The word "troll" -- when referring to an Internet provocateur or harasser -- has become irretrievably broken. At the very least, we have no working definition of the term, and few helpful ways to cope with the wide range of behaviors it's used to describe. Everyone who says "troll" seems to bring his or her own particular and painful experience to the table, and far too often that experience prevents us from clearly judging any given accusation of trollery. Here's how this problem exploded in the corner of the Internet devote to books over the past week.

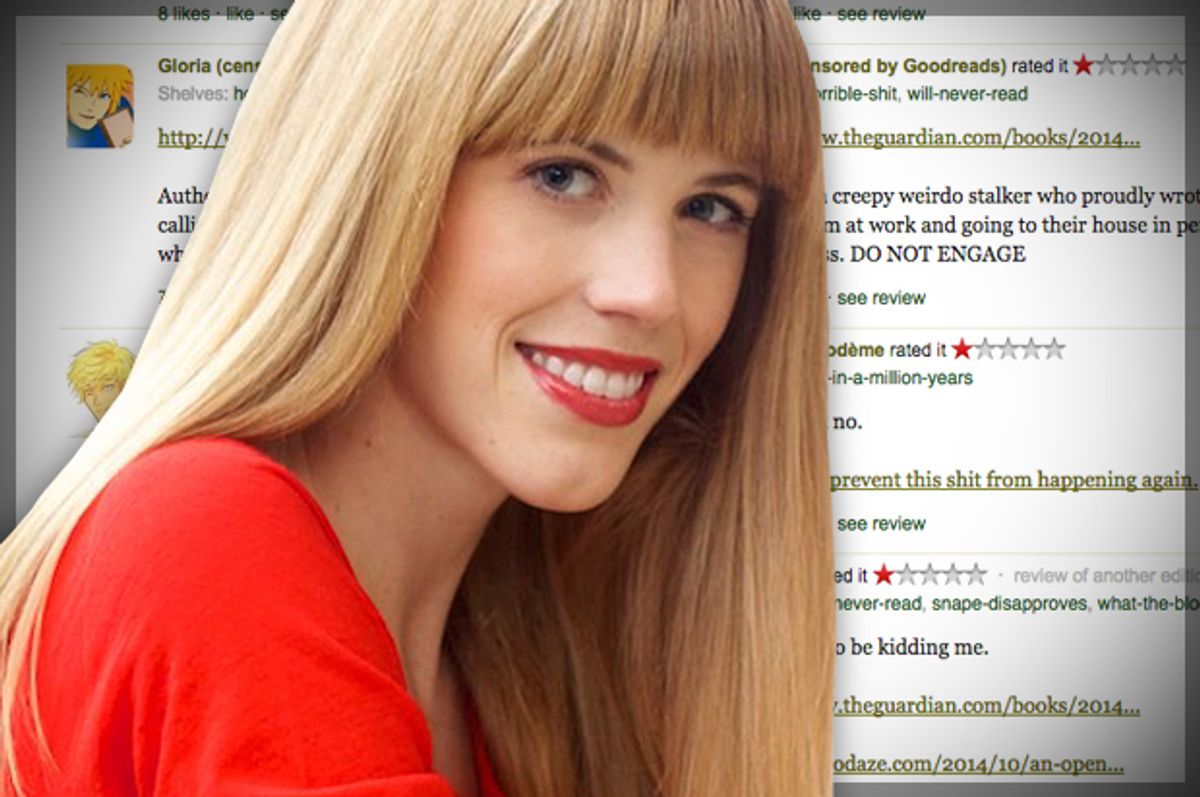

On Friday, a YA novelist named Kathleen Hale published a personal essay in the British newspaper the Guardian, recounting her obsession with someone who had criticized her first book harshly. Hale admits to combing the Internet for information about the woman, a blogger who, while reading Hale's book, posted a derisive running commentary to Goodreads, an enormous social networking site for book lovers. Hale confesses that she scrutinized the woman's Instagram feed and Facebook page, as well as engaging in subterfuge to obtain the blogger's home address. In doing so, she discovered indications that the blogger's actual identity is quite different from the one she presents online. Then Hale drove to this woman's house and knocked on her door. Receiving no answer, Hale later called the woman she suspected of being the blogger at work, twice: the first time pretending to be a fact checker and the second under her real identity, trying to get the woman to admit that she was, as the Guardian headline put it, her "number one online critic."

