In the wake of the Ferguson shooting, a recent Pew poll finds that 47 percent of whites believe that “race is getting more attention than it deserves,” with regards to the death of Michael Brown, while only 18 percent of African-Americans feel the same. Meanwhile, a similar Pew study found that whites are far less likely to see discrimination in the treatment blacks receive by the education system, the courts and hospitals. Such views are held by many Americans, who believe that “blacks are mostly responsible for their own condition.” Police killings of unarmed blacks are certainly the most visible manifestation of systemic racism, but data show that racism still manifests itself frequently in everyday life.

In America, race determines not just where someone lives and what school he or she attends, it affects the very air we breathe. Although many whites wish to believe we live in a “post-racial” society, race appears not just in overt discrimination but in subtle structural factors. It’s impossible to delineate every way race affects us every day, but a cursory examination of major structural racial problems can give us a feeling for how far we still have to go.

1) Education

Education is an important key to fostering upward mobility and alleviating inequality. However, schools today are becoming more segregated, rather than less segregated. At the peak of integration, 44 percent of black Southern students attended majority white schools. Today, only 23 percent do. This is particularly worrying because recent research by Rucker C. Johnson finds that school desegregation benefited black students, because it “significantly increased both educational and occupational attainments, college quality and adult earnings, reduced the probability of incarceration, and improved adult health status.”

Researchers have increasingly referred to a rise of “apartheid schools,” which are almost entirely non-white. In 2003, one-sixth of all black students were educated in such “apartheid schools.” These districts are underfunded and understaffed, and frequently referred to as “dropout factories.” So students of color are far less likely than their white peers to attend schools with a full range of advanced courses.

As ProPublica documents, more and more schools are squeezing out of court oversight. The result, according to Sam Reardon and his colleagues, is increased racial segregation.

(Source)

At the college level, the situation is little better. A recent report by Anthony Carnevale and Jeff Strohl finds that college education in America consists of “a dual system of racially separate and unequal institutions despite the growing access of minorities to the postsecondary system.” They find that students of color are less likely to end up in the most selective schools than white students with the same qualifications.

2) Wealth

There is a large racial wealth gap between blacks and whites in America, partially driven by income but exacerbated by racially biased housing policies (which will be examined below). A recent research brief by the Institution on Assets and Social Policy finds that the wealth gap between white families and African-Americans has tripled between 1984 and 2009. The recession has only exacerbated the gap, with whites losing 11 percent of their wealth between 2007 and 2010, while blacks lost 31 percent and Hispanics 44 percent.

(Source)

The housing crash disproportionately affected blacks and Hispanics, who were more likely to receive subprime loans even when compared to whites with similar credit scores. In one instance reported by the New York Times, a loan officer at Wells Fargo said the bank “saw the black community as fertile ground for subprime mortgages, as working-class blacks were hungry to be a part of the nation’s home-owning mania.” However, even before the recession, disparities in employment, college education, homeownership and inheritance helped solidify racial wealth gaps. Instead of wealth, more and more Americans, particularly people of color, are burdened with debt.

3) Job Markets

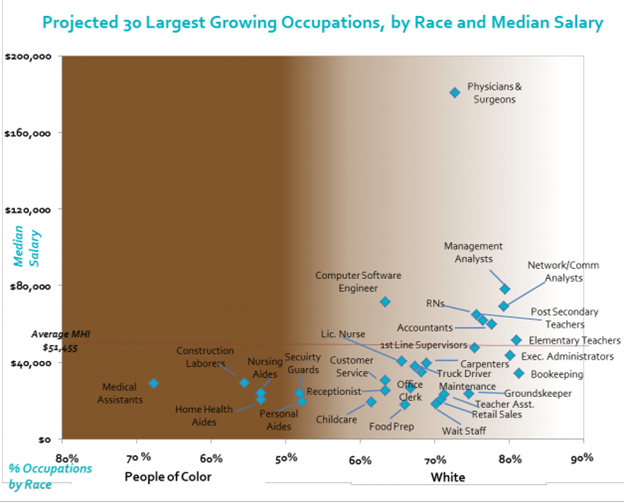

Unemployment is particularly high among African-Americans, the result of both explicit discrimination and occupational segregation.

