In the wake of Citizens United, large donors dominate the political landscape, with 84 percent of the money spent in 2014 coming from contributions greater than $200. The big money explosion is complete. In 1980 the largest political donor gave $1.72 million (in 2012 dollars); in 2012, the largest donor gave $56.8 million, or 33 times as much. It’s obvious that this big money bias favors the rich over the poor, but new research suggests it may also hamper racial equity.

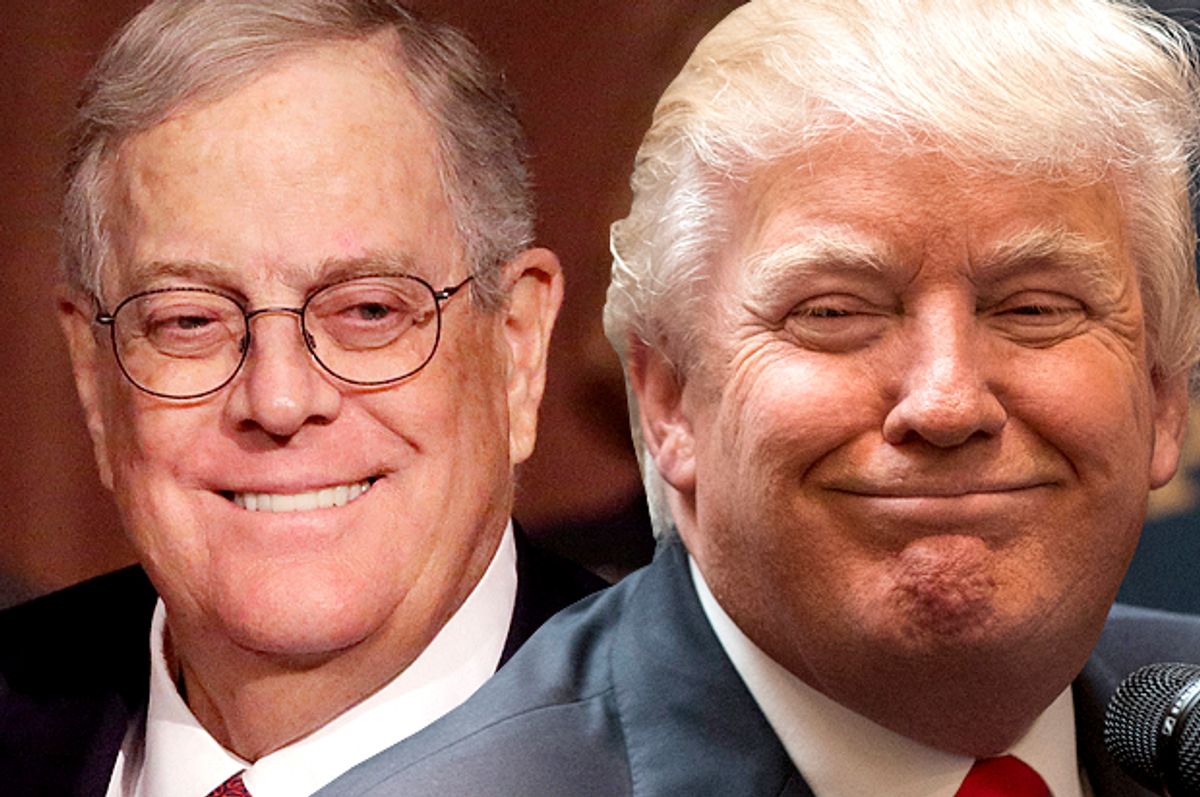

As money has come to play a larger role in politics, it has opened up the political system to the abuse of a few of the very wealthiest Americans, an ascendant donor class. However, due to racialized distribution of wealth and income in the United States, this “donor class” is overwhelmingly white (see chart).

This means that campaign contributions primarily come from white donors. An AP investigation of 2012 to super PACs and presidential campaigns finds that more than 90 percent of those contributions came from white neighborhoods. Demos' analysis of the top 10 Republican and Democratic donors finds that, “All of these donors appear to be white.”

These biases are important; gaps on issues like the budget deficits, inequality and paid sick leave break down more strongly on race lines than they do along class lines, for example. On other issues, there are salient racial divides, and political scientists find that people of color are better represented when their representative is of the same race (white legislators, even Democrats, are not as responsive). There are therefore substantial differences between white and nonwhite opinions on important issues, and it therefore is worrying that money in politics is so skewed toward white donors.

Campaign contributions matter for access and agenda-shaping. Research shows that campaign contributions from businesses can lead to lower corporate taxes. A study of the telecommunications industry finds that political spending leads to less stringent regulation. Recently, Christopher Witko finds that campaign donors are more likely to get a government contract. In a recent field experiment, donors were more likely to obtain a meeting with a Congress member. Campaign contributions and lobbying, then, not only influence whether a policy is enacted -- but whether that policy is even considered.

As Adam Lioz notes in the case studies he discusses in the Demos report, “When elected officials are dependent on corporate donors to fund their campaigns, business interests enjoy disproportionate sway over the policymaking process.” One case study is the private prison industry, which has benefited enormously from the incarceration boom. Between 1990 and 2009, the number of inmates housed in private prisons increased 17-fold (the number held in government prisons doubled). Investigative reporter Lee Fang has extensively documented how private prisons have taken over immigration detention and lobbied extensively for stricter immigration enforcement. The largest private prisons have spent millions lobbying at the federal and state level, particularly in periods during which immigration laws were under consideration. Lioz also links money in politics to predatory lending, which disproportionately impacted people of color and was left loosely regulated because of powerful monied interests.

As noted above, one way to increase the political system’s responsiveness to people of color is to get them elected into office -- but money in politics hampers progress here. A 2006 study of state legislative races finds that candidates of color raise far less money than white candidates, and the problem is worse in the South, where most blacks live. This hampers turnout: Political scientists Thomas Holbrook and Aaron C. find that in mayoral elections, “the effect of the total amount of campaign spending on turnout is notable.”

Without significant reform, the rich will gain a stranglehold on our political system. Recent developments, however, suggest that America is going in the opposition direction -- from adopting proposals straight from Citigroup lobbyists to the attempt to increase the cap on donations to political parties 10 times its current limit. Over the long term, Citizens United and McCutcheon need to be overturned, but with the current composition of the court this is unlikely. There are still reforms that can be made. Congress should pass the Disclose Act to stop the flood of dark money. Lobbying regulations have been shown to increase political equality. Public financing increases donor diversity and reduces the time candidates have to spend with big money donors. National parties should do more to recruit candidates of color and working-class candidates. Same-day registration would increase turnout among the poor and people of color, which research shows would combat the big money bias in our political system. The tough part about getting these reforms passed: They have to be passed by politicians who are already bought and paid for.

That doesn’t mean there is no hope. Evidence suggests that states with lower gaps in voter turnout have higher minimum wages, lower inequality and stricter lending laws. In Connecticut, the passage of public financing allowed Dannel Malloy to make paid sick days a core part of his campaign. Lindsay Farrell of Connecticut Working Families’ said that public financing “allowed him to be competitive in a race at that level without compromising on an issue like paid sick days.” In Minnesota, a grass-roots organizing campaign led by TakeAction Minnesota stopped an ALEC-backed photo ID law. Someday, there may well be a politician who, like FDR, says to monied interests, “We know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as Government by organized mob. Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.”

Shares