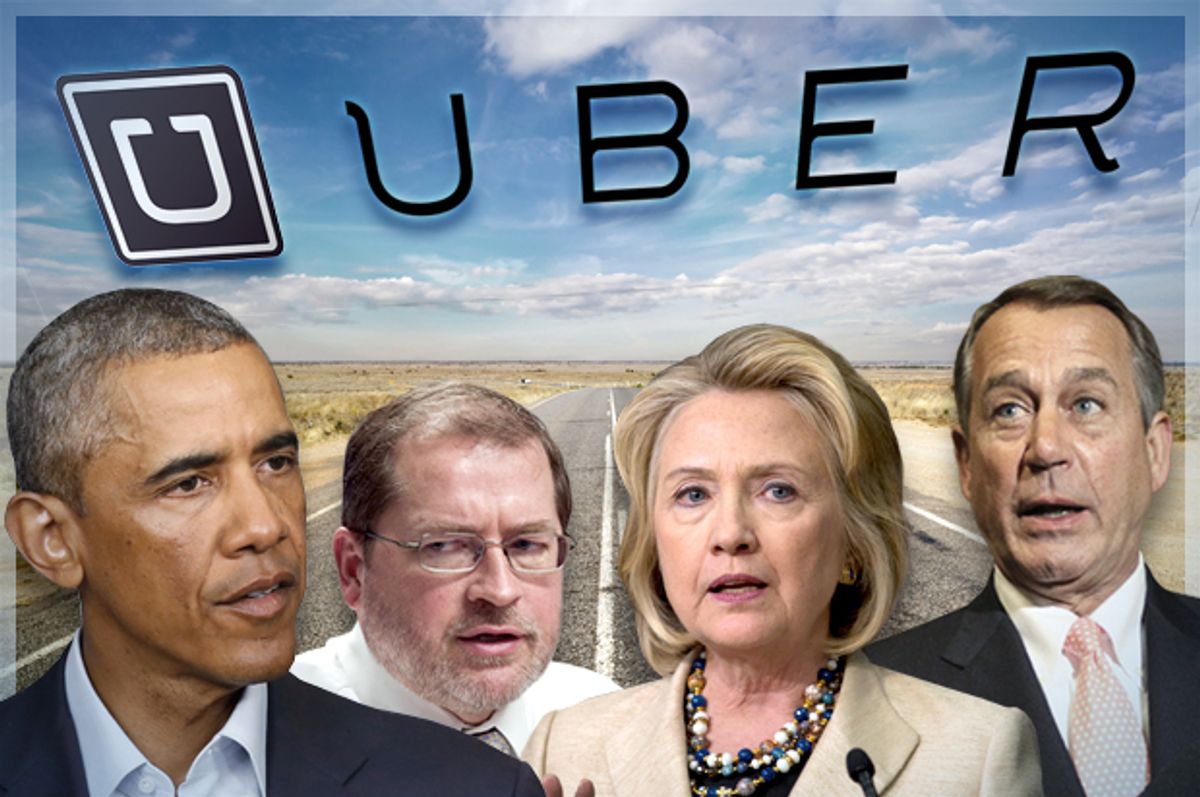

Did Grover Norquist just help Obama 2008 campaign manager David Plouffe get a job with Uber?

In July, the arch-conservative, anti-tax, anti-labor Republican strategist co-authored an opinion piece arguing that Uber could help the GOP "gain control" of U.S. cities. Republican Party leaders promptly embraced the tactic, leading to a wave of stories about "why Republicans are jumping on the Uber bandwagon."

The reasoning was simple: Young people love Uber, but generally don't care for Republicans. So if the GOP can paint Democrats as the regulation-loving bad-guy bureaucrats fighting to stop Uber from expanding toward total world domination, young people will start loving Republicans again.

But the reasoning was also dumb, because, as Emily Badger has pointed out in the Washington Post, numerous elected Democrats across the U.S. support Uber and have been busily passing Uber-friendly legislation. The regulatory battle over exactly how new ride-sharing and ride-hiring services should conform to existing public safety and commercial insurance requirements is a complicated, nuanced and fast-evolving fight that doesn't always map neatly to traditional Democratic/Republican ideological splits.

Worst of all, Norquist's reasoning might also be downright disastrous, because maybe it's not a promising sign for Uber's attempts to mobilize young people if its brand is tarred by an association with rabid arch-conservatives. So Norquist may have unwittingly provided Uber with the incentive to throw lots of money at David Plouffe, who promises to associate Uber with something entirely different -- the youthful exuberance and "progressive" idealism of the coalition that elected Obama in 2008!

