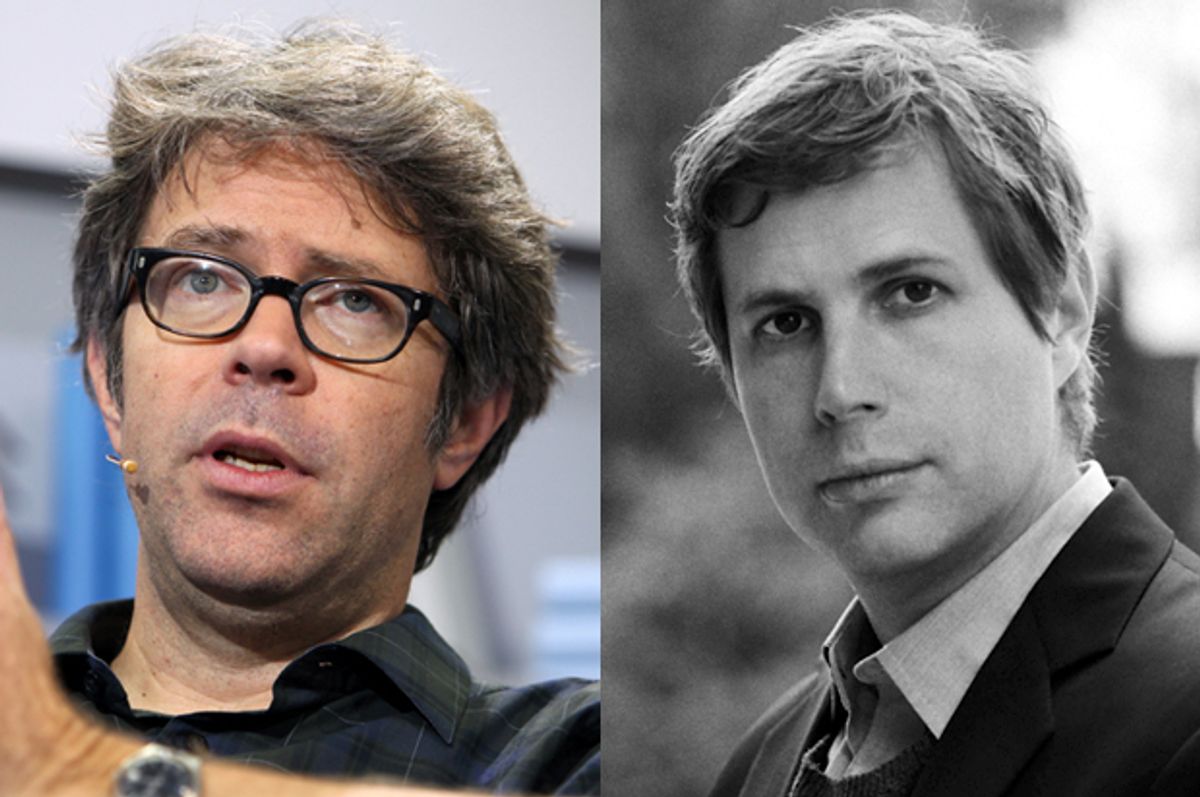

I met Daniel Kehlmann in Vienna in 2005, on the night before German sales of his novel "Measuring the World" went ballistic. He was ridiculously young, ridiculously well read for being so young, and ridiculously nice. He soon became a good friend (later also a collaborator on a translation project of mine), and it's been a pleasure, over the past nine years, to see him further blossom as a storyteller. In his collection of linked stories, "Fame" (published in 2010 in the U.S.), and even more in his new novel, "F," Daniel has become the go-to guy in Central Europe for engagement with the weirdness of the postmodern world we inhabit.

What follows is an edited transcript of a conversation he and I had by phone last month.

