When students come to John Figdor, the humanist chaplain at Stanford, they’re often comfortable with their atheism. Big questions about God aren’t necessarily on their minds. Big questions about ethics are. “I began to notice that students were less interested in debating the question of whether God exists than in discussing what to do and how to live,” Figdor writes in "Atheist Mind, Humanist Heart," a new book that he co-authored with Lex Bayer.

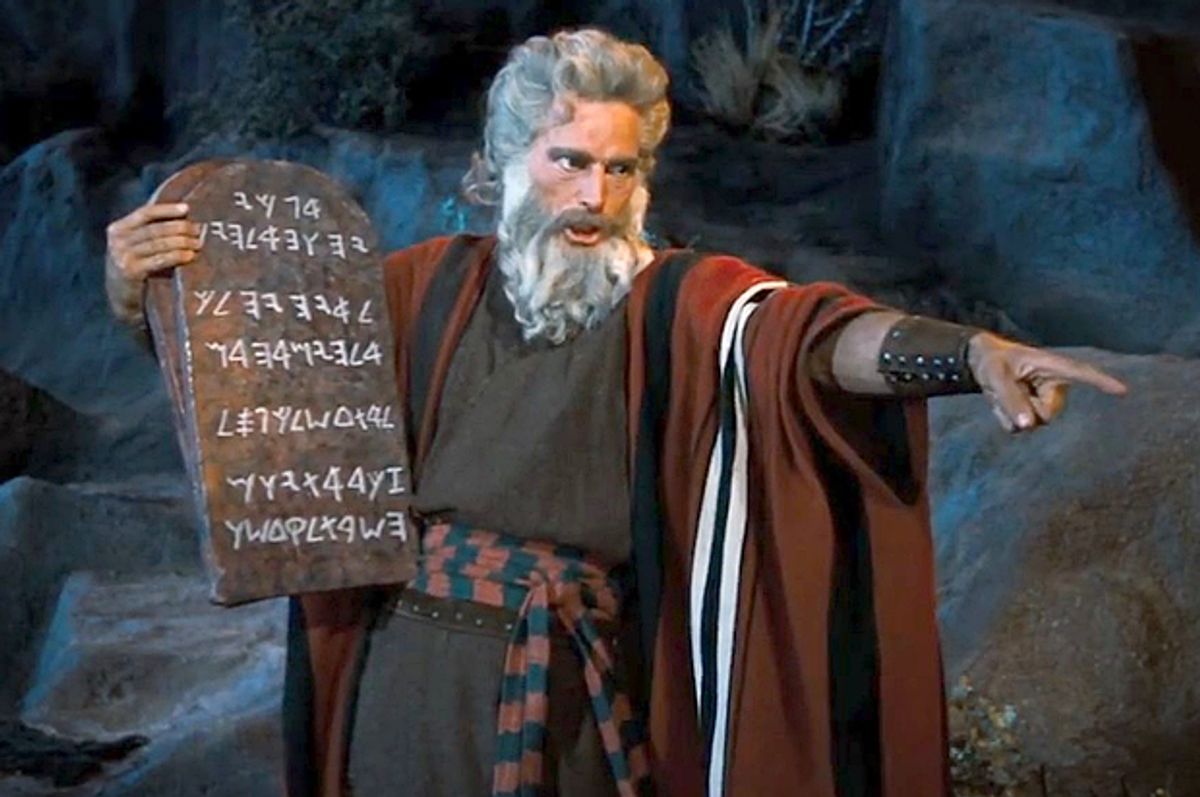

In step with many millennial atheists, Figdor and Bayer are looking for principles by which to live. In "Atheist Mind, Humanist Heart," they rewrite the Ten Commandments. Like the original set, Figdor and Bayer’s commandments are more than moral rules; they’re statements about cosmic order. Commandment IV: “All truth is proportional to the evidence.” Commandment V: “There is no God.”

The book launched at the end of October, and no divine being struck down Figdor and Bayer, a Bay Area entrepreneur and Airbnb executive who’s active in humanist circles. At its core, their book is a manual for ethical self-reflection in a secular age. The pair want readers to come up with their own sets of commandments.

To encourage that reflection, they’ve offered $10,000 in prizes to people who come up with their own sets of beliefs. Depending on your theological stance, the contest tag line — “Crowd Sourcing the Ten Commandments for the 21st Century” — will either give you great hope for our open-source ethical future, or encourage you to build a bunker in your backyard.

