There are two reasons why you need to watch "Mission Blue," the new documentary from directors Fisher Stevens and Robert Nixon that premiered Friday on Netflix. For one, it's a fascinating exploration of the damage we're causing in the world's oceans. And even more enticingly, it's the story of a singular, legendary woman who's made protecting the seas her life's mission.

Having begun her career in marine biology in a vastly different time -- when the oceans were still largely pristine, and when female scientists were a rarity -- Sylvia Earle has become leader in ocean research and awareness, set undersea records, raked in hundreds of awards and honors, established foundations and served as the first female chief scientist of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Nicknamed "Her Deepness," she's also been deemed a "Hero of the Planet" by Time magazine and "Living Legend" by the Library of Congress.

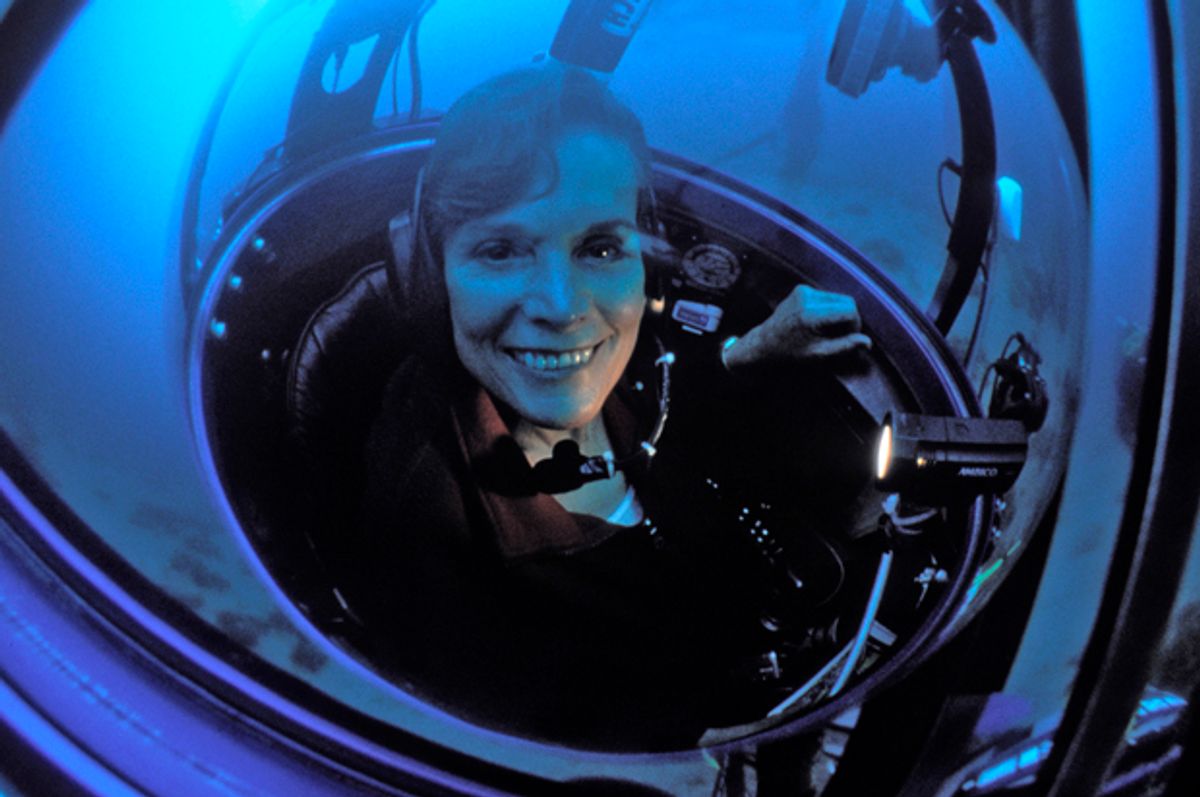

I could go on. But in seeing Earle speak, and then talking with her myself, the most fascinating thing I kept coming back to was how much she's seen. After 60 years, and having logged nearly 7,000 hours underwater, she's in a unique position to report back to those of us on land about what we're missing. "Why am I driven?" she asks. "Because I can’t put aside the things that I’ve witnessed."

