Happy Imperial Royal Amnesty day, everyone! After a great long wait, President Obama finally announced his plan last week to grant Total Amnesty to every undocumented immigrant, forever. (That, or delay the threat of deportation for a couple of years to certain classes of undocumented immigrants.) He also said he would give free cars and cellphones to all undocumented immigrants and seize all private property owned by Republican voters and nationalize of the means of production. Say whaaa? What's he smoking??

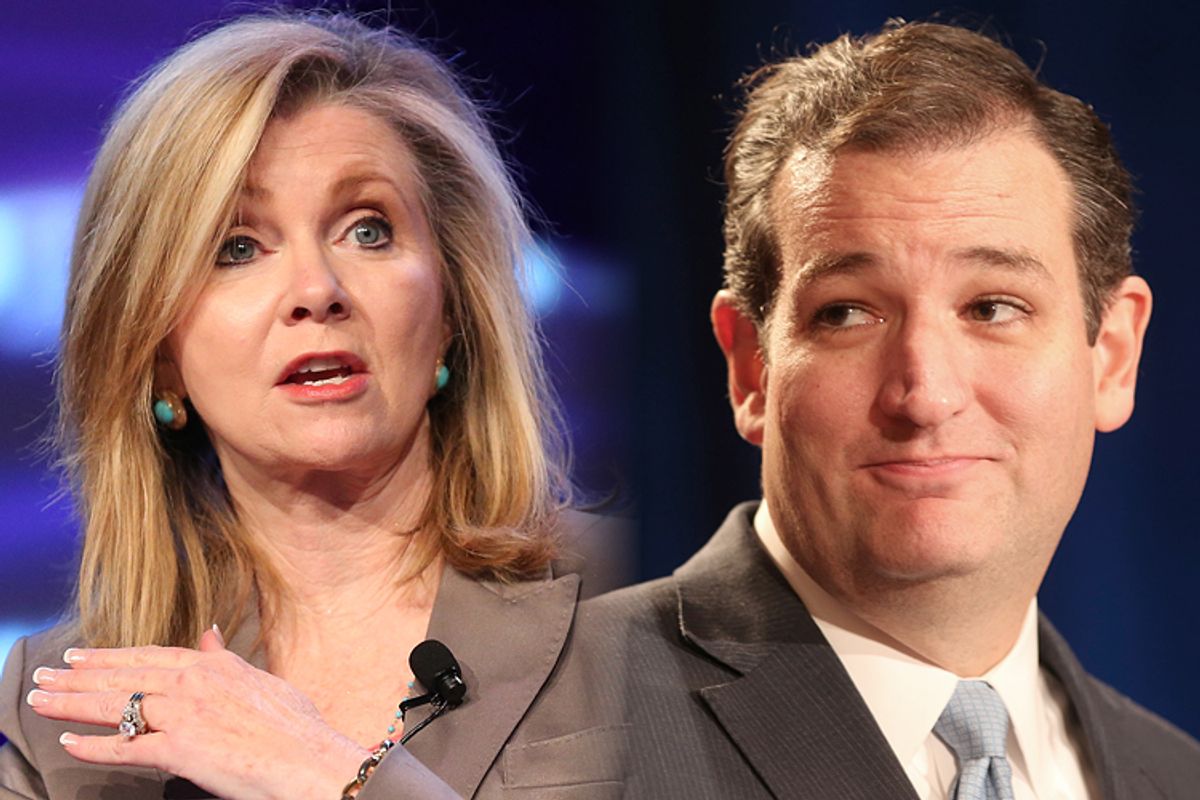

No but really. No matter whether Obama's plan gives one undocumented immigrant or 5 million undocumented immigrants the opportunity to apply for temporary deportation relief, those most viciously opposed to it have been gleefully happy to dub the action "amnesty." Each opponent can personalize the word to his or her suiting through the use of colorful adjectives. Sen. Ted Cruz's recent column, directing the Republican Party to throw its fit over executive and judicial nominations, mentions "amnesty" nine times, including such permutations as "executive amnesty" and "illegal amnesty." (The action is indeed "executive"; the courts have not weighed in on its legality.) Conservative voter fraud guru Hans von Spakovsky describes it as "unilateral amnesty." "Amnesty" is a plain hamburger, with choice toppings available at the Fixin's Bar.

