One Saturday night in St. Louis about decade ago my younger son, then a teen, was driving around town with two white friends. I’m black and my husband is white, so our two sons are biracial. This particular son has his father’s straight hair and aquiline nose. His skin is brown like mine.

The friend in the back seat behind my son stuck a paint pellet gun out the back window and shot a stop sign. He didn’t see two police cars parked just ahead. The cops hustled out of their squad cars and did the “Whoa, what the 'F' are you doing?” routine. The kids were taken to the police station, the gun was confiscated, and eventually all the parents were called to come to the station.

Back up about eight years. As a young family, we usually didn’t talk about race or even acknowledge it, because at the time we didn’t see the need. Then one night at the dinner table I got my first reality check when our younger boy, who was 7 at the time, said, “Dad, I want white skin and braces. And a new first name, like Michael.”

I wasn’t sure my husband understood the breadth of this comment. Like so many suburban St. Louis white kids in the 1960s, he grew up in a racially homogenous bubble, with no black friends until he went to college. Black children in St. Louis were in a similar bubble, except they mostly lived in the city because the suburbs were still white.

Things were a lot different where I grew up, in Harlem. My family was multiracial. Schools were integrated and members of the diverse community -- white, black, Puerto Rican, Indian and more -- mingled openly, with joy and ease. I received only the occasional reminder of the color of my skin.

In St. Louis, where I settled in the 1970s, such reminders came far more frequently. A store clerk once followed closely on my heels while I browsed an upscale furniture store, as if she found me suspicious. At times waiters or supermarket clerks have avoided looking me in the eye. And on more than one occasion, repair people have rung the doorbell of our home in a predominantly white neighborhood and, when I answered, asked if they could speak to the lady of the house.

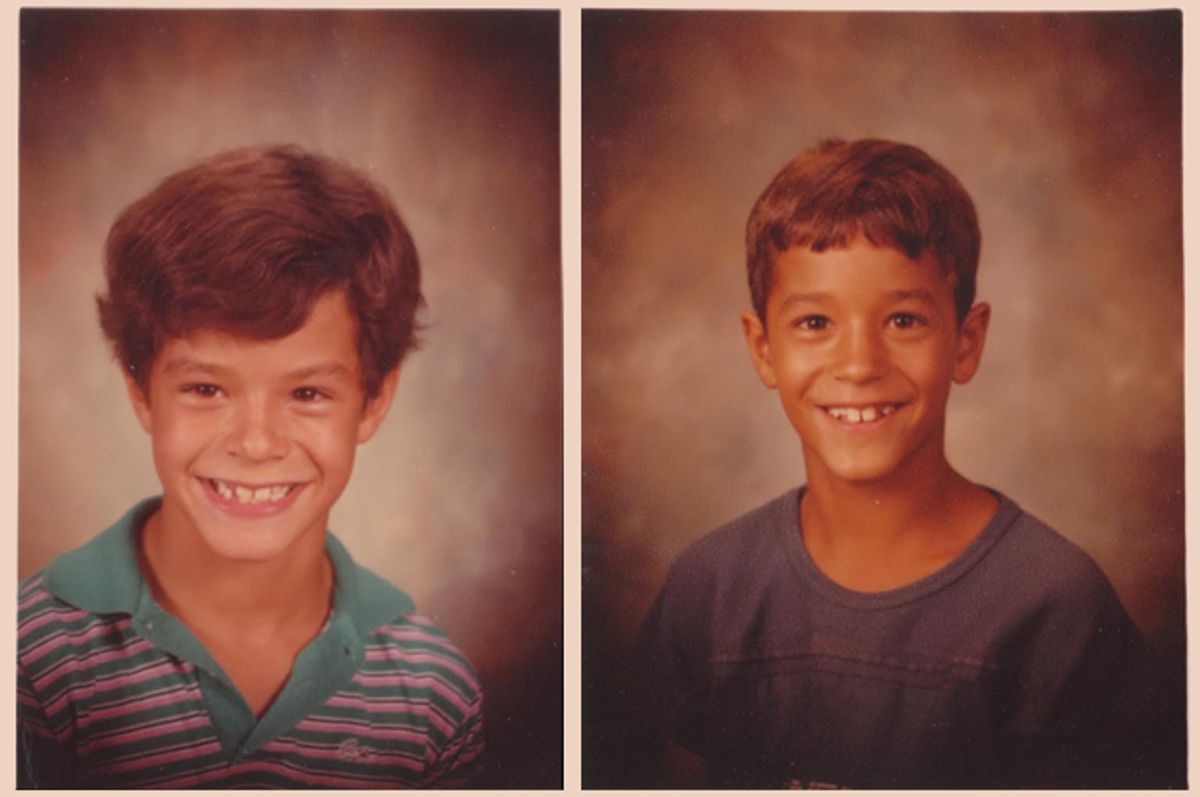

While raising my boys, I often wondered: Should I have “the talk” with them about being black? The decision was complicated by our older son’s appearance. With his curly hair and rounded nose, he has always looked more like me than his dad, but unlike his brother, his skin appears completely white. This detail had always made “the talk” seem absurd. Should I poison the well of innocence by telling his brother that he was different? I decided that wasn’t going to happen because he wasn’t different. We were a family, and they were best buddies; smart, good-looking, polite kids, and also competitive as hell.

Now, at the kitchen table, I listened as my husband laughed and said, “Everybody thinks braces are cool except kids who have to wear them. And you know what? One day when I was about your age, I told Grandpa that I wanted to change my first name. To Rex.”

Both boys sat impaled to their seats, enthralled by this story of the things we’d all change if we could. The next part, telling our younger, dark-skinned son how special, rather than different he was, came easily. A crisis ended without words like black, white, or race ever entering the conversation. Still, I continued to worry as both of my sons -- but especially the younger one with darker skin – got older and faced heightened scrutiny about their appearance.

Time moved on, and the boys grew comfortable in their skin, maintaining their racially neutral view of themselves and the world. I, too, wanted to believe the world was colorblind, but with my Harlem background and the reminders I was often dealt in St. Louis, I couldn’t help worrying as these little boys grew to the size of men and started venturing out on their own. One night when we were all at the ice rink, a kid called my eldest the N-word because he knew I was his mother. My son decked him and got thrown out of the game.

Then came the phone call about the paint pellet incident. My husband went to the station and handled everything. About 10 days later, we all appeared in juvenile court to learn what the punishment would be. The white kid with the gun was most culpable and had a later court date, but they all got into trouble.

While my husband and one of the other fathers talked to the lawyer, a different policeman said to my son and me, “If I saw one of these paint pellet guns sticking out a car window, you don’t know how close I’d be to shooting you.”

I’ve tried not to think too deeply about or analyze what might have happened if the cop had seen the gun sticking out of the car, or why he chose to say what he did. I’ve also tried not to think too much about why he didn’t wait to say this in front of the white boys who were there that day, and their parents.

Recently I asked my son if, as an adult, he ever gets hassled by the police -- whether in the cities he moved off to, New York and L.A., or here in St. Louis where he grew up. “No,” he answered. “The cops see me as neutral.”

Even having succeeded in raising him with this racially neutral vision of himself -- which in an ideal world would be perfectly appropriate -- I continue wondering if I did the right thing.

Shares