“We are our own worst enemy,” one acerbic Danish scientist observes from the deck of a three-masted schooner as it sails through the northeastern fjords of Greenland, quite likely the most remote part of the world. (I think he says it in English, but the collection of oddball characters on this voyage constantly switch languages.) He doesn’t even mean this in the philosophical or global-historical sense, although there’s plenty of that kind of talk in Daniel Dencik’s mesmerizing and spectacular wilderness documentary “Expedition to the End of the World.” (I’m well aware that the most popular venue for independent cinema is now the living room, but this is one to see on a big screen if you possibly can.) He means that the human beings aboard the old ship are so far from human civilization, and the stark landscape around them seems so devoid of life, that they are literally the most dangerous predators to be found.

Later in the film the explorers actually discover that isn’t quite true. After finding polar bear prints and scat they finally encounter one actual bear, an animal who appears half-starved and confused by the Greenlandic summer, which has rendered the fjords ice-free for a few weeks each year, for the first time in human memory. He has ransacked a remote cabin left behind by other explorers or scientists – the only human structure we see in this entire film – eaten the entire cache of canned foods and chocolate bars, and left behind a potent stench of polar-bear urine and excrement. If it’s possible to read the moods of a wild animal, this one seems both bewildered and enraged; it’s almost as if he understands on some instinctive level that the creatures who left this building and its peculiar treats behind are also responsible for his predicament.

That’s way too much anthropomorphic projection, no doubt, but “Expedition to the End of the World” is an experience that wrenches you free of the everyday world and urges you to contemplate all sorts of big-picture questions. Although it resembles familiar kinds of documentaries in obvious formal terms, Dencik’s film is profoundly ambitious and unorthodox, and offers yet more evidence of the quiet cinema and TV renaissance in the land of Kierkegaard and Lars von Trier over the last few years. (See, for instance, the political series “Borgen,” Tobias Lindholm’s Somali-piracy drama “A Hijacking” – which was far superior to “Captain Phillips” -- and the outstanding Iraq-war documentary “Armadillo” by Janus Metz, who helped conceive and produce this film.)

Set alternately to Mozart’s “Requiem” and blasts of Metallica, “Expedition” is like a stoned camping trip to an unimaginably distant location, where your companions are a group of brilliant intellectuals, artists and scientists. No underlying premise for the mission is ever spelled out, nor is the provenance of the antique vessel ever discussed. As for the mind-altering substance on this voyage, it’s not weed or LSD – although the movie does not show us everything that happens on shipboard at night – but the extraordinary setting, a pristine Arctic landscape of sea, land, ice and sky so isolated that it has never been mapped or explored. Climate change has opened the fjords of Greenland’s northeastern coast to marine traffic for the first time in recorded history, and the members of the Danish expedition were among the first human beings to enter them in thousands of years.

There is no evidence that the native people of Greenland have lived in or even visited this area in recent historical times – it’s remote and barren, and the hunting is sparse – and the only evidence of human habitation that archaeologist Jens Fog Jensen can find appears to date to the Stone Age. But a group of “petty bourgeois anarchists” from Copenhagen (to quote German artist Daniel Richter, who plays the role of class clown on the expedition) are not the only outsiders interested in the dramatic effects wrought by a warming climate on this previously inaccessible coastline. In one fjord, the Danes encounter another expedition, apparently a group of oil-company geologists and prospectors in search of the enormous petroleum reserves that are believed to lie beneath that deep, cold ocean. If Greenland’s gold rush has not quite begun, it’s coming soon.

