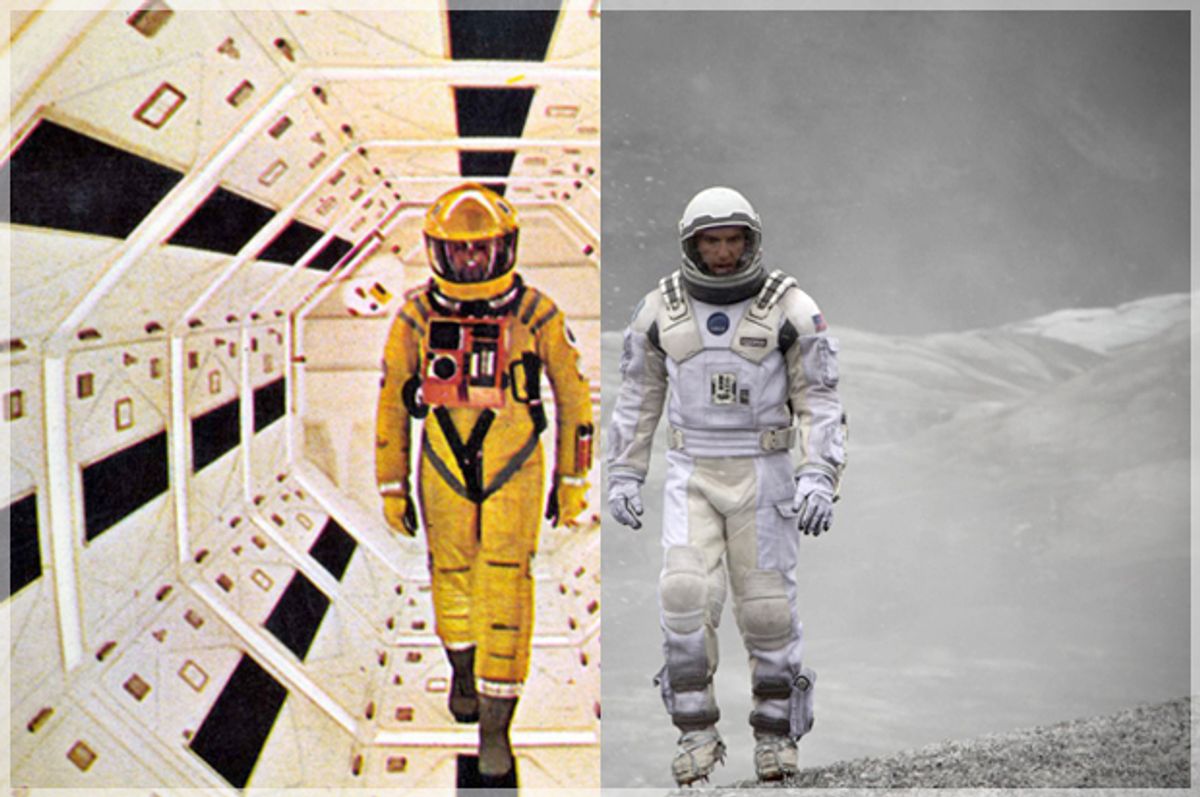

When I first heard about Christopher Nolan’s new sci-fi adventure, "Interstellar," my immediate thought was only this: Here comes the latest filmmaker to take on Stanley Kubrick’s "2001: A Space Odyssey." Though it was released more than 40 years ago, "2001" remains the benchmark for the “serious” science fiction film: technical excellence married to thematic ambition, and a pervading sense of historic self-importance.

More specifically, I imagined that Nolan would join a long line of challengers to aim squarely at "2001’s" famous Star Gate sequence, where astronaut Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) passes through a dazzling space-time light show and winds up at a waystation en route to his transformation from human being into the quasi-divine Star Child.

The Star Gate scene was developed by special effects pioneer Douglas Trumbull, who modernized an old technique known as slit scan photography (you can learn more about it here). While we’ve long since warp-drived our way beyond the sequence effects-wise (you can now do slit scan on your phone), the Star Gate’s eerie and propulsive quality is still powerful, because it functions as much more than just eye candy. It’s a set piece whose theme is the attempt to transcend set pieces — and character, and narrative and, most of all, the technical limitations of cinema itself.

In "2001," the Star Gate scene is followed by another scene that also turns up frequently in sci-fi flicks. Bowman arrives at a series of strange rooms, designed in the style of Louis XVI (as interpreted by an alien intelligence), and he watches himself age and die before being reborn. Where is he? Another galaxy? Another dimension? Heaven? Hell? What are the mysterious monoliths that have brought him here? Why?

