All the way back in 1998, Sarah Waters announced her roguish intentions toward the historical novel with her first book, "Tipping the Velvet," a romp about a cross-dressing lesbian stage performer, titled after the Victorian slang term for cunnilingus. After two more twisty, picaresque novels set during that era, she decamped to the 20th century, with "The Night Watch" and "The Little Stranger," brooding tales set in the straitened and unsettled Britain just after World War II; the latter is one of the best literary ghost stories of the past 50 years.

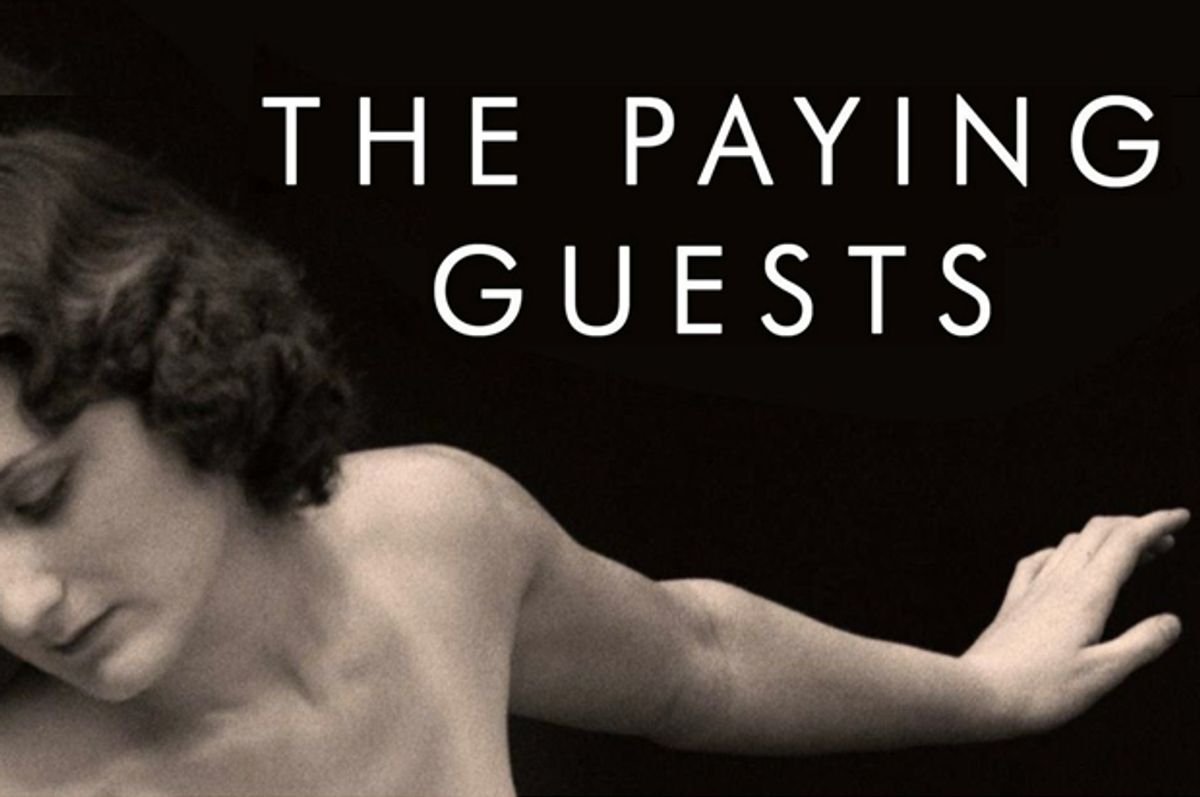

With her latest, "The Paying Guests," Waters turns to the 1920s and delivers what feels like three novels for the price of one. It begins as a meticulously observed comedy of awkward manners told from the point of view of Frances, a tightly wound, shabby-genteel woman in her late 20s who lives with her mother in a big house in a London suburb. The two women are obliged to take in lodgers -- Len and Lillian, a slightly vulgar young couple of the rising "clerk class" -- to make ends meet. Within a few weeks, Frances and Lillian have tumbled into a secret affair and "The Paying Guests" becomes the stuff of D.H. Lawrence, a story of torrid, forbidden trysts conducted behind a facade of conventional feminine respectability. Before things have a chance to cool down, the two lovers get caught up in a fatal act of violence and "The Paying Guests" enters its third stage, a tense tale of crime, mystery and suspense that culminates in a nail-biting courtroom drama.

