President Obama and Neil deGrasse Tyson recently held a joint press conference in which the former proclaimed the nation’s dire need for more English majors (“because our national security depends on it”), while the latter performed a colorful soliloquy on the relationship between the celestial bodies Jupiter and Io.

Of course this didn’t actually happen and never would, not because Neil deGrasse Tyson couldn’t pull off a fine soliloquy, but because the idea that the humanities don’t matter is perhaps the one thing Democrats and Republicans can agree on. Few, if any prominent U.S. politicians would be caught defending the humanities in public. “The humanities are useless” and “the humanities are in crisis” are now truisms on the order of “pizza is delicious.”

Yes, of course, pizza is delicious. What are you, crazy? Of course the number of humanities majors is down, of course William Deresiewicz is concerned that the souls of college students are going uncultivated, and of course a humanities degree doesn’t bode well for your ROI. Fifty grand a year to major in history? As Congressional Republicans say, who’s gonna pay for that?

Those of us with a vested interest in the humanities certainly have reasons to be concerned; but if we move past the hand-wringing for a moment and examine this crisis of the humanities, it becomes clear that the crisis doesn’t actually belong to the humanities at all.

In fact, one of the most valuable lessons of humanistic inquiry — the ability to think capaciously, akin to what historians David Armitage and Jo Guldi recently identified as long-term thinking — reveals for us the extent to which we’ve been misled by data on the humanities crisis. In particular, a focus on the declining number of humanities majors distracts us from the fact that humanities enrollments — students majoring in whatever who take humanities credits in college — have remained quite strong. A recent American Academy of Arts and Sciences study on enrollments finds that students who graduated in 2008 actually earned more credits in the humanities than in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math).