Over the phone, John Figdor spoke with Salon about religious law, crowdsourced dogma and the experience of sharing an office with two rabbis.

You're essentially rewriting the Ten Commandments, and you're calling on others to do the same. That takes some chutzpah. Were you nervous?

Not particularly. We're crowdsourcing alternatives to the Ten Commandments. Many people have done this in the past, and almost every revision of the Ten Commandments that I've seen has been better than the first draft. I think almost anyone can do better than the original 10.

What's the problem with the original 10?

Well, for secular people, people who don't believe in God … there's a significant number of the commandments that don't actually relate to human morality that relate to human relationships with God. And those are kind of missed opportunities, the way that I see it, to add in more moral commandments.

The original Ten Commandments was written before the invention of modern scientific knowledge and the scientific method. We wrote the original Ten Commandments without understanding psychology, neuroscience — with a very antiquated view of philosophy, without understanding evolutionary biology. We think that you ought to base your beliefs on the evidence, and as we have access to more information and more evidence, our beliefs ought to change.

You specifically call them "Ten Commandments for the 21st Century.” What is it about this particular historical moment that invites a rewrite? Or what is it about your version of the Ten Commandments that's specifically adapted to the 21st century?

Again, we’re trying to point out that the original Ten Commandments were written in, like, very early history. We're talking Stone Age texts. There're many points at which we probably should have updated the Ten Commandments. When we understood the germ theory of disease, we probably should have reworked the Ten Commandments. When we figured out the printing press, we probably should have worked them out. When we figured out basic evolutionary biology, all of these moments where we learn something new, we ought to reflect on our previous beliefs and say, "Do these still seem true? Do these still seem valid to us?"

But doesn't that already happen within the religious context? Reading your book, I felt like you had set up a straw man, in which religious laws were described as static, rigid dogma that hasn't changed in thousands of years. But certainly, if we look at, say, Jewish law, there's a constant process of evolution and legal wrangling, as people apply ancient laws to a new world. How do you account for that dynamism?

I think that you're seeing the dynamism in the liberal version of those religions. I don't think you see it in the conservative interpretations of those religions, first of all. And second of all, it’s right to think they changed, but they evolved so slowly. Take, for example, modern evangelicals and their objection to both deep time — say, that the Earth is older than 6,000 years old — and to evolutionary biology.

It's fair to say that religions evolve, and I come from the liberal church tradition where I see that completely. My church was pastored by an atheist at one point, or at minimum, a deistic agnostic. I certainly don't want to give you the view that I have a straw man view of religion. I mean, so frequently in the atheism discussion, religion just gets translated into following beliefs, following commandments directly — taking orders — and that's not actually how many people practice their faith. But it also is how around 40 percent of the American public practice their faith. So it's not a total distortion. But you're right, it's not the full picture.

Could this book be applicable for people who consider themselves believers?

Yeah, I think it absolutely is relevant to believers as well. Look, I may not agree with your starting assumption, if one of your starting assumptions is that God exists and that he sets truth and logic into existence. That's fine. I don't believe that, but if you still want all of your other beliefs to follow science and philosophy and rational thought and critical thinking, then absolutely you can apply the method to all your other beliefs.

The people that we're really targeting this to are people who have given up their belief in God and are wondering what's next. It's not our belief that everyone needs a secular Ten Commandments, or that everyone even needs to read a discussion about secular ethics. But it is our belief that over the years, a number of students have come up to me and said, "John, I've given up my belief in God, I don't believe in supernaturalism, but I want to figure out what I do believe in, what values are worth believing in."

I cannot stress enough that this is not our attempt to come up with a list of 10 that atheists just follow and then they're going to be good people. That's not at all the point.

What methods do you encourage people to use?

We think that you ought to follow a broadly scientific, critical-thinking methodology in thinking about your beliefs.

Do you agree with Sam Harris' argument that science can give us a set of absolute moral codes?

He says that science can give you objective morality, and I disagree.

So how do you differ from Harris’ approach?

I have huge respect for Sam Harris, and my position is actually extremely similar to Sam Harris’. We just come to two different conclusions. Sam Harris' position is, broadly, that we can look at something called the neurotypical behavior of human beings, and we can understand that when you have serotonin in a certain volume, or you have dopamine in a certain volume, this means that there's something positive going into your brain. So he has this standard for valuing things. A neurotypically derived version of utilitarianism.

