I'm always late picking up on the latest Ed Champion news because I cut myself off from the source many years ago. If you're like 99.99 percent of the population, you've never even heard of the guy and may reach the end of this story feeling like you haven't missed much. I tend to agree. But the literary community on Twitter, a small but active group, has been unable to talk about anything else over the past four days, and that means I'm obliged to write about it myself.

Champion was part of the early community of literary bloggers who emerged in the mid-2000s. Many of the more talented members of that contingent -- Maud Newton, Lizzie Skurnick and Champion's longtime partner (now ex) Sarah Weinman -- have gone on to careers in publishing and journalism. But not Champion, who has complained repeatedly of his inability to find an agent and sell a novel. The barb of that fact seems to have lodged deep inside him and festered.

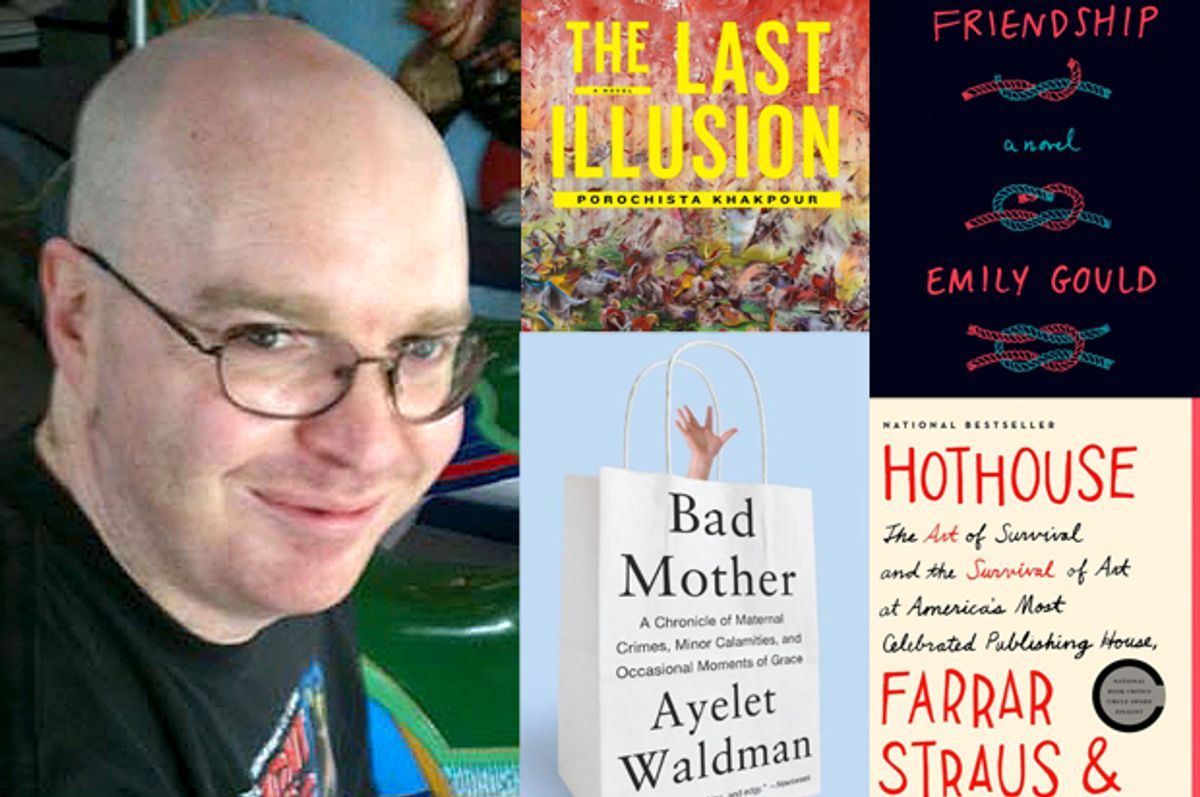

Late last week, Champion -- whose contrived "feuds" and vendettas against various literary figures number in the dozens if not the hundreds -- threatened to reveal an embarrassing personal detail about a novelist, Porochista Khakpour, with whom he had until very recently been friendly. Champion demanded that Khakpour publicly apologize to him, alleging that she "smears me with lies." Khakpour maintains that Champion was set off when she deleted an insulting comment he made about another writer on her Facebook page. Champion's diatribe against Khakpour culminated in the fulfillment of his blackmail threat, and shortly thereafter his account was terminated by Twitter.

