One of the first things that becomes clear while reading Jonathan Eig's "The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution," is how we are still having many of the same debates about birth control that were happening in 1950. In addition to a series of existential moments of déjà vu, however, Eig provides a fascinating and fraught history of the revolutionary contraceptive. At the center of the story are four distinct personalities: a reproductive health activist "who loved sex and she had spent 40 years seeking a way to make it better," an outcast biologist, a wealthy heiress/diaphragm smuggler and a renegade Catholic doctor. They make for an unlikely crew.

The activist, is of course, Margaret Sanger, women's health pioneer, founder of Planned Parenthood and the visionary behind the hormonal birth control pill. Sanger was the one who brought on board biologist Gregory Goodwin Pincus, who transformed his research on ovulating rabbits into the drug cocktail that would eventually allow women to have sex while avoiding pregnancy. Heiress Katherine McCormick shared Sanger's passion to separate sex from reproduction -- and had the money to fund the whole enterprise. Then there was John Rock, a Catholic OB-GYN who was recruited (despite Sanger's protests) to add an air of legitimacy and religious respectability to their project.

In Eig's telling, it's clear that each of these characters shared a drive to create safe, affordable birth control for high-minded and feminist-as-hell reasons. Each fought against the political, cultural and social mores of the time to advocate for women's reproductive autonomy, with a keen awareness that allowing women to control their fertility would open doors that had been previously locked shut. They broke laws; they made trouble; they were rebels.

But the path to realizing their feminist vision was often pretty exploitative and compromising of women's autonomy, safety and basic rights. Sanger's involvement in the eugenics movement is well-documented. Women in prisons and asylums became unwilling test subjects for the pill. Young medical students and nurses were forced to participate in the invasive and medically demanding trials after being threatened with grade reductions and pay cuts. The side-effects were often terrible, but there was little regard for the rights, health or safety of women in Puerto Rico who endured them. The history of the pill is, at times, a very ugly one.

