The runaway popularity of the HBO series "Game of Thrones" and the books on which the show is based, George R.R. Martin's "A Song of Ice and Fire," may be the best thing that's happened to the Wars of the Roses in ages. The complex dynastic conflicts that ravaged England for over 30 years during the 15th century have long been the bane of British schoolchildren. There are also plenty of adults who find the competing claims on the English thrones and the genealogies behind them fiendishly difficult to keep straight.

As every serious "Game of Thrones" fan knows, the Wars of the Roses -- traditionally seen as a struggle between the York and Lancaster clans -- was the primary inspiration for Martin's five (and counting) novels set in the imaginary kingdom of Westeros. The period also serves as the background for Philippa Gregory's bestselling novel series, "The Cousins' War," which is the basis for "The White Queen," a popular BBC series. And why not? Although a genealogical nightmare and hell to live through, the Wars of the Roses offer a saga of ambition, betrayal, madness, skullduggery, lust and violence that is a historical novelist's dream.

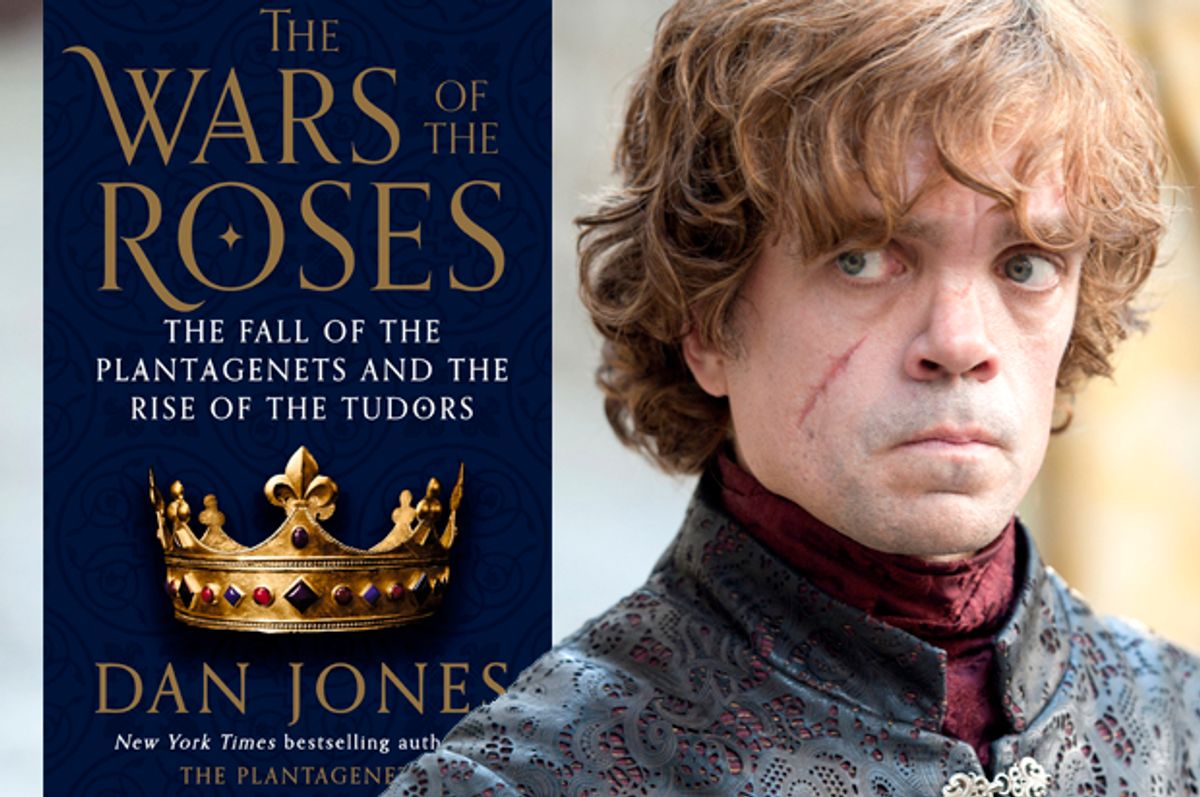

Now, journalist and historian Dan Jones -- following in the footsteps of such celebrated writers as Alison Weir -- has published what may be the most lucid and readable popular history of the conflicts yet. "The Wars of the Roses: The Fall of the Plantagenets and the Rise of the Tudors" is, as one early review put it, "both scholarly and a page-turner," told with the rigor of a historian and the instincts of a dramatist. (Jones' previous book, "The Plantagenets," a bestseller, has itself just been made into a series by Britain's Channel 5.) I recently contacted Jones at his home in London to learn more about the period that has inspired so many writers and filmmakers.

