"Seventy-five. That’s how long I want to live: 75 years."

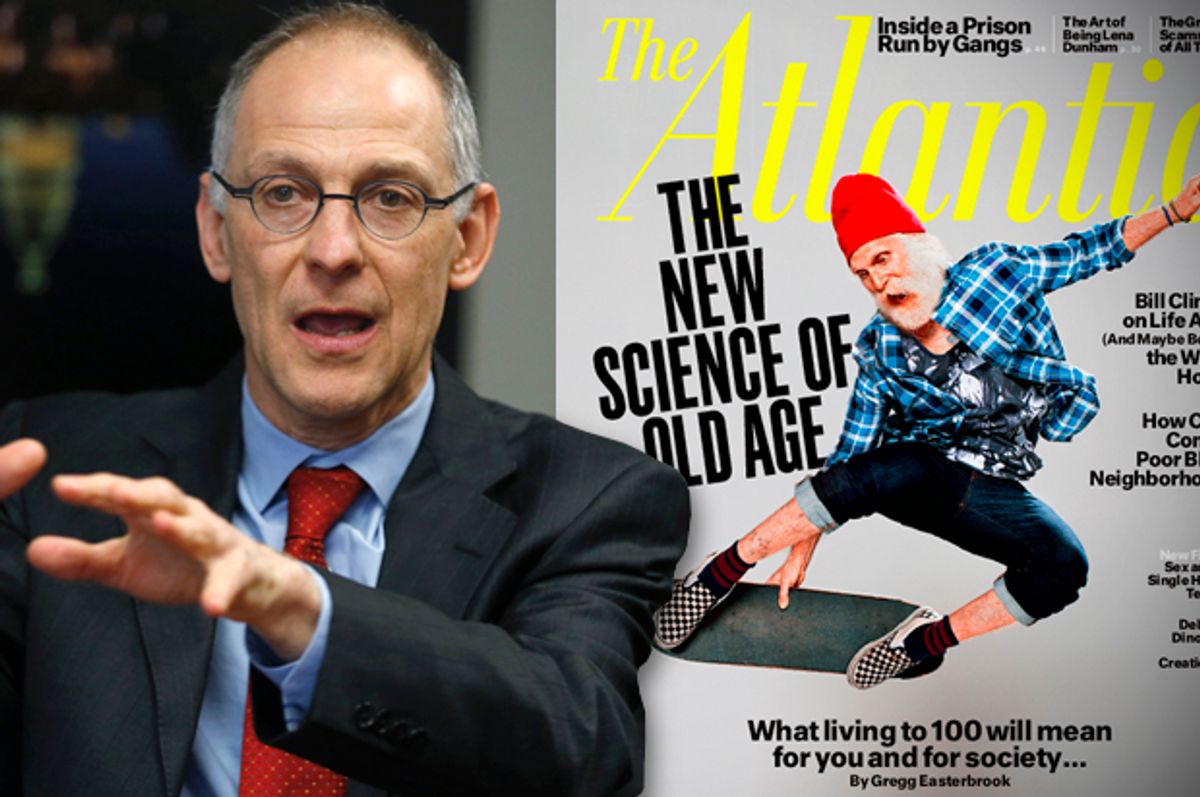

– Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel

Dr. Emanuel, now 57 years old, is smart, mature, productive and provocative in his ideas about avoiding aging. He is the age of my son, who was a colleague of his at the National Institutes of Health. At 86, I look at them both as “young” and still growing up. Unfortunately, Emanuel’s recent essay in The Atlantic -- titled "Why I hope to die at 75" -- has contributed tremendously to the negative views of aging that plague our society today. I am as passionate about changing these attitudes as Dr. Emanuel is about dying less than two decades from now. So is my 51-year-old colleague and co-author, psychologist Mindy Greenstein. Why?

Dr. Emanuel’s image of life after 75 is bleak indeed: a time of deprivation and loss of creativity, a time when we are sluggish and no longer able to contribute to the world around us. He especially fears being remembered as “feeble, ineffectual, even pathetic.”

I am an elder who has treated older patients with cancer for over 35 years at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, helping them cope with the challenges of being ill. Dr. Greenstein is a clinical psychologist and consultant to my geriatric psychiatry group. Clinical experience and much social science research refute many of Dr. Emanuel’s assumptions about life after 75. Large population studies by economists and psychologists asked adults of all ages, and from different countries, to rate their sense of well-being on a scale of 1 to 10. When they looked at the data by age, they found it had a fascinating shape: a “U.”

Self-reported well-being starts relatively high for people in their early twenties, after which time it starts to steadily decrease, particularly for the “sandwich generation." Well-being plummets to its lowest level for people in their early fifties. After this trough, well-being starts to increase again, and keeps increasing over the years, until, by age 85, it’s even higher than it is for those in their twenties.

