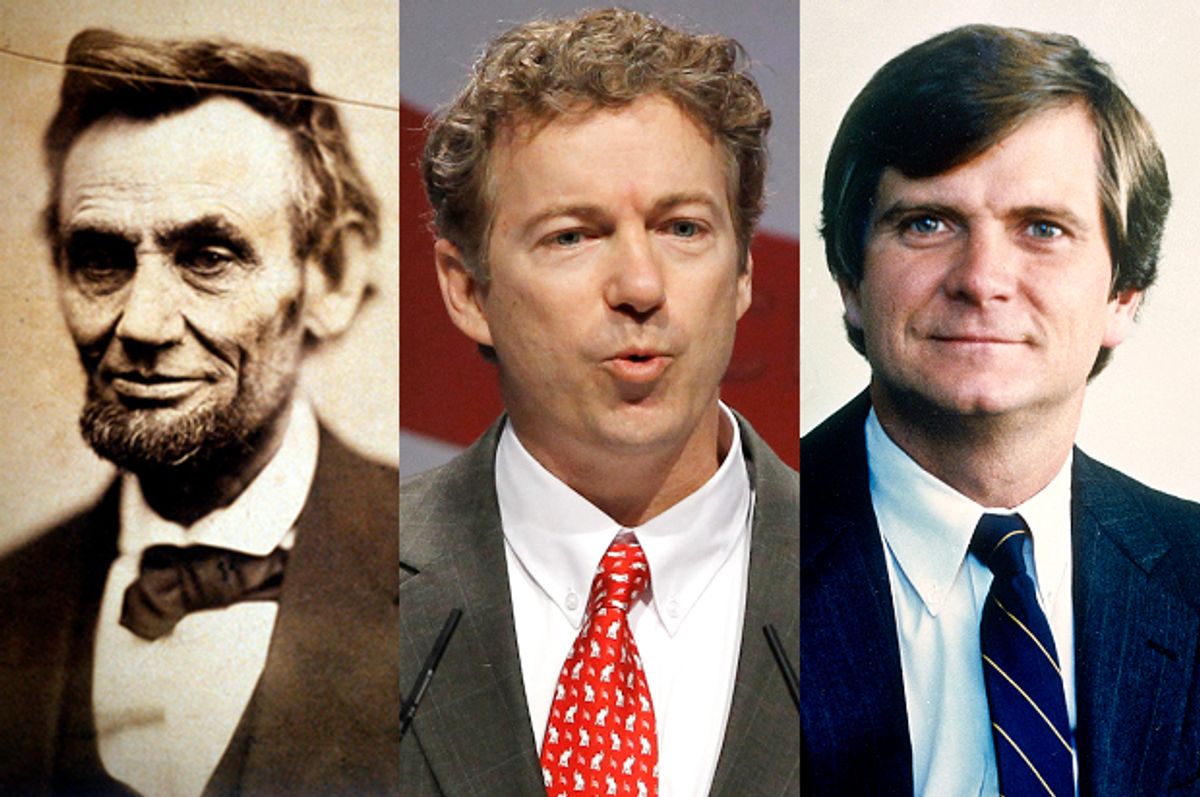

Founding the Republican Party

The political party that grew from these concerns over slavery was the Republican Party. In turn, it nourished and carried forward the public’s anti-slavery feelings. But the party was an amalgam of strangely different elements. It contained men from different political backgrounds, and it combined antislavery convictions and antiblack prejudices.

“He was more nearly the founder of the Republican Party than any other one man.” So declared Alexander K. McClure, the well-connected Pennsylvania journalist and politician, in regard to Francis Preston Blair. This grand old man of Washington politics, father of Postmaster General Montgomery Blair and Congressman and General Frank Blair, had far-reaching influence. With his sons, he played a key role in the Lincoln White House. Lincoln’s Illinois friend and bodyguard, Ward Lamon, said, “Between Francis P. Blair and Mr. Lincoln there existed from the first to last a confidential relationship as close as that maintained by Mr. Lincoln with any other man. To Mr. Blair he almost habitually revealed himself upon delicate and grave subjects more freely than to any other.” When facing “an important but difficult plan, he was almost certain . . . to try it by the touchstone of Mr. Blair’s fertile and acute mind.”

