“Most dynasties are defined and circumscribed by region. The Roosevelts rode as high and far as the national fortunes of New York State. The Tafts go as far as Ohio takes them…. Not the Bushes. Their success is found in an essential rootlessness.”

– Michael Powell, Washington Post, 2001

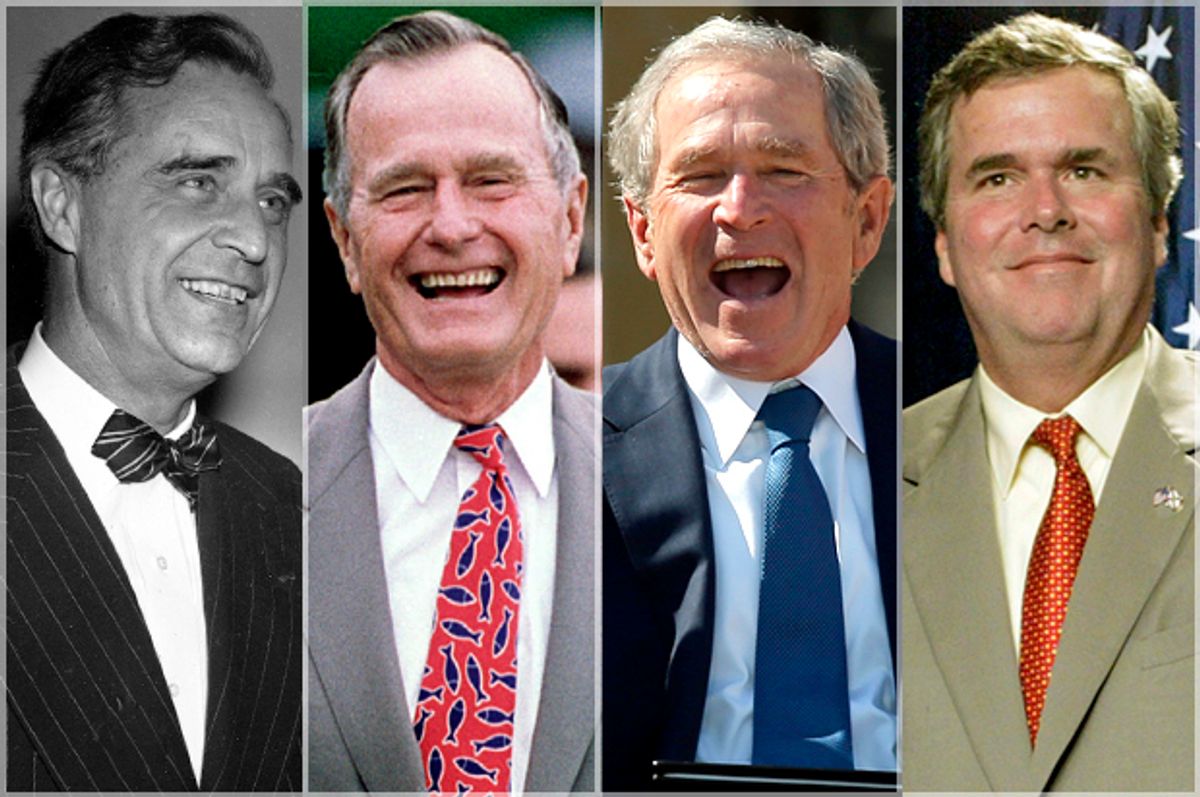

Jeb Bush’s announcement of a presidential campaign exploratory committee – and the gauntlet immediately thrown down by movement conservatives – might sound familiar to longtime political observers. But this is not merely because of its similarity to obstacles overcome by John McCain or Mitt Romney. It’s because the reception was nearly identical to that his own father received 51 years ago when he announced his campaign for the U.S. Senate. Indeed, the modern Republican Party’s evolution can be traced along the branches of the Bush family tree, as the ambitions of Bush men compelled a perpetual repositioning to appeal to the party’s activist base. Once a Northeastern and Midwestern party emphasizing fiscal prudence, cooperative multilateralism abroad and social moderation, the party became a Sunbelt party focused on deep tax cuts, international assertiveness rooted in American exceptionalism, and a cultural traditionalism skeptical of modern science while promoting religion in the public square.

The Patriarch

In many ways the Republican Party’s evolution begins with a political neophyte seeking an open U.S. Senate seat in Connecticut who was joined at a rally by a fire-breathing Wisconsin conservative. The New Englander, a stately former Skull and Bones member at Yale who became a wealthy and prominent Manhattan investment banker, was Prescott Bush, George W. and Jeb’s grandfather. The imported political talent who headlined the event was a vehement anti-Communist offering red meat and rough edges: Senator Joseph McCarthy. McCarthy was in Bridgeport to raise Bush's profile and fire up rank-and-file Republicans. But though he welcomed "Tailgunner Joe" to Connecticut, Pres later noted that he had “very considerable reservations… concerning the methods which he employs."

