The phrase was always historically ignorant and glib enough to deserve little more than contempt, but after the past six years — during which the nation's first African-American president saw his approval among whites sink like a stone, despite his assiduous efforts to avoid most discussions of race — I think it's fair to say that only bigots and the hopelessly deluded still talk about "post-racial America."

Events this summer in Ferguson, Missouri, have been the most visible pieces of evidence that we're living in a post-post-racial country. But in a recent brief on economic and racial inequality — "The Equity Solution: Racial Inclusion Is Key to Growing a Strong New Economy" — the progressive organization PolicyLink puts the unpleasant reality in even starker relief. If the U.S. is able in the coming years to find a way to bring people of color more fully into the economy, PolicyLink finds, the economic benefits for all could be enormous. That'd be great, obviously; but the dramatic way true equality would change our economy is also an indication of just how much progress there's still left to make.

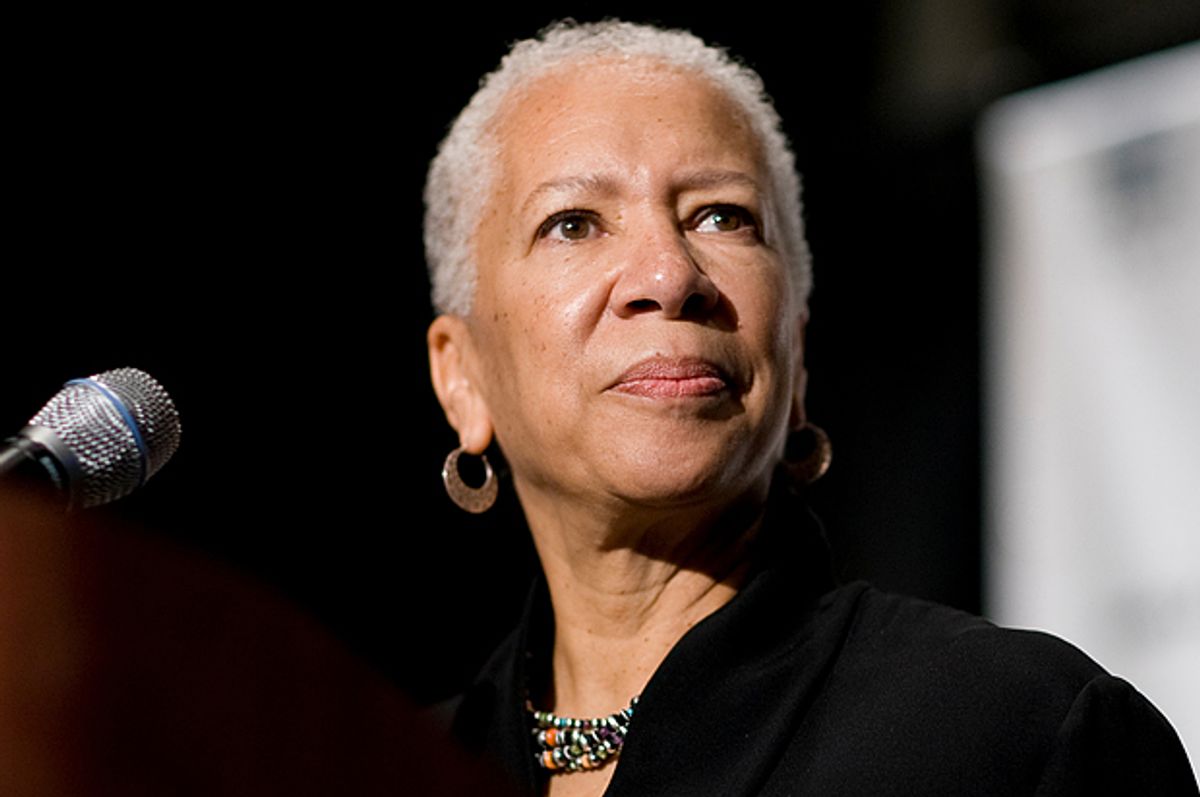

Recently, Salon called PolicyLink founder and CEO Angela Blackwell to discuss the brief as well as why she believes the future of people of color in America and the future of the middle class in America are one and the same. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

Could you tell me a bit about the brief? What did you find, and why is it so important?

The Equity Solution brief provides important new data that has been missing from the discussion about equity and America’s economic future. It does this by estimating the economic benefits of racial inclusion for the largest 150 metropolitan regions, all 50 states, the District of Columbia and the nation as a whole.

This is very important because of the changing demographics. We’re rapidly becoming a nation in which the majority will be people of color by 2043, but by the end of this decade the majority of children will be people of color, and by 2030 the majority of the young workforce will be people of color. As a nation, we have to come to grips with the fact that what happens to people of color in terms of opening up opportunity, making sure that people are ready for work, ready for leadership, ready to pursue their entrepreneurial skills — that the future of the nation depends on that opportunity being accessible and being taken advantage of.

We often think that the equity agenda — which I think of nothing more as just and fair inclusion into a society in which all can reach their full potential — as being a moral imperative. It’s become an economic imperative. This research that shows that if we achieved equity in terms of income (which does not mean that everybody has the same income, it means the income curve for people of color being the same as the income curve for people who are white, so people in the lowest 20 percent are making the same, people in the middle, people in the highest 20 percent), if those income curves were the same, the nation’s economy would be $2.1 trillion larger. That can also be seen in the 150 regions and it is very important for the well-being of the nation, that we both understand the economic imperative and the direct benefits that we could gain.