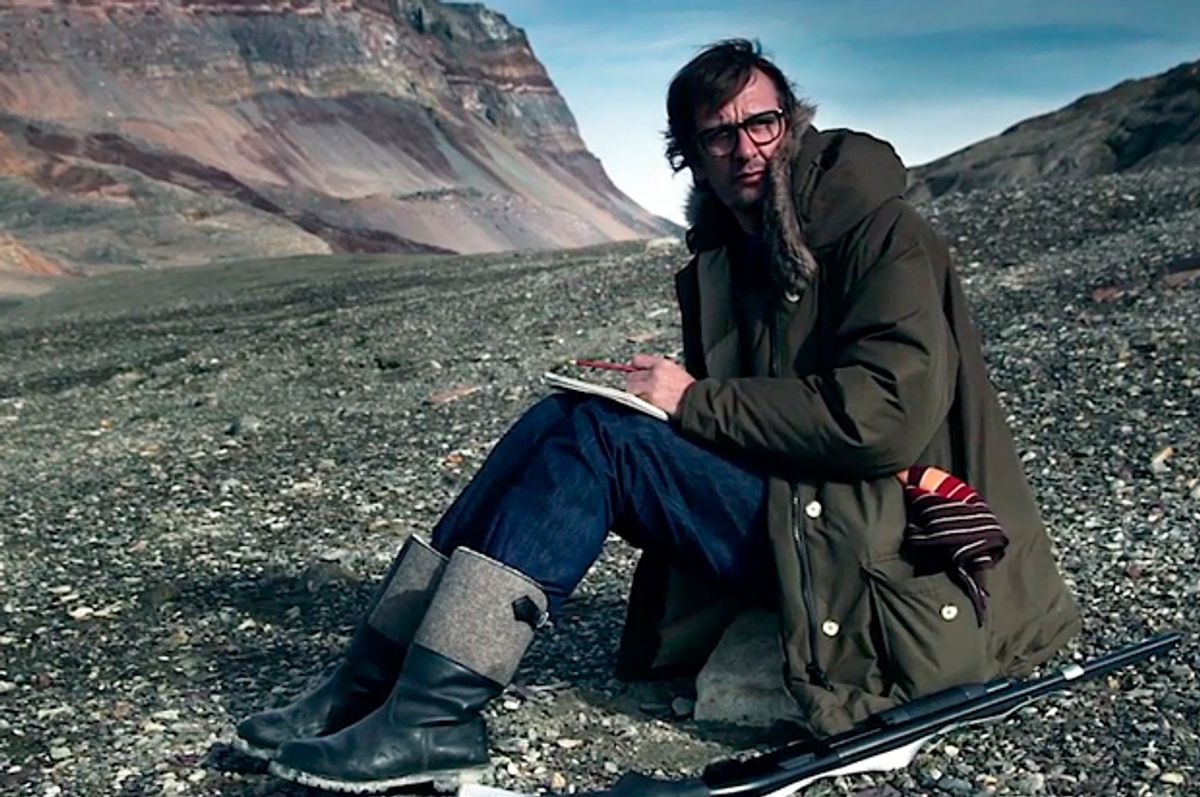

There are images in “Expedition to the End of the World” – which was shot on digital video by cinematographer Martin Munch and his team – where you feel so disoriented that you can’t tell whether you’re looking at sea or land, ice or water, fog or sky. One of the crew members, photographer Per Bak Jensen, discusses the disorder known as Stendhal syndrome, in which an experience of great personal significance, especially the viewing of artistic or natural beauty, can cause disorientation and dizziness. (The French novelist Stendhal supposedly had such an experience while visiting the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence.) This film could be understood as an attempt to induce Stendhal syndrome, and also to document it. But the goal is not purely or primarily aesthetic, as powerful as that effect is. Jensen’s own manifestation of the syndrome is to scrawl a triangle-shaped diagram in his notebook that explains “the meaning of life,” and as ridiculous as that idea is, I was almost convinced.

For one thing, this is a highly paradoxical and philosophical nature film, which shows us a pristine and remote landscape even as it is being transformed into a commodity. The Greenlandic fjords will never again be as unspoiled as we see them here; oil derricks, eco-tourists and National Geographic photographers are on their way. Yet even as Dencik reminds us of the intense fragility of the natural world, and our outsize impact upon it, his larger point may be that we are not anywhere near as powerful as we think. As Greenlandic geologist Minik Rosing observes in the film, we are the first species capable of affecting our environment so rapidly that we cannot adapt to the change, and in the long run we will pay the price for that.

It took me a while to grasp the obvious fact that the phrase “the end of the world” in Dencik’s title has multiple layers of meaning. Our activities over the past 200 years have led to a climate crisis and a mass extinction event, but against the vast, empty and inhuman landscape of Greenland, the expedition members view this questions from a dispassionate distance. Geographer Morten Rasch (who rejects Per Bak Jensen’s “meaning of life” diagram) says he is always perplexed when people ask him how he feels about climate change. He is obsessed with understanding the processes at work, and the grand, general question of whether they are good or bad strikes him as irrelevant and uninteresting.

Yes, as zoologist Jeppe Møhl tells us, that bewildered polar bear and his entire species are unlikely to survive on this rapidly transforming planet. But it is the height of human arrogance to believe that we can avoid his fate indefinitely. We use pat phrases like “the fate of the planet” when what we are really concerned about, understandably enough, is the future of our own civilization. The planet will be OK. Life on earth is a robust phenomenon that has survived worse catastrophes than anything we can inflict. All our nuclear weapons and toxic sludge and carbon emissions add up to a tiny poisonous hiccup within what Rosing calls the “very short parenthesis” that is human life on planet Earth. Dinosaurs were the dominant form of life for 100 million years or so, and at this point we look unlikely to last even 1 percent as long in that role. Greenland will still be there when we’re gone, and sooner or later the ice will be back. If we take the polar bears and Arctic foxes and musk oxen with us when we go, other creatures will evolve to take their places, and ours.

“Expedition to the End of the World” is now playing at Film Forum in New York. It opens Sept. 5 in Los Angeles, Portland, Ore., Santa Fe, N.M., and Seattle; Sept. 10 in Boston; and Sept. 12 in Missoula, Mont., with more cities and home video to follow.

Shares