McCarthyism was not Pres Bush’s brand of Republicanism; indeed, Pres described himself as a "moderate progressive" concerned about the conditions in dilapidated urban slums, with which he had become familiar in his longtime role as state chairman of the United Negro College Fund. But his philanthropic efforts did not preclude a belief in the need for government support: once elected, Pres focused on affordable housing preservation, spearheading the 1954 Housing Act, which contained $150 million for 26 Connecticut cities, giving Connecticut more money per capita than any state. He exhorted Congress to "have the courage to raise the required revenues by approving whatever levels of taxation may be necessary" to fund education and research. He drafted legislation that expedited the construction of local flood protection works. He stood to the left of his party on everything from taxes and civil rights to infrastructure and immigration.

A Son Heads for Texas

Prescott’s son George H. W. Bush (“Bush”) left for Texas to make a name for himself outside of his father’s shadow. Bush moved his family to West Texas in 1948, during Texas’ first era of one-party rule, and started a company in the oil business. But by the time he decided to run for the U.S. Senate in 1963, he encountered a thriving Texas Republican Party. It had just elected its first United States Senator by prying conservative Democrats away from their ancestral home; perceived Democratic support of civil rights was anathema to many Democrats. Bush’s only problem was that the rank-and-file Texas Republicans were not much like the Connecticut Republicans who had elected his father.

According to Texas writer Molly Ivins, Bush would never truly be accepted in the Lone Star State, because "real Texans do not use the word summer as a verb … and do not wear blue slacks with little green whales all over them." Observing the 1964 race, Texas Observer editor Ronnie Dugger noted that Bush's campaign “gets its sparkle from the young Republican matrons who are enthusiastic about him personally and have plenty of money for baby sitters and nothing much to do with their time." Unfortunately for Bush, there were not enough of these types to nominate a Rockefeller Republican in a contested Texas primary.

Despite his East Coast upbringing, Bush was determined to fit in – whatever it took. He realized that whatever appearances might suggest, the substance of his campaign would need to be more Goldwater than Rockefeller. The party was changing, and the South was leading that change. Republicanism had come to the South from the top down, spawned in the silk-stocking suburbs of booming Rim South metropolises like Charlotte and Memphis by people not much different, culturally speaking, from the Bushes. But now, with the aid of Goldwater’s staunch opposition to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Republicanism was spreading like wildfire throughout the Deep South. The John Birch Society types who flooded Republican events were highly suspicious of the Manhattan financier cliques, and so Bush provided an easy target. Wrote Richard Ben Cramer in his classic "What it Takes":

“…[T]he nuts hated him. They could smell Yale on him. He was always saying stuff like, ‘We have the same basic goals…’ He couldn’t seem to get what was basic to the Birchers: being rid of him and everyone like him… like Eisenhower, Rockefeller… like all those rich, pointy-head, one-worlder, eastern-Harvard-Yale-country-club-Council-on-Foreign-Relations commie dupes!”

Bush strained to connect with the Birchers. He lambasted incumbent Democratic Senator Ralph Yarborough for voting to end the filibuster on the Civil Rights Act, which would, he claimed, destroy the judicial system. He proclaimed that if the United Nations seated the “Red” Chinese, the U.S. should “get the hell out” of the organization. He mused about ending all foreign aid except to arm the Cuban exiles. And he exalted capitalism’s virtues: "Only unbridled free enterprise can cure unemployment,” he said; capitalism “must be completely unfettered.” A proposal to establish a domestic Peace Corps was a “half-baked pie in the sky;” the federal government ought to abdicate all responsibility for alleviating poverty. Yet no matter how hard he tried, Bush never earned the right wing’s trust; even after his son was elected president, many conservatives still attributed George W.’s few moderate instincts to the insidious influence of his parents.

Bush lost the Senate race. But in 1966, the Republican establishment in Texas carved out a safe seat for him in a posh Houston area much more suited to his father’s style of Republicanism, and he won easily. Bush was in Congress when the 1968 Open Housing Act came up for a vote, and he decided to give each side a nod. Bush earned the wrath of conservatives in his district by voting for the final bill, but on the key procedural vote to send the bill’s toughest provisions back to committee, Bush sided with conservatives. Always, betwixt in between.