As a historian, how do you feel about the burst of interest that historical fiction and "Game of Thrones" has garnered for your subject?

I think it's great. I view historical fiction as a gateway drug for history. People are more comfortable approaching historical topics through fiction, and if 10 percent of the readers who love historical fiction or books like George R.R. Martins' get to reading history, that's great because that's a huge number of people reading history. I'm all in favor of bringing "the medieval world" alive, whether it's through "The White Queen," the Shakespeare plays, or "Game of Thrones" -- that kind of alternative medieval thing.

We don't think of Shakespeare as writing historical fiction, but his historical plays really are that, aren't they?

Those two cycles, the two tetralogies [comprising "Richard II"; "Henry IV, Part 1"; "Henry IV, Part 2"; "Henry V"; "Henry VI, Part 1"; "Henry VI, Part 2"; "Henry VI, Part 3"; and "Richard III"] are probably the most influential lens through which we view the 15th century. So much of what Shakespeare did with those plays -- although I don't think a lot of it was deliberate – reflects the common 16th-century views of what happened in the previous century. And that has remained the way people understand the Wars of the Roses. It's the most important historical fiction of all when we're talking about the 15th century.

The first I ever heard of the Wars of the Roses as an American child was in the Chronicles of Narnia. Someone is explaining something complicated to Lucy Pevensie, and she throws up her hands and says "It's worse than the War of the Roses!" So for a long time the only thing I knew about it was that it was impossible to understand.

I think more than any other book that I've written, this required a lot of careful planning. And a lot of thought about how a reader with no knowledge of the period – the kind of reader I have in mind when I'm writing – would be able to navigate their way through this incredibly complex story. This is not meant to sound flip, but a lot of the people in this story are called the same thing. There's a group of titles and sometimes there are figures with the same name and the same title but they're different people.

It's very helpful that you convey a sense of who each of these people are as distinct characters and what motivates them. The events don't just sort of happen, they're described as being caused by real desires and fears and animosities.

What I'm trying to do as a historian is to animate history and to allow people to understand it through the people -- underpinned by rigorous academic research, no doubt about that. The scholarly apparatus you see in the book is definitely all there.

If there's any one driving cause behind this series of wars, it's the catastrophe of having a weak king. Sometimes it's a child monarch or a madman, but the worst seems to be a frankly incompetent monarch like Henry VI.

To slip in a "Game of Thrones" reference, it's easier to deal with -- not a Joffrey Bartheon, but definitely a Tommen [Joffrey's younger brother and heir to the Iron Throne of Westeros]. That's easy. With a child, there are precedents for how to deal with it. Henry VI became the King of England at nine months. A child is obviously incompetent to govern. You can set up a polity that understands that the king is a child.

The much, much, bigger problem arises when the adult king is effectively childlike and can't or won't govern. That's what you get with Henry VI. And it's a problem that hadn't really been thrown up in the whole Plantagenet era. If you look at the earlier kings who made a complete disaster of it – and there are several: King John, Edward II, Richard II – normally, they go the other way. They're tyrants who misuse their power. That's a straightforward thing to deal with.

But what do you do when the king is just sort of not using his power, when he is so vacuous and inane and inert?

He was also catatonic for a while there.

But again, total insanity is slightly easier to deal with than when he wakes up. Charles VI of France was seriously insane. He had these bouts of mania that would take him over and last months at a time, when he thinks he's made of glass or that hot needles are being jammed into his flesh, or he runs around naked through the palaces in Paris smeared with his own shit and won't feed himself and tries to attack people with swords. Don't forget that Charles was Henry VI's grandfather. And when Henry's obviously catatonic, he's easy to deal with. It's when he's functioning again and appears to be operative and yet is not, that you're in this really difficult situation. You can't really depose him because he hasn't done anything wrong.

What you get with Henry VI is this slow rot in the government. It goes on for 30 years. What's impressive about that slow rot up until about 1450, is the way that the English polity holds together. We tend to think of the Wars of the Roses, the Shakespearean version of it, as a story of overmighty nobles, a load of barons, all ambitious to be king, who tear each other apart the minute there is a weakness in the crown. But that's not actually the case for the first 30 years of Henry VI's reign. Yet there is this slow rot, and eventually the whole thing collapses. Henry is in and out of sanity, and when he wakes up and appears to be competent again, factions start to pull him in one direction or the other. That's when it really seriously destabilizes government.