It was déjà vu all over again. Only three months earlier, in June 2014, Champion had generated widespread outrage across various social-media networks with an 11,000-word blog post about several young women writers in Brooklyn and how much he hated them and their work. The language he used is venomously over-the-top and, like every Champion screed I've ever read, contorted with labored metaphors of bodily disgust and humiliation. It's misogynistic because its targets are women, but Champion has also written with equally bombastic loathing about male writers and their bodies, picturing one author's "cock hardening" as he researched a book and describing him as a "diseased mongrel."

I have most of these quotes from secondhand sources, however, because almost a decade ago I stopped reading anything Champion wrote. Not that I had extensive knowledge of his work, but when a Google Alert directed me to a page that Champion had created to present an ongoing discussion of what a terrible book reviewer I am, I clicked around his blog a bit and got a general impression. "Troll," I told myself: "And you don't need to be reading anymore of that, young lady." I'd been writing on the Internet for 10 years, so I knew the drill pretty well.

From that point onward, I scrupulously avoided Champion's blog and a podcast he did under a pseudonym, even when alerted to the fact that I'd been discussed on either one. I ignored his friend requests on Facebook and when Twitter came along, I blocked him. You will have to excuse me if my grasp of the Champion timeline here is a bit vague because I also refuse to do much in the way of catching up on Champion's "work." Nobody needs that stuff in their heads.

On the whole, I found it pretty easy to live in a Champion-free world. He was probably insulting me -- I certainly couldn't stop him from doing so -- but since I didn't know about it, I didn't care. Every so often I'd overhear novelists swapping horror stories about being interviewed for his podcast and how the conversation would swerve into bizarrely combative digressions. "Don't do that show," they'd fervently warn each other. Other friends became the objects of his countless obsessive grudges. They'd announce that they'd acquired a nemesis, this demented guy named Ed! I'd sigh and welcome them to the ever-expanding club. Publicly, I never even acknowledged Champion's existence. Because that's the world I want to live in.

I was fortunate to realize that Champion was a troll before I had had any interaction with him. Apart from two fleeting encounters at parties, I've never communicated with him in any fashion. I believe that strict non-engagement is the most effective way to cope with anyone whose primary goal is to get the biggest possible rise out of others. But not everyone else Champion targeted had the chance to see his dark side before they became entangled. In particular, young writers like Khakpour recount being befriended by Champion and Weinman soon after they arrived in New York, a not especially welcoming city. At some point a difference of opinion would arise -- Salon contributor Michele Filgate objected to Champion's attacks on another writer -- and the one-time pal would be deemed a betrayer by Champion and subjected to a barrage of verbal abuse.

When Champion got really riled up, he'd pull stunts like telephoning the employer, agent, editor or thesis advisor of those who had offended him, demanding that they be punished or fired. Novelist Ayelet Waldman once dared to joke that Champion's preoccupation with insulting her must be motivated by lust for her husband, Michael Chabon. Champion repeatedly phoned her agent and publisher with threats of a libel suit until Chabon persuaded his wife that life would be easier if she sucked it up and apologized. She did.

There are countless stories like these. They have been pattering into my inbox like raindrops since I put out the word that I was looking for instances in which Champion physically threatened his targets. It didn't happen very often, but in every case I've been able to track down, the victim was a man. Many would prefer not to have their names dragged into another Champion mess, but former Salon film critic Matt Zoller Seitz has written that Champion "threatened to put out a cigar in my mouth after I confronted him over his silly preening." New York magazine writer Boris Kachka received a voice mail in which Champion threatened to punch him in the face for commenting on his blog. Later, Champion would characterize this message as "performance art." The writer and blogger Ron Hogan has tweeted that Champion "threatened to assault me at a book party."