If Dr. Emanuel looked more closely at older age, instead of fearing it, he might find that along with the negatives are many positives. The functional limitations he cites — decreased ability to walk a quarter of a mile, or climb 10 stairs, or stand without special equipment — are only part of the picture. It can be hard for overachievers to see these positives, especially if they confuse professional esteem with quality of life. And so, he is proud of a father who is “the prototype of a hyperactive Emanuel,” but also weary when his father slows down in his 80s, even if he says he’s happy. While Emanuel seems to acknowledge the huge importance of mentorship, a role that the elderly can and do play, he devalues it nonetheless as a “constriction of our ambitions and expectations.”

Further, what Dr. Emanuel dismisses as mere “avocational interest” -- what he describes as "bird watching, bicycle riding, pottery, and the like" -- may in fact provide the liberating experience of no longer worrying about careers or what people think of us. Wisdom does not depend on being the fastest person in the room. It is related to the ability to take multiple perspectives, to be flexible, to compromise and to navigate social conflict, all of which were found in research to be highest in the 60 to 90 age group. Nelson Mandela was already in his seventies when he helped unify post-apartheid South Africa, and he was past 75 when he hosted the famous rugby game that helped cement the newly integrated nation.

But personal growth in older age is not only for the extraordinary people of the world. One of the members of our support group says she came out of her shell at age 70.

The late psychoanalyst Hedda Bolgar (who died at age 103) once said that she didn’t understand “why people are so afraid of being old. It seems to me that what people see only is the loss or the deterioration or the minus, and they don’t see that there are tremendous gains, the ease and the security of the feeling of essentially being able to cope.” Asked at age 97 what her favorite time of life was, she responded simply: “Now.”

One thing many of us do agree with Dr. Emanuel about is the importance of not trading quality of life for quantity. He is quite right to question the assumptions of “the American immortal’s… manic desperation to endlessly extend life.” The notion that additional years is always better can lead to destructive expectations. (Some late 19th-century reformers, for example, suggested that living “right” would result in a healthy lifespan of hundreds of years, and elders’ “bad character” was to blame for any frailty.) Medical care at any age can be a trade-off between longer life and better life, and it is sensible to think about when we should be willing to make that trade and when we should not. That is why empathic end-of-life counseling can sometimes vastly improve our quality of life, and why we should do more to help incorporate it into medical care. But many factors should go into these decisions, age being only one of them.

In fact, many in our support groups are very comfortable with their own mortality, and quite enjoy the experience of living in the now that results from it. The relative closeness of death allows us -- more easily than when we were younger -- to appreciate “smelling the roses” and enjoying the simple pleasures of each day. We enjoy the present enough to joke about disabilities and death. There are many ways to enjoy a good quality of life, whether or not we slow down compared to our younger selves.

And there are other ways to contribute to the world besides being a “hyperactive Emanuel,” even if Dr. Emanuel turns out to be correct that age-related medical problems will slow him down. Slowing down has its benefits, too. It allows us to see the bigger picture better, or to compromise, because we don’t need to win every argument quite as much as before. It allows us to appreciate the meaning of our actions, and learn more about who we are and what we want, and, especially, what we want to teach others. It gives us the time to appreciate beauty, and cultivate a sense of gratitude for just being alive.

Maybe our ambitions don’t constrict with age, as Dr. Emanuel fears. Maybe they evolve into new — and more selfless — ambitions like mentoring, that are at least as important as producing papers or rounding with your residents, and just as much of a contribution. The social scientist Lars Tornstam refers to these collected experiences as gerotranscendence, the ability to feel more like a part of the larger whole. Anyone who has gone through crisis at any age can attest that this ability can make a great difference in how well we cope.

In older age, we contribute not only the wisdom collected over many years, we also contribute by serving as models of survival. Or, as my granddaughter says, “survivors of life.” And as role models for how to cope when things don’t work, including various body parts.

In older age, we are also, in Dr. George Vaillant’s words, “keepers of meaning.” Our relationships with our children, grandchildren, and younger colleagues become more precious as we try to pass on our values to them, sharing perspectives forged over many years. Even over centuries.

We hope, along with Dr. Emanuel’s children, that he does not get his wish, that he lives -- and lives well -- well past the age of 75. He will become wiser as he grows older. And we need that kind of wisdom, as Cicero once noted, to counter some of the hot-blooded decisions of the young. There are many ways to enjoy life, and many ways to contribute to it, at all ages. This 86-year-old would bet money that when Dr. Emanuel reaches the age of 74, he willl raise his limit to at least 76.

Jimmie Holland and Mindy Greenstein are the authors of "Lighter As We Go: Virtues, Character Strengths, and Aging.”

Shares