Jonathan Franzen: I want to start by saying I’m a big fan of this book. It may be my favorite thing of yours yet, although I’m also a huge fan of "Fame." It seems like this is a novel about a genuinely serious philosophical question — why our life takes the particular path it does — and about the weirdness of being inside a life while it’s taking the turns it does. But for me the actual experience of reading the book was page after page of comedy. One of the three brothers at the center of it is this grossly overweight priest who can’t stop eating and doesn’t believe in God. Another one is an investment banker who’s trying to conceal from everyone in his life that his business is going down in flames – another classic comic situation. And then you have the third brother working as an art forger in the art world, which is a pretentious and phony place where people are doing pretentious and phony and craven things. It’s all just really, really funny. So my first question would be: Are you comfortable with being called a comic novelist?

Daniel Kehlmann: Yes, I am. I published my first novel when I was 22. It is a very serious book. I was one of these writers who feel that the funny and playful part of their personality is the part they should leave out of the books because literature is serious business. It took me a while to understand that if in life I like to laugh about things, then I should try to get that side of myself into the books. It took me a while to learn how to work with comic effects.

It seems like you’re definitely further in that direction, because this is your funniest book yet. I wonder if that creates difficulties for you in Germany. The stereotype from the U.S. is that Germans are extremely serious. Even here, if you put the word "comic" in front of the word "novelist" — it’s just what you say. Comic is the opposite of serious, and I have a feeling it’s even more that way in Germany. Correct me if I’m wrong.

"Measuring the World“ was a comic novel about classical German culture, and that’s how reviewers around the world saw it right away, but it was not considered a comic novel in Germany when it came out. Detecting humor is not our strong side.

It’s crazy. It’s right there in front of them. The first thing I put in every email to my German editor about my own fiction is “try to remember that this is supposed to be funny.”

Germans and humor -- it’s a complex problem. There are some very good comic writers in Germany, but German culture has a neurotic relationship with humor.

If I had an extra five hours in my day, I’d be translating some of Thomas Brussig’s novels into English. He’s hilarious and I think it’s a tough sell on both sides of the water.

A writer like Brussig has a real problem in Germany, because he is all about comic situations.

And he’s laughing at a totalitarian regime.

And he does it in such a wonderful way. He should be much more widely read.

And he’s unknown here. But let’s get back to you. You had your mega-success — the thing that made you practically a household name in Germany with "Measuring the World" -- and I understand you’re working on another historical novel or a novel set in the historical past.

I’m thinking about it. I haven’t decided yet, but I’m definitely thinking about it.

Well, for the purposes of my question, let’s assume that there are two distinct strains of Kehlmann literary production. One of them is this very lively intellectual engagement with the historical past and the other is this extremely modern strain — a realism of the here and now, or a near-realism. Sometimes you diverge into a kind of crazy hyper-realism or half-realism. But the feel of those two strains is really very different. You’re funny in both veins, and philosophically serious. And yet —

What surprises me is how our point of view is always framed by the historical situation we’re in. We are captives of history, and most of the time we don’t even notice. We behave in very strange ways, and the things around us are extremely weird, but just because we’re used to them, we think everything around us is just normal the way it is. Looking back in time I am fascinated by how extremely different people lived and thought -- and I don’t mean back in the stone age, I mean quite recently. You only need six generations to arrive at people who saw Napoleon riding by on the street. Just six! So on one hand, I’m trying to understand the extreme strangeness of what life was like a short while ago, and on the other hand I try to capture the weirdness of the historical moment we live in right now. That concerned me very much when I wrote "Fame": how much our life changed when mobile phones arrived. And just a little while later we didn’t look back or even notice that change anymore.

Well, if I can paraphrase, it’s as if you’re always writing historical fiction and quite a bit of it happens to be set in this historical moment …

Yes, thank you. That makes sense.

Your new book isn’t just about this very recognizable, weird world we live in. There’s also, running through it, the strange little thing you’re doing with the succeeding generations. You made a very distinct and strong formal move in incorporating that into the book. These people 600 years ago who live and die in a sentence or two. And that’s probably what’s so haunting about the book. It seems to me as if, in a way, you’re decentering us from our natural sense of “we’re the center of everything.” And what you do with those passages in the book, where you’re harking back to much earlier centuries — again, very briefly and elegantly — is part of the decentering process.