Other targets were hounded more than menaced. The critic and editor John Freeman, who went to high school with Champion, was the subject of several strange autobiographical blog posts. Champion began to email Freeman as well, and for a period Champion turned up whenever Freeman spoke at a literary event, "taking my photograph and blogging about my appearance and other stuff like that." There were a few months when every public appearance by then-New York Times Book Review editor Sam Tanenhaus seemed to include a moment when Champion rose from the crowd and tried to present Tanenhaus with plate of brownies. I'm not sure anyone ever figured that one out.

If Champion has any remarkable literary gift, it seems to be the ability to convey a physical threat without explicitly stating it. "If you think I'm done with you, Mr. Freeman," he wrote in one email, "to paraphrase another man working in another evolutionary medium, you ain't seen NOTHING yet." As yet, no reports of physical violence on Champion's part have surfaced, although Khakpour says she filed a police report regarding his blackmail attempt. It's unclear exactly how much of his behavior might be illegal, but it seems likely most of it is not. While I can attest that Champion's grotesque and highly personal criticisms certainly feel assaultive, they don't actually constitute assault. Writing nasty things about public figures on the Internet is not against the law.

Champion's June 2014 diatribe against several women writers in Brooklyn registered as misogynistic, but it's typical of his vitriolic attacks on both genders. At times, Champion has styled himself as a rabble-rousing feminist, barraging staffers of the humorous publication the Onion with demands that they publicly denounce their employer for posting a sexist tweet about the actress Quvenzhané Wallis. Like many Internet habitués, Champion apparently found righteous indignation -- and the opportunity to parlay it into attention and recognition -- to be a heady drug.

Champion's attack on the Brooklyn writers, however, landed at a moment when sensitivity to literary sexism was, as it remains, particularly acute. The blog post exploded across the literary world's social media accounts, generating much outrage and prompting other writers, critics and journalists to share similar experiences of being attacked by Champion. Just how had this obviously disturbed and volatile person been allowed to rage unchecked?

Some would-be Champion critics said they were physically afraid of him. Others, like me, figured complaining about him would fuel his image of himself as a crusading gadfly and seed further attacks. Still others point to his relationship with Weinman, a publishing industry reporter who is described as both widely liked and widely feared. Personally, I've found Weinman to be consistently generous and collegial despite Champion's long-standing grudge against me. But others report occasions when Weinman backed up Champion's outlandish animosities or attempted to persuade them not to make a fuss about his misbehavior.

Weinman works for a media outlet called Publishers Marketplace, an online trade publication largely devoted to tracking book deals, sales figures and other industry data, with some news aggregation. There's no evidence that Weinman retaliated on behalf of Champion there, and it's more likely that her enormous Twitter following (200,000) is what made some Champion victims too scared to speak out. Weinman did support some of Champion's vendettas there, but she separated from him after his attempted blackmail of Khakpour. (Weinman was contacted for this story but declined to comment. She also reported that Champion was "in no position to comment.")

Yet Champion’s power was largely illusory, a mirage he'd concocted of smoke, mirrors, boasting and bullying that worked best on vulnerable newcomers. He did not work for a large publication or command any influence outside of a small circle of acquaintances. A few early freelance assignments came to nothing once editors learned that to work with him was to invite lunatic tantrums and meltdowns. In the office of the New York Times Book Review during Tanenhaus' tenure, he was referred to with exasperation as Special Ed. He had his blog and his podcast, but so do countless other insignificant cranks. Being denounced by Champion became almost a rite of passage, in which one observed the sacred rituals of the “block” and “unfriend” buttons. His rampages were anything but a secret — the swapping of Ed Champion war stories enlivened many a late-night literary get-together, and I warned more than one younger writer to steer clear of him however friendly he might initially appear.

Then, in June, aided by the accelerator of Twitter, disgust with Champion's behavior finally boiled over. It became appallingly clear how many people -- of both genders -- he'd attacked, baited, harassed, insulted and badgered over the years. So thunderous was the condemnation within the small world of literary social media that Champion began to claim that he'd received threats and that his life was ruined. One tweet read, "No money, no job, no gigs, no agent (a MS out with three). Not good enough. So I’m going to throw myself off a bridge now. No joke. Goodbye." This was followed by tweet of a photograph taken at the edge of a bridge with the caption "Low guardrail. Great view."