No wonder the novel clocks in at nearly 600 pages, although it's not like you notice or mind. Exceedingly difficult to put down, "The Paying Guests" should scratch the same big-novel itch that Donna Tartt's "The Goldfinch" satisfied last year. Waters, who is Welsh and lives in London, is currently wending her way through the American branch of her book tour, and met with me recently in a Manhattan tea shop to talk about her work.

I believe "The Paying Guests" was inspired by a real historical crime?

It was. There was this murder case from 1922 in London, called the Ilford Murder. It involved Edith Thompson, who was this young unhappily married woman who was having an affair with a much younger man, Fredrick Bywaters. He was away at sea a lot, so Edith wrote him letters in which they talked very frankly about sex and the fact that she got rid of a baby. She also sort of flirted with the idea of murdering her husband, stupidly or criminally. She'd talk about poisons and claim to have fed her husband ground glass -- that kind of thing. Eventually, Freddy is home on leave, follows the husband and wife on the street and murders the husband, stabs him. The police arrest him, find Edith's letters to him in his stash of things and arrest her for incitement.

When they did the autopsy on the husband, they didn't find any trace of ground glass, so people often think that she was just fantasizing. Anyway, they were both found guilty and both hanged. She seemed to be such a woman of the time, a lower-middle-class woman at a time when the lower middle classes were doing quite well. They were on the upswing, and she was very sexually confident and ambitious. She was a businesswoman, really. And then the fact that it was in the suburbs, when there was anxiety as to what was going on out there.

What interested you about the crime and the period?

I didn't really know much about the '20s except for popular stereotypes about flappers and that. At first, I couldn't find anything to grab hold of for the period, and then I remembered the Ilford Murder and another case from around that time. I liked the idea of writing about a domestic crime, ordinary people caught up in something dramatic and tragic.

There's a brilliant series of books called the Notable British Trials series and they're basically transcripts of the trials. They're absolutely gripping to read, and they also give you access to ordinary people's voices. That gave me all sorts of insights into domestic arrangements and people's jobs and daily lives and stuff. It was a brilliant way into the period. Then there were the dynamics of the relationships -- the husband and wife and the male lover -- which got me thinking, “What would happen if the lover was a female?” That was when it came alive for me, because it changes so much. It was so obvious to the police that the woman had been having an affair. But in "The Paying Guests," they just can't see it because her lover is a woman.

Frances is frustrated that they can't be open about their love. They have to hide it, but it also seems like the secrecy has to be stoking the flames.

That's the other thing, of course. Now, if the Barbers had moved in and Frances was having an affair with Leonard, they wouldn't be able to stay at home together during the day, you know, they wouldn't be able to go to the park together without being instantly identified as sweethearts. Instead there's Lilian and Frances, meeting on the bandstand as if they're onstage, but to the people around them, they're not readable as lovers.

There definitely is this sense that the two of them would never have become involved in the first place if Lillian didn't happen to be living in Frances' house. It takes Frances a while to realize how attracted to her she is.

Their relationship is a product of a very particular social moment.

Let's talk a little bit about that social moment. This is a depiction of post-World War I London, and it feels a little bit like the post-World War II of "The Night Watch."

That was something that surprised me, the similarities.

Everyone's fretting about these scruffy ex-servicemen wandering the landscape. That's immediately who everyone blames when they learn there's been a violent attack.

The early part of the decade was still very much in the aftermath of the war. Lots of novels of that period feature the returned ex-serviceman and the returned veteran as figures who might on the one hand be benign and rather pitiful, but on the other might be disturbed and angry. And I think a lot of servicemen did feel, coming back from the war -- as with all wars — that people didn't want to know anymore. They liked them when they were over there doing their dirty work but when they were back without a job and without a home wanting something -- a reward or recognition ... It surprised me to learn of the bad feelings between all sorts of people after the war, between classes, between the sexes, between generations. The younger generation felt they had been sent off to war by the older generation. And politically there had been strikes. Even during the war there had been strikes. There was a lot of muttering in the working classes. I liked the idea of London being uneasy.