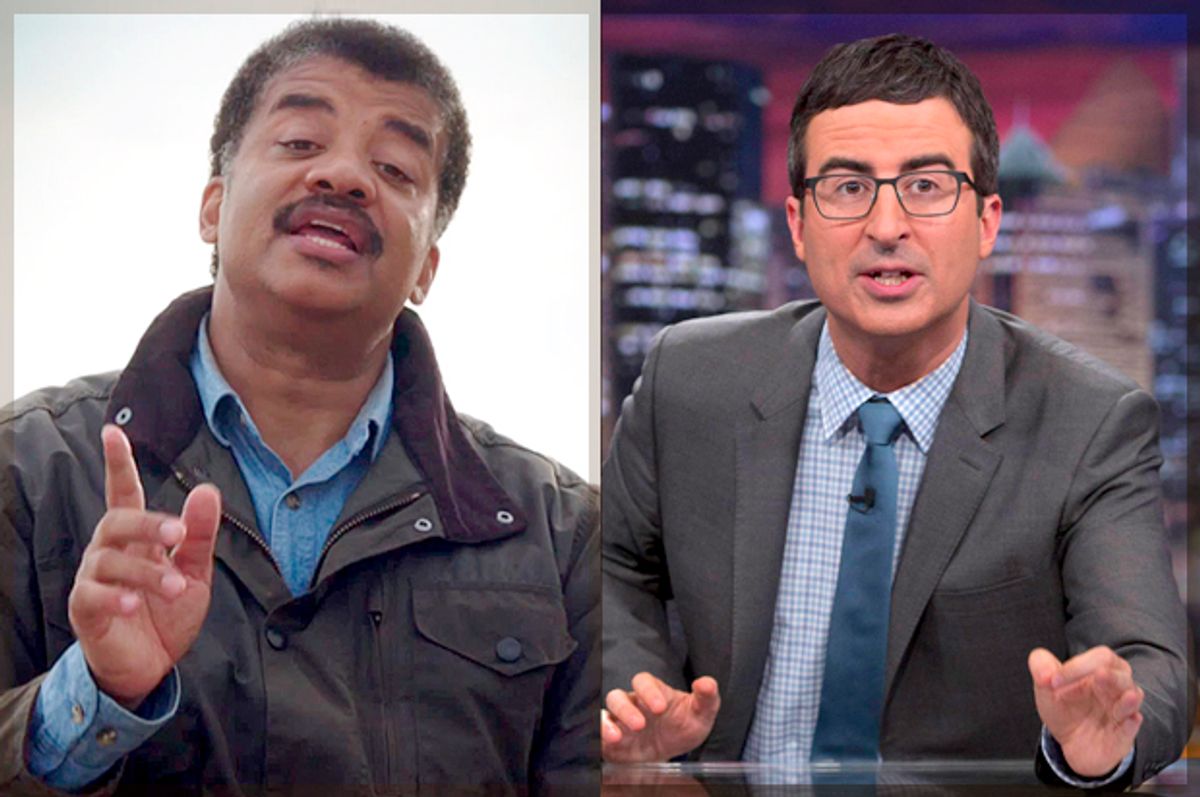

My experience at Georgetown University reflects as much: Most of the students in my English classes are not English majors, though enrollments in English classes remain strong at the University. Further, my non-English-major students are actually pretty interested in literature, history, philosophy and art. For so many of them, the opportunity to take a humanities class between the abundant requirements of their more “vocational” majors in the schools of business or foreign service is a welcome chance to cultivate marginalized interests and think critically about some very germane topics. For example, everyone interested the role of women in science today should know about Margaret Cavendish, one of the only women to publish scientific writing during the 17th-century Scientific Revolution. Anyone interested in knowing how Stephen Colbert, Jon Stewart, or John Oliver set up their compelling comedic arguments would find a breakdown of Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” both illuminating and useful.

Indeed, students maintain interest in such material both within and beyond the classroom. The average young adult might rather lounge on a futon and watch Netflix than sit up at a desk in my classroom and analyze “The Rape of the Lock”; but as classes go, and enrollments show, Pope is pretty puissant. Perhaps this is part of why language from Pope’s poetry, like “fools rush in,” “a little learning is a dangerous thing,” and “to err is human, to forgive, divine” remains with us after all this time.

So, no, the humanities per se are not in a death spiral, neither by raw enrollment figures nor by widespread interest in the kinds of subject matter and questions of value that humanities classes examine. The real crisis in the humanities is not of the humanities. We haven’t become a nation of philistines with decreased interest in humanistic inquiry; we’ve become a nation with increased anxiety about taking interest in anything other than making money.

College students feel this anxiety when their prospective employers knowingly hold entry-level job interviews and recruitment events throughout the academic year, forcing students to choose between crucial job opportunities and “priority” academic responsibilities (even when missing class or turning in assignments late can jeopardize the high GPA that employers want to see). More broadly, however, our entire U.S. education system, from the ground up, is reeling from the effects of transforming education from a publicly funded public good to just another “growth industry.” Growth industries don’t have time for the humanities any more than they have time for impoverished grade-school students who don’t boost test scores, or teacher unions seeking labor standards, or adjunct faculty with no health benefits educating America’s Next Generation of Leaders.

The crisis in the humanities, then, is really just an aftershock of the widespread crisis of neoliberalism, which encumbers all sectors it throws into crisis (arts and humanities, higher education, K-12 education, the public sector) with the mantle of bearing the name and blame for the destruction neoliberalism has wrought. Thus, rising tuition rates and global economic recession invite us to interrogate the English major with questions about return on investment, but this all becomes the English professor’s fault for not being “relevant” enough. The “failure” of America’s urban public schools becomes not a consequence of gentrification and urban poverty, but of “bad teachers.” The shuttering of arts and foreign language departments becomes a logical consequence of low enrollments, as if low enrollments don’t occur within the context of a society that views having a variegated set of interests and capabilities as something you do to put on your college application, then abandon ever earlier for unpaid internships and “career opportunities.”

Somehow, educators and institutions of education have taken the brunt of criticism for failing society in so many ways, as if growth-minded universities are more responsible than growth-obsessed American society for producing what Deresiewicz calls “excellent sheep,” uncultivated, one-dimensional souls.

But now it’s time for students and educators who have been defined out of the conversation about America’s future to relish our vantage point as the “useless” detritus of perpetual growth. Instead of defending the humanities, we should be pressuring detractors to justify their Gradgrindian vision of a world that has no time for things like the humanities: a world of unpaid interns, disposable labor, the manufactured conformity of the workplace, and the wearying fear of cultivating any interests and values that don’t obviously or immediately lead to economic growth. Both in training and in perspective, humanities students, scholars and graduates are well positioned to address the ultimate question of value facing American society today: To what extent has a reliance on markets to make (or bypass) determinations of value placed America in crisis on numerous fronts?

Shares