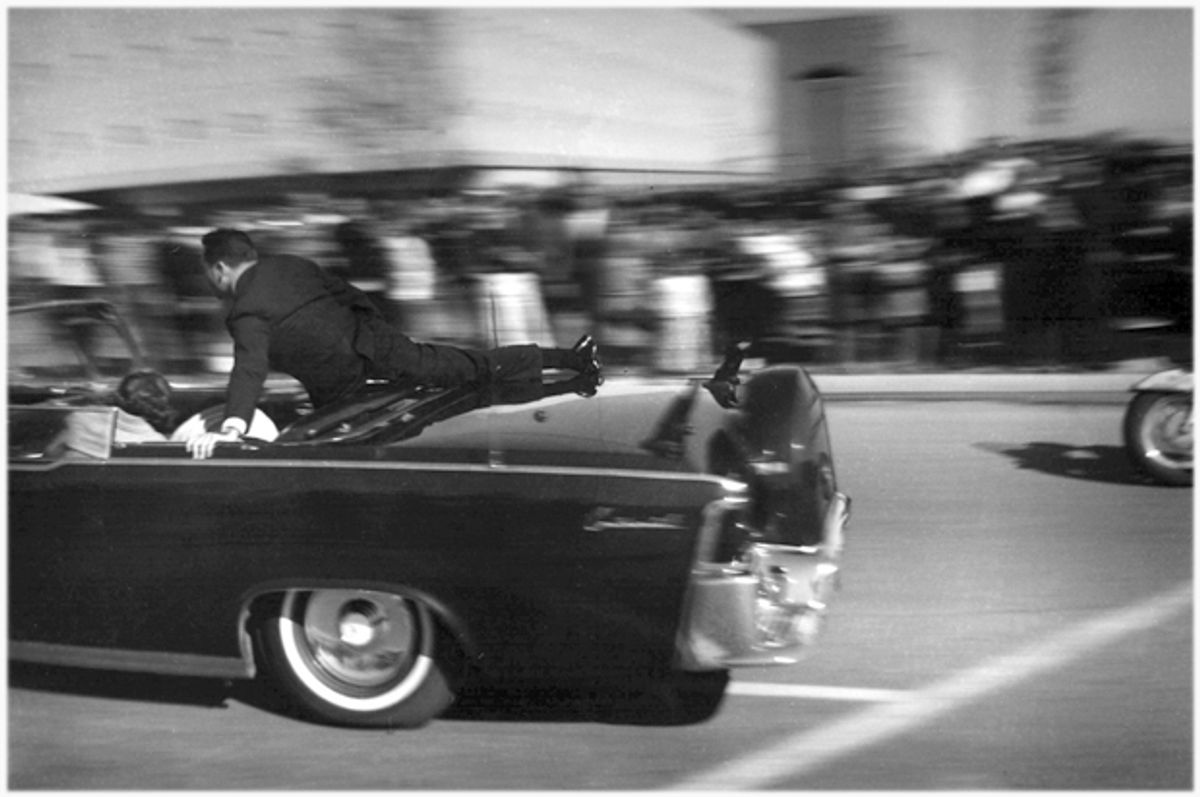

Every year, without fail, the president dies all over again. For a few days every autumn, the entire media is overwhelmed by those haunting photos from Dallas. Those cruelly happy and innocent pictures of a young president smiling and waving at bystanders, the first lady clutching a bouquet of roses. With their soft, prelapsarian colors, they seem to hail from another universe—one that has been stolen from us.

Perhaps it is that feeling of loss that explains the lingering sense of grief over John F. Kennedy’s assassination year after year, when the anniversaries of other, equally shocking events—from Pearl Harbor to 9/11—are generally quieter affairs. But there is also something unfinished about Kennedy’s death, a lingering suspicion that no one has ever been able to banish.

For the public has never embraced the official verdict, handed down by the Warren Commission in September 1964. After less than a year of hearings and deliberations, the team—led by Chief Justice Earl Warren—concluded that President Kennedy had been shot and killed by Lee Harvey Oswald, a 24-year-old ex-Marine portrayed by the Commission as a shiftless loner with communist sympathies. But they could not explain why.

The most obvious question about the murder was also the one that could not be answered. Not only had Oswald been murdered in police custody two days after the assassination, but the Commission had been unable to find a single person who remembered Oswald criticizing Kennedy. On the contrary, Oswald had frequently expressed his admiration for the president. The Commission interviewed at least six witnesses who remembered Oswald praising Kennedy.

Faced with a substantial hole in their case, the Commission tried to plug it by filling the report with airy speculation about Oswald’s tormented psyche. Oswald, they insisted, was someone who had been driven by “resentment of all authority,” “antagonism toward the United States” and an “urge to try to find a place in history.” Perhaps he had shot the president, the Report blandly suggested, because of his “inability to enter into meaningful relationships with people.”

