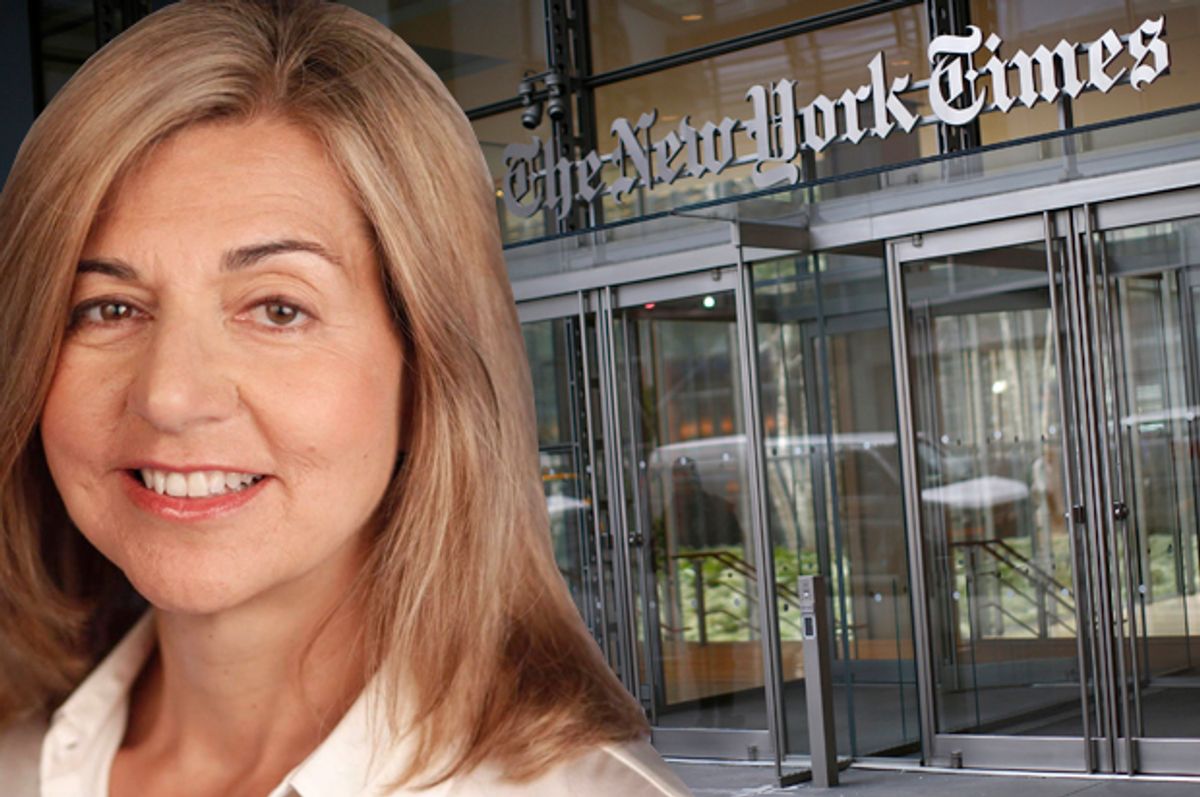

When Alessandra Stanley published her now-infamous essay on Shonda Rhimes in the New York Times last month, the backlash was swift and furious. Mostly, readers were aghast that the paper of record had failed to nix the phrase “angry black woman.” Stanley defended herself, saying, “the whole point of the piece—once you read past the first 140 characters—is to praise Shonda Rhimes for pushing back so successfully on a tiresome but insidious stereotype.” And through it all, there was one consistent voice of reason: New York Times public editor Margaret Sullivan.

“Intended to be in praise of Rhimes,” Sullivan wrote, “[the article] delivered that message in a condescending way that was—at best—astonishingly tone-deaf and out of touch.” Sullivan, thanks to that sentence, became a Twitter hero. Emily Nussbaum called the column “thoughtful and balanced”; novelist Gabriel Roth tweeted: “I don’t envy whoever has the public editor gig after @sulliview.” At every turn in the controversy, readers and critics seemed to be waiting for her to weigh in.