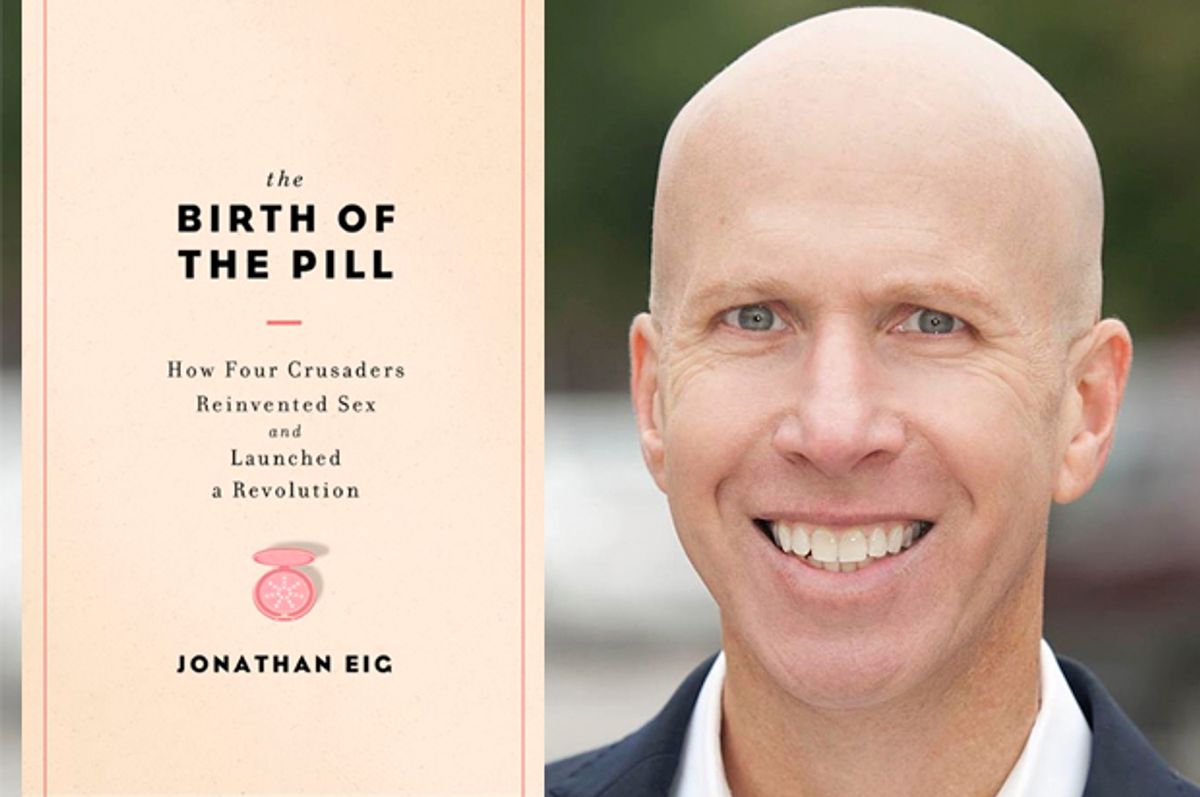

Last week, I spoke to Eig about his book, the legacy of the pill and the four crusaders he profiled, and how, when it comes to politics, birth control and the Catholic Church, the more things change, the more they stay the same. Our conversation has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Your last book was about Al Capone. How'd you get from organized crime to birth control?

As always, these are complicated things. To boil it down, years ago -- maybe five years ago -- I heard my rabbi give a sermon about the birth control pill. And he made the case that it was the most important invention of the 20th century. And my initial reaction was, "Baloney, it couldn't be! You've got airplanes, television, computers!" But the more I thought about it, the more it stayed with me. When you think about the ripple effect the pill had, I think he may have been right, after all.

It changed the way men and women get along, it changed marriage, it changed opportunities for women. As I began thinking about this, it occurred to me that I had no idea how we got the pill. Who invented it? I know who invented the airplane and the computer, but I had no idea where the pill came from. It just struck me as strange that anybody would invent it. Because men were running all the drug companies back then, and there weren't very many women working in science. So how did we get the pill?

That's where my curiosity really took over. I began looking into it, and found this incredible story.

The timing of the book seems fortunate, in a way. So many of the debates about the pill that you explore in the book -- what it would mean for the family, women's autonomy, sexuality -- are conversations we're still having now, all these years later.

I was absolutely thinking all along that this remained controversial. There's always been controversy around birth control. There have always been men who are uncomfortable with women's equality. And that's one of the effects of the pill. It gives women more power, more equality. Birth control in general, not just the pill.

I don't think we've ever really settled it. And I don't think the country has ever been really comfortable with the idea of birth control. That's something that guided me in writing this book because I thought that we need to understand where we come from in order to understand where we are today.

What are some of the parallels you observed in your research? The tension between the Catholic Church and the rest of the public, the gulf between politicians' ideologies and the needs of their constituents -- these things are certainly the same as they ever were.

The striking thing to me is that when this came along, when people began pitching this and introducing the idea that we might have birth control that women could control themselves, there was a great level of discomfort -- among men, mostly -- that this would unleash promiscuity, create this sex-crazed society. And the responsibility and the blame for that was always placed on the women in these discussions. And we're still very much having that argument today. That it's OK for men to have access to Viagra and have that covered by their insurance, but it's not OK for women to have birth control because they want to have sex. There is a huge double standard.

Well this squeamishness about sex is something you get at in the book, of course. Even in how the pill was marketed in its earliest stages as a fertility treatment, when researchers were really driving at the exact opposite outcome. The prospect of separating sex from reproduction, then as now, was too controversial a sell.

The inventors and the advocates for the pill -- Sanger, McCormick, Pincus and Rock, primarily -- they were guerrilla fighters. They recognized that they couldn't take on a straight-on approach here and say, "Hey world, we've got this great new birth control device and it's going to make sex a lot more fun and give women all kinds of power."