Responses to this story fell into three general camps. One merely found it a freakishly fascinating yarn about two people with a dysfunctional relationship to the Internet; Hale makes largely unsubstantiated claims that the blogger had triggered a "ripple effect" of "vitriol" throughout Goodreads in opposition to her book and that the blogger had mocked Hale in a series of posts on Twitter. Bloggers, reviewers and Goodreads members were appalled by the Guardian essay, and accused Hale of stalking a reader who had done nothing more than give her a bad review. They also condemned the Guardian for publishing the blogger's (maybe) real name. With authors this nutty running around, the reviewers maintained, it's little wonder that many of them prefer to blog or review anonymously or behind the screen of a false identity. Lastly, there were also plenty of authors who cheered Hale on for "exposing a troll," and for confronting, in the words of one supporter, "a typical online bully hiding behind anonymity."

Even Hale doesn't defend her own conduct, describing it as "stalking" and calling her trip to the blogger's home "a personal rock bottom" and "the biggest breach of decency I’d ever pulled." That's Hale's shtick, a "Yep, I'm crazy" self-mortification that simultaneously flaunts and deplores her own actions. In similar autobiographical essays, she's written, "I never look for things to grab me. They just do, and once they do, the obsessions usually continue until I'm so sick of them – or of myself for enacting them – that suddenly, and with a sense of great relief, I'm repulsed." Hale's online writing is a queasily absorbing melange of recurring themes: violation, accusation, online "stalking," retaliation and exposure.

Hale is a gifted storyteller, able to spin the account of her pursuit of the Goodreads blogger into a tale that superficially resembles a confession of squicky and profoundly regretted personal folly. Many casual readers found themselves rather sympathetic to her; who, after all, hasn't dreamed of confronting an elusive and unfair online attacker? We all have our trolls. In a 2013 piece for Thought Catalog, however, Hale recounts seeking revenge, at age 14, against a girl of the same age who had accused Hale's mother of sexual abuse. (This charge was dismissed, but not before it and Hale's mother's name were published in the local newspaper.) Hale followed the girl into a movie theater and poured a bottle of hydrogen peroxide over her head. If the Goodreads blogger had followed Hale's Internet activity even half as closely as Hale followed hers, then she knew about the bleach incident and had good cause to fear her unexpected and very unwelcome visitor.

There's a long history of aggressive author responses to negative reviews. Before the advent of social media, for example, the novelist Richard Ford was notorious for spitting on one reviewer who'd panned his book and for mailing another reviewer a copy of her own book into which he'd fired several bullets. The latter victim, Alice Hoffman, is a novelist herself. Hoffman in turn lost it when a critic reviewed one of her novels tepidly and posted the reviewer's home telephone number to Twitter, urging her fans to call up and complain. It's not the Internet that causes such outrageous carryings on, but technology, of course, has shortened the period between impulse and execution, providing much less opportunity for better judgment to intercede. Not all authors are crazy and vindictive, either, but a surprising number seem to be, and there are fewer barriers than ever to prevent them from venting their spleen.

If the horrified response of book bloggers and Goodreads reviewers to Hale's confession is well-founded, what about the authors and other commentators who felt that Hale was holding a troll accountable for her misdeeds? Most of these did not approve of the author's visit to the blogger's home, but they still sympathized with her frustration at being unable to effectively challenge someone she believed had treated her work unfairly. Still other writers -- those unfamiliar with the well-networked world of YA authors, reviewers and bloggers -- expressed bafflement that anyone would bother to look at their Goodreads reviews in the first place, let alone become so fixated on one of the people who writes them.

It helps to understand Hale's case in the context of that particular literary subculture. The YA market is one of the most successful sectors of trade publishing right now, in large part due to how interconnected its readers (and authors) are. YA fan networks, most of them online, have played major roles in the explosion in blockbuster YA book series like "The Hunger Games" and Veronica Roth's "Divergent" trilogy. Publishers encourage authors to have a social media presence in the communities fans frequent, and self-published authors are often advised that grass-roots enthusiasm is the only thing capable of springboarding them from obscurity to the kind of sales that mean finally quitting their day jobs.

As I reported extensively last fall, all sorts of utopian predictions about a new era in publishing -- one in which authors and their readers intermingle digitally -- have come to grief in the YA and romance realms of Goodreads. To (radically) summarize: A robust community of enthusiastic and outspoken YA readers formed there several years ago, becoming one of the few places self-published authors could hope to get wider exposure. Several of those authors proved incapable of handling the negative reviews their books received and intruded (often enlisting the help of friends) into the reviewers' discussion threads.