Both Lincoln and Blair came originally from Kentucky. That common bond gave them a feeling of kinship toward each other and toward Southerners. But their party backgrounds were different, mirroring the diversity in the newly formed Republican organization. Lincoln had followed and admired the great Whig leader Henry Clay. Francis Preston Blair, older by eighteen years, had been devoted to Old Hickory, the Democratic president Andrew Jackson, and his political ideology.

Blair first made his name and career supporting Jackson in the nation’s capital. As a close friend of the president, he laid the basis for his fortune by publishing a pro-administration newspaper, the Globe. Blair shared Jackson’s hostility to the Bank of the United States and to any aristocratic concentration of power. While favoring states’ rights and a limited central government, he also agreed passionately with Old Hickory that the Union must be defended against Southern threats. Soon Blair launched another business, publishing the debates of Congress in the Congressional Globe. By the time he turned the Congressional Globe over to others, he had amassed great wealth and influence.

Blair “retired” to a beautiful home and country retreat in nearby Maryland. Charmed by a spring whose waters carried shiny flecks of mica, Blair bought up the surrounding land. There he built an elegant home, created a small artificial lake, and decorated his grounds with statuary and honeysuckle. “Silver Spring” welcomed a wide range of prominent visitors from the nation’s capital. In this way Blair’s homestead supported and magnified the remarkable talent he possessed for forging friendships with political leaders. Charles Sumner and President Lincoln were among the many who enjoyed the beauty and restfulness of Blair’s creation.

Politically, however, Francis Preston Blair never retired. Through the 1840s he stayed in close contact with leaders of the Northern Democracy, many of whose members were growing impatient with Southern demands and Southern control, all focused on the extension of slavery. That feeling burst into the open in 1846. A Pennsylvania Democrat, David Wilmot, broke with his party’s president, James K. Polk, to offer his famous proviso. The Wilmot Proviso bluntly declared that slavery should not be allowed into any lands gained through the war with Mexico. Leaders of the slaveholding South repeatedly blocked the proviso in the U.S. Senate, but the legislatures of fourteen Northern states endorsed it. The Blairs were part of this growing movement toward “free soil.”

In 1848 Blair threw his support to the new Free Soil Party. Though he owned slaves, he believed, like the Founding Fathers, that slavery was a social and political evil that should someday end. “Bold, defiant, adroit, and vitriolic,” Blair argued that slavery must not expand. The Free Soil Party could further that mission. To former president Martin Van Buren, who agreed to be the new party’s candidate, Blair wrote, “To my mind, this appears the greatest act of your life.” The new party won 10 percent of the vote, and Blair pressed Northern antislavery Democrats to become more aggressive.

In the 1850s battles over the admission of California to the Union, a stronger fugitive slave law, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act further inflamed controversy. By the beginning of 1856 a variety of Northern antislavery forces were ready to unite in a new party. The newly minted Republican Party had its founding convention in Pittsburg. There delegates chose Francis Preston Blair as permanent president of the proceedings. They also named him to the convention’s Committee on Resolutions and Address and placed him on the National Executive Committee.

The senior Blair published a letter identifying the Republicans with Andrew Jackson’s love of the Union. He also blasted the “sinister designs of the nullifiers of the South” and laid out a history of efforts by the slave interests to gain “extended dominion.” For the party’s candidate he favored John C. Frémont, a celebrated former army officer who had explored the West with Kit Carson. Thanks to Blair’s influential support, Frémont won the nomination. The older man’s insight that the Pathfinder could win Northern and western votes proved correct. The new Republican Party won one-third of the popular vote in 1856.

Blair’s sons also pioneered as free-soilers and Republicans. During the 1850s Montgomery and Frank added energy and substance to the cause of antislavery and to the new party. Both men had moved to Missouri, where they became active in politics. They relied on the law, which they had studied at Transylvania University, as the basis of their professional careers. Montgomery became a judge in St. Louis and served as U.S. district attorney for four years. In 1850 he joined others in Missouri who condemned slavery’s influence on whites. To allow slavery to expand would be “neither honest nor democratic,” he said. The South’s so-called peculiar institution retards “growth and prosperity . . . impairs enterprise . . . paralyzes the industry of a people and impedes the diffusion of knowledge.” Other evils of slavery were its encouragement of “aristocratic tendencies and the degradation which it attaches to labor.” As for the territories, they must be held “in trust for unborn millions” as a free-soil legacy. These views were common currency to all in the Blair family. Though they held slaves, they were critical of the institution, adamant against its expansion, and enthusiastic about colonization of blacks abroad. Defenders of the Union and foes of Southern domination, they also revered states’ rights and a limited federal government.

