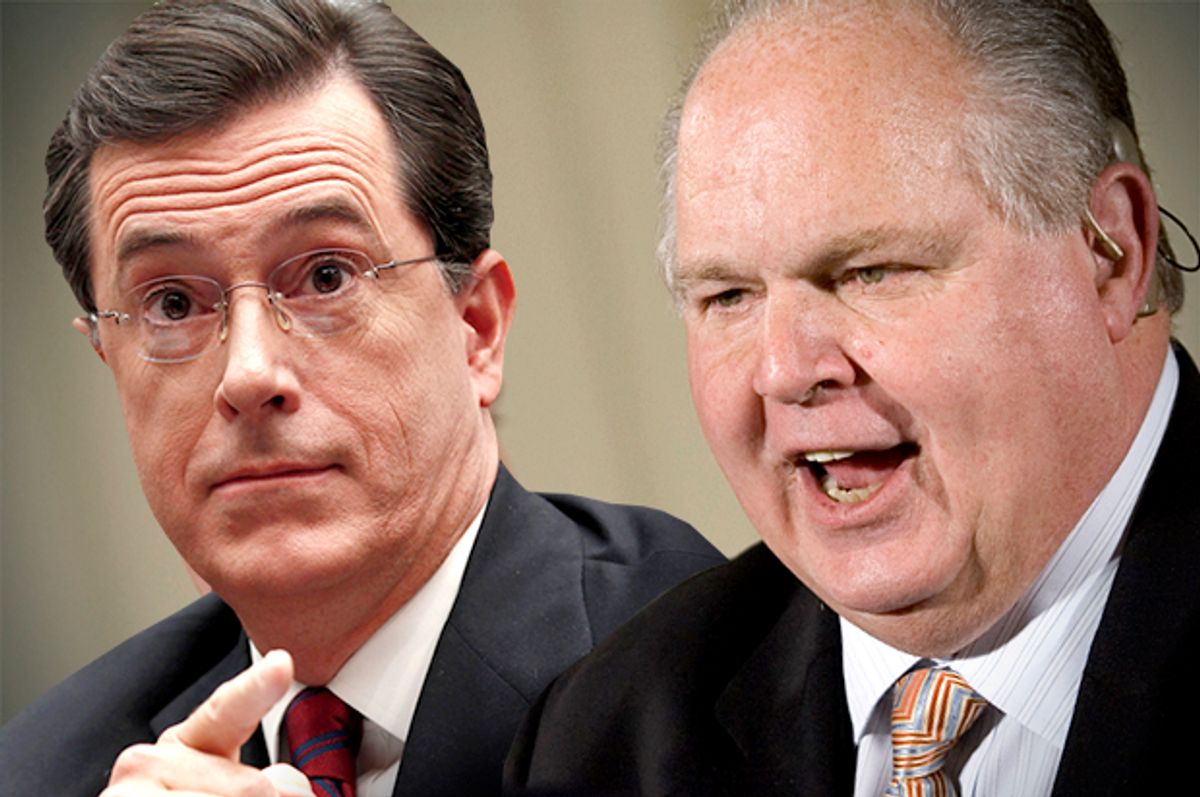

There seems little doubt that nuance, subtle thinking and critical insight are well beyond the grasp of Rush Limbaugh. So this piece is not directed at him. But the power of his arguments is real and the force they have in shaping public debate can’t be overlooked. So for that reason alone it seems worthwhile to debunk some of the arguments he made when he attacked the piece I wrote for Salon last week.

The core argument of my piece was that Stephen Colbert’s character from “The Colbert Report” had offered the U.S. public a refreshing alternative to the partisan spin of patriotism so often in play today. As I explained -- referring to the research of Geoffrey Nunberg -- in past decades, the right has dominated the discourse of what it means to care about this nation. And they have suggested that any questioning of the right is equal to treason. Colbert, I argued, exposed the fallacies of this view and reclaimed patriotism for his fans. A key part of the Colbert persona was his hyper-patriotism, and I pointed out that, as the character was put to rest, it was time to speculate on what this would mean for the future of left-leaning nationalism.

It is perfect irony that Limbaugh does, in fact, accuse me of attacking America. As he puts it, "I can't escape these professors and these lies and all this crap that's in the media about everything that's so-called wrong with America.” This was his response to a piece that indicated that Colbert had encouraged a large fan base to enthusiastically pursue their own version of what it means to be patriotic — one that we might argue has as much, if not more, affinity with the founding principles of our nation than the version offered by the right.

