Since 1948, Highlights for Children ("Fun With a Purpose") -- a magazine most of us have only ever encountered in pediatricians' waiting rooms -- has featured a cartoon called "Goofus and Gallant." Intended to teach kids the basics of courteous behavior, it stars two boys who illustrate the right and wrong way to behave in various situations. "Goofus and Gallant" has gone on to inspire some dark adult imaginings, but never before has it seemed so perfectly applicable to the book business.

That's because lately Amazon has become the Goofus of publishing news, the surly, inconsiderate and gauche kid who never seems to get anything right. This is not to say that Amazon is any less powerful in the marketplace or less likely to triumph in its ongoing war against book publishers. But on the P.R. front, in its most recent battle against the Hachette Book Group, the online retailer has stumbled again and again. (Full disclosure: My 2008 book, "The Magician's Book," was published by Little, Brown, a Hachette company.)

According to a recent profile in the British newspaper the Guardian, the mastermind behind Amazon's dubious public relations binge is Russell Grandinetti, a senior vice president at Amazon. He's characterized by the paper as in charge of "digital books strategy, the highest-profile role within the company" and as having "a good claim to be the most influential person in publishing." The paper also states that publishers view him as "some sort of evil genius." Now, as anyone obliged to report on the industry can attest, book publishers tend to be easily spooked sorts who perceive themselves as moving through a dangerous environment stalked by large predators. "Evil" is surely pushing it. By the same measure, although Grandinetti is widely regarded in the book industry as a very smart guy, Amazon's recent fiascoes in the image department suggests that the "genius" part might be pushing it as well.

Amazon's troubles began in early May, when David Streitfeld of the New York Times first reported that the retailer was hampering its customers' access to Hachette titles, as well as trying to deflect them to other books, all as a means of forcing the publisher to agree to new wholesale terms. (Although neither party is supposed to discuss the details of the negotiations publicly, it's quite clear by now that they involve the price of e-books.) Amazon had applied similar strong-arm tactics in negotiations with publishers before, such as pulling buy buttons from all Macmillan titles during a dispute over e-book prices in 2010, but those actions were short-lived. As the standoff with Hachette dragged on, the Times published story after story, recounting how Amazon's punishment of Hachette was hurting authors and inconveniencing its customers by making them wait as long as three weeks to receive the Hachette titles they ordered.

One of those authors, TV personality Stephen Colbert, made the sins of Amazon against authors a running theme on his popular late-night comedy series. "Watch out, Bezos, because this means war," he announced. And it was. Colbert took the impasse as an opportunity to promote lesser-known Hachette writers like Sherman Alexie, who came on the show to accuse Amazon of trying to amass a "monopoly," and he directed would-be book buyers to the Portland, Oregon, independent bookseller Powells.com. Like Streitfeld, Colbert devoted multiple stories to the issue, all with Amazon cast as the baddie.

Amazon has long been a tight-lipped operation, refusing to release hard information to the press (which to this day has never received figures on just how many Kindle e-readers the company has sold) and communicating through the rather arcane medium of the forums on its own site. This strategy, however, was patently inadequate to the sudden onslaught of high-profile bad press. It kept coming, too, zeroing in not just on the company's dealings with book publishers, but also on its impact on the economy and its own workforce. In July, British children's book author Allan Ahlberg turned down a prestigious prize funded by Amazon to protest the company's "tax avoidance" in his country. "For my part, the idea that my ‘lifetime achievement’ ... should have the Amazon tag attached to it is unacceptable," Ahlberg told the Bookseller magazine.

In early July, Amazon attempted to detach Hachette's authors from their publisher's side by offering to restore their books to full availability on the site and to temporarily funnel all of their own revenue from Hachette's books to the authors, provided Hachette would do the same. No one bought it. "This seems like a short-term solution that encourages authors to take sides against their publishers," observed Roxanna Robinson, president of the Authors Guild, to the New York Times. "It doesn’t get authors out of the middle of this — we’re still in the middle."

Then, late last month, the bestselling novelist Douglas Preston began to collect signatures on an open letter addressed to the retailer, demanding that it cease treating authors as "cannon fodder" in its negotiations with publishers. Authors famous and obscure, published by Hachette and not, signed it -- 900 of them, under the rubric Authors United. That letter was published as a full-page advertisement in the New York Times last week.

