I first heard Bedhead in 1994, when one of my roommates bought "WhatFunLifeWas" after reading a review in Melody Maker. I was in my mid-20s, living in a city where I had moved with the expectation that it would be more urbane and artistic than the suburbs of my youth. Like many in my generation, I was stuck in an adolescent purgatory trying to reconcile the idea of being an “adult” — of paying for my existence — with naive aspirations about making a living in a creative, expressive or ultimately “meaningful” manner. As I played the record, everything I assumed about music generally — and “indie rock” specifically, which is what interested me at the time — was turned on its head.

More than just a collection of songs, the record changed the way I thought about my life. It wasn’t the first to do so; I had worshipped many timeless rock albums — "Zen Arcade" was probably the best example, or "The Queen Is Dead" — that work in similar realms, but something about "WhatFunLifeWas" made me feel like I was hearing music that was a more tenable reflection of my position in the world; it described where I wanted to go. I had not understood the potential of rock music to address issues of life, death, God and faith. Some of this awareness was because I was playing in a band, and some of it was because of my age and the dawning certainty that I needed to grow up.

It was an understanding that made "WhatFunLifeWas" seem almost as daunting as it was inspiring. I recently spoke to several old friends of the band, including Keven McAlester, who now works as a filmmaker and remembered having a similar reaction to the record: “It was astounding that these guys seemed to emerge fully formed at an age when I was still woefully confused about how to do anything well. What I might have guessed, if I knew then what I know now, is that they did not emerge fully formed at all, but had probably spent some or all of every day since they were 10 years old playing and writing and recording music, getting all the bullshit and plagiarism and insecurity and bad ideas out of their system, taking parts of what they liked and what they were good at and refining it until they arrived at something that was their own.”

A little bit of background about the band — and the Kadanes, who wrote the songs — bears out McAlester’s theory: The two brothers (Bubba two years older than Matt) were from Wichita Falls, a small city in Texas about 120 miles northwest of Dallas. I’ve never been to Wichita Falls, but my impression is that it offered a suburban mix of "Dazed and Confused"-slash-"Breakfast Club" conformity/non-conformity infused with an element of whatever it is (desert heat, guns, oil, tornadoes, extremes of political independence, entrepreneurial vision and slackerdom, etc.) that makes Texas a state of mind as much as a state. Matt Kadane recently described Wichita Falls to me as “small and mainstream, open with lots of empty space between buildings. It was not cosmopolitan and therefore a maker of extreme types and people with cosmopolitan ambition.” In part because their father loved playing the drums, the Kadanes grew up with music. Matt took piano lessons and Bubba focused on the guitar. “Ever since Matt and I were teenagers,” Bubba recalled, “all we wanted to do was have a band. We tried everything from a two-man band in my room during junior high school to starting bands with other local kids who could barely hold their instruments.”

They eventually ended up in Dallas, where they began playing with some great musicians like drummer Misch McKay (also from Wichita Falls and, later, of the band Macha) and, as strange as it may sound, violinist Martie Erwin from the Dixie Chicks. During this period, the Kadanes kept writing songs and experimenting with instrumentation. Martie played with them for about a year before, in Bubba’s words, “she left us for the C-and-W big time.” But the violin had opened up some possibilities they weren’t ready to let go of; after Martie left, the Kadanes added a viola.

They found a permanent drummer after Matt met Trini Martinez through a mutual friend. “I first heard Trini play with the Richland Community College lab band,” Matt remembered. “This was a collection of about 30 guys in their 70s, all wearing white suit jackets and playing big band jazz. Trini sat in the middle of the group, reading drum music as he played things like the theme song to 'The Pink Panther.' It all had a Rat Pack feel, and Trini, whose uncle is Trini Lopez, was in his element there as much as in a rock band.”

More permutations of instruments and names ensued. Bubba and Matt spent years reworking songs, breaking them down to their essential elements, searching for the perfect tempo to give the songs space to breathe while keeping enough weight, along with a natural tension and release. But they also started to think that having a viola on every song was too much — “a tacked-on novelty,” in Bubba’s words.