Sam Harris has this view where we're able to generate an objective answer out of this. [Lex Bayer and I] don't think that it's objective, because ultimately it's based on the beliefs, experiences and preferences of individuals.

Those opinions are based on people's subjective experiences, and so you can't call them objective at the end of the day. But it is the closest possible thing we can get to objective ethics, which is that you take everyone's viewpoint into consideration.

I interviewed Rabbi Jonathan Sacks a couple months ago. He argues that it's actually pretty easy to figure out the right thing to do. The hard part is getting people to do it. For Sacks, that's where religion comes in. Do you feel like you’ve addressed that criticism?

Well, if his criticism is that moral problems are not difficult, and we need to just shut up and follow the conventional answers, that seems like a bad answer. When we're asking questions like, is A.I. consciousness real? Should computers have moral value? Or when we're talking about the idea of genetic engineering. These are enormously complex problems, and what I would say to the rabbi is that it's very difficult to have realistic and rational conversations about these problems with Stone Age beliefs operating in the background for about 40 percent of people.

My view is religion comes in and introduces a bunch of moral problems that wouldn't exist otherwise. There is a wonderful emergent religious left that's coming out, that's having really authentic and serious conversations about religion. But, unfortunately, they aren't the people having the conversation, and making it so that we can't really have a discussion about stem-cell research or abortion access or evolution.

I think that Sacks would say that part of the battle is figuring out what's right, but the more difficult part is building social structures that motivate people to do what's right.

The second point, that religion is a good way of providing a community for people, and a good way for us maybe to address these concepts in a context that works for people — oh, that's absolutely true. And that's why you see the profusion of humanist groups rising around the country, and the enormous proliferation of humanist chaplains.

When I started out in this business, there were five humanist chaplains. There was one at Harvard, one at Columbia, one at Rutgers, one at American University, and we were thinking about launching my organization [at Stanford]. Now, just a few years later, there's one at Harvard, Yale, Tufts, American University, Rutgers, the University of Southern California …

If two in five Americans are essentially secular, essentially do not participate in religious life except for, like, a wedding and a funeral, that changes our religious landscape in this country in an enormous way. I think we're on the turning point of people turning away and saying, “Look, religion is nuts.” It has a good concept, the congregational model seems to work pretty well, the community-building model seems to work really well, but its answers don't work anymore for people. That's what I see humanist chaplains doing, saying, “What’s worth preserving from the religious model, and how do we update this with modern science, philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, et cetera?”

What do you think is worth preserving from the religious model?

The idea of community, first of all. I’m sure you’re familiar with Robert Putnam’s study “American Grace,” which shows that religious Americans are better than secular Americans, because they donate more to charity, they donate more to secular charities, they vote in higher percentages.

I argue that this stems from the community aspects. It comes from people coming together and making a commitment publicly, and then holding each other accountable for that commitment. So when we raise money for leukemia and lymphoma research or do a blood drive or a bone marrow drive, that’s what’s operating in the background.

What do humanist chaplains do, exactly?

The first and most important thing that we do is advocate for the student perspective from within the Office of Religious Life, and ensure that the office isn’t creating programs that are explicitly hostile to secular students, so that [they] begin incorporating the humanist/atheist/agnostic view into their broad religious life programming.

The second thing we do is counseling — philosophical counseling, because there’s an enormous difference between what we do and what religious chaplains do. I will meet with anyone who wants to talk, but if you have an extremely serious psychological issue like suicidal thoughts or alcohol addiction or drug addiction, I’m going to insist that we work together with a psychologist and a team to provide care. Many traditional religious, a chaplain or minister or priest will simply decide they’re going to troubleshoot your alcoholism based on, I don’t know, a divinity degree, and that terrifies me, because you’re offering psychological counseling without a license and without advanced training.

Could you give me an example of a humanist community in action, taking on the kind of moral roles and responsibilities that you engage with in the book? Or how you would imagine, ideally, that that kind of community would look?

When I worked for [the humanist chaplaincy at] Harvard, we were able to run a program focused on Sept. 11 that we ran in conjunction with the Muslim community. As you know, there’s a lot of public bad blood between atheists — specifically new atheists — and Muslims. But this was not our experience. Our experience was that our students are not hateful, Muslim students are not hateful either, we should get together.