All of these criticisms forced Amazon to respond in a fashion to which it was not accustomed: via public statements issued to the press and direct communication (i.e., email) to customers. Its lack of experience in such communications showed. When Publishers Weekly approached the retailer for comment on a conversation between Grandinetti and Preston in which Grandinetti reportedly asked Preston to quiet his protest, an Amazon spokesperson accused Hachette of using its authors as "human shields," a highly untimely bit of hyperbole. Another spokesperson told the Guardian that Preston was "entitled" and an "opportunist." Of course, Preston had himself described Amazon's behavior as "thuggish," but public relations is not a rational art; insults that sound merely intemperate from the mouth of a novelist in a shed (a New York Times article on the petition came with a photo of Preston standing in his "writing shack") register as ominous and bullying as part of the official response of a gigantic corporation.

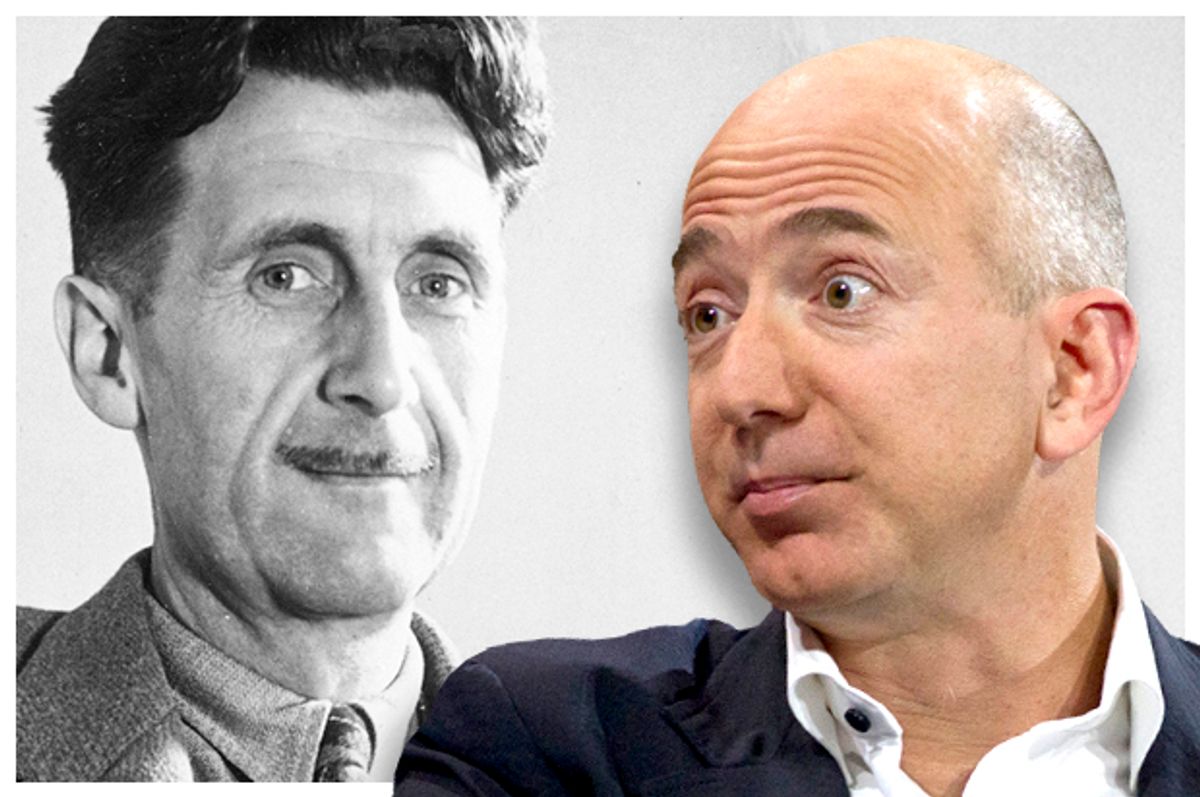

To top it all off this month, the retailer posted an open letter at the url for something called Readers United. Bitingly sarcastic, the letter indicted the "literary establishment" for resisting Amazon's efforts to set e-book prices at $9.99, invoking George Orwell as one such defender of the establishment, noting that in a 1936 article Orwell called on publishers to "suppress paperback books." Oh, Goofus! The Orwell quote Amazon used was promptly revealed to have been taken out of context, and on top of that reminded many observers of an earlier scandal in which Kindle owners who'd bought Orwell's "1984" had their copies erased from their devices. Contrary to Amazon's assertion, Orwell was in fact endorsing paperbacks. His literary executor sent a letter to the New York Times likening Amazon's letter to the "doublespeak" employed by the totalitarian Ministry of Truth in "1984."

