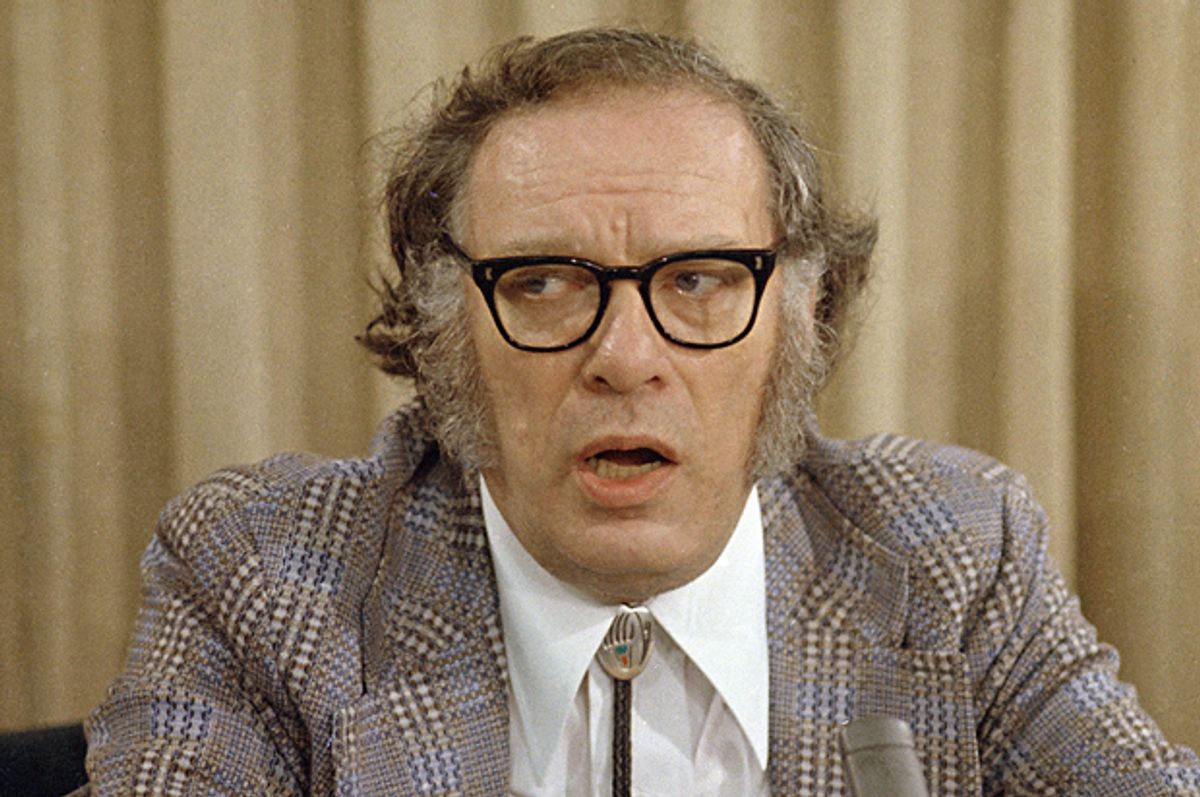

In 1959 the prolific author and professor of biochemistry Isaac Asimov wrote an essay about the formation of ideas and how to spur creativity. Fifty-five years later, the essay was found by Asimov's friend, the scientist Arthur Obermayer, and published by MIT Technology Review.

The essay was the author's sole formal contribution to a research group funded by the Advanced Research Projects Agency "to elicit the most creative approaches possible for a ballistic missile defense system."

Asimov eventually left the group as he did not want to be privy to classified or secret information, according to Obermayer. This essay on creativity, however, remains, and in the face of surmounting obstacles it remains as relevant as ever.

"How do people get new ideas?" Asimov muses. Asimov himself wrote and edited more than 500 works and was famed for his science fiction novels. One can surmise that he was not short on ideas -- or a method of cultivating creativity.

Asimov instead looks at how Darwin and Alfred Wallace came up with the theory of evolution via natural selection, and breaks down the essentials of creativity. Just as important as Darwin and Wallace's background and travels was their ability to make connections between granules otherwise detached:

"Obviously, then, what is needed is not only people with a good background in a particular field, but also people capable of making a connection between item 1 and item 2 which might not ordinarily seem connected."

The "cross-connection" Asimov explains is specially cultivated from certain personality and societal factors.

"Making the cross-connection requires a certain daring. It must, for any cross-connection that does not require daring is performed at once by many and develops not as a 'new idea,' but as a mere 'corollary of an old idea.'"

"It is only afterward that a new idea seems reasonable. To begin with, it usually seems unreasonable. It seems the height of unreason to suppose the earth was round instead of flat, or that it moved instead of the sun, or that objects required a force to stop them when in motion, instead of a force to keep them moving, and so on."

"A person willing to fly in the face of reason, authority, and common sense must be a person of considerable self-assurance. Since he occurs only rarely, he must seem eccentric (in at least that respect) to the rest of us. A person eccentric in one respect is often eccentric in others."

Despite writing "that as far as creativity is concerned, isolation is required," Asimov does write at length for the rest of the essay on how best to foster creativity in groups -- five is a good number, he suggests. To cultivate group creativity he believes the perfect human petri dish is one of ease and relaxation:

"But how to persuade creative people to do so? First and foremost, there must be ease, relaxation, and a general sense of permissiveness. The world in general disapproves of creativity, and to be creative in public is particularly bad. Even to speculate in public is rather worrisome. The individuals must, therefore, have the feeling that the others won’t object."

Asimov wrote this before radical changes were made to office structures, before Steve Jobs and Pixar, before Silicon Valley and the culture of start-ups were perverted and mass marketed. His ideas seem far before his time.

Yet his essay was published at the exact right moment -- a moment when our society may need to be reminded of this simple prescription. We need to shed some of the manic hype for the "next thing" and take a moment to make true, daring new connections. To be informed and eccentric.

This line stands out: "It must, for any cross-connection that does not require daring is performed at once by many and develops not as a 'new idea,' but as a mere 'corollary of an old idea.'"

Shares