Today, the job of the ombudsman—the poor soul hired by a news outlet to engage with readers and scrutinize the journalistic standards of said news outlet—has been rendered somewhat obsolete. Reader engagement tools such as Twitter, Facebook, and the trusty comments section are now baked into the way newspapers publish and promote articles. What’s more, press critics like Jack Shafer and Felix Salmon and Erik Wemple, along with the thirsty young rubberneckers at New York, Gawker, and other media fishbowl websites, already spend a great deal of time kneeing powerful journalistic institutions in the groin. As current Washington Post editor Marty Baron has said, “There is ample criticism of our performance from outside sources, entirely independent of the newsroom, and we don’t pay their salaries.”

In 2013, Shafer wrote a piece for Reuters titled “Does Anyone Care About Newspaper Ombudsmen?” (Sixteen Facebook “likes”; eight reader comments. So, there’s one answer.) The piece was pegged to the news that the Post would be replacing its ombudsman with a dull-edged “reader representative." “I’ve witnessed greater reader noise,” Shafer said of the development, “after the cancellation of a comic strip.”

Shafer’s central point was that ombudsmen tend to suck. “Instead of roasting the paper for its transgressions,” he wrote, they “could be relied on to sympathize with the hard job of newspapering and gently explain the newsroom’s mistakes to readers.” That’s true. It’s also true that ombudsmen, as a class, seem fascinated by incredibly boring topics. Among the greatest hits penned by Patrick Pexton, the Post’s very last ombudsman: “Post Home Subscribers Get Price Increase Too” and “How George McGovern Inspired Me.”

But Margaret Sullivan's approach could hardly be more different. With two years of her four-year term as the Times’s Public Editor (Graylady-ese for ombudsman) under her belt, she has not only adapted to the speed of the web, but managed to keep pace with its topicality and bottomless appetite for controversy. Sometimes that's required stirring up controversy herself. But this is what makes her so different from her predecessors: she has ushered the position into a new media age by reimagining the very purpose of the job.

***

The history of ombudsmanship at the New York Times has not exactly been illustrious. Daniel Okrent--the paper’s first public editor, appointed in 2003 in response to the Jayson Blair scandal--was smart but antagonistic, and his acerbic style may have motivated the Times to hire a set of rather desultory successors. Byron Calame (2005-2007) inspired entire takedowns. Clark Hoyt, who held the job from 2007 to 2010, bemoaned upon his departure that he’d “felt less like a keeper of the flame and more like an internal affairs cop.” Arthur Brisbane (2010-2012), was widely perceived as a nitpicky, humorless pencil-pusher.

But Sullivan, who served as editor-in-chief of her hometown Buffalo News for 13 years before taking the Times job, is--to begin with--a far more regular presence on the Times’s website than those who held the job before her. As of this week, she had written 327 items in her two years at the Times. Over the same period of time, Brisbane had written a little more than half that much. Mostly, that’s because she conceives of herself not as a Sunday columnist—her print piece appears twice a month—but a writer who writes whenever something needs to be written. (Reached for comment, Sullivan said, "It's my practice, generally, to let my columns and posts speak for themselves.") In June, Sullivan wrote that columnist Nick Kristof “owe[d] it to his readers” to explain why he had championed an apparently fraudulent Cambodian activist. In her next item, she noted that Kristof had since written about the matter in greater depth, highlighted a few other new developments, then, still unsatisfied, criticized Kristof again. She has a knack for actually driving the "conversation," as they say, rather than just reacting to it.

Perhaps the clearest difference between Sullivan and her immediate predecessors is her blunt style: she is refreshingly frank about what she likes and doesn’t like about the Times. (She doesn’t pull her punches when holding her employer’s feet to the fire, to use two idioms that appear frequently in the realm of meta-ombudspunditry.) In 2013, Sullivan criticized a satirical Sunday Review piece related to the Boston Marathon bombing by “Curb Your Enthusiasm”’s Larry David. “The Larry David piece doesn’t [work],” she wrote, “not only because it was insensitive, but also because it was unfunny.” Earlier, then-Times Magazine interviewer Andrew Goldman got into a Twitter war with author Jennifer Weiner after asking actress Tippi Hedren in a Q&A whether she had ever considered sleeping with directors for professional gain; Sullivan wrote, “Given the level of obscenity and hideous misjudgment in Mr. Goldman’s Twitter messages, a clear social media policy at The Times may be in order."