But this conclusion was not reached in a vacuum. From the moment it was established, the Warren Commission was under tremendous pressure to calm a hysterical public and quash the widespread rumors of a conspiracy that exploded across the country in the days following the public killing of the president’s accused assassin. As Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach put it in a memo written hours after Oswald’s death, “We need something to head off public speculation or Congressional hearings of the wrong sort.”

That “speculation” never went away. In 1966, the first national poll taken on the subject found that 46 percent of Americans believed that JFK had been struck down by a plot. Last year, a Washington Post-ABC News poll found that 62 percent of the public rejected the idea that a single man had killed the president.

The Post reported this development with a palpable sense of bafflement, for the mainstream media has always treated skeptics of the official account with impatience, even scorn. For them, the Kennedy case was cracked and closed long ago. Last year, Jill Abramson blithely informed readers of The New York Times that “the historical consensus seems to have settled on Lee Harvey Oswald as the lone assassin,” dismissing the wealth of information about the assassination that can be found online as “unfiltered and at times unhinged musings.”

As far as the vast majority of the American press is concerned, critics of the Warren Commission are in a class with the paranoids who doubt that the moon landing occurred, that President Obama was born in the United States, or that al Qaeda was responsible for the 2001 terrorist attacks. They insist, as Adam Gopnik did in a meandering New Yorker essay last year, “that the evidence that the American security services gathered, within the first hours and weeks and months, to persuade the world of the sole guilt of Lee Harvey Oswald remains formidable,” and that anyone who differs with this assessment is an “obsessive” or a “buff” with no life. Some defenders of the Warren verdict sound as passionate as any conspiracy theorists: Chris Matthews, an admirer of Kennedy, once told his audience that assassination skeptics cling to conspiracy theories “because they cannot bear the suffering that truth brings to the heart and to the mind.”

It can be shocking, after reading such dismissive remarks, to learn that some of the most powerful people in the United States expressed skepticism about the official account of JFK’s death. John Kerry might have startled some people when he admitted last year that he entertained “serious doubts” about the Warren verdict, but he was far from the first member of the political establishment to say so.

President Lyndon Johnson, who commissioned the Warren Report, was never satisfied by its conclusions. “I can’t honestly say that I’ve ever been completely relieved of the fact that there might have been international connections,” he told Walter Cronkite in 1969, adding that Oswald was “a mysterious fellow” whose motivations remained uncertain. “I never believed that Oswald acted alone, although I can accept that he pulled the trigger,” he told another journalist in 1971. Senator Richard Russell, a member of the Warren Commission, disagreed with the final report, particularly the controversial claim that JFK and Texas Governor John Connally had been struck by the same bullet—a conclusion that Connally himself doubted.

While the Kennedy family has been guarded in its public statements on the subject, they privately expressed doubts that Oswald had acted alone. A week after the assassination, Robert and Jacqueline Kennedy sent a back-channel message to Soviet leaders, telling them that they believed that “the president was felled by domestic opponents.” In 2013, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. revealed that his father had dismissed the Warren Report as “a shoddy piece of craftsmanship.”

Other Washington bigwigs have given voice to similar suspicions. In his memoirs, former House Speaker Tip O’Neill recalled that JFK aides Kenneth O’Donnell and Dave Powers—both of whom had been riding in JFK’s motorcade at the moment of the assassination—once told him that they had heard two shots coming from the grassy knoll, across the street from where Oswald is alleged to have fired all of the shots. CIA Director John McCone told RFK that he believed two gunmen had been present in Dealey Plaza. In 1992, both Al Gore and Bill Clinton expressed guarded doubts that Oswald had acted alone.

In short, even as the media strained to portray the Warren Commission’s verdict as unassailable, some of the most powerful figures in Washington, past and present, publicly and privately admitted that they found it hard to swallow. None of these people were flakes, none were easily fooled, and none could be considered “obsessives” or “buffs.” Why did they feel, instinctively, that something was wrong in the Kennedy case?

The answer lies not in the much-debated minutiae of the case—in how many shots were fired, the order in which the wounds were inflicted, and the reliability of each witness. The real mystery lies not in the facts that are disputed, but in the facts that are known. There is something profoundly strange about the story of Lee Harvey Oswald as it was presented by the Warren Commission.

In 1956, at the age of 17, Oswald quit high school to join the U.S. Marine Corps. He was no ordinary Marine: From 1957 through 1958, he was assigned to work as a radar operator at Atsugi Naval Air Base in Japan. Atsugi was not only a major CIA station, but also the home base of the top-secret U-2 spy plane, used to conduct reconnaissance missions inside the Soviet Union. While working at Atsugi, Oswald—as his commanding officer told the Warren Commission—“had access to the location of all bases in the West Coast area, all radio frequencies for all squadrons, all tactical call signs, and the relative strength of all squadrons.”