That would have been like walking in front of a cannon. They would have been blasted out of the water. So they went about it very subtly, taking baby steps and saying, "We'll, we've got this thing and we think it works, so we're going to try it quietly. First we're going to try it by giving it to women who are undergoing fertility treatment," which is incredibly ironic but fairly brilliant. Then they tried it in mental hospitals, then finally, in big clinical tests, they went down to Puerto Rico, where they were pretty much off the radar.

[Once it hit the market], women figured out that this new drug, which was really only approved for menstrual regulation, worked as an oral contraceptive. Women started going to their doctors and asking for it. There was a sense of desperation because they felt like they had no control over their bodies, and here was an answer. So there was an incredible clamor for it, even before the FDA declared it safe for birth control.

Among the four people you profile -- Sanger, McCormick, Pincus and Rock -- there is a real sense of being mission-driven, that they believed the invention of the pill was about liberating women. But, at the same time, they engaged in a lot of wildly unethical deceptions and coercions -- all of which targeted women. They misled women in the trials, they coerced or outright forced women -- women in institutions and prisons, nurses and medical students -- to participate in the studies. In Puerto Rico, they seemed to believe they didn't have to be accountable to anyone about their research methods -- especially not the Puerto Rican women in their trials. The pill, like Sanger herself, has a complicated legacy. Being both in the service of women, but brought about at the expense of women, particularly women who were already marginalized.

They conformed to the ethical standards of the 1950s, but that is not saying much. Pincus, at one point, said to the officials at [the pharmaceutical company] Searle, "Yeah, there may be some strokes. Women may suffer serious side effects. But unwanted pregnancies are far more dangerous than anything we could throw at these women with this pill." So the idea was, stopping unwanted pregnancies saved lives, even if there were casualties along the way.

Sanger and all of these characters were pragmatists. They were willing to take on allies who were problematic -- Sanger, certainly, got in bed with the eugenicists and expressed racist beliefs, even though her racial attitudes were very complicated and she did some good work with clinics in Harlem and had W.E.B. Du Bois on her board. All of these things are complicated, but I think the bottom line was that she believed a pill would give women power. It would allow them to enjoy sex. It would allow them to approach something like equality with men. If it meant that she had to form these unholy alliances along the way, then she was willing to do that.

Rock is a particularly interesting character today considering the ongoing tension we see between the church and the use of the pill. He seemed to be a credibility bridge-builder. This good Catholic doctor who was able to put a very respectable face on the project.

I love John Rock because he was always true to himself. He loves his church, he loves his religion, he goes to mass every day. And yet he feels like the pope is wrong, that the Vatican is wrong in its approach to birth control. He has worked with women as a gynecologist and he sees that sex is an important part of happiness in their marriages. He believes that women should have the right to choose for themselves when they have children and how many they have. He really thinks that he can save the church! That he can turn them around, make them see things his way. And he comes pretty close to doing it, it's really pretty amazing.

And he was right, of course. He was saying to them that they were losing their flock, and that if they would just try to see things from the perspective of these women and be a little bit more flexible, they might keep them in the church.

A lot of theologians agreed with his way of thinking, but, in the end, the pope stuck to the old line. The rest is history. The church is still struggling with the effects of that decision.

It seems to be this "agree to disagree" within Catholicism. The overwhelming majority of Catholic women have used birth control at some point in their reproductive lives. It's one of those hidden in plain sight secrets between the church hierarchy and most Catholics.

It's really a time when people said, "I'm a faithful Catholic but I'm just not going along with this." When large numbers of Catholics started to say, "I disagree with the pope and I'm going to do things my way."

How do you interpret the legacy of the pill in the context of the ongoing political and cultural battles over women's reproductive freedom?

There are a lot of things that are applicable. In some ways, it's sad that the story is still so relevant. Women and men don't have as many options as they should for birth control. This is a right we have fought for and earned. Nobody should be able to take that away. The fact that we're having the same arguments we had back in the 50s is crazy.

Shares