Soft-spoken but forceful in her convictions, Earle had a lot to say about the good -- and the very, very bad -- of the current state of our oceans. Check out the trailer for the documentary below, then read on for our conversation, which has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

It was incredible to see the way your career kind of follows this growing understanding of what’s happening to the oceans. Near the beginning of the film, you say: "Sixty years ago, when I began exploring the ocean, no one imagined that we could do anything to harm it." Do you find that attitude has changed significantly now?

Yes, it has, but there are still many that hold to that concept that not just the ocean, but Earth itself is too big to fail. The thought is that people cannot do what so obviously we are doing -- that is, changing the nature of nature.

What are some of the biggest things you’ve seen that maybe people who don’t understand this are missing?

I think it’s amazing that we can go to a supermarket or a restaurant and see many forms of wildlife offered to us. We don’t find songbirds or eagles or owls or lions or tigers, but their equivalents from the ocean are certainly there. I think the awareness is beginning to grow that taking things from the sea isn’t harvesting -- it’s hunting.

It wasn’t that long ago, in terms of the human experience, that a large portion of what powered our civilization came from consuming wild creatures. And birds and mammals were very much a part of that. The same animals that today, by and large, are treasured and protected, in the time of Lewis and Clark were simply regarded as commodities. Well, we’re looking at the ocean now. And at the fish and the other creatures -- lobsters, clams, shrimp, oysters -- that are there, and their value as living creatures and as a part of the ecosystem that maintains a planet that works in our favor. We have taken all preceding human history to get to the point where we respect terrestrial wildlife, and we’re beginning to understand that is true with the ocean as well. I have seen that shift personally: As a kid in New Jersey, we ate locally caught ocean fish. We went out ourselves and looked for crabs and clams and things. Part of it is because we’re so depleting ocean wildlife that either we’ll stop or cut way back on what we are taking. We’ll do it consciously or they will simply disappear, as has happened with many creatures on the land. When you take too much, they simply go away. It’s not a choice anymore.

Do you think that shift will happen quickly enough for us to avoid that worst-case scenario?

We have a chance right now, but whether we exercise that knowledge or not, I guess you’ll have to wait 10 or 50 years and see. Some things may continue and be more resilient than others. Among the changes, that’s one: We’ve seen a loss of ocean life, like 90 percent of many of the big fish, the large sharks, the tunas, swordfish, halibut, cod, even the small creatures like the herring and the squid are significantly depleted from the levels they enjoyed when I was a child. We’re emptying the oceans. We have a capacity to extract on a scale that is far more effective than those systems can replenish. We talk about sustainability but we aren’t actually practicing sustainability at all.

Large-scale extraction of wildlife simply hasn’t proven to be sustainable whether on the land or in the sea. And I’m talking large scale. If you think about communities and families working within the natural systems, when you know that your day-to-day survival depends on the wildlife that surrounds you in the area that you can reach, you’re careful not to take them all. But in the ocean, most of what is taken today is taken on a large, industrial scale, and the connection between the people who consume what is taken and those who are actually doing the extraction -- there’s a very big gap. People don’t know what an orange roughy looks like, where it lives, how old it is, what it eats, what its life is like 2,000 feet beneath the ocean. All they know is that it’s being marketed and they can have a piece of fish meat. People eat lobsters so casually, not appreciating that every lobster in a way is a miracle. It starts out as an egg and goes through these amazing shifts in the plankton with mouths that are ready to gobble them up at stages all along the way until they get big enough to be able to avoid most of the "eat and be eaten" life that takes place in the plankton when they’re very small. It takes about five years to get a pound-size lobster. It takes a little longer to get a two-pounder, and lobsters can live to be as old as humans. Occasionally you’ll hear, “Oh we got a 20-pound lobster and it’s probably 50 years old.” That’s not a sustainable choice for something to eat. These big old fish and big old crustaceans or anything that takes so long to grow.