In 1959, Oswald abruptly quit the marines and traveled to Russia, where he declared his intention to defect to the Soviet Union. He subsequently turned up at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, where he dramatically announced that he intended to spill all of the secrets he had learned as a marine to his new country’s government. He even bragged that he “might know something of special interest” to the Soviets.

This should have set off alarm bells in every corner of the U.S. intelligence community. Defections to the Soviet Union were rare enough; a former marine who had access to top-secret, highly sensitive information was something else again. When the U-2 plane was shot down by Soviet guns in May 1960, Oswald might well have been considered the most likely culprit. The young defector should have been poised to be condemned as the Edward Snowden of his day.

But he was not. The vast U.S. national-security establishment showed virtually no interest in Oswald. When Oswald decided to return home in 1962—two years after openly declaring his intent to betray his country to its deadliest enemy—he received a warm welcome. He faced no investigation and had no trouble obtaining a new passport; the U.S. State Department even lent him $435 for his traveling expenses. Upon returning home, Oswald began noisily campaigning in support of Communist Cuba, again without attracting the attention of the intelligence community.

Why was Oswald treated so lightly? As Sylvia Meagher put it in “Accessories After the Fact,” her groundbreaking 1967 critique of the Warren Report: “There is a consistent pattern of unusual and favorable treatment of Oswald by the State Department. Decision after decision, the Department removed every obstacle before Oswald—a defector and would-be expatriate, self-declared enemy of his native country, self-proclaimed discloser of classified military information, and later self-appointed propagandist for Fidel Castro—on his path from Minsk to Dallas.”

At the height of the Cold War, when tensions with the Soviet Union were at an all-time high, this professed traitor was apparently not even debriefed by the CIA upon his return to the U.S. In 1975, the CIA’s then-director William Colby insisted that the CIA had never had any contact at all with Oswald, either before or after his defection.

This conspicuous silence is the black hole at the heart of the JFK assassination, a mystery that cannot easily be explained away. There seems to be no rational reason why a prominent defector and outspoken quisling should have been so blithely overlooked by the entire national security establishment, in an era when hysteria over potential Soviet infiltration was so fierce that Hollywood celebrities, civil rights activists and union organizers were all being targeted for their alleged communist connections. It is no accident that the report could not establish a coherent motive for Oswald; the very facts of Oswald’s life seem incoherent. Something is missing.

There is one explanation that seems frighteningly plausible. In his 1990 book “Spy Saga,” Philip Melanson speculated that Oswald may have been recruited by the U.S. government as a low-level intelligence agent, and that his sojourn in Russia was an undercover mission. The evidence is entirely circumstantial, but former CIA Director Allen Dulles himself pointed out to the Warren Commission that there was no paper trail for many of his agency’s men and that many agents would refuse to admit their identity even under oath.

As unlikely as it may sound, this theory would explain why Oswald was not targeted by U.S. intelligence after his defection, and it would explain why he had no trouble returning home. It might also help to explain another Oswald mystery: why an alleged Marxist appears to have had no Marxist friends, spending the majority of his time in the U.S. socializing with right-wing Russian exiles and anti-Castro Cubans—many of whom apparently had CIA connections of their own.

It might explain why Oswald, portrayed by the Warren Report as a fame-seeker who had “sought for himself a place in history,” denied to his last breath that he had killed the president. After Oswald was shot by Jack Ruby on Nov. 24, Detective B. H. Combest asked the dying Oswald if there was anything more he wanted to say. “He shook his head,” Combest recalled. The Warren Commission heard this testimony but chose to omit it from its final report.

It may also explain why the CIA, to this day, refuses to release more than a thousand documents relating to the JFK assassination for reasons of “national security,” a claim that makes no sense if the president was killed by a crank for no reason. For if Oswald was any kind of intelligence agent, the official explanation—relying as it does on the assumption that Oswald was a disgruntled loner—is irreparably shattered, and every single piece of evidence needs to be examined in a new light.

It is highly implausible that the full truth behind John F. Kennedy’s assassination lies buried in those unreleased documents. It is more likely that they contain clues that would further weaken the official account, perhaps to the point where many Americans would feel that their instinctive skepticism was justified enough to demand a new investigation into the matter. Fifty years is a long time to wait for a satisfactory answer; we should have not to wait for fifty more.

We cannot tell where that investigation might lead, or how it might change our understanding of the most famous murder case of the last century. But there is only one way to find out.

Shares