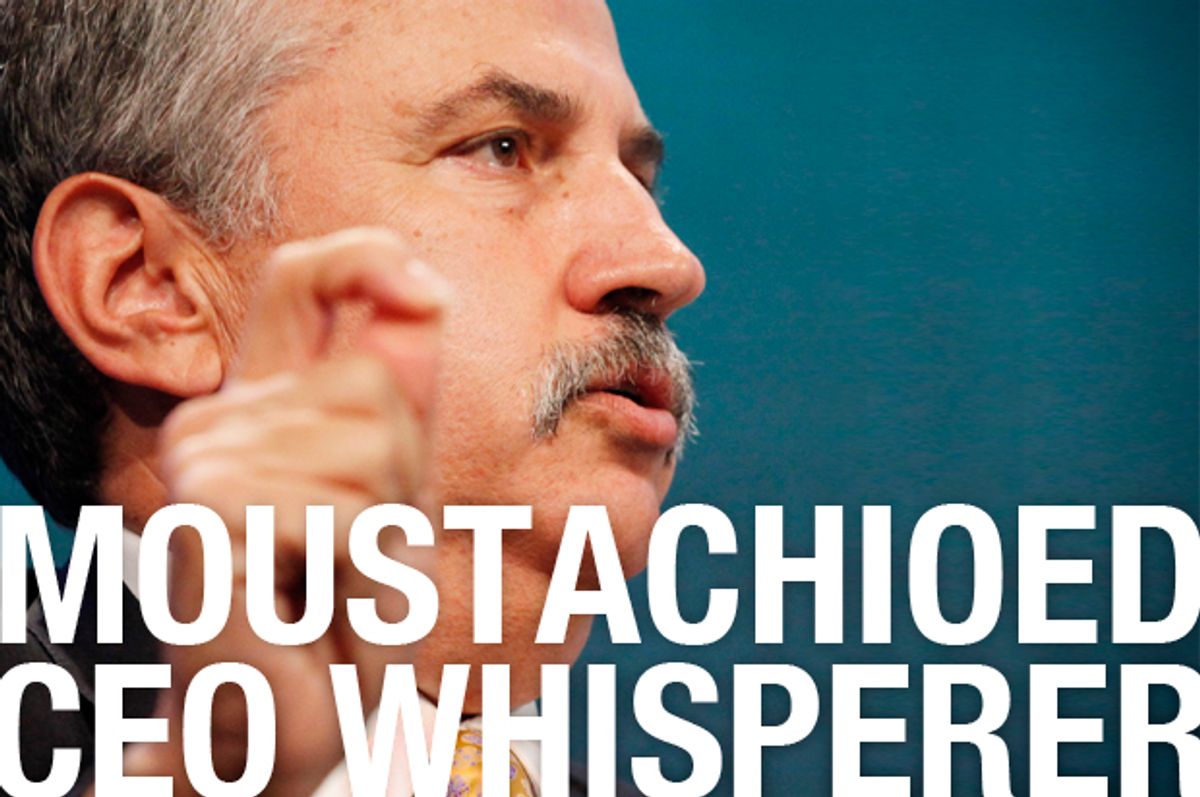

Cruising around the web lately, you may have noticed a certain rhetorical tic cropping up with increasing frequency and flair. Perhaps you’ve seen Donald Trump referred to as “tinted meatball Donald Trump.” Or Larry Ellison as “former Oracle CEO and descendant of Poseidon the Greek god of the sea Larry Ellison.” Or Tom Friedman casually characterized as “mustachioed CEO-whisperer Thomas Friedman.” Or “globalism’s rain man. Or “NYT mouthbreather.” You could call it the rise of the “celebrithet” (alternately, the “diss-criptor”): the whimsically vicious honorific, the moniker-as-putdown, now a staple of internet style.

If Internet-speak usually provokes in you a nasty Pavlovian response, akin to being shocked by a small electric cattle prod, you are not alone. In an interminable stream of “must-reads” and “whoa if trues,” it’s reasonable to wonder: How many article headlines can begin with “In Defense Of?” How many sentences can conclude with “because of course it did”? Online prose is often deadening, trite, and bland. But not the celebrithet.