Significantly, Amazon emailed the same letter to an unknown (but presumably large) number of self-published writers who use its Kindle Direct Program. Why such authors should care about the pricing of traditionally published books was not explained. (Furthermore, as I've argued in the past, self-published writers obtain a crucial economic advantage when traditionally published books are priced higher than their own.) A blogger named Eldritch on Io9's Observation Deck memorably described the missive as "rambling" and "very bizarre," "like a screed from a sincere (and sincerely crazy) ex-boyfriend posting on some weird listserv." Meanwhile, the Guardian's admiring portrait of Grandinetti was promptly followed by the news that over a thousand German-speaking authors have published an open letter to Amazon protesting that it "manipulates recommendation lists" and "uses authors and their books as a bargaining chip to exact deeper discounts" from European publishers.

Yet Amazon does have its partisans -- specifically, the authors who use its self-publishing programs and whose books are published by its imprints. Nearly 8,000 of these signed a verbose petition at Change.org calling for Hachette to capitulate. (If there were ever a document to suggest that self-published writers are insufficiently edited, it's this one, even though it begins with a promise to be concise.)

This is Amazon's core constituency, one whose loyalty is fueled by gratitude for the technological innovation that has permitted them to publish their e-books and also by loathing for the publishing "oligopoly" that has denied them publication the old-fashioned way. The Readers United letter, with its misquoted Orwell, its bitter asides ("Well … history doesn't repeat itself, but it does rhyme") and its vaguely conspiratorial/messianic tone ("the powerful interests of the status quo are hard to move") may sound like "full-out crazy town" to Eldritch, but it is the native tongue of the indie author community.

Amazon much resembles a political party that hasn't figured out how to recalibrate its rhetoric to appeal to voters outside its base. Its pronouncements come in Amazonspeak, a language bred in a corporate echo chamber and the cheerleading threads of its self-publisher forums. Hence, its incessant harping on the fact that Hachette is owned by the "$10 billion global conglomerate" the Lagardère Group -- itself dwarfed by Amazon's own $90-billion valuation. (As Preston pointed out in the Times, conglomerates jettison or downsize insufficiently profitable divisions all the time, so to pretend that Lagardère will blithely absorb Hachette's losses is absurd.)

These and other attempts to cast the mega-retailer as a nimble, innovative yet embattled outsider allied to "the little guy" -- gestures that strike most observers as ludicrous -- nevertheless ring true to self-publishers, who have been known to describe the five largest traditional book publishers as a "cartel." Amazon, in their view, has rescued them from the obscurity to which they'd been abandoned by big-time "legacy" publishing. The retailer certainly has other fans, busy consumers who love being able to order batteries, shampoo or water filters from their laptops and get free second-day air shipping. But people who prize you primarily for not taking up too much of their time and energy are not the stuff that communities are made of.

Hachette itself barely exists in the public's mind, but authors are the only face of the book business visible to the average reader, and they have made their position clear. The signatories of Preston's petition include such household names as James Patterson and Nora Roberts and such literary darlings as Junot Diaz and Mary Gaitskill, as well as YA titans like Suzanne Collins and Lemony Snicket. Amazon loyalists have taken to calling these writers "one-percenters," but that epithet belies a crucial fact: The influence and income of any successful author derives from the simple fact that lots and lots of readers like his or her books and often, by extension, the author as well. Amazon may be the BFF of the self-published author but the average reader is still more likely to listen to Stephen King.

It's almost enough to make you feel sorry for Amazon, which for all its wealth and power has never bothered to develop the skills to participate in a wider public conversation about its role. The retailer is now up against a whole lot of people whose expertise is exactly that: communicating with the world. The real war between Amazon and Hachette, the economic one, remains up in the air, but the war of words is all over but the shouting.

Further reading

Profile of Russell Grandinetti of Amazon by Edward Helmore for the Guardian

David Streitfeld's original report on the Hachette-Amazon standoff for the New York Times

"Writers Feel an Amazon Hachette Spat" by David Streitfeld for the New York Times

Stephen Colbert declares war on Amazon

Children's book author Allan Ahlberg declines Amazon-funded lifetime achievement award

Amazon's offer to Hachette authors, with response from Roxana Robinson of the Author's Guild, in the New York Times

Open letter from Authors United to readers regarding the Amazon-Hachette dispute

Douglas Preston describes Amazon's requests that he "quiet down" in Publishers Weekly

Amazon spokeswoman describes Douglas Preston as "entitled" and "opportunist" in the Guardian

Amazon's "Readers United" letter, misquoting George Orwell

Eldritch of Io9's Observation Deck on the Readers United letter

"Stop fighting low prices and fair wages," a petition at Change.org in defense of Amazon

Correction: An early version of this article failed to disclose that Laura Miller's 2008 book, "The Magician's Book," was published by Little, Brown, a Hachette company. This omission has been corrected.

Shares