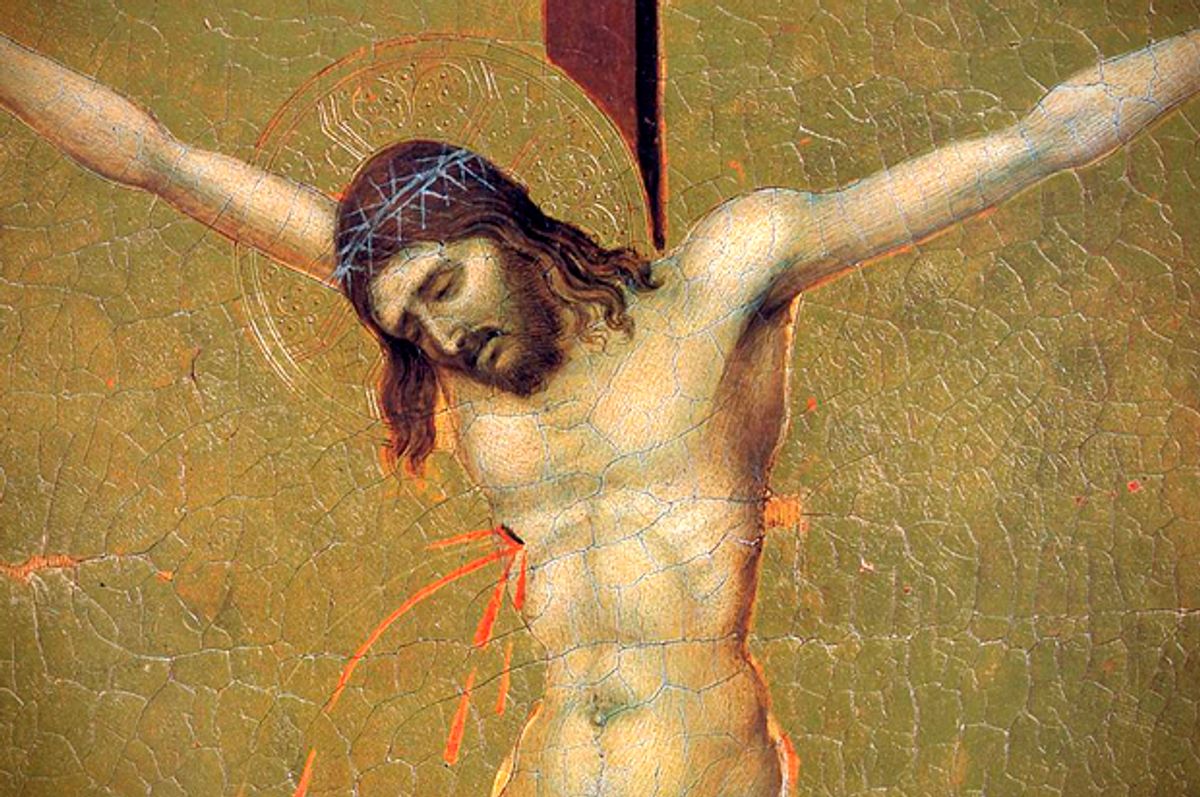

It was a spectacular late summer morning in New York City. I was at a Sunday worship service at Broadway Presbyterian Church, September 16, 2001, five days after the September 11 attack. The whole country was in shock, but in New York we did not just see images of the catastrophe, we could smell it. The ruins of the World Trade Center continued to smolder for days. Flowers were laid at every firehouse, and posters were posted on lampposts asking after missing loved ones. The pastor, Walter Tennyson, pointed to a saying across the back of the sanctuary that read, “We preach Christ and him crucified.” “The Romans used crucifixion as a way to terrorize those they ruled,” he said. “They tried to do that with Jesus, but he was resurrected. The cross, Christ crucified, is our faith’s symbol of facing and living beyond terror.”

I had seen crosses for years: on churches, necklaces, stationary, highways, but I gained a new understanding of the cross that week of September 11 in New York City. For many the cross is a symbol of Christian faith, of piety or religion in general. For me it became a sign of trauma, but not just that: of trauma faced by God alongside us. The cross, a symbol formed in the midst of early Christian trauma, was used effectively by Walter Tennyson to minister to a traumatized Presbyterian community in New York in the wake of 9/11. His sermon invited his church to see Jesus Christ, crucified by the Romans, as the symbol of a traumatized God, a god who was right there with them as they faced and lived beyond their own trauma.

