Michael Brown was just a kid on his way home when he was shot and killed by police in Ferguson, Missouri. Eric Garner, a dad six times over, was breaking up a fight in his neighborhood when police in Staten Island, New York, put him in the illegal chokehold that would ultimately kill him. Marissa Alexander's infant daughter was still in the NICU when Alexander was thrown to the ground and choked by her abusive husband, leading her to fire the warning shot that Florida State Attorney Angela Corey believes should put her in prison for 60 years. The systemic racism that lets cops get away with murdering black teenagers or permits prosecutors to disregard black women's right to self-defense is blind to their statuses as sons, brothers, daughters, mothers, wives, partners. Our outrage over these injustices should be blind to these things, too -- their lives have value regardless of who knows or loves them.

But pointing out that Brown was someone's son, that Garner someone's father and Alexander someone's mother is one way to recognize that police violence and the racism of the criminal justice system are reproductive justice issues. The mainstream political discourse often fails to acknowledge this, but women of color within feminism and the reproductive justice movement have long been making these connections. Imani Gandy, senior legal analyst at RH Reality Check, noted in the wake of Brown's death, "I saw so many people on Twitter saying 'I don't want to have/raise black children in this country.' That is a reproductive justice issue."

And Hannah Giorgis wrote of the dangers and anxieties faced by black families in a piece this week for the Frisky:

I do not hear this aspect of Black parenting — this wholly rational fear that babies will be snatched from our arms and this world before their own limbs are fully grown — addressed by white advocates in gender equality and reproductive justice. Is it not an assault on Black people’s reproductive rights to brutally and systematically deny us the opportunity to raise children who will grow to adulthood, who can experience the world with childlike wonder? Is it not an assault on Black people’s reproductive rights to tell us we give birth to future criminals and not innocent children, to murder one of us every 28 hours and leave a family in mourning?

The realities faced by parents, children and families of color in the United States are so often left out of how the reproductive rights movement and mainstream media covers reproductive issues. We saw this again earlier this month when a New York Times piece on the move away from the language of "choice" failed to include the expansive, intersectional work of the reproductive justice movement, and the women of color who shaped and continue to drive it forward. When it comes to bodily autonomy and ensuring that all people can meaningfully control their own lives, pro-choice is not -- has never been -- enough.

In addition to the essential issues of access to affordable contraception and abortion care, reproductive justice is just as much about the issues of birth, parenting and family separation, among others. Raising a child, no matter who is doing it, is a lifelong endeavor. Every possible issue -- poverty, access to education, the availability of affordable healthcare, housing -- touches it, and the intersections of these issues make parenting possible or impossible. This was the impetus for the reproductive justice movement, and this is all too often what gets lost in mainstream, mostly white, discourse that centers abortion rights and contraception as the full scope of women's issues.

"It seems to me reproductive rights is really singularly focused on abortion rights and contraceptive rights," Gandy told Salon. "But those sort of rights aren't the full spectrum of concerns that women of color, particularly black women, have. Especially considering the statistic that every 28 hours a black man is gunned down by the police [or security guards and so-called vigilantes]. That means that every 28 hours a mother somewhere is losing her son.

"And as reproductive justice becomes more mainstream, the people promoting it start to erase its origins," she continued. "Reproductive justice was developed by black and Latina women, but women of color are being erased from a movement that they created."

"How do we honor how this work happens?" Giorgis asked, addressing this issue of erasure. "The ways in which I have really learned have been through the work of other women of color. Whenever I think of what I want [to see more of in the mainstream reproductive rights movement], it's honoring that existing work and how it's tied into a very long legacy," she told Salon.

In addition to the advocacy and organizing of collectives like SisterSong, national organizations like the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health and local groups like SisterReach and the Prison Birth Project, there are millions of regular people out there doing the work. The movement against the criminalization of black parents and black children, to defend the dignity and safety of young people of color, is one led by parents, families and the communities that can act as extensions of both.