About this time Montgomery resigned his position as judge in order to earn more money. He declined a seat on the Missouri Supreme Court for the same reason. It was a sound financial decision. He developed a busy and “lucrative” practice before he answered his father’s invitation to come to Washington in 1853. Installed in the family’s mansion (later known as Blair House) across the street from the White House, Montgomery developed an extensive practice before the Supreme Court. By 1856 he was preparing briefs and arguments in Dred Scott’s suit for liberty. He took this case, which would prove so important to the Republican Party, without a fee. Such service to antislavery won the respect of Abraham Lincoln.

Frank, or Francis Preston Blair Jr., was the younger brother. A superior orator, the family hoped that Frank might become president someday. After practicing law in St. Louis, he fought in the war with Mexico and then became attorney general of the New Mexico Territory. Returning to Missouri, he won election to the state House of Representatives as a Free-Soiler in 1852. By 1856 he was running successfully for Congress as a Republican—the first Republican elected from a slave state. Energetic and determined, he used his powers as a public speaker to aid Frémont and many Republican candidates.

One of those recruits to the new party was Abraham Lincoln, in nearby Illinois. Frank Blair and Lincoln coordinated their thoughts on party strategy, and in the fall of 1856 they arranged to have a St. Louis newspaper, the Missouri Democrat, become a Republican paper. With its large circulation in southern Illinois, the paper could aid both the party and Lincoln’s political aspirations. Before taking his seat in Congress in 1857, Frank went to Illinois to confer with Lincoln. One result of their meeting was favorable coverage by the pro-Blair paper of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Such cooperation would grow and deepen.

* * *

Abraham Lincoln's prominence in the Republican Party came a bit later than the Blairs’. Lincoln had been a Whig, not a Democrat. Following Henry Clay’s example, he was more interested in promoting commerce and banking than in Andrew Jackson’s opposition to concentrated wealth and power. As a state legislator, first elected in 1834, his most notable achievement—moving the state capital to Springfield—came through support for a wildly ambitious plan for internal improvements. Funded by bonds, this plan was so unrealistic that within a few years Illinois owed eight times as much in annual interest as it received in revenue. Payments had to be suspended, the state’s credit was damaged, and the final payments were not made until 1880.

As a young politician, Lincoln engaged in the race-baiting and racist rhetoric that was common among Illinois politicians. While his party’s newspaper, the Sangamo Journal, accused a Democratic presidential nominee of “love for free negroes,” the young Lincoln charged that his “very trail might be followed by scattered bunches of Nigger wool.” His skills as a storyteller also drew on a deep repertoire of racist jokes; moral growth and a greater human sympathy were not evident before the mid-1850s. But Lincoln did signal an early disapproval of slavery, in principle. With only one other state legislator, he issued a protest in 1837 that “slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy.” To balance this position their statement added that “the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than to abate its evils.”

Elected to Congress in 1846 for a single term, Lincoln was a loyal and partisan Whig. His “spot” resolutions attacked Democratic president Polk by demanding to know whether Polk had provoked war with Mexico by sending troops to a spot in Mexican territory. But Lincoln’s education in antislavery ideas also made some progress. He introduced a bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. This proposal involved gradual, compensated emancipation that would not take place without the approval of the district’s residents. Nor would slaves outside Washington be able to gain their liberty by fleeing into the district. Freed slave children would have to serve an apprenticeship before they reached adulthood. As a campaigner for Republican candidates, Lincoln met men like New York’s William Seward and Hannibal Hamlin of Maine who were more outspoken against slavery than he. The influential editor of the New York Tribune, Horace Greeley, categorized Congressman Lincoln as “one of the very mildest type of Wilmot Proviso Whigs from the free States.”