So, the changes in what we're taking out of the ocean? We've scaled up since 20th century, using weapons and technologies designed for wartime use and applying them to extract life from the ocean. Finding and returning to the same place repeatedly, traveling over long distances, navigation: All those things that have really been tremendous breakthroughs in the latter part of the 20th century and into the present time -- even weather forecasts enabling fishermen to go much further than they might have. We're also putting noise into the ocean. When I think about what the ocean had to be like in the days of sailing vessels versus today’s fossil fuel-powered large-scale and numerous ships that sail the ocean, serving markets all over the world ... So much of what holds our societies together internationally, globally, is the transport of goods by sea. And two of the biggest and most worrisome factors are the warming trend that has really been most noticeable in the last 30 years: That’s reflecting changes in the ocean by putting pressure on coral reefs.

Ocean acidification is one of those effects of climate change we hear less about, because unlike you, most people haven’t been there and seen it firsthand. It was very striking in the movie when you go to the Great Barrier Reef and see how it's changed.

And it's disrupting the chemistry of the planet as a whole. Part of that is driven by breaking the food chains in the ocean. Every time that a fish or a whale or even a shrimp eats, it also puts nutrients back into the system. There’s no waste in a natural system. In fact, having whales and dolphins and turtles and sharks travel over long distances is one of the ways that there are corridors for nitrates and phosphates and other elements that are vital to the phytoplankton that generate oxygen and take up carbon, drive the carbon cycle, drive the oxygen cycle, drive the water cycle, maintain a planet that works in our favor. By breaking those nutrient links with large-scale extraction of krill, of squid, we are disrupting these nutrient channels in the ocean. We’re changing the nature of nature. It’s just a fact. Mostly since the middle of the 20th century and at a pace that is picking up. Think of the changes.

All that seems like a load of bad news -- and it is -- but it’s paralleled with the good news of the rate of knowledge that we’re gaining, also using some of the technologies developed for wartime use. We’re applying them to understand how the planet works, who lives where. Sonar can be used to find and kill fish, but it can also be used to find and map the ocean floor to know where deep populations of fish live. It can be used to protect them as well as to destroy them. So it’s what we do with the technology. It’s not the technology that’s harmful. Like plastics, it’s not the plastics that are harmful, it’s what we do with them -- especially the single-use plastics. That’s another revolution that I’ve witnessed. I come from a time -- call it the pre-plasticzoic or whatever -- before there were plastic cups and spoons and forks and plates and the many things we used.

Some of the studies coming out now about just how much plastic is in the oceans -- it’s hard to believe.

It is, but that too is derived largely from fossil fuels, as we have begun to extract oil, gas and coal on the scale that has characterized the latter part of the 20th century and now the 21st. These products have developed that we weren't able to make before. Now we’re also able to see the downside, to recognize the enormous benefits that fossil fuels have delivered to humankind. I think it’s safe to say our prosperity would not be here, we wouldn’t have this level of health or wealth or just sheer numbers had we not tapped into this amazing source of power, of energy. But the most important thing that has given us is the communication systems, satellites up in the sky, the ability to measure the loss of polar ice. The ability to know the world in powerful new ways and to see the damage that we’re doing and to pull back from the edge, perhaps just in time. Maybe we won’t, but we have the power to choose. We can turn things in a different direction.

About half of the coral reefs are either gone or in a state of sharp decline. Fish of many kinds are, from where they were from when I was a kid, we have maybe 10 percent. In some cases maybe 20 percent. In other cases maybe 2 percent remain. But if we just take those graphs, those lines, that knowledge, that evidence and extrapolate out another 10, 20, 50 or 100 years, our prospects for a prosperous future look very dim. But we have the capacity to not only alter nature in a negative way -- we can work with nature in a positive way and turn things around. We see it in places, in the ocean where fish are given safe havens, where you just don’t kill them. True protected areas. They don’t always come back -- not all species can come back because their numbers are just too depressed. But you certainly see recovery. You see greater abundance, greater diversity and more overall mass. Biomass increases in just a couple of years, and the longer you maintain that protection, the greater the benefits -- they just keep coming as the systems get more and more stable and resilient.