For all this, Sullivan has generated a good deal of praise from fellow media observers. “She’s not annoyingly bad and that’s so refreshing,” Salmon told New York magazine at the start of her tenure. “I don’t care if she’s right or wrong; I just like that she’s engaging.” In the same piece, Wemple said, “The people on social media who really follow this stuff can commune with her because she recognizes and is trying to satisfy the medium’s need for immediacy.” Shafer, when we spoke by phone, was similarly appreciative. “I look forward to her columns in a way I didn’t to Brisbane’s or Calame’s or Hoyt’s,” he said. “She’s in the fray. She’s not ducking a fight.”

Take the statement she made two days after her first column about the Rhimes article, in a follow-up piece. First she issued a few legitimate, if uncontroversial, calls for greater staff diversity and rigorous editing. Then she made a subtler, perhaps more significant point: that the internet is in some way designed to gin up and amplify scandals just like this one:

In an era in which readers come to stories on social media or through recommendations from people they know, each story has to stand on its own; it’s disaggregated—it stands or falls alone, not as part of the whole. And it may come with the lens of opinion already in place.

This paragraph was not written to exonerate Stanley. But it did advocate that people read the story itself rather than base their reactions on a Twitter feed full of outraged headlines. Sullivan isn’t simply refereeing the journalism at the New York Times; she’s refereeing the way the internet responds to it.

***

Some requisite ombudsman history: The word “ombudsman” is of Scandinavian origin, shortened from justitieombudsman, which in the 19th century is what Swedes began calling the guy hired to deal with citizen complaints about the government. It is not in Sweden, however, but in another bureaucracy-happy nation, that the journalistic version came into existence.

Jeffrey Dvorkin, a former NPR ombudsman who recently completed a stint as the executive director of the Organization of News Ombudsmen explained to me that the first news ombudsman was appointed to the Tokyo daily Yomiuri Shimbun. Back then the big Tokyo newspapers all had ombudsmen; in fact, each desk often had its own. “The editors would walk in,” Dvorkin said, “they’d be sitting on opposite sides of the same table, bow at one another, and then have at it.”

The idea eventually migrated to Kentucky in 1967, where the Louisville Courier-Journal and the Louisville Times became the first American newspapers to employ ombudsmen. From there, the concept spread, and in 1970, the Washington Post rendered the practice de rigueur for much of the industry.

By 2003, when the Times hired Okrent, the ombudsmen bubble was ballooning. At what Dvorkin calls “the high water mark” for newspaper ombudsmen in the U.S., in the early 2000s, there were 45. Now, he estimates there are around 20.

The reason for the decline, along with the democratization of reader engagement online, is bound up in the general economic precariousness of the newspaper business. “A lot of large newspapers have dropped them, mostly for financial reasons,” says PBS ombudsman Michael Getler. “We’re an easy cut: You save money and you get rid of a pain in the neck.” Among major national news outlets, only ESPN, PBS, NPR, and the New York Times employ ombudsmen.

The Times’ relationship to its public editors has historically been a complicated one. “Like many of my colleagues, I’ve been deeply ambivalent about the job of public editor,” former Times executive editor Bill Keller (who has himself been criticized by Sullivan before) wrote me in an email. “It is a very, very hard job to do well, and even harder in the fast-and-furious, polarizing onslaught of social media. There is less time for reporting and reflection, less patience with nuance. It’s hard to separate people who are reacting to something the paper has published from people who are reacting to retweets of tweets about something they haven’t actually read.”

And while Keller praised Hoyt’s “open mind” and “fearless reporting,” he wasn’t sold that Sullivan’s webbiness has translated into good journalism. “She is prolific, and I think she tries to be fair,” he said. “I also think she sometimes gets caught up in the social media frenzy. Representing the readers’ interests is not the same as representing the loudest faction of readers.”