One big difference I noticed between England during this period and Westeros in "Game of Thrones," is that the English did have some semi-democratic or representative political institutions. There's Parliament. There's mayor of London, who is elected. Westeros is an autocracy.

That's the beautiful thing about "Game of Thrones," its cherry picking of historical periods. The great joy of watching it is spotting those things: "Oh, that's like the War of the Roses, but then hang on it's a little bit different." It works so well compared to something like "The Tudors," which is a dramatization of a well-known story. The suspension of disbelief is not as hard. You don't spend your time sitting there doing that horrible, nerdy historian thing of saying, "She wasn't tall, and she had blonde hair not brown hair."

Maybe the biggest difference between the culture of the Wars of the Roses and the one in "Game of Thrones" is the role of religion. It was such an important aspect of life in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance in Europe, whereas it's a lot more marginal in "Game of Thrones."

I had this same conversation with [writers and showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss] about 18 months ago, when I interviewed them. They said, "Yeah, but just wait, just wait." It becomes more and more a part of the story, the rise of this religious or spiritual element. But, you're absolutely right, that "Game of Thrones" depicts a sort of irreligious, unspiritual world to begin with, at least in Westeros. That's an important difference between that imaginary world and the real world of medieval England.

One thing that's always hard to do when you chuck yourself into the history, is to remember how important that religious mindset was. It was a world where religious zealotry and religious matters in general bear so much more heavily on politics, on culture, on society and on life than they do today. It can be very hard to step into that mindset.

The people in the story that you're telling seem to be torn between a ruthless warlord attitude and a reverence for Christianity with a quasi-religious reverence for the king. When Richard of York comes back to England from overseas, he's fed up with the attacks on him by his enemies, and he's finally decided that he's going to try to depose Henry VI. Everybody does agree that Henry is a terrible king and he's ruining the country. But the idea of deposing a king is just so, so taboo to them. They're completely shocked that Richard is advocating it. At the same time, these people have no compunction about grabbing an enemy and just chopping off his head!

That's another important point. There is this very primal, primitive level of violence in operation within an extremely sophisticated philosophical and religious worldview. And with rules that seem absurd to us today. This is a terrible king: why don't you just get rid of him? That makes perfect sense to us, but we also think "Don't chop his head off!" Because that seems barbaric to us. You have to flip your worldview if you're going to step into the Middle Ages. Chopping heads off? Okay, that's fine.

All in a day's work!

Exactly. But to oppose a king? Oh my God, the whole world would fall apart! That would disrupt the divinely ordained hierarchy of society.

How did they see the divinely ordained status of the king? It seems like the key difference. We're still surrounded by religious people today, but no one believes that leaders are divinely ordained anymore.

I suppose if you could boil it down into one instant, it's the moment of anointing. That still happens today. The next time there's a King of England, he'll be anointed in the coronation ceremony. It's not the coronation, it's the anointing, being touched by the holy oil. That leaves an indelible mark on the man. You have then stepped into kingship. You are in a form of communion with God then, in a divinely ordained position that can never be undone by mortal hands. That's the essence of anointing, the essence of becoming a king.

That's what is at the heart of Shakespeare's "Richard II," and at the heart of the real story of Richard II as well: the terrible deed that was done by deposing and killing an anointed King. You've messed with someone who has literally been touched by God.

It's like when people object to doing stem cell research today. You're messing with nature, with the rules of the world. Think about it in those terms.

Another interesting commonality between the Wars of the Roses and "Game of Thrones" is the way that aristocratic women, who have very little access to overt or official power, still find ways to exercise influence.

That is a very important part of what George R.R. Martin does, bringing in a lot of strong female characters. For me, with "The Plantagenets," the book that preceded this, it was very male. Apart from Eleanor of Aquitaine, there weren't a lot of really good female characters in the history. I felt like there was something missing from that book. Luckily, when you get to the Wars of the Roses, you have in particular Margaret of Anjou [Henry VI's queen] and Margaret Beaufort, who exercise power, often in many of the same ways as the men do, but with one important limiting factor: They can't lead troops into battle.

Now, if Margaret of Anjou could have led troops into battle, God knows she would have. She was really the directing force behind and the glue that bound her family, certainly when her husband went mad and also thereafter. She was quite able to marshal large groups of men and have them do her bidding. The trouble is, when you get to a big battle, say, the decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses, Townton in 1461, Margaret has to hang back. She cannot influence events on the front line. Because it's the 15th century, and that is the upper limit of what women can do.