What galvanized Lincoln as an antislavery leader, and turned him toward the Republican Party, was the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. After several years outside politics, practicing law, he now emerged as an eloquent opponent of the expansion of slavery. Illinois’s senator Stephen Douglas had bowed to Southern demands in order to pass this law. It repealed that portion of the Missouri Compromise that prohibited slavery north of 36 degrees, 30 minutes. Throughout the North the Kansas-Nebraska Act alarmed and outraged both black and white citizens. A regional conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Church denounced the act as “wicked and cruel.” An eloquent congressional protest, dubbed “The Appeal of the Independent Democrats,” condemned the opening to slavery of land that had been dedicated to freedom. When Douglas returned to Illinois to defend his law, he ruefully noted that he could have made the trip at night by the light of his burning effigies. His chief critic in Illinois was Abraham Lincoln.

Speaking in Peoria, Lincoln attacked slavery in the abstract and for the effect its extension would have on white people. He showed that slavery clashed with the nation’s ideals while he carefully and adroitly avoided a defense of racial equality.

Lincoln began with Thomas Jefferson. The author of the Declaration of Independence had originated “the policy of prohibiting slavery in new territory.” In 1784 Jefferson drafted an ordinance banning slavery in western lands claimed by the original states. This wise policy, unfortunately, had now been abandoned. The new law concealed a “covert real zeal for the spread of slavery,” and that “I can not but hate,” said Lincoln. He hated it because of “the monstrous injustice of slavery itself ” and because it robbed “our republican example of its just influence in the world.” Extending slavery made hypocrites of liberty-loving Americans. It forced them into “open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty.”

Lincoln’s words about African Americans were carefully crafted. Their presence in the nation was a problem. His “first impulse” would be to free them and “send them to Liberia,” but that could not be done quickly. He doubted that freeing them to be “underlings” improved their condition. However, it was impossible to “free them, and make them socially and politically our equals. My own feelings will not admit of this,” nor would the feelings of “the great mass of white people.” Still, when Lincoln turned to Douglas’s theory of self-government in the territories, he indirectly argued for the slave’s humanity. Whether “the doctrine of self-government is right

depends upon whether the negro is not or is a man. If he is not a man, why in that case, he who is a man may, as a matter of self-government, do just as he pleases with him. But if the negro is a man, is it not to that extent, a total destruction of self-government, to say that he too shall not govern himself ? When the white man governs himself that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government—that is despotism. If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that “all men are created equal;” and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.

Quoting the Declaration of Independence, Lincoln then made a careful choice of emphasis. After repeating familiar words about the “self-evident” truths that “all men are created equal” and have “certain inalienable rights,” Lincoln placed his stress on the next sentence about governments. To secure their rights, men created governments “deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” Instead of equality, which most whites rejected, he focused on the principle of consent.

Continuing an efficient dissection of Douglas’s policy, Lincoln specifically defended the self-interests of white people. “The whole nation,” he insisted, “is interested that the best use shall be made of these territories. We want them for the homes of free white people.” Allowing slavery into Kansas and Nebraska would ruin those territories for white men seeking opportunity. “Poor white people” remove themselves “from” slave states. “The nation needs these territories” as “places for poor people to go to and better their condition.”

It was bad enough, Lincoln added, that under the Constitution slave states gained extra representation—“five slaves are counted as being equal to three whites.” Thus South Carolina, with half the white population of Maine, enjoyed the same number of representatives in Congress. Every voter in a slave state “has more legal power” than a voter in a free state. This provision was part of the original Constitution and had to be accepted, Lincoln said, but he “respectfully” objected to allowing “the same degrading terms” to apply to new states.

The Peoria speech was so potent on various levels that it identified Lincoln as a coming figure in the free-soil movement. With politics in flux, he initially hesitated, watching the Whig Party disintegrate while the anti-immigrant American Party flashed briefly into prominence. But by 1856 Lincoln had declared himself a Republican. His gift for incisive but careful arguments soon made him the leading Republican in Illinois and a man to watch beyond his state.

* * *

A very different man from far-off Massachusetts had aided Lincoln’s emergence in 1854. Charles Sumner helped stir the outrage over Kansas- Nebraska. He was one of three politicians who created the “Appeal of the Independent Democrats.” After Joshua Giddings and Salmon Chase drafted this manifesto, Sumner polished the prose that awakened the North. It was difficult to imagine a Republican further removed from Lincoln in personality and background.

