It’s taking a lot of strength to not make a “We’ve come a long way, baby” reference to kick off this piece. 2014, among all the other thing it was, was also the year that feminism, long simmering at the edges of politics, culture and media, boiled over into the mainstream, splashing into celebrity, commerce and beyond. It was a year in which the Nobel Peace Prize went to the young woman who had nearly died because she had the audacity to suggest that girls be given the same access to education as boys; a year in which the development of girls’ minds and self-confidence were at the center of marketing campaigns for Verizon and Always; a year in which the biggest pop star in the world pledged her allegiance (or, if you’re a bit more cynical, her brand) to feminism onstage at the MTV Video Music Awards. It was a year in which some of the biggest, most visceral debates about women’s full participation as humans in society took place online, via hashtags like #YesAllWomen, #YouOkSis, and #WhyIStayed and, perhaps less productively, in ethics-in-journalism clusterfuck #Gamergate.

Which is not to say 2014 itself was a feminist year. It would be more accurate to say that it was like most other years in that feminism, no matter how visible or hot a topic, was still treated simultaneously as a threat, a distraction, a scourge and a passing trend.

Which is why, amid year-end lists of the “39 Most Iconic Feminist Moments of 2014” and “The Greatest Moments for Feminism in 2014,” there’s mean-spirited clickbait like the list of “Top 10 Feminist Fiascoes” burped up by noted L.A. Times troll Charlotte Allen. Though one could argue that lists like Allen’s mainly prove that there are still a baffling number of women who don’t seem to understand that without feminism they probably couldn’t spew their analysis-free bile in a national news forum, it’s also evidence that mainstream media sees dollar signs in continuing to stoke antifeminist sentiment. So, in the spirit of an end-of-year assessment, I’d like to offer a by-no-means-exhaustive no-no list for covering feminism in 2015.

Feminism that takes place online is not “Twitter feminism.” It’s … feminism.

I’d like to think that 2014 marked a point at which no sentient person would still look around at social media and reason, “Yeah, but it’s not real life, is it?” And then Aaron Sorkin used Twitter’s success to literally kill off a character and I realized I’d been way too optimistic. So let’s resolve that 2015 will be the year that people, venerated TV scribes included, look at Twitter and see a site of active resistance, movement and accountability that is simply unprecedented in media. After all, it was largely social media that, three years ago, managed to stop the Susan G. Komen Foundation’s defunding of Planned Parenthood, and since then its users have done everything from putting the kibosh on a book by one of George Zimmerman’s jurors to embarrassing "Saturday Night Live" into finally diversifying its writers’ room to driving national conversations about domestic violence, racist team mascots and more. This moment in social media isn’t defined by feminism alone, but it’s inarguable that some of the most vital (and viral) activism, no matter what you think of it, is fomenting real-world change.

Your “Feminism meets Fashion!” headlines are not good.

There is a heady history of feminist fashion analysis, and even of fashion magazines that radically rethink clothing in the context of feminism and social justice. But there is no way truly feminist fashion is going to happen within the confines of the current industry, where sweatshop labor is the norm, a size 6 is considered undressable, and racism pervades every level from funding to casting. Karl Lagerfeld’s much-talked-about Chanel presentation, whose finale took the form of a feminist march, proved exactly why this co-optation falls flat, with daft slogans like “Free Freedom” and “Tweed is better than Tweet” (come again?) carried by an interchangeable clutch of white women, led by the man who called Adele “fat” and opined that “florals are for middle-aged women with weight problems.” Elle’s Anne Slowey, who seemed to be gunning for an alliteration prize with the headline “Finding Feminism at a Fancy Fashion Fete,” reached even further to find a feminist angle at a party for the jewelry brand Bulgari, finally concluding that some of the older women didn’t seem to have visible Botox. (That was one of the lesser-known demands of Seneca Falls, right?)

Stop using feminism to chum the waters.

It’s tough to be a media property these days, but the laziness of relying on antifeminist outrage-bait is more transparent than ever, and is an especially bad look on media properties that are increasingly progressive in other ways. To wit: Time, the same magazine that made history by putting a transgender woman, Laverne Cox, on its cover for the first time ever, six months later included “feminist” in a supposedly humorous list of words to ban in 2015. Katy Steinmetz, who penned both the article on Cox and the list, argued weakly that she wasn’t suggesting that the actions the word describes be banned, but it’s fair to say that equating a long-standing social movement whose tenets are still relevant to meme-born nonsense slang like “Om nom nom” might reflect poorly on a serious-minded newsmagazine. (That the list also included many words adopted from African-American Vernacular English didn’t do Time any favors, either.)

Ask celebrities a different question.

Nearly every female star who crossed a red carpet in 2014—not to mention a few male ones—were queried about their relationship to feminism. And sure, watching famous young women twist the definition of feminism in a dozen weird directions before disavowing it has been all kinds of fun, but I think we can be done now. Headlines like “Idiot Starlet Says Dumb Thing About Feminism, Feminists Freak” have accomplished very little besides some quality Twitter humor. One particularly unuseful result, however, is that their denials then unleash a torrent of think pieces designed to “gotcha!” them into an ideological 180. I don’t know that the world needs to know “The 21 Most Feminist Things that Shailene Woodley Has Ever Said”—wouldn’t the time it takes to write that piece be better spent on someone who is working to further feminism and not decry it?

The ultimate result, of course, is that the starlets in question develop an even warier relationship with feminism than they previously had. (With the exception of Taylor Swift, whom we’ll get to shortly.) That was likely the point of asking the question in the first place (see above re: chumming the waters), but let’s agree that everyone’s wise to the game at this point and, for 2015, pick a different hot-button political question to ask. What should it be? (I put this question out on social media, and got responses including “Where do you stand on torture?” "What's your sense of hope and opportunity for changing the inhumane system that you profit from?" and, my personal fave, “Cake or pie?”)