So we put on this great program where on the 10-year anniversary of 9/11 we made 10,000 meals. The point is, atheists and Muslims and Christians and Jews can all agree that no kid should be hungry. The first thing we agree on is that this is a moral problem that we can collectively work on. We may not agree with the blunt reasons why, but we agree that this shouldn’t happen.

The second is that it takes communities that had often been perceived as being in conflict and shows people that, yeah, of course there’s extremist beliefs in both of these communities that completely reject the other, but most atheists and most Muslims are good people who just want to work together to figure out how to improve the planet.

We’re able to challenge and inspire others to attempt similar things, and this is the interfaith model, the religions and non-religions coming together to work on these problems.

It’s interesting that you use the term “interfaith,” because almost nobody would call atheism a faith.

I think "interfaith" is the best word we can come up with at this point; you could say “inter-perspective” or “inter-worldview,” but I don’t think those quite cut it. I think eventually we’ll need a different term. Right now I’m willing to say, “OK, we atheists will take one on the chin and let you guys call it interfaith, because we think the broader goals of this are more important than our objection to the name.” But if in 60 years the tables turn and America is 60-70 percent secular and religion is in a minority position, we’re going to expect that to shift.

You’ve invited people to submit statements of belief — their own commandments — and you’re offering a total of $10,000 in prizes, which I gather has been put up by Lex Bayer.

Exactly. We decided not to split it 50-50 between the humanist chaplain who makes, like, nothing and the —

— and the venture capitalist.

Exactly.

That seems wise. Your tag line is “Crowd Sourcing the Ten Commandments for the 21st Century.” How are you going to pick the winners?

We've given judges a criteria list — things like, are these beliefs rational? Are they concise? Are they applicable? Are they universalizable? Are they relevant to more than one person? Things like that. I would encourage anyone to post, because Lex and I don’t actually choose the winners. We aren’t judges. The judges are people like Adam Savage from "Mythbusters" and Robin Blumner, the executive director of the Richard Dawkins Foundation. People like that.

I want to bring up some of the class dynamics here. The universities with humanist chaplains tend to be wealthier schools —

I don’t know if Rutgers is the wealthiest university, but it is true about the others.

Right. And a lot of atheist literature — by no means all, but a lot — comes from white, highly educated, affluent men. How applicable are your ideas outside of a certain group? How much are these really “Ten Commandments for Philosophy Geeks With Free Time"?

I think that, historically, atheist groups have had this problem where they’ve only elevated white guys like me to the front of those organizations, but now that it’s our generation making these decisions, we’re choosing to take the backseat — or to elevate some of these voices to make sure that they get into the conversation. I think the atheist movement in five or 10 years is going to look a lot [less like] an old white retirees group.

And the philosophy geeks with free time?

Well, [the book] is probably not super for philosophy geeks, because it’s pretty much an introductory book. The class point I think is real, and I think the problem is this: Right now, atheism is most strongly correlated with education. And right now, education is most strongly correlated with wealth. This is a byproduct of the curious place of American secularism and who it attracts, and I don’t think it’s true of the changing demographics

In the past, humanism has catered to these upper-middle-class groups but again, I think that’s a historical moment of felicity, and not something deep about the atheist view.

Looking forward, do you feel like the concept of morality that you and Bayer envision will invite partnerships with more liberal religious organizations?

I’ve found that it has in the past. Just this year, we’ve run three service projects, two of them in conjunction with religious groups. We’re trying to do this work already.

You share your office with a Reconstructionist rabbi and a Chabad rabbi. What’s that like?

We have a good time. We all enjoy "The Simpsons," so we have something in common. It’s also convenient because there’s such a strong core of secular Jewishness in atheist groups around the country that you can’t avoid it to a certain extent.

Our view — well, my view, I don’t really know what theirs is, at the end of the day — is that I’m not competing with them. Stanford campus is situated between San Jose and San Francisco. Both of those cities are 45 percent or more secular. As one person responsible for 40 percent of the Stanford student population, I couldn’t possibly cover all of that, even if I tried. So I’m not interested in also trying to peel students away from some of the religious groups. I’m just interested in creating positive programs for my group. I’ll tell you, we could use some help. I wish there was a skeptic chaplain on campus and I wish there was a secular-humanistic-Jewish chaplain on campus that we could work with as well.

But for now, you’re in the office with the rabbis.

Yeah, we’re good.

Shares