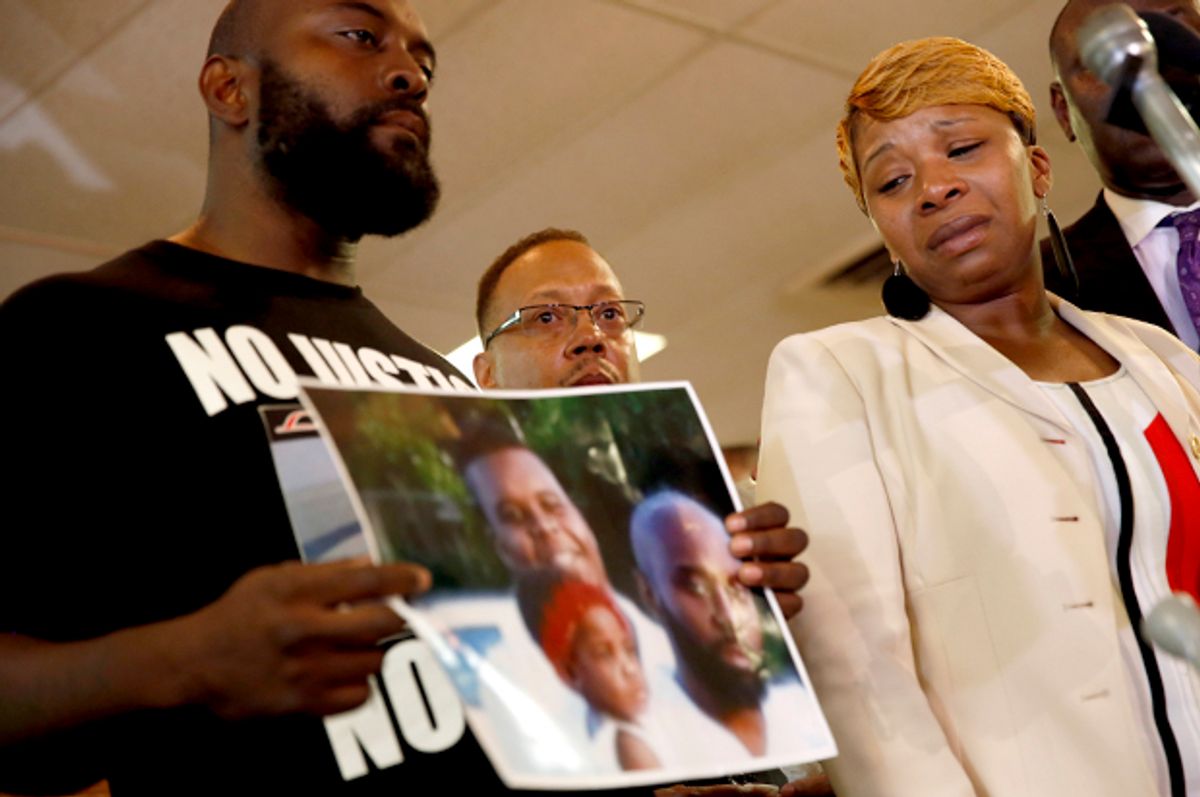

Brown's parents made these connections explicit in their demands for justice for their son. So did Sabrina Fulton, the mother of Trayvon Martin. So did Lucia McBath and Ron Davis, the parents of Jordan Davis. These parents have made it clear that the deaths of their children were not isolated incidents, but inevitabilities when police and other men with guns can act with impunity.

The realities of police violence "make it really difficult for black women to feel comfortable raising children in this environment, when any given day their kid could be gunned down in the street," Gandy said. "What you have to think about when you have a child, especially if you have a boy, you have to begin teaching them how to go about interacting with the police. And every time your child leaves the home, wondering if they are going to come back in one piece."

So when we talk about family values in the United States, the question is, "Which families have value?"

A law in Tennessee that criminalizes pregnancy outcomes will disproportionately impact low-income women and women of color whose communities are heavily policed in a way that many white neighborhoods are not. Does treating substance dependence as a criminal rather than a health issue -- in a state that has rejected the Medicaid expansion that would allow more people to access care -- value families? Does the arbitrary arrest, detention and deportation of undocumented Latina mothers in Arizona value families? Does a police force that shoots first and asks questions later value families?

As I was writing this, I saw on Twitter that the Nation's Dani McLain had also addressed these intersections and asked, "What would it take for the organizations and commentators who beat the drum for policies related to reproductive health and rights to use their platforms to advocate for black parents who lose their children to violent attacks on those young people’s lives?" A feminist movement with the stated purpose of ensuring that women and pregnant people are empowered to control their lives, reproduction and -- if and when they want them -- children and families, has to contend with these questions.

And there are always more questions to be asked. "Are children of color brought into the same life that white children live?" Giorgis remarked during our conversation. "How do we think about the climate that children are born into as part of a reproductive justice framework?"

Shares