Why that was direct participation in battle so essential in a leader? That's another idea that has really fallen by the wayside since.

It's a very warlike society, that's the first thing to remember. The test of masculinity really is the ability to fight and to be adept in battle. And kingship is the ultimate masculine position. What are the duties of a king? There are three. One is to dispense justice. One is to have a sort of priestly function, the defense of the church. But the third, and I would argue probably the most important, is to be a successful warrior. Even today: look at Prince Harry. What does he want to do? He's a soldier and he wants to be out in Afghanistan fighting. He's incredibly pissed off that they won't let them.

This is also one reason the Wars of the Roses eventually petered out. Everyone had to be out there on the front line, which leads to an enormously high mortality rate of male aristocrats in the English 15th century. You get to the end of the 1400s and there is virtually no one with any royal blood left. They've slaughtered each other.

Another element that turns up in this book and your previous one is popular uprisings. But it's not something you see much of in "Game of Thrones," at least not by comparison.

My first book was about the Peasants Revolt of 1381, which is the first time you see the ordinary English person, man and woman, front and center on the political stage. Stamping their feet, waving their bows and arrows and rusty swords. And saying, "Everything here is completely fucked up and we're going to reorder society." It's brilliant. It's such an antidote after you've gone through all these sophisticated, incestuous aristocratic contretemps, to have a big mob march on London to try to burn it down and kill everybody. I love the simplicity of the methods.

Those aristocrats were really full of themselves.

It's great, isn't it, when rebel commoners like Jack Cade and his lot come along in 1450 and start putting some heads on some spikes? That's when shit really gets real. Cade's Rebellion is a very important part of the Wars of the Roses and I try to emphasize that in the book. Those guys really did have a grasp of national politics. As a historian, you can't invent these things, so it's lovely when they come along. Finally, some ordinary people turn up and it's like chucking a grenade into the story.

Did those uprisings ever serve as a corrective to the aristocracy? Did it ever make them think that they should take the peasants into consideration more often?

I would not say that medieval rebellions generally tended to enlighten the governing classes afterwards. You look at the Peasants Revolt, well, the long-term follow up is the withering away of serfdom -- of actual bonded slavery, for want of a better term. But whether that withers away because the landowning class had a good long look in the mirror and decided they needed to stop being so beastly to the poor people below them, or whether it withered away because it was withering away anyway after the Black Death... Whether it's coincidence or causality is a moot point. I think in the immediate aftermath of peasant rebellions, people were a little bit careful not to antagonize the lower orders, and then they forget all about that and start in on a good bit of oppressing once again.

You have to wonder how much of a difference it would've made to any of the subjects whether they had a Yorkist or a Lancastrian king.

You mean: different king, same old shit? Yeah probably. A more important effect of the Wars of the Roses on ordinary people's lives, which you also see in the aftereffects of the civil war in "Game of Thrones," is what sprung out of the collapse of kingship and the general destabilization of authority. The inability of the king to keep the peace among his lords, and as a result the inability of the lords to keep the peace among their retainers and followers, led to a definite upsurge in criminality and violence.

One thing that's very striking about your book is that, although the historical record on this has to be pretty thin, you always make an effort to imagine how things must've looked or seemed to the children who are caught up in these power struggles.

It's the puppetry with which the kids are used. It was vital to have an heir or a child of any sort, and yet those children were in general manipulated by the adults around them. They have to grow up trying to get wise to manipulation really quickly, while it's happening to them.

You look at someone like Edward V, a very good example, the eldest of the princes in the tower. Suddenly, one day they come up to him and say, "Right Edward, you're king. Your dad's dead." He's presented with this choice. One uncle, on his mother's side, has been his tutor and has been looking after him and teaching him how to be a king. Then suddenly he finds himself sort of kidnapped by his other uncle, his father's brother, Richard of Gloucester who would become Richard III. And he's torn between the two of them, trying to make up his mind on the hoof. He's 12 years old. And of course, poor Edward V ends up disappearing in the tower, presumably dead at the hands of his uncle Richard.

That's what George R.R. Martin, and certainly the TV series, really captures: how young people are forced to grow up. In the series, we have Tommen now, the new King, and the poor lad is so clearly not cut out for it, so wide-eyed and confused about the whole thing. That always makes me think about Henry VI. He was obviously much younger, king at nine months old. But you have to grow up being the king and that must be weird enough as it is. Now imagine doing that while having never seen another king do it. You have no role model, no counterexample. You just have a lot of people telling you what it was like in the old days and how you have to live up to that.

Shares