Maybe one of the best defenses against ocean acidification is to have protected areas that have resilience, that have members of the coral community that can tolerate an increased acidity. If you have a system that’s damaged, that’s not healthy, it’s less able to cope with the stresses that are imposed. And fish are very much a part of that, like birds are to the land: they’re important to a healthy forest or other system. When you take fish away from a coral reef, it damages the coral, the corals die. If you take the corals away, of course, the fish die. If you rip pieces out, you’re going to have consequences and that’s what we’re seeing. Some have a magnified importance: They’re called keystone species. When they’re depleted or removed, it really has a magnified effect on the system as a whole. It’s perverse that we seem to have a knack for choosing keystone creatures, like krill in Antarctica. What ever provoked us to start traveling thousands of miles to an area where no humans have ever lived to capture the small shrimp upon which the entire ecosystem rests? You can go to almost any market or drugstore today and get krill oil -- which may have some beneficial effects to use, but we can get equivalent oil that is every bit as good for us as what they squeeze out of the little krill; we can actually grow the kinds of plants that those krill consume. Some companies are doing just that. But knowing that there are choices, that’s part of the good news. People know the harm that comes from being a market for creatures that are vital to the integrity of polar systems. They might choose not to take krill oil. They might choose to look for the plant-based sources.

Quite a few years ago you decided to leave NOAA, and in the documentary it’s portrayed as your pushing back on an establishment that wouldn’t recognize the full extent of distress and do what needs to be done to preserve and save these systems. Can you describe what the climate of the Bush administration was like then, and do you think there's been improvement from the higher-ups?

Well, my decision to return to private life was motivated by a number of things, but certainly a key factor was that, although they ask you to come because of your expertise, they require you to take the administration’s perspective. As a scientist, I have to say what I believe to be true, whether it’s the administration’s perspective or not. I’m not saying the top echelon of the government at the time I was chief scientist gave any consideration at all to the decisions of the sort that I was faced with, I mean, I don’t think they cared much.

But within NOAA there are policies, and there still are, that are greatly influenced by the commercial fishing industry. In fact, the National Marine Fishery Service does a lot of good things, but its primary purpose is to serve the interest of commercial fishing. NOAA is, after all, in the Department of Commerce. And it has almost a billion-dollar budget for serving the interests of the commercial fishing industry. The National Marine Sanctuary budget is $50 million, so there’s a disparity there: a relatively small concession to protecting the ocean and a relatively large investment going back to the 1950s and '60s and '70s, when many of the policies were made, on the basis of thinking the ocean was too big to fail, that our job was to take, that the ocean was a constantly renewable source of fish and other ocean wildlife. We’ve learned otherwise, but that notion still dominates the thinking: that we need to extract, that there’s almost an obligation to take from the ocean. There’s a goal of taking it on a “sustainable” basis but there is plenty of evidence accumulated over the past 50 years that whatever it is we’re doing isn’t working.

The U.S. policies are really better than most other nations that have fishing policies. We have the Magnuson-Stevens Act, we have been trying to get it right, to look at populations and to work with a system, have areas of closure. But in the end, when you put it all together, you say, what’s the reason we have this agency? Our goal is to facilitate the extraction of ocean wildlife for market purposes. The reason they started calling me the "sturgeon general" at NOAA was because I kept making comments about taking care of the fish, speaking for the fish. We have this idea that our job is to go capture them and the cost is accounted for in the cost of the ships, the cost of fuel, the wages for the fishermen, the gear. We don’t put a cost or a value on the fish. They’re just there to be taken. They’re taken from everybody if they belong to anyone, and I’d like mine alive, thank you.