For Frances it's kind of a fallen world. She'd been politically involved before the war. And she was kind of a suffragette.

The war, it kind of took the wind out of the suffrage sails. In fact, parts of the suffrage movement said, “We're putting this on hold for now,” and really threw themselves into the patriotic tide of things. I think they had this amazing moment before the war around women's politics that was never quite recaptured until women's lib, really, in the '60s and '70s. So for a figure like Frances who had been involved in that, it is another example of a loss of possibility. I like characters -- there are lots of them in "The Night Watch" -- who had an interesting, lively past and now they're washed up and don't know what to do with themselves.

In your earliest books, the characters have this dashing quality, but in the more recent ones they're coming to terms with limitations. Which is weird, because people think of the Victorian Era as being all about limitations. Yet, in "The Night Watch" and "The Little Stranger," the characters seem far more hemmed in than in your Victorian novels.

"Tipping the Velvet" and "Fingersmith" in particular had that tremendous energy that I slightly miss. I think it's my age, and I think it's the ages I'm writing about and the age I'm writing in. It's been a heavy time for the West, a time not unlike the early 1920s when people are feeling that the world is newly dangerous. Frances, when she opens the newspaper, it seems to her like the world is just full of conflict and unhappiness.

It starts out rather quietly, yet the third part of the novel is this insanely tense crime-and-punishment story about the search for a murderer and Frances and Lillian trying to hide the true nature of their relationship.

I did enjoy that in a diabolical kind of way. For poor Edith Thompson, she didn't know she was in a crime story. She thought she was in a love story, until this dreadful mistake that plunged her and Freddy into a nightmare, an absolute nightmare. That was one thing I really hung onto. I really liked that idea. Sometimes lives do get compelled into melodrama, they do get propelled into nightmare

In one way, "The Paying Guests" does resemble your great Victorian pickpocket novel, "Fingersmith," because the main character has an understanding of her situation and then she learns something that completely capsizes that. She thinks she knows about what's going on, then she realizes she was catastrophically wrong. A big theme in "The Paying Guests" becomes Frances' growing doubt of Lillian.

It's true, and I suppose not unlike "The Little Stranger," I definitely wanted it to be open to interpretation. We never get inside Lillian's head, of course, and she's always a bit opaque to us. After reading it, my agent said, “I see this is a crime story and that's complicated by the love,” and I said, “Wait a minute, I want it to be a love story that's complicated by the crime.”

One of the fascinating things about your work is that you're not presenting these relationships between women in an idealized way. Is that important to you?

Yeah it is, especially with this book. In previous novels, the women have done terrible things to each other but in this novel I was interested in the fact that other people get harmed as a result of their love. That was very important later on both in terms of their relationship and in class terms. We meet them and there's this evident class dynamic between them, which they seem to get over. But then suddenly [after a surprising late development in the story] we realize there's this whole other class aspect going on as well. One of the best compliments you can pay your character is to give them a really hard time. It treats them like a proper human being.

There's a maturity in being able to write novels about lesbian relationships and not feeling obliged to depict them as this perfect bond that society is unjustly crushing.

I'm also conscious that being able to write about lesbians is a luxury of living in my own society, one that's fairly relaxed about gay lives. Plenty of other parts of the world wouldn't have that luxury. I remember when "The Night Watch" was published in Russia, they sent me a review and translated it for me and it said something like, “This novel gives us a fascinating glimpse of the tragic lives of these poor ...”

“These poor, poor, tragic lesbians!”

Of course! And of course it's going to seem like that because in "The Night Watch," in particular, the characters are so unhappy. But for me, it's about lesbian characters occupying proper human status and that means I can make them miserable if I want to.

In "The Night Watch" their discontent seems less about their relationships and more about the end of the war. They didn't realize that the ordeal of the war was in some ways the high point of their lives.

