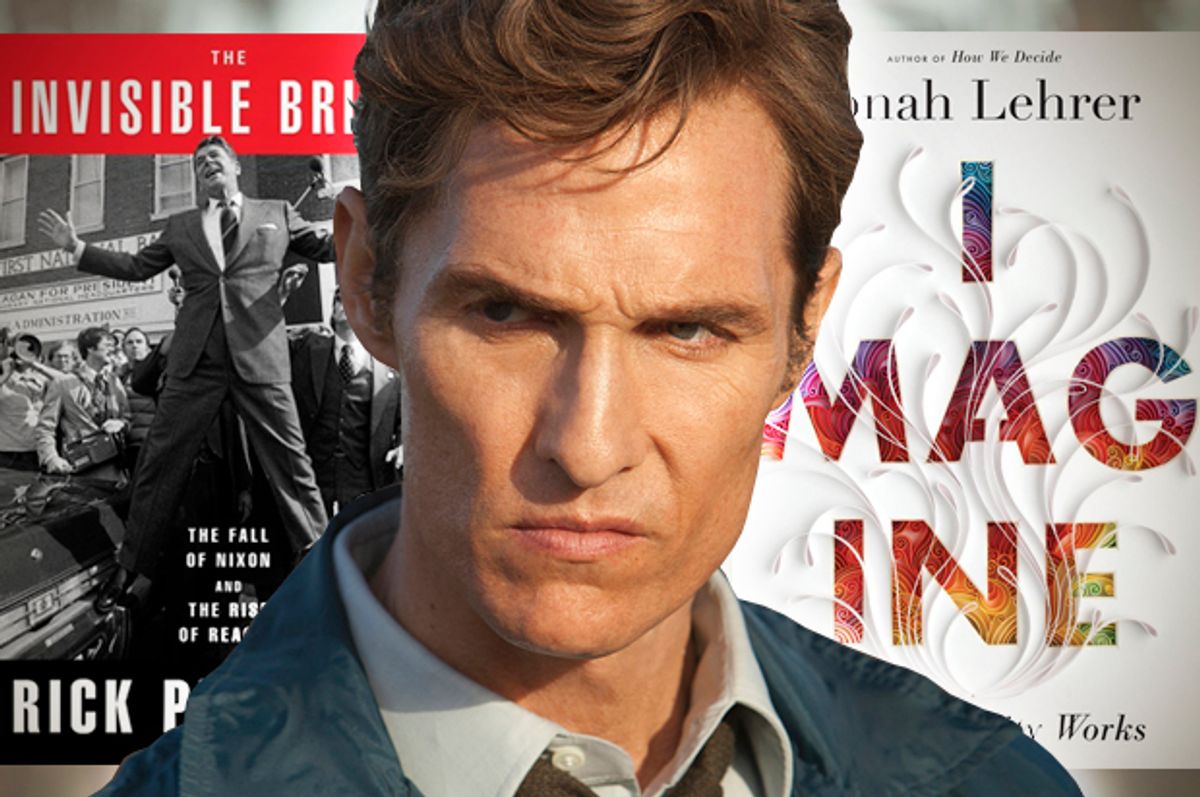

Pizzolatto's primary prosecutor is Jon Padgett, of the website Thomas Ligotti Online, although the best explication of his charges is by Mike Davis and appears on a site called the Lovecraft eZine. Padgett's case consists of lines from the dialogue of Rust Cohle -- a police detective with a pitch-black view of the human condition, played by Matthew McConaughey -- juxtaposed with passages from "The Conspiracy Against the Human Race."

At most, the similarities between the two texts consist of a word or two at a time, plus the odd clause. Most of the identical phrases ("should not exist by natural law" or "everybody is nobody") are generic enough to indicate Ligotti's influence (an influence Pizzolatto has acknowledged) without suggesting deliberate borrowing. (Only the use of the word "thresher" constitutes an even remotely striking similarity.) As evidence for plagiarism goes, this is thin gruel, and so Padgett and Davis resort to citing the University of Cambridge's ethical guidelines, which also place beyond the pale “paraphrasing another person’s work by changing some of the words, or the order of the words, without due acknowledgement of the source” and “using ideas taken from someone else without reference to the originator."

The problem is, those are guidelines for academic writing, not fictional teleplays. For "True Detective" to constitute plagiarism in any paraphrasing of Ligotti's ideas -- ideas that appeared originally in a piece of expository writing -- "True Detective" would also have to be a work primarily concerned with the presentation of original ideas. Which it patently is not. Fiction may sometimes contain ideas, but that's not what it's made of. It was no more an ethical violation for Pizzolatto to incorporate some of Ligotti's ideas into his detective series than it was for Camus to incorporate existential ideas into "The Stranger."

Davis has since posted an additional statement to the Lovecraft eZine responding to commenters who have pointed out that the Ligottian elements of "True Detective" do not even remotely rise to the legal definition of plagiarism. He does not quarrel with that judgment, but insists that even if Pizzolatto's actions don't constitute a crime, he still believes them to be "wrong."

At issue for Davis and Padgett seems to be less the use of Ligottian elements in "True Detective" than Pizzolatto's failure to pay sufficient tribute to Ligotti. The show runner only acknowledged Ligotti's influence when he was, as they put it, "cornered." He does not mention Ligotti in the DVD commentary. Where other viewers might see a winking allusion to an in-crowd of the cognoscenti, they see ... what? Do they really believe that Pizzolatto is trying to pass off Ligotti's ideas as his own? If so, he's picked an eccentric way to do so, and may be the only nihilistic philosopher to choose the writing of television detective dramas as a means of advancing his theories.

And even if that is what Pizzolatto was trying to do, I'd argue that the mad stroke of transfiguring Ligotti's dark musings -- as plummily sardonic as a Vincent Price character mainlining Schopenhauer -- into a cockeyed, Southern-fried, buddy-cop procedural is so original as to summarily absolve him of all charges of copying. This is what artists do, guys, and what they have always done. And if you don't believe me, a perusal of Jonathan Lethem's celebrated essay, "The Ecstasy of Influence," would not go amiss right about now. One taste:

Any text is woven entirely with citations, references, echoes, cultural languages, which cut across it through and through in a vast stereophony. The citations that go to make up a text are anonymous, untraceable, and yet already read; they are quotations without inverted commas. The kernel, the soul — let us go further and say the substance, the bulk, the actual and valuable material of all human utterances — is plagiarism.

Yes, actionable plagiarism does exist in fiction. The outright copying of paragraphs and pages is most decidedly wrong and has gotten many a thieving writer into hot water. But art and literature are promiscuous: They sleep around, and as a result they breed strange new and occasionally beautiful monsters that do not always bear the legitimate names of their fathers. If you find that intolerable, you're in the wrong part of town -- the university is across the road. And if, on the other hand, you were just trying to win a little more attention for your guy -- well, that was pretty clever. The paperback of "The Conspiracy Against the Human Race" is currently No. 1,076 on Amazon's bestsellers list.

Editor's note: This article has been revised since its initial publication. It originally stated that Rick Perlstein's work did not include "digging up new facts from primary sources." However, this is not the case, and changes have been made to the article to reflect as much.

Shares