It is important to get clear on what ancient crucifixion was. The word “crucifixion” comes from the Latin word cruciare— “torture.” The Roman Cicero describes it as suma supplicum, “the most extreme form of punishment,” and goes on to say: “To bind a Roman citizen is a crime, to flog him an abomination, to slay him is almost an act of murder, to crucify him is—what? There is not a fitting word that can possibly describe so horrible a deed.” The Jewish historian Josephus describes it as “the most pitiable of deaths.” The victim was first brutally whipped or otherwise tortured. Then his arms were attached to a crosspiece of wood, usually by nails, sometimes by rope. Finally, the victim was hoisted by way of the crosspiece (crux in Latin) onto a pole, and the crosspiece was attached to the pole so that his feet did not touch the ground. There the victim was left on public display until he died. Sometimes death came quickly through suffocation or thirst, but sometimes death was postponed by giving the victim drink. After the victim was dead, the Romans often left the body on the cross as a public display, rotting and eaten by birds. The point was not just to hurt and kill a person but to utterly humiliate a rebel or upstart slave, while terrorizing anyone who looked up to them. Crucifixion was empire-imposed trauma intended to shatter anyone and any movement that opposed Rome.

The Earliest Preserved Story of Jesus' Crucifixion

The impact of the crucifixion can be felt palpably in the earliest narrative about the crucifixion of Jesus found in the New Testament. This narrative is preserved particularly in chapters 14 through 16 of the book of Mark, the earliest gospel in the New Testament.

The exact contents of this early crucifixion narrative are unknown, but it seems that a form of the story of Jesus’ death was known by the authors of the gospels of Mark and John. These two gospels overlap in how they tell of Jesus’ death and rarely elsewhere. In addition, these final chapters in Mark stand out from the rest of the gospel in their style and depiction of Jesus. As a result, most scholars agree that parts of Mark 14–16 are an early crucifixion narrative used by Mark’s author, though they disagree on whether one can determine its exact contents.

These final chapters of Mark present a bleak picture of Jesus’ final days. The story opens in Mark 14 with the decision by “the chief priests and the scribes” to secretly arrest Jesus and kill him before the Passover for fear of starting a riot among the people. Soon thereafter Jesus has a final meal with his disciples at which he predicts that he will be betrayed by one of them, that all of them will desert him, and that Peter, the head disciple, will repeatedly deny to others any association with Jesus. Jesus goes to the garden of Gethsemane to pray to be allowed to avoid death, and his chief disciples fall asleep while waiting for him. Judas then arrives with an armed contingent to arrest Jesus, and Jesus is taken away to be interrogated by the priests of the Jerusalem Temple. While they are interrogating Jesus inside the Temple, his apostle Peter outside denies association with him three times, just as Jesus had predicted. At the outset of Mark 15 the Jewish authorities turn Jesus over to the Roman governor, Pilate, for interrogation and execution. Pilate asks Jesus, “Are you the king of the Jews?” To which Jesus replies, “So you say.” Otherwise, Jesus refuses to respond to any of Pilate’s questions, just as he had been silent before the Temple priests. Pilate speaks to the Jewish crowds and offers to free Jesus, since (the narrative says) it was the custom for the Roman governor to free a Jewish prisoner at Passover. But the crowd loudly proclaims their preference that Barrabas, an anti-Roman insurgent, be freed instead.

From here the crucifixion narrative describes step by step the torture, mocking, and execution of Jesus. Jesus is flogged. Then Roman soldiers dress him up as “the king of the Jews,” strip him, taunt him, and divide his clothes. Finally, they take Jesus to Golgotha, “the place of the skull,” and crucify him between two criminals, who mock him too. Around noon the soldiers offer the dying Jesus sour wine to drink, and he soon dies, crying out in his native Aramaic tongue, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Hung on the cross, Jesus has been abandoned by all who know him except for three women watching from a distance, among them Mary of Magdala and another Mary identified here in Mark as the mother of “the younger James and Joses.” Jesus is hurriedly buried just before the Sabbath. Then, in a section that may or may not have been part of the early crucifixion narrative, three women come after the Sabbath to anoint his body, but they find the tomb empty, and a young man instructs them to tell the disciples that Jesus has risen from the dead. The narrative (and the Gospel of Mark) closes with the women running away “in terror, telling no one anything because of their fear” (Mark 16:8).