Which I think was true for lots of people. It's always true after wars, as dreadful as wars are. People have been living life at a certain pitch that they can miss.

Your first three books have a Victorian setting but they're also Victorian in the sense of having elaborate stories with a lot of characters and plots and lots going on. It sometimes seems like the Victorian era is a bit like a theme park for modern readers. It's so far away that we can't really relate to it. It just seems like a fairy tale land. So it's easier to set stories there that are ...

Larger than life.

Yes! That's what we think of as a Victorian-style narrative. So now you're telling stories in the 20th century. It feels like you have a new narrative style to go with that.

Yeah, definitely, I really noticed that shift when I moved to the '40s. I love Victorian fiction. I love the exuberance of it, and I really enjoyed taking that on, especially with "Fingersmith." That's the most obviously pastiche, I suppose, just having fun with a certain kind of Victorian theme. Then, moving on to "The Night Watch," I was much more interested in trying to find a narrative tone that somehow felt like it belonged to the period. Because it's still within living memory, I didn't want the characters to be larger than life. I wanted them to be life-size. That was a very interesting shift, and I've never really lost that since then.

I'm interested in how the past is always a bit of a stage set to us. Once it gets past a certain point, it becomes fixed, mythologized. The Second World War, especially in the U.K., is such a big part of our national narrative. We've got so many images of the Blitz and the Blitz spirit. I suppose I feel I'm taking on that slightly mythologized landscape and finding a way to make it feel alive but also enjoying the fact that it's been mythologized and putting gay characters -- or a poltergeist -- into it to unsettle it.

This novel also seems very of the 1920s in its focus on the very nuanced shiftings of Frances' internal life. It's like Woolf --

Or Katherine Mansfield.

Yes, this close observation of the way our emotions are in constant flux. Which is also unusual in crime narrative.

It did feel like it was such big feature of the literature of the time, that new prioritizing of subjective experience, so it felt like it had to be there in "The Paying Guests" as well.

There's also the incredibly closely observed physicality of this domestic situation. What it means when you take in lodgers. These strangers are there socially, which is weird enough, but you're also going into the lavatory and finding their pubic hair. These people are bringing new life into Frances' house, but at the same time it's an awkward and kind of gross thing. Even Lillian, her physicality seems to gross out Frances a bit at the very first. It's sort of ...

Intrusive.

Yes, and it's not genteel.

It's unrestrained, like when Frances talks about Lillian in a kimono and the flesh underneath being unrestrained, which is very sexy but a bit alarming.

Frances is middle-class and Lillian is lower-middle-class?

Yeah [laughs sheepishly].

So would Frances be a "lady" and Lillian not?

Oh yes, Frances would be a lady. I sometimes call her upper-middle-class, but strictly speaking you'd call her middle-class. And Lillian is definitely lower-middle-class. In her working-class mother's background, she'd pass for a cut above. But to a "real lady" like Frances it would be obvious that she's not a lady. It's terrible, really.

The palpability of this physical world feels right for describing the domestic situation in the first part of the book, but then when it comes to the crime -- I have to admit I got a bit nauseated at points because it was just so vivid. The reality of violence and what it does to a body.

I was interested in pursuing that. We see murder all the time on telly and films and sometimes it's dealt with in what feels like a sensitive way, but often it's glibly dealt with. I really wanted to think it through. What would it be like to carry a body downstairs? I've carried enough futon mattresses downstairs over the years to imagine how your arms would ache.

What's especially convincing is how crippling the characters' reactions to the violence are. We're used to these crime narratives where the people are so self-possessed and calculating in the aftermath of something like that.

They bounce back. That's mad, and it really annoys me. It would be so much more untidy than that. That was the thing, the untidiness. This is a novel about mess -- emotional mess, physical mess, moral mess. There's Frances doing all that housework in Part 1, and then the mess goes to a completely different level.

Did you start out thinking, "I'm going to write historical fiction. This is what I do," like, say, Philippa Gregory?