Occupational segregation, or the delegation of blacks to jobs with low upward mobility and wages, is rife. People of color are primarily affected by practices like just-in-time scheduling, which gives workers little warning before a shift.

Part of the problem is infrastructure and education. People of color are far more likely to rely on public infrastructure, and therefore suffer from cuts to public transportation. Decades of housing segregation have trapped African-Americans in jobless areas with badly understaffed schools. Social networks reinforce the patterns, since most Americans get their jobs through friends and family connections. Outright discrimination plays a role as well: Marianne Bertrand finds that applicants with white-sounding names are 50 percent more likely to receive a call-back than applicants with black-sounding names with the same credentials.

4) Upward Mobility

Possibly the defining American attribute is the dream of upward mobility. Sadly, this tends to be more farce that fact -- America lags behind other developed countries in measures of upward mobility. But recent research by Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, Emmanuel Saez, shows that levels of upward mobility vary across the country -- and is strongly predicted by income inequality and racial segregation. They write: “Income mobility is significantly lower in areas with large African-American populations.” (Whites in the areas also had lower levels of mobility.)

Specifically, they note the importance of segregation, “areas that are more residentially segregated by race and income have lower levels of mobility.”

(Source)

A recent Pew Research Center study shows that not only do blacks have lower levels of upward mobility; among those that do make it into the middle class, their children are more likely to slide back into poverty. In what may be the most depressing footnote I’ve ever seen in a chart, Pew notes that there are not enough observations of blacks in the fourth and fifth (read: highest) quintiles of income to make observations about upward mobility.

(Source)

In a recent study, Bhashkar Mazumber finds that out of all children born between the late 1950s and early 1980s, 50 percent of black children born into the bottom 20 percent of the income scale remained in the same position, while only 26 percent of white children born into the bottom 20 percent of the income scale remained in the same position. He also finds, like Pew, that African-Americans in the middle class are on far more precarious footing than whites: 60 percent of black children born in the top half of the income distribution fell to the bottom half later in life, but only 36 percent of white children born in the top half of the income distribution fell to the bottom half later in life.

Surprisingly, Mazumber finds that “[w]hile these results are provocative, they stand in contrast to other epochs in which blacks have made steady progress in reducing racial differentials.” While we like to believe we are constantly progressing, these data suggest we may be backsliding with regard to mobility and race.

5) The War on Drugs

The socioeconomic realities discussed above cannot be divorced from the war on drugs: It is a war that is primarily fought against people of color in the country. One in 12 working-age African-American men is incarcerated; and while whites and blacks use and sell drugs at similar rates, African-Americans comprise 74 percent of those imprisoned for drug possession.

The U.S. prison population grew by 700 percent between 1970 and 2005, while the general population grew only 44 percent. According to the Bureau of Justice statistics, around half of federal prisoners’ most serious offense is drug-related. The war on drugs has undermined the legitimacy of law enforcement and eroded their esteem in the eyes of the public. Even before the Ferguson shooting, 70 percent of blacks agreed that, “blacks in their community are treated less fairly than whites” when dealing with the police.

Instead of housing those who have committed violent crimes, U.S. prisons are increasingly teeming with nonviolent offenders. Formerly incarcerated people struggle to find work, and are therefore more likely to turn to crime in the future, creating a vicious and counterproductive cycle. A Pew study finds that the costs of incarceration are often hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost wages. Even when they are no longer incarcerated, former inmates are often deprived of basic rights, including franchise. Around 13 percent of African-American men have been denied the right to vote.

This is to barely touch on the empirical literature on school punishment, access to healthcare, a history of racially biased federal policy and the other deep issues that we face. The most disturbing fact is that in almost all of these areas, we have actually seen previous progress eroded, even while we proclaim ourselves a post-racial society. It’s time to take an honest look at race in America. We probably won’t enjoy it. But we need it.

Shares