This crucifixion narrative reveals the rawness of early responses to Jesus’ death. The Jesus remembered here is no hero offering eloquent speeches and welcoming torture and death. Instead, he prays to God to avoid death and is silent or evasive when questioned. This narrative blames the Jewish leadership first and foremost for Jesus’ death, while the Roman governor, Pilate, comes off as an indecisive and unwilling participant in the process. Yet Jesus’ closest disciples also come off poorly, betraying, denying, and abandoning Jesus in his death. Even the female followers of Jesus who watch his final passing do so from a distance. Formed by the first generation(s) of Jesus’ followers, perhaps this crucifixion story of Jesus’ abandonment preserves tinges of self-blame. These followers, so the story goes, survived by deserting and denying Jesus, while he suffered a humiliating and solitary death. Be that as it may, the story enjoyed a circulation far beyond Jesus’ first disciples, becoming the basis for all four of the New Testament gospel accounts of Jesus’ death.

We do not know when this crucifixion narrative was written, but it is about as close as we can come, I believe, to seeing the early impact that Jesus’ death had on his followers. It was not just that Jesus did not match up to some messianic expectations laid on him. In crucifying Jesus the Romans used a time-tested strategy to obliterate movements they deemed dangerous, devastating his followers.

Now, thousands of years later, with Christianity a worldwide movement, it is easy to overlook the fact that this Roman attempt to obliterate the Jesus movement was almost successful. One of Paul’s early letters, the first one to the Corinthians, acknowledges decades after the fact that “the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing” (1 Corinthians 1:18) and “a stumbling block to Jews, folly to gentiles” (1:23). Even a couple of centuries later we find a prominent critic of the church, Celsus, mocking Christians for following a figure, Jesus, who was “punished to his utter disgrace.” For many in the Greco-Roman world, there was not much more to say about a movement that had its leader, a demonstrable failure, crucified. End of story.

Resistant to Roman Imperial Terrorism Among Early Jesus Followers

But it was not the end of the story. The Messianist community centered on Jesus reinterpreted the crucifixion in ways unanticipated by the Romans. Jesus’ crucifixion became the founding event of the movement and not its end. The move was so radical that many Christians now wear symbols of the cross as a mark of their membership in the movement. The cross is no sign of humiliating defeat for Christians. Instead, it is a proud symbol of movement membership. Jesus’ followers did not end up fleeing from the reality of his crucifixion, but “took up the cross” themselves. Such a thing would have been incomprehensible to Romans. It is an excellent example of the adaptability of symbols, especially in cases like imperial domination, where a dominated group confronts symbolic actions imposed on it by its oppressor. The Roman symbol of ultimate defeat became the Christian symbol of ultimate victory.

How did the first generation of Jesus’ followers accomplish this reinterpretation of crucifixion?

Answering this question is no easy task, since even the above-discussed “crucifixion narrative” probably was written years after Jesus’ death. Yet we have another resource available for uncovering early responses to Jesus’ crucifixion: the traditions of Jesus’ followers preserved in the letters of the New Testament. These letters sometimes date from earlier periods, especially the letters most clearly written by Paul (Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, and Philemon). Through uncovering early traditions known by Paul and other early Jesus followers, we may gain clues to how the early church first responded to Jesus’ death and reinterpreted it. These traditions about the crucifixion may date only years or even mere months after Jesus’ death.

Jesus As The Suffering Servant Of The Hebrew Bible

I start with a quotation of early tradition about Jesus found in Paul’s first letter to the church at Corinth, which he had founded. Writing about 53 or 54 ce, about twenty years after Jesus’ death, Paul says in chapter 15 of that letter:

For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures. (1 Corinthians 15:3–4)

Paul’s reference to “what I in turn received” indicates that he is reciting here an earlier teaching, one Paul himself was told in the founding years of the church. And this brief teaching tells us at least two important things up front. Both assertions, that “Christ died for our sins” and that “he was buried and then raised on the third day” are according to the (Hebrew) scriptures.

