A few years ago, back around the halfway point of President Obama's first term, the vast majority of Americans held only one real opinion about the country of Afghanistan: the desire to get out of it as soon as humanly possible.

It had been more than a decade since President Bush invaded the country in response to the terrorist attacks of 9/11, and for Americans who still even remembered the war was technically ongoing, the years spent occupying Afghanistan looked like a tragic waste. From the president on down, everyone seemed to have the same goal: getting the U.S. military out of Afghanistan as soon as possible, with a civil debate to be held to determine when that time happened to be.

Everyone, that is, except Ted Rall, the popular cartoonist, graphic novelist, journalist and war correspondent who traveled to Afghanistan to report on the invasion in 2001, and who never thought that we should've occupied the country to begin with. Now, some 10 years later, Rall found himself once again pushing against the tide, hustling with some fellow cartoonist/journalists to get in to Afghanistan in order to get a firsthand look at what America had done and what it was preparing to leave behind.

And did we mention he did both of these trips more or less by himself, without being helped by, or embedding with, the U.S. military?

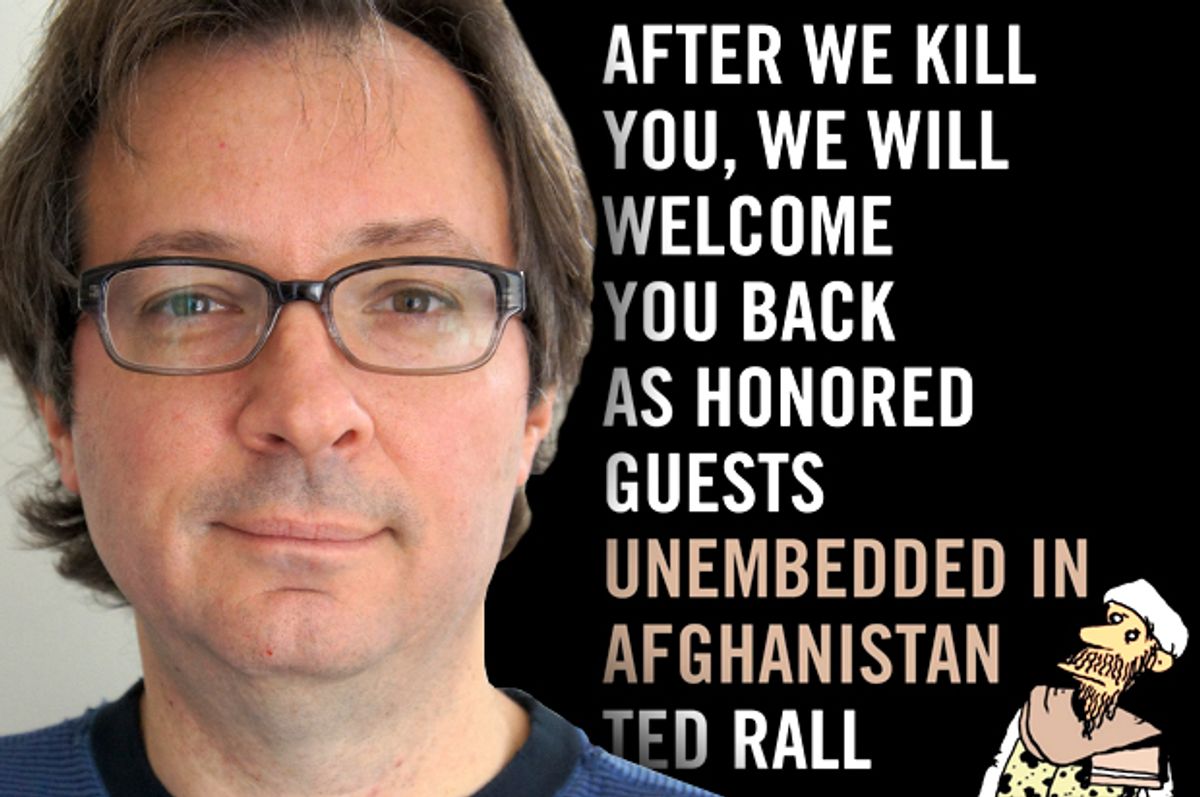

That story, along with lots of Rall's signature artwork and deep, extensive knowledge of Afghanistan's history and culture, makes up the heart of Rall's new book, "After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back as Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan." With America's eyes, after a painfully brief respite, once again firmly fixed on the Middle East, Salon recently called Rall to discuss his book, how the media still fails to cover Afghanistan, his thoughts on the late James Foley, and why he's worried that leaving Afghanistan now might be nearly as bad an idea as occupying it in the first place.

Our conversation is below, and has been edited for clarity and length.

You start the book with an extended retelling of recent Afghanistan history, most especially the events precipitating the invasion. Could you tell me why you did that, and how you interpret the years before and after 2001?