That whole chapter started out completely different. I wanted to write a short, funny parody of the information overkill of many family novels where you get all this information about grandparents and uncles and aunts, and actually you just want to get back to the main characters. But then the chapter became darker and darker. It’s the darkest thing I’ve ever written.

The juxtaposition of that very, very dark thing — history is a dark thing — with the long stretches of really Apollonian humor is part of what makes the book so wonderful.

I am so glad to hear that! This contrast is what I was going for.

Worked for me, Daniel. And it gives the book the weight it has. I mean, there are these really basic questions that we just don’t pay attention to and I think it’s brave — because they’re such basic questions that I think it’s brave whenever a novelist takes them on. It’s like, oh, yes, people have been wondering about, you know, what is the meaning of life [laughs] and why do we have the lives we have — people have been asking these questions for millennia and I applaud you taking them on, and I think it works. At the same time, moving on to another question, is it accurate to say that this is your first real family novel?

Yes, it is -- in a certain way. "Family” is quite a big word, so in the case of my novel only the first letter remained. When I started out I thought: “I want to do to the family novel something similar to what I did to the historical novel when I wrote 'Measuring the World.'” Which is to write an unusual specimen of the form. A family novel for people who don’t trust family novels.

That is what to the American eye seems Central European about all your work. We Americans tend to be much more conventional formally, even our serious novelists. To me, part of the excitement of reading your work is that these are incredibly accessible books — it’s not a chore to read them, it’s the opposite of a chore — and yet there’s this willingness to be experimental. “F” is absolutely not like other family novels.

I’m going to say this not to return the compliment, but just because it’s true: Years ago "The Corrections" came as a real revelation to me. That novel showed me that we have to take everything experimental literature has taught us, and then with these tools, try to create complex, lively characters. And this is what I have tried to do ever since.

I think particularly successfully in this book. The three brothers are wonderfully drawn and very distinctly drawn. And are also quite movingly tender with each other. It’s a fractured family but not what you would call a dysfunctional family, I don’t think.

And one of the brothers — Ivan — is a genuinely good person. That’s also something I had never tried before. Dostoyevsky once said the hardest thing to create is a good person. I often think of that.

So in your first venture into family fiction, I’m wondering if there were new or unexpected kinds of meaning to this that you found available when you brought brothers and a father - -and significantly also a daughter -- into the mix?

I’m glad you mention the daughter. Most people only talk about the brothers.

Oh, but the daughter is key.

She is key to me too. I wouldn’t say she is a female voice, she is rather a child’s voice -- but a very distinct voice, quite different from the others. The novel would not work without her. About the concept of family: When you write about siblings it gives you the opportunity to give them different professions, to send them out into different social worlds. You don’t have to do that, but if you don’t you might miss out on a great opportunity.

Siblings typically differentiate themselves by choosing different fields. There’s a kind of family where everyone is an FBI agent, but the classic family is one where one sibling is an artist and one is a teacher and so forth. The family in itself makes the world seem fuller.

I had never before consciously written about social milieus. So this was a challenge I set for myself. I don’t have siblings myself, my experience was always that of being an only child and wanting brothers or sisters. I think most people who grow up with siblings want to be an only child or at least imagine what it would be like to be alone with their parents, whereas I always imagined what my brothers or sisters would be like. But I never experienced the real-life complications of brotherhood.

That’s one of the ways in which it’s not a conventional family novel. It’s not so much about the sibling dynamics; it’s about this sense of connection, this sense of an original whole that has been broken up into this multifaceted thing. I mean, it is a philosophical novel, and I hesitate to use that word, because it sounds like, Oh, scary-boring alert! But philosophy is not supposed to be boring or scary when it’s done well.