Linking racial equality and economic equality makes sense, but it's not something you often hear being promoted in more mainstream or establishment-friendly places. How do you respond to people if and when you come up against resistance or skepticism — or simple confusion, since making the link is not especially common?

One of the things I often say is that if people of color don’t become the middle class there will be no middle class in this nation. Not only are we becoming a nation in which the majority will be people of color, but the majority of young people will be people of color. Right now, 46.5 percent of all children under 18 are children of color, but 80 percent of all those over 65 are white. The median age among white people is 42; the median age among Latinos, the fastest-growing population, is 27.

We have to understand that as we become a nation of mostly people of color, that we have mostly people who would be the parents, the young earners, the young entrepreneurs. Those are the people of color who we have to make sure can be the middle class. When we think about some of the work of Raj Chetty and Emmanuel Saez, who are looking at social mobility in this country, they’ve pointed out that social mobility is very much tied to class and geography. If you’re born into a family that’s low-income you’re very likely to stay there, and if you’re born in certain areas of the country — particularly the South — you’re very likely to not have much social mobility.

Those things can also be talked about in racial terms. In the South, what we see is our inability as a nation to deal with race, and so segregated communities and disadvantaged people of color disadvantages everyone. We have to get over this holding some people back because what it means is that we’re holding everybody back. We’re not investing in a robust public education system, not invested in a robust infrastructure that could connect regions to the global economy.

This notion of being born into a certain area — we know that people who are Latino and African-American are disproportionately poor and low-income, so we have to create more pathways out of poverty, not just in terms of people who are poor having pathways out of poverty but people who are poor because of the way we have racialized opportunity in America. We cannot separate the nation’s dire need to have a strategy for a vast and stable middle class from the nation’s dire need to finally have strategies that deal with the legacy of racism and the continuing impact of racism in America.

I'd imagine this will only get more pressing as time passes, but you're also going up against the post-racial America myth.

PolicyLink has been beating this drum about the national and the economic imperative to get over racial bias and aggressively open up opportunities for the sake of it being the right thing to do and for the sake of the nation. We have been beating that drum and we have been heard by some in that others are starting to beat that drum as well. The nation as a whole, though, has neither heard the narrative nor has it taken it in and owned it, and it is very important that we keep building this message so that the American people can begin to align the policies of the nation with where their hearts would like to go.

I do believe that many in this nation would like to get over racism. I think it’s one of the reasons that it’s such a hard conversation to have. People don’t want to talk about it. It embarrasses them, they feel ashamed, they feel that there’s nothing they can do about that that lingers once the legal barriers have been removed, but we have to see that removing those legal barriers did not create a level playing field. The extraordinary incarceration of black men is a scandal; the extraordinary poverty for black and Latino children is a scandal, so we have to keep talking about this so that we can get policymakers and leaders and the American people comfortable with understanding that the moral imperative exists but it’s an economic imperative now. If we don’t get it right, the fate of the nation is not promising.

The other thing, though, is that after President Obama was elected and people were dreaming and hoping for a post-racial America because people would be so glad to put this behind them ... we neither saw superficial nor deep changes in that period. We didn’t see the superficial changes: Housing segregation is as bad as ever, the schools are more segregated than ever, neighborhoods are very segregated; we haven’t seen a change there.

In the deep recession that was also right there when the president came in, those who had come in late to seeking prosperity were hit hard and have yet to recover. Black and Latino families lost more than 50 percent of their collective wealth because of the housing bubble, and there has been no assertive strategy to help them get it back. When families lost homes after the Great Depression in the '30s, the whole effort was to get people loans and build houses and help people get back. The approach now is just the opposite, making it harder to get a loan, keeping people out of being able to build that asset. We have to understand, we need for those who were hit hardest by the housing crisis to be able to find a way into home ownership and stability.

On the schools issue, we’re pulling back from public education rather than stepping up. On higher education, it is just as bad. Here’s a data point: By 2020, 47 percent of all jobs in the United States will require at least an associate’s degree. Only 28 percent of black people have it, 28 percent of Latinos, and only 15 percent of foreign-born Latinos. We need to understand that public education now needs to at least go through to community college, not just because we want people to have an education -- which we certainly do -- but the economy requires it, and that will mean investing in the very young people who we are placing at a disadvantage because of our failing public school system.

So not only are we not post-racial, but we’re in worse shape, in many ways, because of the Great Recession. Our inability to move anything through Congress has really made the aspirations that I think the president came in with and has tried to move very hard, to be able to move forward, to get the resources to the neighborhoods and the communities and the geographic areas that need it most.

What would you need to hear from policymakers before you believed that they were really taking the confluence of the economic and racial injustice problem seriously?

Several things. I’ll speak the obvious ones: continuing to reform the healthcare system so that we really eventually will have universal health coverage for everyone. That is very important; it eats up so much of the wealth of people not to be able to have that as part of what the government provides.

The next thing is, this effort to provide universal preschool education has great promise. We know that the most important thing that we can do is to make sure that children start school ready to learn. Having that with real momentum, both at the federal level and in states is very important. We need to step that up and we need to make sure that those resources not just get into all communities but that the early childhood programs are of high quality -- and the poorest children need high quality more than anything else.

This effort to reform the criminal justice system, get rid of three strikes in California, get rid of the unfair drug laws, make sure that we are not just taking men out of families, out of communities, and locking them up for reasons that really cannot be justified when they’re not serious crimes, when there’s no violence involved, [is also important]. These petty things that people have been criminalized for, and then kept from being able to return to their communities and get jobs and vote and participate because they have felony records — the movement to do something about that is extraordinarily important.

Shares