Born into a respectable but second-rank Boston family, Charles Sumner soon established himself in the intellectual and cultural elite of New England. Whereas Lincoln was a self-taught frontiersman, Sumner graduated from Harvard College and Harvard Law School. He then became a protégé of Judge William Story. After publishing learned articles and teaching occasionally at Harvard, Sumner interrupted his growing legal practice to go to Europe. In a year and a half of travel, he managed to meet leading figures in all the major European nations and later entertained them when they visited the United States. Ignoring the moneymaking aspects of law, Sumner turned his energies increasingly to various reforms.

Whereas Lincoln was humble and down-to-earth, a storyteller with the common touch, Sumner was formal and serious, incurably pedantic, and totally lacking in a sense of humor. Terrified of women as a young man, he made influential male friends such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. His connection with Samuel Gridley Howe soon led Sumner into reform. As he boldly criticized society, Sumner offended conservative elements of Boston’s elite. Taking up the cause of prison reform, he used intemperate language against his foes. This won respect from the more advanced reformers but cost Sumner the backing of respectable Boston Brahmins. Seeing himself as a badly treated but virtuous individual, he became more extreme and more convinced that he was right.

Opposition to the war with Mexico moved Sumner into the antislavery politics of the Conscience Whigs. Soon he participated prominently in the formation of the Free-Soil Party. With “one of the most effective speeches” of a lifetime of speech making, Sumner helped launch Massachusetts’s free-soil coalition. Ostracized by most of the elite, Sumner presented himself as the idealist in politics and ran unsuccessfully for Congress. At the same time, a pure self-image did not prevent the ambitious Sumner from flirting with antislavery Democrats.

In support of equality, in 1849 he challenged segregation in Boston’s public schools. Attacking “discrimination on account of race or color,” he argued that the Massachusetts Constitution established “Equality before the Law.” Segregation was “in the nature of Caste.” It imposed a “stigma” felt by black children and separated them from the “healthful, animating influences” of study with their “white brethren.” Massachusetts’s common schools should further “the Christian character of this community.” Instead, segregation was “a monster” and constituted “Slavery, in one of its enormities.” Though Sumner lost his case, the direction of public sentiment in Massachusetts was on his side. Only six years later the legislature outlawed segregation in public schools.

The Compromise of 1850 roiled Massachusetts politics. Daniel Webster shocked many when he supported the Compromise measures, including its fugitive slave law, and then resigned his Senate seat to become secretary of state. As parties splintered, Charles Sumner promoted cooperation between Free-Soilers and other opponents of the Compromise. Consistently he denounced the soon-to-be-hated fugitive slave law. Its provisions seemed to encourage federal magistrates to return individuals to slavery without a trial or sufficient evidence. Sumner always called this law a “bill,” saying that it was unconstitutional. Soon a strange coalition of anti-Compromise politicians won the state elections, and after months of balloting, the legislature sent Sumner to the U.S. Senate over the aristocratic Whig candidate, Robert Winthrop.

There he began a career marked not by legislative success but by periodic, principled speeches. These were lengthy, formal, pedantic addresses—oral performances filled with literary and historical allusions and occasionally abusive language. For each speech Sumner dressed elegantly and spoke from memory for hours. Often visitors packed the Senate galleries to hear his orations. His reputation as a symbol of Massachusetts’s idealism and morality, plus the timely recurrence of national crises, kept him in the Senate for decades.

In August 1852 the new senator staked out his free-soil position in an address titled “Freedom National; Slavery Sectional.” Declaring that he was no politician, no party loyalist, but “a friend of Human Rights,” Sumner attacked the fugitive slave law and slavery’s influence. After citing “the injunctions of Christianity,” he reviewed history to show that slavery in the United States was “in every respect sectional, and in no respect national.” The Founders fought for human rights, condemned slavery, and viewed slaves as persons. Both the Declaration of Independence and the Northwest Ordinance proved that the federal government “was Anti-slavery in character.” At its founding slavery existed nowhere “on the national territory.” Though some original states held slaves, the federal government was “a Government of limited powers” with “no power to make a slave or support a system of Slavery.”