Lindsey Lohan has been called a “trickster god left over from an ancient time to sow chaos among the living.” Taylor Swift is an “antique doll brought to life by black magic.” Zooey Deschanel has been variously dubbed a “sentient glitter cloud,” a “possessed Anthropologie mannequin,” a “hipster labradoodle,” and “overemphatic stage wink.” (Gawker even catalogued the many sobriquets it bestowed on her in a conveniently itemized list.)

But if Gawker popularized the celebrithet, Spy magazine was surely its progenitor. Spy produced such immortal gems as “short-fingered vulgarian Donald Trump” (Trump-bashing never goes out of style) and “bosomy dirty book writer Shirley Lord.”And over the years, the tic--so perfectly, intrinsically internet-ready--has spread to the far corners of the web. Richard Lawson, once one of Gawker’s most skilled practitioners of the trade, took it with him to Vanity Fair, where he has cranked out coinages like “celebrity lard saleswoman Paula Deen” and “child star turned human black hole Lindsay Lohan.” The AV Club’s Sean O’Neal is a pro as well: he has described Gene Simmons as “a 64-year-old man who makes his living as a rock ‘n’ roll clown” and Rob Schneider as “Adam Sandler’s comedy bar-to-clear.” Vulture recently had “human litmus test Lena Dunham.” The tic has infiltrated the TV world, too: a few weeks ago, “SNL” dubbed Trump (him again!) a “clown made of mummified foreskin and cotton candy,” perhaps one of the finest burns yet.

Why do these pithy labels deliver so much bang for their buck? First off, as any joke-writer can tell you, brevity is indeed the soul of wit. Just as the Twitter quip is the comic currency of our times, there’s something satisfying about reducing famous people, so over-covered by the media at large, to their absurd essence in the space of a few words. The humans who earn such labels -- D-list celebrities, bloviating columnists, lawbreaking pop stars and the like -- must reach a certain level of cartoonishness to be moniker-worthy.

The celebrithet in part reflects our collective exhaustion with the endlessly ridiculous online news cycle; it’s a kind of wink at the whole insane project of writing about the same bold-faced names again and again and again. The best sobriquets tend to emerge after a famous person has made headlines for so long that devoting more words to them seems unfathomable. Swift's ubiquity has prompted ever-more elaborate descriptions, such as “the slightly-dotty-but-kind grandmother who inhabits the lithe, nubile body of 24-year-old Taylor Swift” and “singer and definitely not a cat that body-switched with her human master Taylor Swift.” And witness the evolution of Justin Bieber celebrithets over the course of his many legal and personal imbroglios: he went from pop megastar and recovering racist Justin Bieber to Canadian petty crimelord Justin Bieber to human pissbucket Justin Bieber to bored miscreant Justin Bieber, all in the course of a few Bieber-saturated months.

In an online world that so often feels mean-spirited, so full of the notorious “snark,” the celebrithet is, crucially, playful. There’s a refreshingly communal feel to the piling-on, as writers take aim at their favorite targets, trying to one-up each other, or sometimes themselves. Just look at Caity Weaver’s baroque Lohan take from earlier this year: “American’s neighbor that they have to play with even though she always smells like cigarette smoke and one time she set a bug on fire so they don’t have to let her in their room but they do have to play with her out back for a few minutes because the moms are talking…” It's a rare example of a pleasant upside of web-writing--the way the whole online world can sometimes feel like one of those collaborative storytelling games when everyone adds a line, building on each other's ideas ad absurdum.

Finally, the moniker takedown has an undeniable old-school charm, like a throwback to a more refined insult era. Maybe a bit of a stretch, but still: there are echoes of the Algonquin Round Table in O’Neal’s dismissal of Dinesh D’Souza as a “poorly spelled placard who became sentient.” As a certain kind-hearted forest spirit might put it, haters gonna hate (hate hate hate hate). And celebrithets make doing so a lot more fun.

Shares