No, but actually Philippa Gregory was a great inspiration to me. Her Wideacre Trilogy. Have you read it? It's so great. I read them at exactly the time I was beginning my Ph.D. and I was reading lots of lesbian and gay genre fiction. Then I read the Wideacre Trilogy, which is incredibly feminist. I mean, they're madly commercial, just bonkbusters, really kinky, incest, everything. They're fantastic. The third one, especially, is very politically left-wing. I thought it was amazing that this commercial fiction could have this political agenda to it.

So in that sense, definitely with the first novel, I was full of ideas and excitement about historical fiction. And I still have that basic excitement in writing about the past and breathing new life into old stories. I'm still very excited by the strangeness of the past and trying to capture that for a reader. I really love that. And yet in some ways, it was a bit of an accident that I'm an historical novelist.

Do you have any rules about what you must or will not do? It's a huge imaginative project, trying to think like the residents of the past.

Everything changes when you go back, especially those things that interest me most, things to do with social history, rather than the grander narratives of history. People's domestic arrangements, the way they shared or didn't share space. The way people felt about their bodies and other people's bodies. All those small signifiers of dress and behavior and class. I love all that stuff. It's about inhabiting that world but also staying enough in this world to make it interesting for a reader. Something that seems to belong to its own time yet that can still speak to us in our world. I enjoy that balancing act.

I've never written about real people. I wouldn't say it's a rule. It's just that I feel a bit squeamish about writing about real people. But it's more about where my interests are, which is with people who haven't left a mark on the historical record. With women, on the whole, with gay stuff.

And yet with "The Little Stranger" you wrote from the point of view of a man.

It felt right for that novel. I wanted him to be a doctor because doctors are mobile. He needed a reason to come and go from the manor house. He could have been a woman doctor, but I would have had to deal with the issue of her gender in a way I didn't want to in that novel. He could be more invisible as a man.

On the other hand, the depiction of Len, the husband, in "The Paying Guests" is surprisingly sympathetic, given how jealous Frances is of him. Still, she often can't help feeling sorry for him.

He's stuck in an unhappy marriage, just like Lillian. I didn't want him to be a cad or a villain. This was a time in which men had been harmed on a massive scale. London was full of disabled men with emotional problems. Len has been through the war, got through it, and Frances never asks him anything about his war. In earlier drafts I had a moment when she realizes that. God, he's been through the war, Frances, and you're not interested? So he is a poignant figure to me.

The war was so gendered. Women had a hard time waiting at home for news and losing loved ones, but what young men went through in that war was a horror.

The toll a war takes on the men who fought it seems to be something societies are always underestimating. We're only just now beginning to admit that many of the veterans of World War II were traumatized because we're still invested in the idea of that as the Good War.

And you have to wonder how that damage manifested itself in family life across the generations. It must have, of course. In Len's case, he was also benefiting from this expansion of opportunities opening up for lower-middle-class men. His family a generation before would have been working-class. Then suddenly he's in a white-collar job, with a salary and leisure time. He's playing tennis.

He's upwardly mobile, whereas Frances and her family are on the way down. That was a big thing that happened after that war, a shakeup of the class system.

Definitely, and a lot of unease among middle-class people about that rising class.

The "clerk class" as the characters in "The Paying Guests" call it.

Yes -- that's great, isn't it? A great phrase. It was Edwardian if not earlier in origin, but definitely there was this big expansion. Ready-to-wear clothes were more accessible, so there was this tremendous anxiety among the middle class, who were often wondering, "Are you really middle-class or do you just look middle-class?" I think the way you dealt with that was to become more of a snob.

For your next book, will you stay in the 20th century? Is a return to the Victorian era a possibility?

I've not wanted to go pre-20th-century since I made this move to writing about less larger-than-life characters, I quite like it. I've never wanted to go back into pantomime history. And I've never wanted to go pre-Victorian ever because the language becomes a bit weird and people start saying "gadzooks" and things like that. That's never really appealed.

But I don't honestly know about the next book. In an ideal world, I'd like to write another '20s one. But maybe I've finished with the '20s for now. The '30s are interesting. But I have the merest glimmer of ideas for the next book, and I'm not pursuing it right now.

Shares