In an era when the federal government was far smaller than it is today, states’ rights was a principle accepted, in large measure, by all. It also was less than a principle—a tool that proved useful for supporters or opponents of slavery. To halt slavery’s growing influence, Sumner emphasized that “the States are the peculiar guardians of personal liberty.” Congress had no power to legislate for slavery’s “abolition in the States or its support anywhere.” States’ rights thus protected “Freedom in the Free States.” No law could take away “Trial by Jury in a question of Personal Liberty.” The fugitive slave law was a “usurpation by Congress of powers not granted by the Constitution, and an infraction of rights secured to the States.” Lacking “that essential support in the Public Conscience of the States,” it became a “dead letter.” Approvingly Sumner quoted the man who sat next to him: Senator Andrew Butler of South Carolina. Butler had declared that a law that has to be enforced at the point of a bayonet “was no law.” Sumner agreed and praised the older man as someone who, had he “been a citizen of New England, would have been a scholar.” At this early date Butler was one of a number of Southerners with whom Sumner was “on excellent terms.”

His antislavery stand won Sumner some important friends in the nation’s capital. Francis Preston Blair and other prominent Washingtonians invited him to dinner. But the new senator soon faced criticism in Massachusetts. None of the elements of the unwieldy coalition that had elected him trusted him fully. Abolitionists always wanted him to be more energetic and outspoken—they felt he wasn’t doing enough. Former Democrats distrusted him because he had been a Whig. Then, in 1854, debate on the Kansas-Nebraska bill altered Sumner’s fortunes. It revived his popularity in Massachusetts and severed his previously friendly relations with Southern legislators.

Sumner fought Douglas’s bill both in a formal address and in spontaneous debate. His “Landmark of Freedom” speech identified the Missouri Compromise as a sacred “compact” between the sections. The Founding Fathers had been antislavery. They had opposed its spread and expected the institution to die out. Their guiding principle was “its prohibition in all the national domain.” Following that principle, the Missouri Compromise had outlawed slavery in most of the Louisiana Purchase, north of 36 degrees 30 minutes. Northerners had not wanted slavery to spread at all, but in the Missouri Compromise they bowed to the South, which was the “conquering party.” Southern lawmakers were parties to the Compromise and shared in its “solemn obligations.” Now, thirty-four years later, the South had no right to rescind the agreement and open Kansas and Nebraska to human bondage. All depended on preserving the “compact,” for “nothing can be settled which is not right.” North Carolina’s senator George Badger called this speech a “masterpiece” of oratory, even though it was “on the wrong side.”

Sumner’s speech enraged Stephen Douglas and Southern senators. The Appeal of the Independent Democrats and the arrest in Boston of fugitive slave Anthony Burns inflamed emotions further. Southern senators called Sumner a “fanatic,” a “serpent,” and a “filthy reptile.” Sumner retaliated in kind. He said that his critics’ “plantation manners” were on display—they imagined they were not in the Senate chamber but on “a plantation well stocked with slaves, over which the lash of the overseer had full sway.” When Senator Butler challenged him to say whether he and Massachusetts would return a fugitive slave, Sumner replied, “Does the honorable Senator ask me if I would personally join in sending a fellow-man into bondage? ‘Is thy servant a dog, that he should do this thing?’”

Thereafter Southerners cut Sumner socially and tried to ignore him in debates. But his importance as an antislavery leader grew. Late in 1855 Sumner met with Salmon Chase, Nathanial Banks, soon to be Speaker of the House, and Francis Preston Blair. Together they considered steps to achieve “an organization of the Anti-Nebraska forces for the presidential election.” Sumner also talked with John C. Frémont, who was being mentioned as a possible nominee of the new party. When the Republicans had their first meeting in Pittsburgh in February 1856, Sumner enthusiastically endorsed its declaration of principles. Along with the Blairs and Lincoln, Sumner had done his part to build a Republican Party.

But to African Americans this party seemed to offer little. “Free soilism,” said Frederick Douglass, was “lame, halt, and blind” because it would not demand the “overthrow” of slavery. “Limiting it, circumscribing it” was inadequate. Black Americans wanted and deserved “practical recognition of our Equality.” “That,” said Douglass, “is what we are contending for.”

Unending conflict over Kansas and slavery would soon aid the new party. Its stature in national politics would increase, and its ability to influence events would grow. The members of the Republican Party stood united on one great question: they were against the extension of slavery. But race and the status of African Americans remained divisive questions for Republicans and for the nation.

Reprinted from "Lincoln's Dilemma: Blair, Sumner and the Republican Struggle Over Racism and Inequality in the Civil War Era" by Paul D. Escott, courtesy of the University of Virginia Press.

Shares