I wasn’t allowed to go to some of the important meetings. They knew what I’d say. They didn’t want to have it said. When I learned that 90 percent of the Bluefin tuna from the North Atlantic were gone, that was the one meeting I did go to. I just blurted out, “Are we trying to exterminate them? Because if so, we’re doing a great job. We only have 10 percent left to go. Woo hoo!” But the odd thing is, even though the evidence was there from the fisherman’s own records that we had taken, in a little more than 20 years, 90 percent of that species out of the system, we were still taking them and looking for ways we could continue killing them. And we’re still killing them. And in the South Pacific, the latest figures are 4 percent of the Bluefin tuna, and yet they’re still being killed because, as the quantity goes down, the price goes up, because there’s been a great marketing ploy around the world to favor the consumption of Bluefin tuna. It’ll be a short-lived phenomenon because if we continue doing what we’re doing at the rate we’re doing it, there won’t be Bluefin tuna. There can’t be. All you have to do is look at the trend. Here they were, here’s where they are, keep doing what we’re doing, look at where they’ll be. It’s not rocket science, as they say. You don’t need to be a math genius, like duh.

Do we have the ability to restore or fix some of the places in the ocean that have already come close to being destroyed, or should the focus now just be on saving the rest and preventing further harm?

I think a priority should be to protect those areas that are still in pretty good shape, on both land and sea. You identify areas that are really important, whether they’re breeding areas or feeding areas or intact forests or marshes or whatever they are. Do what you can to save them while they’re still in good shape. But coupled with that, restoration is a critical part of the plan for getting a planet back on an even keel.

The film shows Cabo Pulmo, in Mexico, where for 15 years the whole area has been off limits to taking. People go there -- the local people are deriving livelihoods from a living system where people go to visit, to dive, to enjoy the beautiful landscape and seascape. And the fish have significantly recovered. You actually see big grouper, scenes in the film of this tornado of jacks that represent part of the return of prosperity for that relatively small area in the ocean. It’s 27 square miles, a little patch of blue where even the fish are safe.

And the president of Palau, at Secretary Kerry’s ocean conference in Washington in June, turned heads when he made the announcement of his country’s intent to protect their entire exclusive economic zone: All of the area of the shore out to 200 miles, an area the size of France, where they’re going to exclude commercial fishing. They see the greater value of an intact system versus one that is being exploited. More than 80 percent of the people who go to Palau go there for swimming or snorkeling and diving. The ocean is their revenue source. They grow food, of course, and they rely on the sea for some of their vital food sources. But they’re saying, “We’re going to keep out the large scale fishing because it’s damaging the systems we actually value intact more than selling off pieces for short term gain.”

But communication is a key. If you put your life, your world, your existence in the context of the world as a whole and how things work, you can be a lot smarter, even wise, about how you plan a future for your country, your community, for your family, or even for just you. And there are various numbers out there. Some have said, “Well, we need to get 10 percent of the ocean protected by 2020.” Others say -- and I sort of go along with this -- that it has to be at least 20 percent. Some say you need half the ocean fully protected if we are to have a planet that works in our favor.

Ocean acidification ought to be a high priority because that’s highly disruptive to the basic functioning of the processes we need to hold the plane steady, to be resilient against climate change, climate disruption, global warming. A healthy system is more likely able to resist or recover or withstand acidification. A damaged system, one that’s already suffering, is less likely to be able to withstand the impact of acidification. And so it’s like a race, as we learn the importance and the value of the living ocean. The intact ocean. We are, at the same time, increasing the pressures of the ocean from many sources. So can we get people tuned in to be aware of the consequences of the choices they make? When they choose to eat tuna, they’re part of the problem. When they choose to eat squid, that’s part of the problem too. Those squid are needed in the ocean as a part of the healthy systems that keep us alive. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it. Why am I driven? Because I can’t put aside the things that I’ve witnessed. I can’t just not want to share the view with as many people as possible so that they can make better choices themselves.

Shares