However serious Champion may have been about this particular threat, he did not carry it out. Soon he was vowing to stay off Twitter "for months" and to get professional help. Did he? Who knows? Three months later he was not only at it again, but he'd escalated from posting borderline psychotic screeds masquerading as literary criticism to threatening to publish the name of a man who he claimed had nude photos of Khakpour.

While some observers have deplored an alleged climate of "silence" surrounding Champion's misdeeds, it bears pointing out that the resounding drubbing he received for his tirade against the Brooklyn writers did not truly chasten him. To the contrary. Champion's next outburst was not only more misogynistic than his previous one, but it seems to have been patterned after the recent celebrity photo-hacking scandal, which was widely decried for its misogyny.

It sure looks like Champion was deliberately trying to provoke the same response on an even larger scale. For a few days this summer, the guy who couldn't get a freelance assignment or an agent was suddenly the talk of the literary world. Was it tempting, once the drama had died down, to seize that attention again? Even if the sexism in Champion's post on the Brooklyn writers was, as he claims, unintentional, he knew very well that the type of threat he leveled against Khakpour was frankly sexist. Pundits across the nation had been saying so for weeks.

"He didn't care if he destroyed himself as long as he hurt you," one publishing insider recently remarked to me of Champion. It's difficult to plumb the workings of a mind as troubled as this blogger's, but it's less difficult to figure out why a community allowed itself to be abused by him. If part of it is down to Weinman's protection, more of it is due to desperation. Champion had an audience, however modest, for his blog and podcast, as well as around 8,000 Twitter followers. Publishers sent him review copies of new titles and booked their authors for interviews with him. Some of those authors did not know that Champion was considered "crazy" and that he had harassed other writers, but many did. If some of his targets viewed him as too small-time to hurt them, many authors and publishers still felt that no outlet was too tiny or fringy to help.

When I published a book in 2008, my publicist informed me that Champion had requested an interview. "No way," I said, "am I talking to that guy." She expressed relief. The entire company, she explained, loathed Champion because, as the publishers of the late David Foster Wallace, they were sickened when Champion obtained and published information about the author's suicide before his family was able to announce it themselves. "But I don't feel that it's fair to keep a publicity opportunity from an author because I don't like the person offering it," she added. She was not alone.

It has become notoriously hard to win press attention for new books. When not pursuing some irrational vendetta, Champion has been willing to devote coverage to debut authors and some commercial novelists, like Jennifer Weiner, who have not been treated seriously elsewhere. (He also helped break the occasional important literary story, such as the plagiarism scandals involving Q.R. Markham and Jonah Lehrer.) Champion isn't the only blogger to do such things, but because he has been at it from the very beginning of the blogging boom, he has a larger audience than some. Part of the (manifestly imaginary) grievance Champion claims against Khakpour is that he "busted my ass and went out of my way to put THE LAST ILLUSION [her novel] in the hands of many."

But is whatever paltry help Champion has to offer worth the tolerance implied by accepting it? The first-time novelist he promotes today could well be the "traitor" he berates next month. "The thing to do w/ Ed Champion," Waldman tweeted on Friday, "is to cut off all oxygen. Stop sending him books, stop letting him interview, stop publishing him." This has been happening incrementally and it remains the most effective response to the vast bulk of his outbursts. Unless he violates the law or terms of service, no one can actually make Champion stop blogging -- or tweeting, should he set up a new account. Most of what he has written, however gross, angry and creepy, does not break such rules. And he obviously can't be shamed into cleaning up his act, as condemnation only seems to egg him on.

Say, on the other hand, Champion were to stop receiving review copies. Say authors and publicists were to refuse to talk to and deal with him. Say readers stopped bestowing on him the favor of their attention, which is still attention, the thing he seems to crave most, be it ever so angry and accusing. That would be a new and powerful form of silence. Champion could go on ranting and raving, as is his right, but when nobody, but nobody is listening to you, you might as well not be talking at all.

Shares