In 1970, Bush ran for the Senate again, running against conservative Democrat Lloyd Bentsen, who had ousted liberal Ralph Yarborough. With scant ability to draw contrasts, Bush lost again. He spent the next decade as Republican National Committee chairman, CIA director, and ambassador to China. In 1979, Bush began his quest for national office, and emerged as the moderate alternative to conservative darling Ronald Reagan, who had wowed the right with his spirited 1976 primary challenge. The primaries were a mismatch, but after their conclusion, Reagan confounded conservatives by choosing Bush as his running mate. Whereas Reagan had consistently espoused deep tax cuts, Bush had famously dubbed Reagan’s tax plan "voodoo economics." But now, he was part of Reagan’s team – a key step in the metamorphosis of the Bush clan.

George H. W. Bush: Transitional Figure

Whatever Prescott Bush's views, his son took his cues much more from Ronald Reagan than from his father once ensconced in the vice presidency. George H. W. Bush’s gradual transition was quiet, but by the time he stepped out into the spotlight at the 1988 GOP convention to become the Republicans standard-bearer, the "voodoo economics" line was replaced with his famous "Read my lips: No new taxes!" pledge. Bush had outflanked Bob Dole in the primaries (Dole had refused a similar pledge, instead promising to eliminate the deficit), and Bush delivered his convention rhetoric with a convert’s zeal.

Of course, that all changed with the recession of 1990, which caused Bush to reevaluate his pledge and approve a bipartisan compromise to raise taxes and reduce the ballooning deficit. The deal was widely repudiated by House Republicans, whose posture had shifted dramatically since Bush had served there. Then, Republicans had been a docile minority, vastly outnumbered by Democrats after the 1964 landslide and loathe to rock the institutional boat. But as the parties polarized, the House Bush encountered was a much different one. Whereas the House Republican leader, moderate Bob Michel, enjoyed a collegial relationship with Democrats and retained the loyalty of older Republicans, the norm of bipartisan comity was conspicuously rejected by his successor, Georgia bombthrower Newt Gingrich.

Throughout the 1990s, Gingrichites skewered Bush’s 1990 tax deal. When Bush left the White House in 1993, he had embraced bits and pieces of Reagan’s agenda. But although conservatives originally fancied his presidency as "Reagan's third term," he was unable to accomplish the sweeping tax, regulatory, or social changes they sought. He never adopted the overarching Reagan philosophy of limited government nor Reagan’s aggressive posture toward hostile nations. Despite his efforts, he never seemed like a true Texan, conservative, or “regular guy,” and his gaffes fed this perception, as when he blamed his poor 1987 Iowa straw poll showing on supporters who were “at their daughter’s coming-out party, or teeing up on the golf course.” He was a transitional figure: an ideological, geographic and cultural bridge from one Bush generation to the next.

This helps explain why George Bush struggled to connect with voters: he did not emanate a sense of place. He seemed forever betwixt and between his New England upbringing and his adopted Texas home. He never understood why he was so widely mocked for claiming to eat pork rinds, but any late-night talk show viewer immediately got the joke: he was trying too hard to be something he was not. It would fall to his son to complete the Bush dynasty’s evolution from northeastern Rockefeller moderation to evangelical Sun-Belt conservatism.

George W., Son of the South

When George W. Bush (“W”) first sought office in Texas, most people understood that his father’s central political problem had been his elitist bearing. In his own 1978 congressional bid, W faced similar issues. Democratic Rep. Kent Hance contrasted his local high school with W’s alma mater, Andover Academy; W exacerbated the problem with a commercial meant to highlight his vigor that showed him jogging, which he pulled after Hance noted that a West Texan would only be seen running if he was being chased. But by 1994, W learned his lesson. Having converted to evangelical Christianity, he incorporated religious imagery and themes into his speeches. Governor Ann Richards could not “out-Texan” him, and he upset her in a strong Republican year.

The Party of Fiscal Prudence Embraces Deficits

George W. Bush's first significant proposal as a presidential candidate was a $1.6 trillion tax cut, and his first major accomplishment was its enactment. It was originally designed to insulate him from 2000 primary rival Steve Forbes’s expected charge that he was, like his father, “soft” on taxes. Green-eyeshades Republicans were aghast at the plan, which resembled the “voodoo economics” his father had disparaged.

Upon his election, W sent his proposal to Capitol Hill and, given projected budget surpluses, garnered bipartisan support. However, negotiations highlighted fissures in the GOP that amplified Bush family differences, with Republican resistance centered in their ancestral New England, home to Maine Senators Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins, Rhode Island’s Lincoln Chafee and, fatefully, Vermont’s Jim Jeffords (who would soon switch parties, due in part to W’s rightward tilt, throwing Senate control to the Democrats). Prescott’s Republican descendants remained – and they held the balance of power, which they used to whittle the tax cut down.