Matt, Bubba and Trini met bassist Kris Wheat and guitarist Tench Coxe around that time and decided to form a new band with the idea that they would use three guitars and Tench would, more or less, assume the role previously played by the viola. By 1991, the lineup was complete.

The band was extraordinarily patient; they spent the better part of two years rehearsing and playing as many shows as possible — in both Fort Worth and Dallas — before they recorded their debut album, "WhatFunLifeWas," in 1993. A key factor was a club in Fort Worth called Mad Hatters, where they met King Coffey, the drummer in the Butthole Surfers and the owner of Trance Syndicate Records. King was from Fort Worth and played drums in the ’80s for a hardcore band called the Hugh Beaumont Experience before joining the Butthole Surfers. With his partner Craig Stewart, he founded Trance in 1990 and focused his attention on Texas acts. The band liked him right away; when he offered to release their records, Matt said, “We never thought about looking for another label. It was important to us at the time to be a part of a Texas label, but one with national reach, and Trance was it.”

The band recorded "WhatFunLifeWas" over the summer of 1993 and released it in April of 1994. When I first heard the album, it struck me as unself-consciously beautiful, completely devoid of the irony that, for better or worse, was prevalent in a lot of rock at the time. Bedhead was composed, lyrical and reflective. Many of the songs featured non-standard meters, and the band wasn’t interested in verse/chorus/bridge/chorus. The record still fell mostly within the parameters of “rock,” not only on account of the instrumentation — guitars, bass and drums — but also because of a judicious use of distortion and feedback. You could still hear traces of possible influences, but they merely provided some of the foundation on which Bedhead’s architecture was built. You also didn’t hear dissonant tunings that were popular on many “post-rock” albums of the time, and the odd meters, when they appeared, never felt forced or self-aggrandizing; Bedhead’s music was about as far removed from a “math rock” circle jerk as a Beethoven sonata.

The band may have traded in faith, but there was never any proselytizing. As the name of the record implies, the songs tackled subjects that were so far off the radar screen of most people I knew that their appearance on a debut album by an underground rock band from Texas seemed prophetic. The minimalist artwork added to the effect — its songs were listed on the front cover, like a table of contents — making the record seem like a manifesto, even before you heard a single note.

“Liferaft” opens the record with what sounds like an improvised guitar line being played in the middle of nowhere. There’s a kind of shy or questioning quality to the guitar that makes it endearing. You want to understand its plight, as if it were a sad, precocious child abandoned by its parents. Or maybe, to think of it another way — and given what we know about the band’s geographical roots — we might imagine a tattered, dead leaf blowing across the Texas desert. It quietly scratches at the friable sand until a gust of wind lifts it up, where it slowly circles in the air. As other guitars are folded into the mix along with a desultory drumbeat, we might picture other leaves pulled into this eddy; and as we do, we begin to understand that what initially seemed like a random act of nature is actually choreographed. If we could freeze this moment — and let’s add a low, gilded light breaking through the clouds across the infinite sky — we find ourselves suddenly moved by its beauty, and already a bit bereft at our inability to explain it in anything more than mundane terms: leaf, desert, sky, wind, sand, light. Or in the case of Bedhead: guitars, bass, drums, voice.

The band subsequently released two EPs, including the "The Dark Ages EP" in February 1996. Though clocking in at just under 15 minutes, the EP feels expansive without a wasted second. By delivering three very stylistically different (but thematically similar) songs, it might also be the perfect introduction to the band if you didn’t want to start at the chronological beginning. This record was followed by the band’s second LP, "Beheaded" — released in June 1996 — which I sometimes joke is the "Empire Strikes Back" of the Bedhead trilogy. The album — which addresses the overwhelming torpor of everyday life — is easily the bleakest of the three, yet it’s also the most hauntingly beautiful, and, for that reason, the most hopeful.