During recent legislative debates over comprehensive immigration reform, in 2006-07 and 2013-14, "amnesty" began at a certain threshold: a path to citizenship, or some other permanent legal status, for those living in the country illegally. Even this was a stretch of the word: Residing unlawfully in the United States is a civil offense that merits a civil remedy. The most common civil remedy is deportation to country of origin. In the Gang of Eight bill that passed the Senate in 2013, the (fairly arduous) path to citizenship that was offered still imposed civil remedies in the form of fines. So it wasn't unconditional. On the other hand, "amnesties" can be conditional. One program that most agree was "amnesty" was the one Gerald Ford offered to Vietnam-era draft dodgers: amnesty in exchange for a period working in some form of civil service. (Eventually Jimmy Carter just started giving out pardons.)

What President Obama announced in his prime-time address Thursday was not a path to citizenship or permanent legal status. Even the Royal Imperial Darth Vader Tyrant President understands that that is not within his power. It will merely defer deportations for, say, those who have family here and haven't committed any crimes. But the term "amnesty" will still be applied by the program's critics, and they'll be able to get away with that because, hey, freedom of speech.

Slate's Betsy Woodruff tried to nail down Republican lawmakers on the threshold for "amnesty." She got mixed results, indicating that "amnesty" may simply be a political term devoid of any concrete meaning. Sen. John Boozman, for example, gives several answers:

I then asked Arkansas’ Sen. John Boozman what he meant when he used the A-word.

“It’s behavior that you don’t want to reward,” he said. “And so if somebody enters the country illegally and then is given the ability to move to the front of the line, as opposed to somebody who goes through the normal process, then I would call that amnesty.”

“It would be a pathway to citizenship,” he said.

According to that definition, the president’s executive action on immigration is not amnesty.

“The sticking point would be in the details,” Boozman added. “That might require whatever.”

Indeed.

Sen. Deb Fischer says, "I don't know!" and laughs when asked whether Obama's executive actions would amount to amnesty. Sen. Johnny Isakson refers to the dictionary definition of amnesty as "forgiveness." This answer offers no insight into its meaning in a political context, but it does suggest that Johnny Isakson views "forgiveness" in a pejorative light.

Others, like Boozman, dodge the question by saying they'll have to wait to see the details to determine whether it constitutes "amnesty." This sudden and convenient enthusiasm for sober-minded assessment is an amusing turn. Thus far they haven't needed to see the details to determine that they don't like it.

Going forward, there's not going to be much point to telling Republicans they're wrong to use "amnesty" in the context of this executive action, even if they're using it more trigger-happily than they might have previously. There's some subjectivity to it. But now that the bar's been set this low, there's little chance of it ever reverting to someplace higher. Woodruff defines the low bar as "bad immigration policy." We'd say that "amnesty," in conservative circles, now refers to an ICE policy of anything less than maximal deportations -- no temporary legal status, no deferments, no discretion or prioritization, no nothing beyond, as the term of art would have it, "roundin' 'em up and throwin' 'em all back over the fence."

The Republican Party position on immigration reform is to pursue a piecemeal approach: first secure the border, and then "deal" with what to do about those 11 million undocumented immigrants already here. In reality this means that Republicans first want a bill to secure the border and then plan to do nothing -- which is why Democrats, after all, insist on a comprehensive approach. Let's imagine for a second, though, that border security legislation is passed and satisfactorily low levels of illegal border crossings measured. Republicans then sit down to draft a bill for that second part. What do they write? Their "amnesty" rhetoric will have left them with no wiggle room to write anything that wouldn't piss off their voting base. But again, they can deal with that, uhh, later.

Shares