The reason I put this 30-page history of the invasion and what led up to it at the beginning of the book is twofold. First, I feel it’s important for anyone ... who is discussing history or politics to lay their cards on the table and say, “This is where I come from ideologically, and these are my assumptions. Then you can decide whether you want to follow me down this rabbit hole" ...

So the pre-history of the October 2001 invasion of Afghanistan is not a vacuum, even though it was in the [U.S.] mainstream media. There were a lot of rumblings that the U.S. might have gone to war [in Afghanistan] before 9/11, certainly; [and] correlation is not causation. The U.S. might not have gone to war in Afghanistan if not for 9/11. But it still might have.

The year 2001 saw failed negotiations for a pipeline project that had been languishing since the ’90s. Ever since the mid ’90s, there'd been a plan to run oil and natural gas from former Soviet Central Asia across Afghanistan, and that plan had been picked up and then abandoned, usually due to the security situation in Afghanistan over the years. In 1998, the plan was abandoned after al Qaeda bombed the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. But then, when Bush came into office in January 2001, the administration revived negotiations with the Taliban and the negotiations went quite a ways.

The negotiations ultimately broke down during the summer of 2001. The pivotal moment — the money quote that is often brought up in conjunction with [this version of] the story — is Wendy Chamberlain, who was then the U.S. ambassador to Pakistan, telling a Taliban representative that Afghanistan could either expect a carpet of gold if it signed the agreement, or a carpet of bombs [if it didn't]; and it’d be their choice. They weren’t able to come to terms, financially, and the Taliban walked away. Two months later, 9/11 happened, and the U.S. was at war.

The thing is, Central Asia and South Asia watchers were actually kind of surprised by the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, because there was so much more reason for the U.S. to respond to 9/11 by invading Pakistan than there was Afghanistan: Most of the training camps were in Pakistan, not in Afghanistan; most of al Qaeda was in Pakistan, not Afghanistan; Pakistan is a far more destabilizing influence in South Asia and Central Asia than Afghanistan ever was. At the time, I thought that Afghanistan was more of a dry run for Iraq, to test out new weapon systems, and because we had to hit something and Afghanistan was easy.

So this book is, among other things, a piece of media criticism, and a real inside view of what it's like to report on something as unfamiliar, complicated, distant and dangerous as the war in Afghanistan. The media changed a lot in the time between your first visit and your last — but do you think the quality of the mainstream media's coverage of Afghanistan changed? Or are the problems basically the same, just different in degree or consequence?

They're basically the same problems. There used to be a word, “Afghanistazation,” which referred to any story that was deemed too obscure to be worth covering, or too hard to cover intelligently, so why bother? And it’s all very reflective of the legitimate challenges news organizations face in covering Afghanistan: It is far. It’s hard to get to. It’s dangerous. It’s remote. And it’s difficult to understand.

Afghanistan is a less easily understood country than many others, and it seems that, for the bottom lines of many news organizations, it’s not worth it for them to maintain an expensive Kabul bureau, with all the security concerns and so on that they obviously would have to worry about. So what tends to happen is, reporters get "parachuted" in. They often don’t know anything about the country, and so they have to hit the ground running. Sometimes they come up with good results; more often, not.

The big change has been the embedding program. That didn’t exist in 2001. In fact, the Pentagon developed the embedding program due to the high casualty rate among Western journalists in Afghanistan during the fall of 2001, so the Pentagon rolled the program out for the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The embedding program has been very pernicious for a lot of reasons. But the biggest one is from the standpoint of readers and viewers who are just not getting the story, because the journalists who are embedded aren’t in a position to get any story other than the experience with troops.

It’s Stockholm syndrome. These are reporters who are literally traveling with these troops: eating with them, bonding with them and, in many cases, depending on them for their lives. So what you might get is a good story about troops but you’re not going to get any sense of what life is like among ordinary Afghans, or how the Afghan people perceive the U.S. presence or NATO or anything else.

It’s almost become standard or even mandatory for reporters to travel embedded. When I pitched this idea [of going to the country without a military embed] in 2010, my editors at the LA Times were very reluctant. They didn’t want me to travel independently. They were really concerned about my security. They thought that if something happened to me they would be liable — but I think genuinely they didn’t want anything to happen to me.

One of the most telling incidents was when [cartoonists] Matt [Bors] and Steven [Cloud] and I were pulled over and detained by the Afghan National Army in the northwestern part of the country, in a Taliban-controlled area, and we were accused of not being real journalists, even though we had press cards and we had ID, and our stories checked out. "You could not possibly be a journalist," an officer told me, "because journalists don’t talk to ordinary Afghans and we saw you talking to ordinary Afghans."

You can’t cover Afghanistan properly without talking to the troops or seeing things from their point of view. But you also can’t cover it properly only doing that — and that’s really been the [U.S. mainstream] coverage, certainly ever since 2002. That’s been it. That’s all we’ve gotten. There hasn’t been much coverage and there hasn’t been very good coverage and it’s still astonishing, how much of the country goes completely unreported on. You can still go to entire provinces that have never seen an American reporter, and we’ve been occupying that country for 13 years.