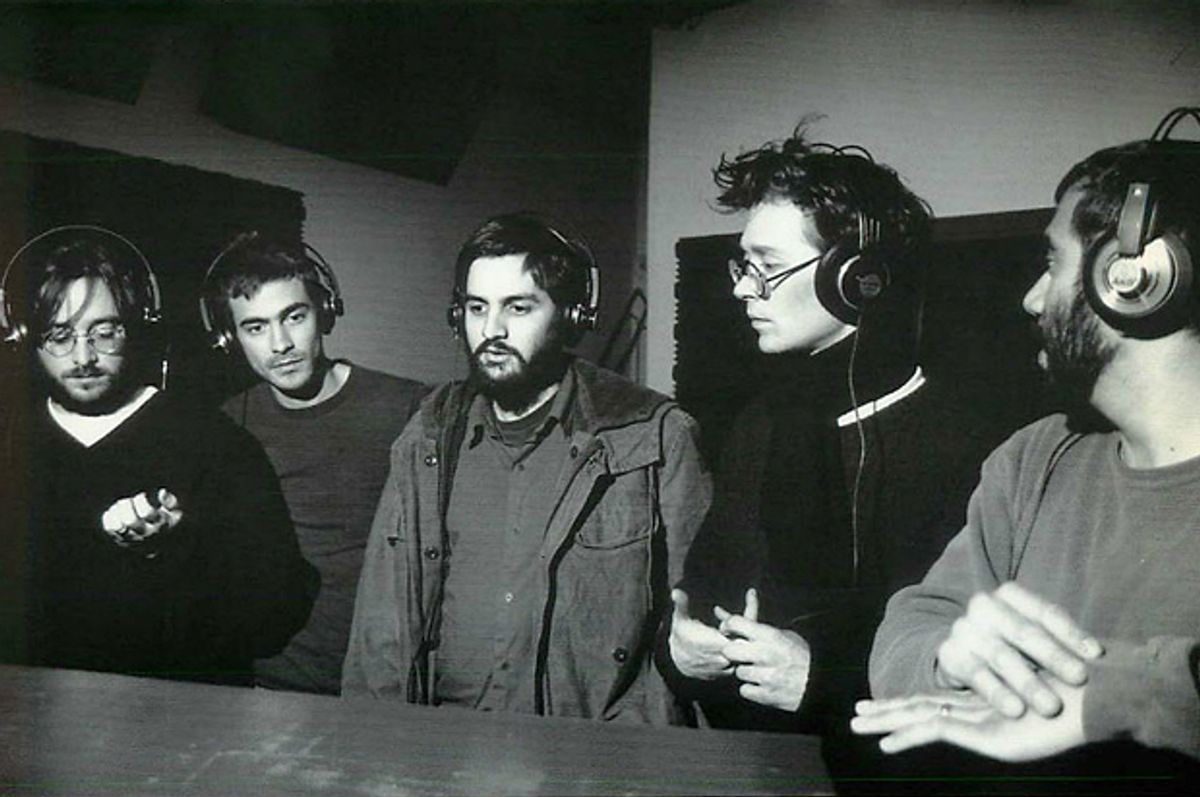

For their third and final LP — "Transaction de Novo" — the band turned to Steve Albini, who engineered the sessions in 10 days. “I met them in full flower,” he remembered, “in the depths of their mania, pursuing contemplative music with the kind of intensity normally found in psychopaths. No detail was too small to sweat, no crack in the veneer not worth gluing and clamping. But it was more than their music. A band provides cover for grown men to maintain the rituals of adolescence without wallowing in them or degrading the rest of their lives.”

Despite being the record the band recorded most quickly, "Transaction de Novo" is the most sonically complex of the Bedhead LPs; there’s a greater range of effects (from very clean to very distorted) and “distance,” the way certain instruments sound as if your head is right next to them, or at other times seem to be coming at you from across a very large hall. Many of the songs have two bass lines. Though still very much “live,” the sound is constantly mutating. Listening to this record, I feel like I’m seeing the band perform on a gigantic turntable, allowing different instruments and parts of songs to ebb and flow in and out of the mix. Some of this complexity can be attributed to the band’s increasing sophistication in the studio, and some to Albini, who summed up the band’s legacy perfectly. “I thought they and their music were brilliant. We built a common language, equal parts philosophy, rock music, and disdain for the dullness around us.”

(This essay was adapted from “Life After Bedhead,” a book of liner notes included with Bedhead 1992-1998, a box set of 5 LPs or 4 CDs containing the complete studio recordings of the band, available from the Numero Group.)

Shares