This indicates the importance for early followers of Jesus of interpreting Jesus’ death and resurrection through the lens of scripture. These early followers of Jesus, like Jesus himself, were Jewish. Being Jewish, they drew on the Hebrew Bible to make sense of their lives. They readily identified themselves and figures like Jesus with the major actors of the Bible, and they could invoke a given text from the Torah and Prophets through mentioning just some key phrases or a mere rare word found in the given text.

In addition, the first-generation Jesus community did not choose just any Hebrew scripture to understand Jesus’ crucifixion. Rather, in the wake of Jesus’ crucifixion, early Jesus followers found themselves focusing on Hebrew scriptures formed in the midst of earlier Jewish traumas. The scripture best corresponding to the assertion that “Christ was raised on the third day according to the scriptures” comes from the book of Hosea, formed amidst Assyrian trauma. In it, his people look forward to being resurrected as a community—“In two days God will make us whole again, on the third day God will raise us up” (Hosea 6:2). Apparently Jesus’ followers found comfort in this text, finding in it a promise of their community’s revival in the wake of his death. This idea of communal survival after Jesus’ death will be important shortly.

But let us turn to Paul’s other statement that “Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures.” This quote is reminiscent of the suffering servant song in Isaiah 53 formed amidst Babylonian trauma. Recall its repeated focus on the servant’s bearing of the community’s sin—“ours were the sins that he bore; our pains he endured” (verse 4); “he was wounded for our crimes, crushed because of our bloodguilt”(5); “Yahweh allowed the bloodguilt belonging to all of us to harm him” (6). The tradition quoted by Paul looks back on this song, asserting that Jesus’ death on the cross for “our sins” was analogous to the exilic servant’s suffering for the sins of his community. In this sense, Jesus “died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures” and was a “suffering servant.”

Some other early Christian sayings are yet more explicit in seeing Jesus as a suffering servant. For example, the author of the late-first-century letter of 1 Peter says that “Christ suffered for you” and then quotes an early hymn that describes Jesus’ death in terms that repeatedly echo the suffering servant song in Isaiah:

Many Christians assume from texts like this that the suffering servant song in Isaiah 53 accurately prophesied Jesus’ death. Yet it is far more likely that ancient hymns like the one in 1 Peter represent an attempt by Jesus’ followers to retell his story so that it matched and could be interpreted in terms of Isaiah 53. In and of itself, Jesus’ execution at the hands of Romans featured few parallels to the suffering servant seen in Isaiah 53. He died unjustly. But early traditions like the hymn in 1 Peter discussed here connected Jesus’ brutal and apparently senseless death to the poem in Isaiah 53, arguing that Jesus’ death—like the suffering servant’s— made a positive difference for the community that survived him. Jesus died on his people’s account, so that they could, as 1 Peter says, “be healed” and “live for righteousness.”

Through singing this hymn, early Jesus Jews make themselves the “we” seen in Isaiah 53, the “us” whose sins were borne by Jesus, and the “many” made righteous by his pain. Thanks to this redescription and reinterpretation of his death, they behold not just the Roman humiliation but the suffering and vindication of Jesus. They see how his suffering on the cross benefited them.

This link of the suffering servant song to the death of a contemporary figure Jesus was unprecedented. Earlier Jewish texts do not depict Jewish heroes, like those who died resisting Antiochus IV in the Hellenistic crisis, as suffering servants. And Jews before Jesus did not read Isaiah 53 as a prediction of a suffering Messiah. Instead, the closest contemporary analogy to the idea that “Christ died for our sins” was the widespread idea in Greco-Roman culture of heroic figures dying “for” others—their family, friends, or their community. These Greco-Roman ideas probably helped Jesus’ followers understand the significance of his death as well.

Nevertheless, both the brief pre-Pauline teaching that “Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures” and the longer hymn in 1 Peter add an element of communal guilt to the story of Jesus’ noble death. If we look for a precursor to that element, we find it repeatedly in Isaiah 53 (“our sins,” “our pains,” “our crimes,” “our bloodguilt”) but not in the Greco-Roman parallels. To be sure, the early followers of Jesus probably saw him as another hero who had “died for” others. But they seem to have seen Jesus as a particular type of such a hero, one modeled on the suffering servant of Isaiah 53.

Excerpted from "Holy Resilience: The Bible’s Traumatic Origins," by David M. Carr, published by Yale University Press in November 2014. Reproduced by permission.

Shares