Let’s call this the Odd Room Scene. Pristine and uncanny, the odd room is the place at the end of the journey where truths of all sorts, profound and pretentious, clear and obscure, are at last revealed. In "The Matrix Reloaded," for instance, Neo’s Odd Room Scene is his meeting with an insufferable talking suit called the Architect, where he learns the truth about the Matrix. Last summer’s "Snowpiercer," about a train perpetually carrying the sole survivors of a new Ice Age around the world, follows the lower-class occupants of the tail car as they stage a revolution, fighting and hacking their way through first class toward the train’s engine, an Odd Room where our hero learns the truth about the train.

These final scenes in "2001" still linger in the collective creative consciousness as inspiration or as crucible. The Star Gate and the Odd Room, particular manifestations of the journey and the revelation, have become two key architectural building blocks of modern sci-fi films. The lure to imitate and try to top these scenes, either separately or together, is apparently too powerful to resist.

Perhaps the most literal of the Star Gate-Odd Room imitators is Robert Zemeckis’s 1997 "Contact." It’s a straightforward drama about humanity’s efforts to build a large wormhole machine whose plans have been sent by aliens, and the debate over which human should be the first to journey beyond the solar system. The prize falls to Jodie Foster’s agnostic astronomer Ellie Arroway. During the film’s Star Gate sequence, Foster rides a capsule through a wormhole that winds her around distant planets and through a newly forming star. Zemeckis’s knockoff is a decent roller coaster, but nothing more. Arroway is anxious as she goes through the wormhole, but still in control of herself; a deeply distressed Bowman, by contrast, is losing his mind.

Arroway’s wormhole deposits her in an Odd Room that looks to her (and us) like a beach lit by sunlight and moonlight. She is visited by a projection of her dead father, the aliens’ way of appearing to her in a comfortable guise, and she learns the stunning truth about … well, actually, she doesn’t learn much. Her father gives her a Paternal Alien Pep Talk. Yes, there is a lot of life out in the galaxy. No, you can’t hang out with us. No, we’re not going to answer any of your real questions. Just keep working hard down there on planet Earth; you’ll get up here eventually (as long as you all don’t kill each other first).

Brian De Palma tried his own version of the Odd Room at the end of 2000’s "Mission to Mars," which culminates in a team of astronauts entering a cool, Kubrick-like room in an alien spaceship on Mars and, yes, learning the stunning truth about the origins of life on Earth. De Palma is a skilled practitioner of the mainstream Hollywood set piece, but you can feel the film working up quite a sweat trying and failing to answer "2001," and early-century digital effects depicting red Martians are, to be charitable, somewhat dated.

But here comes "Interstellar." This film would appear to be the best shot we’ve had in years to challenge the supremacy of the Star Gate, of "2001" itself, as a Serious Sci-Fi Film About Serious Ideas. Christopher Nolan should be the perfect candidate to out-Star Gate the Star Gate. Kubrick machined his visuals to impossibly tight tolerances. Nolan (along with his screenwriter brother Jonathan) do much the same to their films’ narratives, manufacturing elaborately conceived contraptions. The film follows a Hail Mary pass to find a planet suitable for the human race as the last crops on earth begin to die out. Matthew McConaughey plays an astronaut tasked with piloting a starship through a wormhole, into another galaxy and onto a potentially habitable planet. "Interstellar" promises a straight-ahead technological realism as well as a sense of conscious “We’re pushing the envelope” ambition. (Hey, even Neil deGrasse Tyson vouches for the film’s science bonafides.) The possibilities and ambiguities of time, one of Nolan’s consistent concerns as a storyteller, is meant, I think, to be the trump card that takes "Interstellar" past "2001."

But the film is not about fealty to, or the realistic depiction of, relativity theory. It’s about "2001." And before it can try to usurp the throne, "Interstellar" must first kiss the ring. (And if you haven’t seen "Interstellar" yet, you might want to stop reading now.) So we get the seemingly rational crewmember who proves to be homicidal. The dangerous attempt to manually enter a spaceship. More brazenly, there’s a set piece of one ship docking with another. In "2001," the stately docking of a spaceship with a wheel-shaped space station, turning gently above the Earth to the strains of the Blue Danube was, quite literally, a waltz, a graceful celestial courtship. It clued us in early that the machines in "2001" would prove more lively, more human, than the humans. "Interstellar" assays the same moment, only on steroids. It turns that waltz, so rich in subtext, into a violent, vertiginous fandango as a shuttle tries to dock with a mothership that’s pirouetting out of control.

Finally, after a teasing jaunt through a wormhole earlier in the movie, we come to "Interstellar’s" Star Gate moment, as Cooper plummets into a black hole and ultimately into a library-like Odd Room that M.C. Escher might have fancied. It’s visually impressive for a moment, but its imprint quickly fades.