In fact, Colbert’s character often schooled Limbaugh on his understanding of U.S. history. In a bit from March 5, 2009, Colbert shows Limbaugh attacking Obama for supposedly violating the principles of the Constitution only to then quote from it. The quote, though, was from the Declaration of Independence. And Limbaugh actually gets that quote wrong: it is not “life, liberty, freedom, and the pursuit of happiness.” The word “freedom” does not appear there. This leads Colbert to conclude that he is applauding Limbaugh for “changing the Constitution” since “the liberals all want it to be a living document, but Rush took it one step further and made it a Wikipedia entry. He does not care what the Constitution says, which is final proof that he is the true leader of the Republican Party.” So, as Colbert gave his own viewers a lesson in U.S. history, he also showed us that one of the great so-called patriots of the right had his facts wrong.

One of Colbert’s greatest gifts was his ability to expose logical fallacies and faulty reasoning. His second book, "America Again: Re-Becoming the Greatness We Never Weren’t," epitomized one of the primary flaws in logic to conservative patriotism: How can the United States be the greatest nation ever and also be on the verge of total collapse? Or, as Limbaugh put it in his attack on me: “Meanwhile, we're losing everything this country's known for. The culture is rotting away, the culture is corrupting itself away, being perverted away, and all of that's being celebrated.”

Again and again, Colbert showed us that the right had created an almost devotional quality to their version of American exceptionalism, one that could not account for practical realities and one that could not handle any sort of questioning. If you asked about the treatment of Native Americans, then you hated freedom. If you thought that the U.S. should not practice unilateral foreign policy, you were weak. Any time anyone had a different view on these issues they were immediately attacked for “hating” their country.

It’s worth pausing to reflect on the very idea of attacking someone for “hating” their country when you disagree politically. How did politics become overrun with hyperbolic emotion? When Colbert began his show, much conservative political discourse had devolved to highly emotional language. There is no question that a degree of affect and emotion is a part of politics regardless of party affiliation, but most scholars of democracy agree that democracy works best when its citizens use reason and judgment to form their decisions.

This is why Colbert returned often to the idea that there was a difference between nationalism based on reasoned judgment versus emotional attachment. And he loved pointing out the hypocrisy of a party that claimed we all had to support our president when it was George W. Bush in office only to quickly reverse course and attack Obama from day one. As Limbaugh put it after Obama’s inauguration: “I hope Obama fails.” That doesn’t sound very patriotic now does it? But worse than that, Limbaugh often becomes angry and emotional, explaining his political views in terms of affect — fear, hatred, love and so on. Or, as Limbaugh phrases it, “All the stuff I’m steaming about.”

The core issue here, and one that Colbert consistently parodied, is the idea that blind faith and emotional attachment to nationalism are more consistent with fascism and fundamentalism than they are with democracy. Simply calling yourself patriotic does not make it so, which is why Colbert loved to used patriotic puns to describe himself — Megamerican, Lincolnish, Libertease, etc.

As Colbert’s parody of a right-wing pundit showed, a commitment to our nation’s democratic ideals requires engaged critical thinking. It also requires understanding that our nation has not always lived up to its ideals and that achieving equality and justice and tolerance requires active engagement on the part of us all. That, after all, is what defines democracy. Logic, reasoned judgment, engaged hope, these are all qualities that are also a key part of democratic political action. U.S. patriotism does not need to be defined by nostalgic love for a once-great nation that still is great -- as long as it doesn’t include anyone with a different view. Colbert used satire to show us that it was time to resist that version of our nation and push back.

This leads to another persistent flaw in Limbaugh logic: How can you claim to love your country, yet hate so many of its citizens? It turns out that people of color, women and folks who vote with the "Democrat Party" are all part of the very same nation that Limbaugh professes to love. And yet, he seems to have a never-ending ability to spit bile at his fellow citizens, constantly hurling invectives at those with whom he disagrees. Professorette? (His term for me.) Infobabe? Feminazi? And we can’t forget Limbaugh’s treatment of Sandra Fluke. Even better, watch Colbert’s take on it here.

There is nothing in the hate speech of Limbaugh that corresponds to any of the best ideals of our nation. We were better off getting our civics lessons from the satire of Colbert.

Shares