Be mindful to not treat celebrity feminism as the whole of feminism.

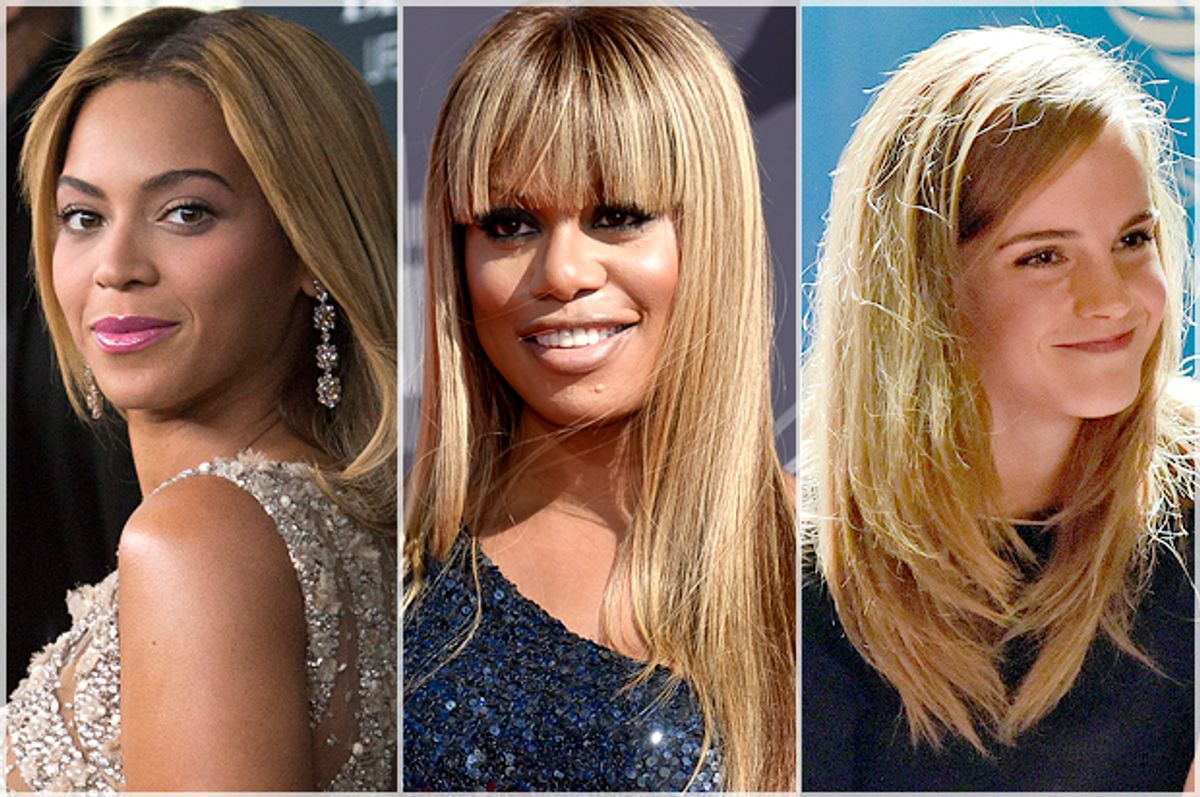

Last Friday, the Ms. Foundation for Women released a list of the “Top Celebrity Feminists of 2014,” a poll the foundation conducted in collaboration with Cosmopolitan magazine. At the top of the list was Emma Watson; Beyoncé came in at a somewhat puzzling No. 4, and Amy Poehler, Mindy Kaling and Cher (Cher?) were in there as well. Since its beginning, Ms. has corraled famous people to publicly get on board with feminist politics, so the list itself isn’t out of character. But the fact that 2014 was the first year to merit a list is notable in, perhaps unintentionally, pinpointing the gap between celebrity feminism and what I guess we now have to call “regular” feminism. And that difference is context. Emma Watson’s heralded U.N. speech reiterated something that feminists have been saying for decades—that liberation of humans from gendered roles and stereotypes benefits men just as much as women—but hearing it from someone who, the logic goes, doesn’t have to be a feminist but chooses to be makes it, somehow, more valid. The reason that Watson, Beyoncé, Jennifer Lawrence and other luminaries can drive spotlight to feminism is not just because they wrap it in a beautiful package, but because in aligning feminism with their own personal brands, they safely decontextualize it with broad statements and well-meaning speeches. That’s important, but it’s not the totality of feminism—as Roxane Gay noted in the Guardian last May, stars like these are “the gateway to the movement, not the movement itself.” Hopefully the mainstream media can keep that in mind before they write another headline like “9 Times Taylor Swift Was Right About Feminism in 2014” and “Beyoncé’s Hip New Club: Feminism.”

Stop asking “Is X the Most Feminist Show on TV?”

Whatever we’re talking about, this is almost never the right question. The fact that it’s been asked of almost every small-screen offering from "Scandal" to "Mad Men" to"Nashville" to "Orange Is the New Black" to "Game of Thrones" suggests that many of us really want some television that can be called feminist: Maybe we can talk more about that, rather than pitting things that are already in small supply against one another. And, for that matter, let’s declare a moratorium on the perennial questions of what things are and aren’t feminist. High heels? Short hair? Boyfriends? Girlfriends? Selfies? Up until now, there’s been no consensus and no answer that satisfies everybody, so, again, different questions are now in order.

If 2014 has taught us anything, it’s that a critical mass of people want to talk about whether and why feminism matters, but, as with too many arenas of public discourse, it ends up with people shouting past one another. It’s up to the media—us—to help change the frame and make 2015 the year that we further the conversation, not just rehash it.

Shares