Sullivan does have a habit of singling out individual writers who happen to be under intense fire in the blogosphere, regardless of whether their ostensible transgressions represent a broader problem at the Times. The most notable example of this came earlier this year, when Michael Kinsley wrote a critical review—which itself was whacked around on the web for a while—of a book by Edward Snowden collaborator Glenn Greenwald. “There’s a lot about this piece that is unworthy of the Book Review’s high standards,” she wrote. “The sneering tone about Mr. Greenwald, for example; he is called a “go-between instead of a journalist and is described as a “self-righteous sourpuss.”

Whether or not Kinsley’s critique was fair, it was unusual for a public editor to ding a freelance polemicist for issuing his opinion. A current ombudsman who wished to remain anonymous (Guess who—there are only 20 of them!) said, “I don’t think it’s legitimate to go after the reviewer’s opinion. We generally stay away from editorials and op-eds.”

But more often, Sullivan critiques individual journalists in order to make a broader point about, say, social media etiquette, as when she got on Nate Silver’s case for a Twitter bet he proposed with MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough. And generally, rather than allow herself to be swayed by the army of amateur ombudspeople yelling about things on the internet, she douses them with a welcome bucket of ice water.

When readers were calling for the head of Times reporter John Eligon for, among other things, describing slain 18-year-old Michael Brown using the words “no angel,” Sullivan agreed that the word choice was “a blunder.” But she also found Eligon’s “reporting to be solid and thorough,” and gained from it “a deeper sense of who Michael Brown was, and an even greater sense of sorrow at the circumstances of his death.” On reader dissatisfaction with politically incorrect word choices, she’s been similarly willing to stake out unpopular ground. With respect to widespread dissatisfaction over theTimes’s use of the term “illegal immigrant,” she wrote: “It is clear and accurate; it gets its job done in two words that are easily understood. The same cannot be said of the most frequently suggested alternatives.”

Perhaps her finest—if not her most serious—moment came when addressing reader criticism of an especially ridiculous Styles Section trend piece on the supposed return of the monocle. The savage mockery that greets Times’ trend pieces, even ones about monocles, is getting a little old. Sullivan, recognizing this, managed to roll her eyes at the piece without endorsing cheap snark. “While the Times’s declaration of trends can sometimes seem self-serious, overblown and out-of-touch,” she wrote, “they also can — at their best — provoke moments of recognition and lively conversation. And because they occasionally provide a full day’s worth of hilarity, let’s pray that they never go away.” Added Sullivan: “By the way, I’m just back from biking to Bushwick. And I’m wondering: Has anyone noticed how many women are using lorgnette-handled opera glasses lately?”

Cold-water pouring was perhaps never more necessary than after ESPN suspended megascribe Bill Simmons several weeks ago, for calling NFL commissioner Roger Goddell a “liar” on his podcast. #FreeSimmons was born and a week’s worth of think pieces about ESPN’s cowardice were published. ESPN’s distinguished ombudsman Bob Lipsyte, one of the most courageous sportswriters of the past half century, was among the few to defend ESPN, agreeing with the network that Simmons had violated its journalistic standards.

It should come as no surprise, then, that when I asked Lipsyte, a former Timesman, for his opinion on Sullivan, he said: “I can only imagine how strong she is. The Times has never been friendly to oversight, even from within, it is alternately proud and resentful of the target on its back, and its audience arrives with an attitude, often an informed one.” Sullivan, he added, “ventures outside the wire every day.”

Simon van Zuylen-Wood is a staff writer at Philadelphia Magazine and a contributing writer at National Journal. He is on Twitter at @svzwood.

This post has been corrected to clarify Sullivan's quote about Andrew Goldman. Then-NYTM editor Hugo Lindgren wrote, "I thought Andrew was needlessly rude and insulting, and I told him that"; Sullivan described the "obscenity and hideous misjudgment in Mr. Goldman’s Twitter messages."

Shares