What’s really boring is symbolism. It’s very important to stay away from that. When you write about a father who leaves his children, you should stick with your characters and absolutely stay away from any association that the father could be God or Truth or whatever. That would be horrible. But symbols are very different from ideas. Questions like, "Do we actually have a fate?" or "Do the things that happen to us have a meaning or not? And if they don’t, how can we live with that knowledge, or do we actually have to invent meaning?" -- these questions are very real, they touch the substance of everything we do in our lives.

Right, and then, of course, the trick for the philosophical novel is to give those questions dramatic form, so they’re not posed as questions, they’re questions that arise.

Traditionally the term "philosophical novel“ meant writing a novel to support a theory the writer formed before he or she started writing, and usually that’s terrible. That just doesn’t work with our modern notion of what a novel should be like. Novels are all about ambivalence.

Coming back to the way in which the family creates a multifaceted thing, the social planes do intersect, but they’re at angles to each other. You have the monied world of Eric, and you have the comic world of being a parish priest, and then you have the art world in Ivan’s. There’s a Rubik’s Cube on the cover of the American edition, correct? Or did that get changed?

That got changed. I really liked that Rubik’s Cube, but it got changed.

That’s too bad. The image of the cube — you can only see three sides at once — seems very much in keeping with the feeling that you’re getting these three different social planes. But it also connects with the experience I had reading the book: "Whoa! I have no idea where this is going!" It’s these crazy stories that suddenly, in the last quarter of the book, begin to click into place in ways that you don’t see coming but nonetheless make a certain kind of sense. It all fits together, like the last twists of a Rubik’s cube. Not in a reductive way but in the sense of, “OK. Now I see why we’ve been getting these different stories." And it makes me wonder: Did you have it all planned out from the beginning?

It was actually the first time I didn’t plan out anything in advance. The only thing I knew is that I wanted to write about three brothers, and that they all should be forgers or frauds, in different ways. And then I did something I’d never done before: I wanted to find out how the characters would develop and what would happen to them. It took me many false starts and new attempts and rewrites to find out who these people actually were. I didn’t plan much about the structure, all that was just happening. For example, the lunch Martin has with his brother Eric, where you get one side and then, much later, you get the other side: The novel comes back to that moment to narrate it from the other brother’s point of view, and that’s when you find out that everything Martin assumed about his brother was wrong. So now it seems like that was all planned out beforehand, but the truth is I was quite surprised myself. What I did know in advance is that I wanted something terrible to happen to one of the brothers, something that felt unexpected and ultimately meaningless. That’s a very difficult thing to do, as in fiction nothing can ever be truly accidental, because whatever happens you know there is a writer out there inventing it. A character in a novel has a destiny -- per definition. So one of the most difficult things is to have something happen in a novel that has the feel of a real accident. It’s quite hard to pull off, maybe it’s not even possible.

And you suddenly find yourself sort of answering the question you set out to ask.

In a certain way, yes. I mean, I still don’t think a novel can give a real answer to the big questions like the question of fate, but in a way the structure of the novel is the answer. But it’s an answer I can’t quite spell out.

Right, well, that’s the glory of literature, in my view. It’s also why the real philosophers don’t trust literature.

They think it’s too easy. You should have an answer spelled out, and they are right in their way, but we storytellers are also right.

I was shocked when "Fame," which was your last book in the U.S., didn’t get more critical attention. You were coming off this gigantic international bestseller, and here was this collection of stories, all of them extremely well made, some of them super-funny, and all of them really interesting, I think, to an American audience. As an American reader, I had this sense of totally recognizing the modern world in which they were taking place, but they were also not American. It was like, "Oh, so there’s a central European version of this weird historical place we’re in." And it was a very accessible book, and yet nobody I know has read it, except for our friends, our mutual friends. And they had to.

They had no choice.

So, well, I know it’s risky for novelists to talk about their critical reception. But I’m wondering if you want to tell me how you feel about your own reception, both here and in Germany. And if there’s a significant difference between the two critical establishments.