Despite the September 11 tragedy and subsequent national security expenditures, W pushed a 2003 proposal to cut $1.5 trillion in taxes over 10 years (and create budget deficits larger than those experienced under Reagan). This push reshaped the Republican Party’s congressional wing. House Majority Leader Tom DeLay had in 1995 deemed a balanced budget – the centerpiece of the Contract with America – the party’s top fiscal priority and predicted a “calamity” without it. Unable to pass it, the House passed a resolution exalting the virtuous effects of a balanced budget, such as lower interest rates, faster growth, increased saving and investment and higher productivity. By 2003, leading House Republicans disavowed all that. Of course, had it passed, the constitutional amendment would have rendered the Bush tax cuts unconstitutional.

The inconsistency was just as glaring on the other side of the Capitol. In 1996, Senator Orrin Hatch had written that the balanced budget amendment was his "first priority… [because] continued deficits would devastate future generations.” But amid skyrocketing deficits in 2003, Hatch backed the tax cuts along with all but one Republican colleague, though just six years earlier they had all favored the balanced budget amendment. They apparently were persuaded by Dick Cheney’s logic that deficits “don’t matter.” The Bush-Cheney administration had transformed Republicans into a party heedless of mushrooming deficits – at least until the election of Barack Obama.

Culture, Religion, and Social Issues

At Home in Texas

If George H. W. Bush’s 1964 experience highlighted the cultural tensions he faced as a Yalie campaigning in Texas, then W did not seem to be conflicted. Religion helps explain this. W’s Christianity is not his parents’ mainline Methodist faith but an evangelical strain common in the South. During his 1994 gubernatorial campaign, W preached the gospel in Houston's mega-churches. He told the story of his 1986 awakening, tied to his liquor-soaked 40th birthday, the ensuing hangover and his snap decision to stop drinking.

In 1994, W espoused the “compassionate conservatism” theme he had once recommended to his father. George H. W.’s clinical detachment was immortalized in 1992 when he mistakenly recited the instructions from daily talking points. “Message: I Care,” he informed a confused crowd. But W’s rhetoric carried the zeal of southern evangelicalism, not the noblesse oblige of Prescott’s New England communitarianism.

These tonal differences suggested significant substantive differences. Bush family members had long preached compassion, but their prescription for government assistance evolved. Prescott sought to use both charity and the levers of government to ameliorate the plight of the needy. George H. W.’s signature proposal was simply for government to recognize a “thousand points of light” (i.e., local charities helping the less fortunate). W, though, merged compassion with social conservative activism by fusing it with religion through his “faith-based initiative” first espoused by John Ashcroft in the mid-1990s.

Religiosity as a National Figure

Most Americans first encountered W’s religiosity when, during a 2000 presidential debate, he was asked to name his favorite philosopher. “Christ,” he said, “because he changed my heart.” Pundits panned it as a transparent attempt to woo evangelicals, but it worked: W won a majority of them in the crucial South Carolina primary. As president, he delivered speeches laced with religious references. In 2003, he implored the nation to have faith in "the loving God behind all of life, and all of history." This departed from his forebears’ style; rare is the New Englander who publicly discusses religion. W’s language grew even more religious during the Iraq war. When author Bob Woodward asked him if he consulted his father, W replied that in seeking strength, “I appeal to a higher Father."

W’s piety shaped his social policies as well. An early executive order eliminated money for groups providing abortions overseas. He restricted stem-cell research, promoted abstinence education, implemented faith-based anti-poverty programs and supported measures to ban “partial-birth” abortion and define fetuses as people. “To truly change the culture,” he said, “we must have a spiritual renewal in the United States.”

The electoral calculations at play must be acknowledged. Strategist Karl Rove was obsessed with the estimated 4 million Christian conservatives who stayed home in 2000. But in 2004, W won 79 percent of 26.5 million evangelical votes. "Bush is the greatest president of my lifetime," said evangelical leader Richard Land. "[He] doesn't just understand our issues; he shares our worldview."

Melding Fiscal and Social Conservatism

George W. deftly intertwined economic and social conservatism. Compassionate conservatism could solve drug addiction, poverty, and homelessness – if only government would get out of the way. Government caseworkers demoralized the poor by merely handing them checks; church-run programs would transform the recipient’s soul. Herein lay the brilliance of W’s approach. It addressed the individual and not the state, which pleased fiscal conservatives who believed the solution lay in hard work; and social conservatives who believed the solution lay in accepting the Lord and shedding self-destructive “underclass” behaviors.