In one month, Uber went from Norquistian "drown the government in the bathtub" rhetoric to "yes we can" idealism. You can say a lot of things about Uber, but you certainly can't say the company is boring.

So what are the politics of Uber? Is the Plouffe move, as suggested by Jacob Fischler at BuzzFeed, just one more piece of evidence exposing Obama's top political aides as secret anti-union Republicans? Or is the Norquist-Plouffe intersection proof of an emerging new force in American politics, a mushy libertarian left that is simultaneously progressive on social issues but conservative on labor and regulation?

Maybe the best thing to do is leave old labels out of the game altogether. The politics of Uber, like the politics of so much of Silicon Valley and late capitalism, is a politics where the consumer always comes first. That's a politics that's tough on workers because the laboring classes always take a hit when price and convenience are the highest marketplace values. But it's also a politics that's tough on anti-government bashers. Because consumers want a government that works; they want to be sure that their Uber driver has liability insurance and isn't a repeat drug offender, just like they want clean water and air and fair mortgages. In other words, they simultaneously want a great price, convenience and consumer protection.

Stuff that in your bathtub, Grover Norquist.

* * *

The semiotics of the announcement of David Plouffe's hiring by Uber are fascinating. For example, consider how Plouffe used the word "inexorable" in an interview with the New York Times.

"We're on an inexorable path of progress here," said Plouffe. Which translates as: Uber and the rest of Silicon Valley's innovative disrupters are going to conquer us all in the long run, so we might as well just get used to it and stop throwing roadblocks in their way.

Beware! When a company with a name like "Uber" is associated with "inexorable," resistance is obviously futile. And it's worth recalling, this isn't just about crushing existing taxi "cartels." Uber has made no secret of its ambitions to become a logistical hub that will compete with the likes of UPS and FedEx and Hertz, that will deliver groceries, as well as human beings, more efficiently than any other company. Uber's algorithm is what's inexorable. And an algorithm doesn't boast any particular party identification: It's just there to make consumers happy.

But fast on inexorability's heels comes the issue of what the word "progressive" really means. As Emily Badger reported, John Hickenlooper, the Democratic governor of Colorado, supported Uber's hire by saying that Plouffe will bring the same "progressive approach" to campaigning for Uber as has been demonstrated by Colorado's "embrace of innovation and disruptive technology."

When you pull your phone out of your pocket, click a couple of buttons, send a signal that bounces off a satellite, and a car-for-hire magically appears in front of you in a few minutes, it certainly feels like we are living in an age of technological progress. But the jury is still out on whether this kind of innovation is truly socially progressive. A society that puts consumers first has obvious disadvantages for workers. Silicon Valley and the tech economy have never embraced unions, were pioneers in the exploitation of temporary labor, and actively colluded to keep the wages of even the most highly qualified engineers artificially low, all in the name of providing "disruptive" consumer-friendly services. There's a conservative economic argument that the money that consumers save using Wal-Mart or Amazon or Google or Uber gets invested in other sectors of society, resulting in new jobs and greater prosperity. But that's never been considered a particularly "progressive" argument, at least insofar as that word is understood in contemporary American politics. Progressives tend to favor stronger social safety nets for the people the market leaves behind, and worry a lot about whether technological advances are feeding economic inequality and contributing to downward pressure on wages.

Perhaps most remarkably, in his own statement on his hiring by Uber, Plouffe made a direct comparison between the company and the 2008 campaign:

And when you walk thru Uber’s HQ in San Francisco, the place is pulsating with young, brilliant and dedicated employees who believe they are part of doing something historic and meaningful and won’t take no for an answer. It’s a feeling I’ve been fortunate to experience previously and feel incredibly lucky to be surrounded by that talent and energy one more time.

In 2008, Plouffe mobilized progressives to vote for Obama, in part by promising an expanded safety net. It remains to be seen whether he can mobilize progressives in 2014 to support the business goals of a company that has apparently unlimited access to venture capital and financing.

But it could work, if Plouffe is mindful that the voters he mobilized in 2008 aren't obsessed with price and convenience to the exclusion of all else. Consumers love a great deal, but they also don't want to be endangered or ripped off. Some of them may even be skeptical of the thoroughness with which a private, profit-minded company might perform the task of, say, conducting the proper background checks on drivers. Some of them might also wonder what the future will look like when the existing, tightly regulated taxi companies are gone, and our only choice for a ride is a company that hikes prices way up whenever it rains or snows. The politics of consumerism get pretty complicated when you start thinking hard about what Silicon Valley-style progressivism really means.

Shares