I have been very lucky, because many people read my books in Germany, France, Italy and some other countries. It’s the best thing that can happen to a novelist -- to be able to make a living from writing. But I’m also in a weird position because the German literary establishment tends to dislike me because they think I’m so widely successful internationally, which is, of course, just a projection.

You're tiling your bathroom with gold bricks.

I’m "world famous“ only in Germany. But when it comes to the U.S., it is still extremely difficult to be a novelist not writing in English. I’ll never forget the radio host who asked me on my American book tour with genuine incredulity: “So is it true that this book was actually not written in English?” Americans feel that there is something absurd to the idea of not being American. Any young writer from Brooklyn who writes about the Holocaust gets a lot of attention, whereas a true genius like Imre Kertész, who even got a Nobel Prize and arguably wrote the best Holocaust novel in the history of literature, doesn’t get much attention in the U.S. Something that really made me angry about the American reviews of "The Kraus Project," by the way -- I know you don’t read reviews, but I actually did read them -- was how many of them treated Karl Kraus, who is one of the major European writers of the 20th century and whose play about the First World War you can still see all over European theaters, like some completely unknown, arcane, shady figure. America has a such a vibrant literary culture, but it also has a deeply parochial side.

I know you’re Austrian, not German --

I have both passports.

And you’re all but married to a German and you have a German citizen for a little boy, and you write in German, and so, well, you pretty much count as a German to Americans. And it seems to me that it’s about time people paid some attention to Germany because Germany basically rules Europe now.

It’s not a thought I particularly like. But it’s true. Or maybe not entirely so. My girlfriend left Germany in 1992 and has been living in New York ever since. My little boy is waiting for his American citizenship. And Germany is still entirely interdependent with America, so much so that a free trade zone seems imminent and will bring us even closer. But you’re right, Germany seems quite powerful again, and I am not even sure how it happened.

It happened financially. The Germans have taken over again, but in a somewhat nicer way. They send bankers now, not tanks. And I can’t help feeling there should be more interest in it. Somebody like you, who’s young and who’s technologically hip and isn’t writing about life in 1870 or something, you’re writing about life in 2014 — I can’t help thinking that your time has to be coming, and that what you’re doing in these novels about a contemporary Central Europe ought to be interesting, especially because they’re so fun to read. But I wonder, do you think of yourself now as more of a cosmopolitan author than as a German-language author? Are you looking to your German contemporaries, or are you looking more overseas?

I always looked more to North and South American than to contemporary German literature. For a long time I felt more like a cosmopolitan than like a German writer. But recently I rediscovered some Austrian writers, I rediscovered the rich Austrian tradition that also formed me. So now I feel slightly less cosmopolitan than I felt a few years ago. Is that a good thing? I don’t know.

You’ve taken your place in the comic tradition of Austrian writing.

Well, if you write in German and if you spend a lot of time in Germany then it’s certainly helpful to remind yourself of the fact that there’s also Austria, there’s also a cultural tradition within the German language that’s deeply humorous and also quite bleak. I think it’s important to have some kind of local connection. To have some kind of tradition in which you grew up and to which you stay connected. And that will always be the German-Austrian tradition for me, and I don’t think I will ever let go of that.

Right, I’m with you. It’s kind of an axiom of contemporary anthropology that you have this globalizing monoculture but it takes on a different favor in Brazil than it does in Houston, a different form in Berlin than it does in London.

And it’s one of the true advantages of traveling that you learn about the power of local traditions. People who don’t travel tend to think that in these globalized times the world is the same everywhere -- whereas my experience is the more you’re traveling and the better you get to know people in different parts of the world, you learn to appreciate how big the differences are. And it’s the same with history. Of course human beings were in some core always the same, but that’s actually quite banal. The more interesting truth is that human beings are extremely different, and they adapt very quickly, and they keep changing constantly.

Shares