This approach had important implications. First, it reinforced long-established Texan norms about the proper role of the state. Government was not seen so much as a regulator of business as a facilitator, a lubricant for the pipelines through which money flowed. Compassionate conservatism justified further shrinking of government. If churches could operate more effectively than government, funding should follow, accelerating government retrenchment. In a state whose Legislature convenes for 100 days every year, this synched with the business establishment’s primary goal: to ensure that government does not grow powerful enough to hinder the prosperity of the state’s elite.

Second, W’s piety served as a perfect foil against the Clinton presidency, which began with allegations of infidelity and ended with confirmation of them. Bush's 1994 rhetoric of personal responsibility contrasted with Clinton’s serial evasiveness. After the Lewinsky allegations became public in 1998, W closed every campaign event by raising his right hand and intoning, “I will swear to uphold the dignity and honor of the office.” It was a deftly scripted morality play contrasting his own righteousness with Clinton’s laxity.

Finally, compassionate conservatism formed the basis for a presidential narrative by implicitly referencing his own recovery from years of heavy drinking and dysfunction. By rooting compassionate conservatism in his own redemption and assumption of responsibility, the slogan was a Rorschach test: Grover Norquist saw the possibility of government retrenchment, while Richard Land could see spiritual renewal sweep the nation.

Left in the dust was his ancestors’ Republicanism. Then-Republican Rhode Island Senator Lincoln Chafee embodied the dying Rockefeller wing in explaining his 2004 write-in vote for George H. W. Bush: "I'm a good Republican. And he had a good record on issues I care about: deficit reduction, the environment and foreign relations. It's very different than his son, the president."

***

In some cases, such as the green pants-clad George H. W. Bush’s maladroit 1964 attempts to appeal to Texas Birchers, Bushes have chased the party’s regional and philosophical shift. In other cases, Bushes have anticipated trends.

But today, Jeb Bush faces a dual challenge – the challenge faced by his ancestors, and the one faced by his brother. His centrist father and grandfather confronted a hostile party as conservatives disenchanted with Eisenhower’s moderation began forming a movement that would ultimately transform the party. His brother was culturally in step with the evolving Republican base, but faced the challenge of crafting a broadly appealing message that placated conservatives without alienating independents needed in the fall. Managing both challenges simultaneously in 2015-16 will be very difficult.

The historical parallels are certainly interesting. But perhaps most interesting is that less than a decade ago, Jeb’s current position was unthinkable. In 2005, Jeb was cast as the savior who prominent conservatives hoped would run in 2008 to avert the possible nomination of a moderate such as Rudy Giuliani or John McCain. Jeb’s gubernatorial record promoting tax cuts, school vouchers and a culture of life – whether that meant limiting abortion rights or suing to continue life support to a comatose patient – suggested that he would continue in the direction his family had moved for a half-century.

And yet since his brother left office, Jeb seems to be bucking the Republican Party’s long-term trajectory. He has instead sought to return the party to the genial moderation of his grandfather’s era. He’s committed heresy on immigration by embracing a pathway to citizenship for undocumented citizens, leading to snubs from leading evangelical activists. He’s staunchly supported Common Core, a K-12 education curriculum that has inflamed the base and led numerous other pols to flip-flop. And he has urged Republicans to repudiate Grover Norquist’s no-tax pledge and craft a bipartisan entitlement reform compromise.

With $17 trillion of debt, young voters may grasp that every dollar spent on baby boomers is a dollar from their pockets, which might boost their support of a nominee dedicated to entitlement reform. Given the increasing percentage of young voters in presidential elections, Republicans must appeal to them before their partisanship solidifies. And the steadily increasing percentage of Latino voters would clearly be more receptive to Jeb’s advocacy of a citizenship pathway than they were to Romney’s off-key self-deportation rhetoric.

If it were simply a math problem, Jeb could persuade his party to adopt electorally beneficial positions. But politics is not a linear equation: As I argue, it's about momentum and intensity within party coalitions. The newest elements to a party's coalition are its most vocal, and for today’s Republicans, that is the faction blocking electorally beneficial positions on taxes, entitlement reform and immigration. Rockefeller Republicans are the coalition’s oldest group and are dwindling fast; while they may support policy adjustments, they wield little clout and are the most culturally, geographically and ideologically distant from their party’s activist base.

The Bush family's evolution has neatly tracked the party's shifts for 50 years. But by stepping in front of the proverbial party train like a political Superman and willing it to reverse direction, Jeb’s “I won’t bend” approach differs sharply from that of his father and brother. We shall see if it works.

Shares