Tell me a little about the ordinary Afghans' perspective. Do they subscribe to a similar narrative of the U.S. invasion as we do? Namely, that it was a consequence of 9/11, and that the U.S. military is leaving because Americans are sick of the occupation?

I’ve never met a single Afghan who had any understanding of the relationship between 9/11 and the U.S. presence in Afghanistan. In fact, I’ve never met a single Afghan who even understood what happened on 9/11, understood the scale of it. I was repeatedly having to explain it to people, having to explain these buildings and how big they were and how many people were in them and how it affected the American psyche and so on.

Whenever you asked [Afghans], regardless of their age or their politics or their tribal affiliation, they’d all say the same thing: The only reason the U.S. was in Afghanistan was because the U.S. was the dominant superpower in the world; and from their point of view, whoever is the dominant superpower in the world at any given time invades Afghanistan. So we're just there because we could — they all think that.

If Americans think Afghans understand that whatever suffering they’re going through is somehow tied to 9/11, no; they should be disabused of that, because Afghans just don’t think that. That’s just universally true. They think we’re there because we hate Islam or because we want to steal Afghanistan’s natural resources or because it’s strategically important or "I don’t know, but they’re here, and I just have to deal with them!"

There's something vaguely Kafka about that. It's kind of existentially bleak and yet has a touch of black comedy to it as well.

Yeah. They always call us "the foreigners," which just refers to the inevitable foreign presence that’s always there, whether it’s Soviet advisers in the 1960s and ’70s or the Red Army in the ’80s or whatever it is. "There’s always foreigners here. We’re a weak country. We can’t defend our borders. The foreigners come and go; we shoot a lot of them, and then they leave." Black humor is absolutely a huge survival tool for people who live in stressful circumstances — and Afghans are very, very funny people.

One of the more interesting parts of the book is when you discuss how out of step you've been with the general public in the U.S. when it comes to Afghanistan. Back in '01, you were saying that invading the country was a terrible idea; but now you actually worry that our departure will lead to Afghans losing some of the gains that have come during the past 13 years. Are you worried that, after we leave, a civil war could erupt and destroy much of the basic infrastructure developed throughout the occupation period?

Yeah, I am worried. I think it’s important when you’re a journalist to report the uncomfortable truths that go against your own ideology. I don’t think we ever should have been in Afghanistan to begin with, but now that there have been so many improvements — there are fewer dropped calls in Kabul than there are in New York City, for examples — you really kind of hesitate to see that go.

The focus on infrastructure might seem soulless to anyone who hasn’t experienced the lack of it, but before 9/11, Afghanistan was a 14th-century country. The lack of roads, the lack of electricity, telephones and so on meant people had become really insular. You’d meet people and they wouldn’t say, “I’m an Afghan.” They’d say, “I’m a Takari” or “I’m from [wherever]," etc. It was just a medieval mentality. Every time I would pull out a map, people would just gather around, fascinated, because they had never seen a map of their own country!

[Infrastructure] really has a huge psychological impact. The idea that people in Harat can go to Kabul and back and forth... They know about each other now. They have more of a sense of nationhood, which had vanished during 26 years of war, and is now in danger. If all that stuff gets blown up again, aside from obviously all the human carnage, there’s also going to be a tremendous national trauma that is impossible to measure and that you'd just hate to see.

One thing I wanted to ask you about is what your thoughts were when you first saw the story about the late James Foley, a photojournalist who was kidnapped and murdered by ISIS. Did finding out about Foley's death make you think about your own reporting and the danger you've either experienced or escaped?

Yes. There’s no way I could watch that video and not think, there but for the grace of god... I’ve been around those kinds of people and in their hands. Anyone who’s reported from those kinds of conflicts has been. So it’s impossible not to think of yourself in that situation.

Do you think his situation has anything to do with the "Afghanistazation" you were talking about earlier, with news organizations not having the resources to send people into dangerous areas in a way that's at least somewhat safe? And the end result is people like Foley going it alone, with a greater risk of danger?

It’s an interesting question. I’ve been jealous of people who work for major news organizations and the support they can get. There are people who can dial up a satellite phone and have a military chopper extract them from wherever they happen to be, if they’re in trouble.

What’s interesting is that it cuts both ways, because when you travel independently, the way Foley did and the way I do, it also makes you safer in certain ways — especially in Muslim countries, where there’s a religious and cultural requirement to provide hospitality to an unarmed traveler. I’ve been in a position where guys will say, “I don’t see why we shouldn’t just kidnap you or rob you or kill you,” and I’ve used that [tradition].

I certainly feel that the military embedding program is the worst of both worlds, because you don’t get the story and you’re a target, because you’re traveling with occupation troops. I also feel it’s really, really irresponsible for journalists to participate in the embedding program, because it sends the message that journalists are biased and not interested in getting all sides of the story, that they’re only traveling with troops.

Shares