It’s too bad." Interstellar" wants the stern grandeur of "2001" and the soft-hearted empathy of Steven Spielberg, but in most respects achieves neither. Visually only a few images impress themselves in your brain — Nolan, as is often the case in his movies, is more successful designing and calibrating his story than at creating visuals worthy of his ambition. Yet the film doesn’t manage the emotional dynamics, either. It’s not for lack of trying. The Nolan brothers are rigorous scenarists, and the concept of dual father-daughter bonds being tested and reaffirmed across space-time is strong enough on the drawing board. (Presumably, familial love is sturdier than romantic love, though the film makes a half-hearted stab at the latter.)

For those with a less sentimental bent, the thematic insistence on the primacy of love might seem hokey, but it’s one way the film tries to advance beyond the chilly humanism of Kubrick toward something more warm-blooded. Besides, when measured against the stupefying vastness of the universe, what other human enterprise besides love really matters? The scale of the universe and its utter silence is almost beyond human concern, anyway.

So I don’t fault a film that suggests that it’s love more than space-age alloys and algorithms that can overcome the bounds of space and time. But the big ideas Nolan is playing with are undercut by too much exposition about what they mean. The final scene between Cooper and his elderly daughter — the triumphant, life-affirming emotional home run — is played all wrong, curt and businesslike. It’s a moment Spielberg would have handled with more aplomb; he would have had us teary-eyed, for sure, even those who might feel angry at having their heartstrings yanked so hard. This is more like having a filmmaker give a lecture on how to pull at the heartstrings without actually doing it.

Look, pulling off these Star Gate-like scenes requires an almost impossible balance. The built-in expectations in the structure of the story itself are unwieldy enough, without the association to one of science fiction’s most enduring scenes. You can make the transcendent completely abstract, like poetry, a string of visual and aural sensations, and hope viewers are in the right space to have their minds blown, but you run the risk of copping out with deliberate obfuscation. (We can level this charge at the Star Gate sequence itself.)

But it’s easy to press too far the other way — to personify the higher power or the larger force at the end of these journeys with a too literal explanation that leaves us underwhelmed. I suppose what we yearn for is just a tiny revelation, one that honors our desire for awe, preserves a larger mystery, but is not entirely inaccessible. It’s a tiny taste of the sublime. There’s an imagined pinpoint here where we would dream of transcendence as a paradox, as having God-like perception and yet still remaining human, perhaps only for a moment before crossing into something new. For viewers, though, the Star Gate scenes ultimately play on our side of that crossroads: To be human is to steal a glimpse of the transcendent, to touch it, without transcending.

While Kubrick didn’t have modern digital effects to craft his visuals with, in retrospect he had the easier time of it. It’s increasingly difficult these days to really blow an audience’s minds. We’ve seen too much. We know too much. The legitimate pleasure we can take in knowledge, in our ability to decode an ever-more-complex array of allusions and references, may not be as pleasurable or meaningful as truly seeing something beyond what we think we know.

Maybe the most successful challenger to Kubrick was Darren Aronofsky and his 2006 film "The Fountain." The film, a meditation on mortality and immortality, plays out in three thematically-linked stories: A conquistador (Hugh Jackman) searches the new world for the biblical Tree of Life; a scientist (Jackman again) tries to save his cancer-stricken wife (Rachel Weisz), and a shaven-headed, lotus-sitting traveler (Jackman once more) journeys to a distant nebula. It’s the latter that bears the unique "2001" imprint of journey and revelation: Jackman travels in a bubble containing the Tree of Life, through a milky and golden cosmicscape en route to his death and rebirth. It’s the Star Gate and the Odd Room all in one. Visually, Aronofsky eschewed computer-generated effects for a more organic approach that leans on fluid dynamics. I won’t tell you the film is a masterpiece — its Grand Unifying ending is more than a little inscrutable; again, pulling this stuff of is a real tightrope — but the visuals are wondrous and unsettling, perhaps the closest realization since the original of what the Star Gate sequence is designed to evoke.

Having said that, though, it may be time to turn away from the Star Gate in our quest for the mind-blowing sci-fi cinematic sequence. Filmmakers have thus far tried to imagine something like it, only better, and have mostly failed. It’s harder to imagine something beyond it, something unimaginable. Maybe future films should not be quite so literal in their chasing of those transcendent moments. This might challenge a new generation of filmmakers while also allowing the Star Gate, and "2001" itself, to lie fallow for awhile, so we can return to it one day with fresh eyes.

It is, after all, when we least suspect it that a story may find a way past our jaded eyes and show us a glimpse of something that really does stir a moment of profound connection. There is one achingly brief moment in "Interstellar" that accomplishes this: Nolan composes a magnificent shot of a small starship, seen from a great distance gliding past Saturn’s awesome rings. The ship glitters in a gentle rhythm as it catches light of the Sun. It’s a throwaway, a transitional moment between one scene and another, merely meant to establish where we are. But its very simplicity and beauty, the power of its scale, invites us for a moment to experience the scale of the unknown and to appreciate our efforts to find a place in it, or beyond it.

Shares