The authors picked quarrels with their critics and bombarded them with emails demanding that reviews be deleted or changed. The reviewers banded together to retaliate, descending on the book pages for "badly behaving authors" and posting scathing one-star reviews, whether or not they'd read the book in question. A creepy website called Stop the Goodreads Bullies -- uncritically cited by Hale in her essay -- was formed by anonymous parties to "expose" and revile the most active reviewers in this group. Eventually, Goodreads introduced a policy dictating that reviews referring to an author's behavior would be deleted, but things have barely cooled down since.

By now, both sides have accused each other of trolling, bullying, harassment and doxxing (the publication of personal information online). Employers have been contacted and urged to fire the combatants. People's families have been written about in disturbing ways. Each side is convinced that it is far more sinned against than sinning.

For if authors can come unhinged, so can fans. Charlaine Harris and Veronica Roth have both received violent threats from readers displeased with the way these authors concluded popular, long-running series. Some of the strategies that Goodreads reviewers developed to repel meddling authors have come to resemble an overactive immune system that pounces on the slightest infraction and crushes the (often merely clueless) perpetrator with extreme prejudice. Firsthand experience of this is why many authors were so ready to believe Hale's complaints of being trolled even though she offered no evidence or concrete details about what this purported trolling involved.

Reader attacks can take the form of scores of one-star Goodreads reviews, often tweeted at the author to make sure they're noticed, and menacing emails that may or may not originate in the Goodreads community. (Several traditionally published YA authors contacted me to say that they and their fellow novelists often felt targeted by such harassment but would not comment on the record for fear of further reprisals.) The community's discussions have their own particular house style, an adolescent, trash-talking swagger that can seem ominous to outsiders. "It is now my sacred duty to find this bitch and kill her dead," wrote one commenter of the author Maggie Stiefvater on LiveJournal (a blogging site). Do I think the commenter actually intends to assault Steifvater? No, but given the high moral dudgeon these reviewers fly into whenever an author handles issues of harassment, violence or abuse incorrectly, it does seem pretty hypocritical.

It's worth pointing out that both sides in this conflict feel disadvantaged. The reviewers tend to see successful authors as culturally powerful. (So much of the Internet's nastiest manifestations come from those who view themselves as underdogs striking back in the only way they can.) Authors, having been told that only word-of-mouth can sell a book, see the worst-case scenario playing out online and believe the reviewers capable of "ruining" their careers. A fellow writer invoked the specter of such sabotage when Hale called her up for info on the bloggers. "DO NOT ENGAGE," the woman instructed Hale. "You’ll make yourself look bad, and she’ll ruin you." Whether any book or author has truly been ruined as a result of being targeted by organized groups of disgruntled readers and reviewers seems doubtful, but Hale certainly did succeed in making herself look bad.

Compounding the paranoia and outrage on both sides is the tendency for social media to act like an alchemist's alembic, distilling the complicated thoughts and feelings of individuals into generic expressions of self-righteous indignation. It's not the concision of, say, Twitter that causes this -- it's perfectly possible to express ambivalence in 140 characters -- but a hectoring pressure toward pro forma piety and groupthink from small circles of like-minded people who want to present a united ideological front to the world.

That doesn't make them wrong -- Hale seems to be a bona fide nutcase and some anti-author campaigns can be genuinely disturbing -- but it does make many of them disingenuous, defensive and counterproductive. If you're going to assert that, say, misogynistic online comments provide legitimation for actual death threats made against feminist writers, then why shouldn't the people who post nasty stuff about prominent authors be held at least a little bit culpable for the death threats made against writers like Harris and Steifvater? Some authors, on the other hand, want the benefits of a passionate, engaged community of readers without accepting that such a community must also be free to hate their work. Perhaps most insidious of all is the spectacle of genres that profess to champion the strength and value of girls and women descending into the most stereotypical forms of toxic "feminine" behavior: cliques, backbiting, venomous gossip, name-calling, sneakiness and whispery passive-aggressive scheming. Sometimes the worst troll of all is the one in the mirror.

Further reading:

Kathleen Hale describes stalking a Goodreads critic in the Guardian

Hale recalls attacking another girl at age 14

A Storify account of responses to Hale's essay

Goodreads: Where readers and authors battle it out in an online “Lord of the Flies” by Laura Miller for Salon

How Goodreads could lose its best readers by muzzling them by Laura Miller for Salon

Shares