In my colleagues’ view, examining the racial impact of legislation only perpetuates racial discrimination. This refusal to accept the stark reality that race matters is regrettable. The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race, and to apply the Constitution with eyes open to the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination. As members of the judiciary tasked with intervening to carry out the guarantee of equal protection, we ought not sit back and wish away, rather than confront the racial inequality that exists in our society. It is this view that works harm, by perpetuating the facile notion that what makes race matter is acknowledging the simple truth that race does matter.

-- Justice Sonia Sotomayor

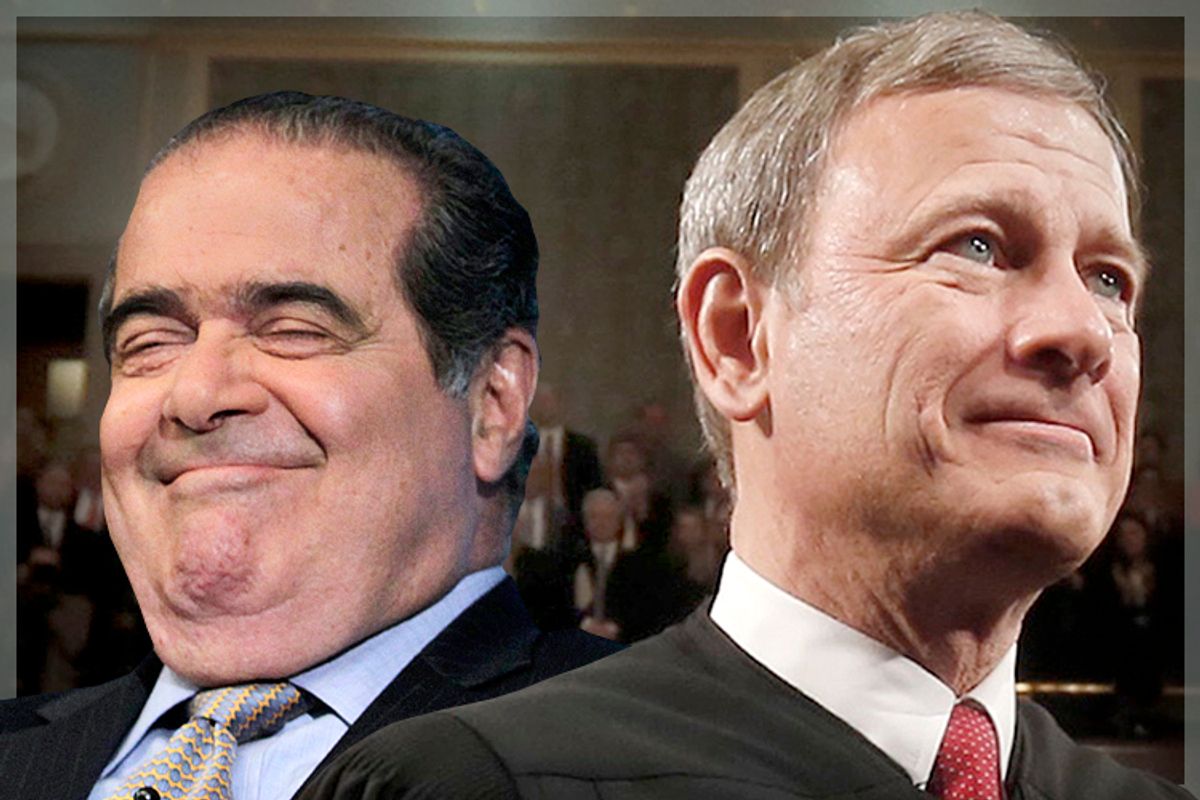

The majority on the Supreme Court, as Justice Sotomayor observed in her dissent in Shuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, where the Supreme Court upheld the right of voters in Michigan to ban affirmative action in university admissions, are against considerations of race to solve the problems of racial inequality in our society. How are we to act effectively on the obstacles confronting African-Americans, if we cannot target legislation and programs aimed at this population?

This is a critical question facing this society at a time when all of the indicators -- incarceration rates, healthcare, education, employment, wealth, family cohesiveness, mental health -- are trending in the wrong direction for African-Americans. How did we reach the point that it is impossible to assemble a coalition of Americans regardless of their political persuasion to address problems among the African-American population that are clearly traceable to the sequential and compounding effects of slavery, Jim Crow segregation and economic disenfranchisement?

It is as Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal concluded in "An American Dilemma," a 1944 study of the so-called Negro problem in America: American whites have degraded African-Americans, and then held them in contempt for their degradation. Although a declining number of white Americans think this way today, personal and institutional racism continue to bedevil American society.

The term “affirmative action” has been made into a pejorative and has been associated with racial preferences, and quotas. What began as a modest compensation for the theft of African-American labor and debasement over centuries, has morphed, in the minds of some, into programs that discriminate against whites. Further, opponents of affirmative action see any effort to apply goals of diversity as an attack on the meritocratic ideal.

A meritocracy is an idealized society where the benefits of the society are distributed on the basis of individual merit. Clearly, one can find this in American society; however, merit in its broad application is overwhelmed by systemic effects of race and class. The lack of diversity, in many instances, and rising economic inequality are both the result of this fact.

It is understandable that pride has moved some Americans, including a minority of African-Americans, to envision a kind of American individualism, which might have worked in their own lives, as effective public policy, and are not supportive of race-conscious policies. Make no mistake, individual initiative is important, but cannot substitute for civic and governmental action.

Given the deep opposition to compensatory programs by large numbers of whites, one would conclude that the history of black oppression is not understood, or there are serious barriers to the development of empathy, compassion and fairness. Education can fix the lack of historical knowledge; however, racial sensitivity, which cannot be legislated, is a more difficult challenge.

The broad consensus we need to solve racial problems will occur when we acknowledge that, like cigarette smoking, racism is cancerous. Similarly, it destroys lives. Once we recognized and accepted the medical effects of nicotine, we waged an effective campaign against smoking, and made it individually unhealthy and socially unacceptable to smoke in public places. Likewise, we should wage an effective public campaign against the twin psychoses of racism and color prejudice so that they will become recognized and accepted as individually harmful and socially unacceptable.

Additionally, armed with historical and current facts, race-conscious individuals should join the fight to undo the ban on affirmative action in states that have instituted bans, and work against those who are trying to enact new bans. Public education should be strengthened, including enacting programs to improve the achievement of African-American students from preschool through high school. Colleges and universities should step up their efforts to recruit and retain increasing numbers of African-American students. Federal, state and local governments should vigorously attack poverty in the African-American community. Private companies, small and large, should re-access their commitment to diversity, and aggressively seek to hire African-Americans in significant numbers.

African-Americans are like the “canaries in the mine” of our fragile democracy. Unchecked police and judicial power, voting rights infringements, income inequality, persistent unemployment and educational dysfunction are endemic in the African-American community, and are warning signs that our democracy is in danger. If citizens of African descent are oppressed and are not allowed to participate fully, it is our democratic ideals that will be undermined.

Shares