“Time we may comprehend: ’tis but five days elder than ourselves.” So the 17th-century English writer Sir Thomas Browne summarized, almost casually, the profound question of the ultimate origin of our world, our species and time itself. In the age of scientific giants such as Galileo and Newton, most people in the Western world, whether religious or not, took it for granted that humanity is of almost the same age as the Earth. They also assumed that not just the Earth, but the whole universe or cosmos, and even time itself, are scarcely any older than human life.

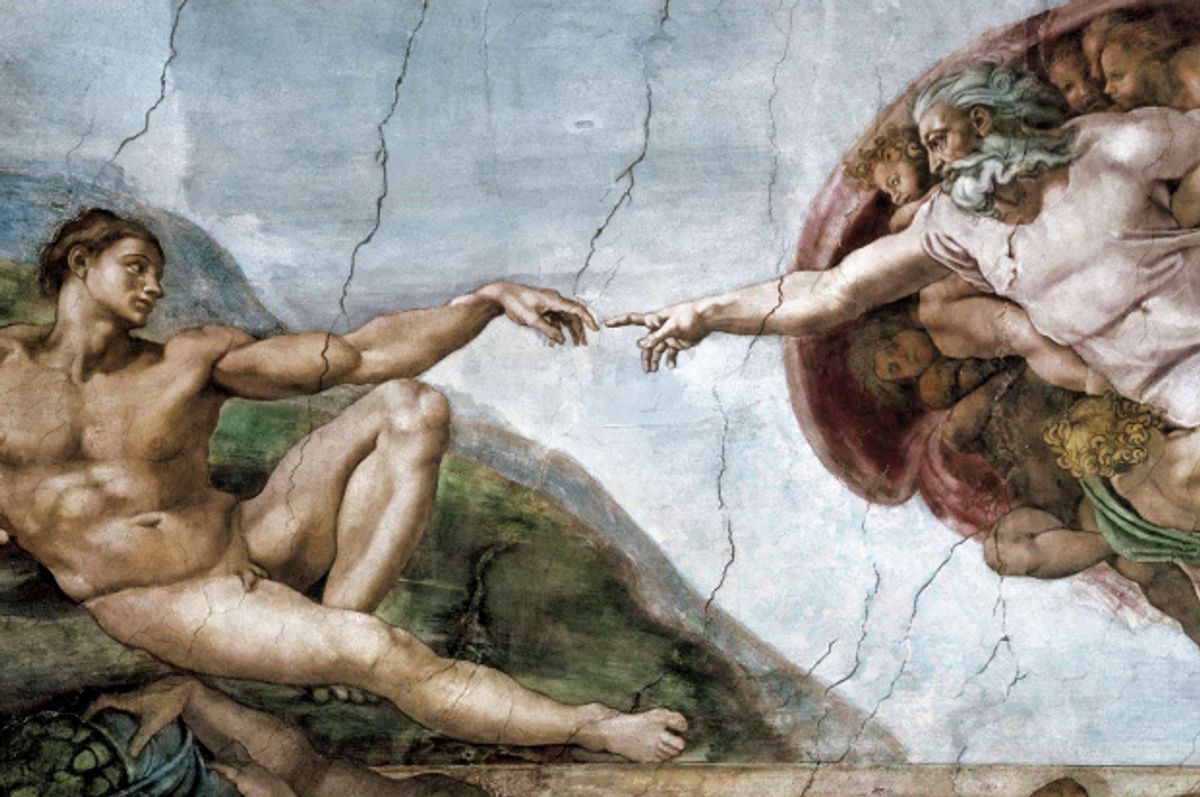

The opening chapter of Genesis, and of the Bible, set out a brief narrative in which Adam (“The Man”) had been formed on the sixth day of creative action, after five days of preparation and before God completed a primal week by resting on its Sabbath day. Browne and his contemporaries did not need a repressive Church to bully them into accepting this as a reliable account of the most distant past (and anyway, in a Christendom fractured by the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, there was no single all-powerful body capable of enforcing any such belief). It seemed obvious common sense to them that the world must always have been a human world, apart from a brief prelude in which the props necessary for human life had been put on stage: Sun and Moon, day and night, land and sea, plants and animals. A world without human beings would have struck them as utterly pointless, except as a brief setting of the scene for the human drama to come. So they took it for granted that Genesis gave them an authentic account of the world’s earliest origins. It came, they believed, from the hand of Moses, the only ancient historian to have recorded the earliest ages of the world; and the very first phase of that history—before any human being had been there to witness and remember it—could only have been disclosed to Moses (or to Adam before him) by the Creator himself. To cap it all, nothing in the world around them seemed obviously to suggest that its history had been otherwise.

Browne and most of his contemporaries, educated and uneducated alike, took it for granted that the history of humanity was of almost the same length as the history of the natural world. But far from thinking these histories were very short, and the Earth very young, they regarded both as extremely long, relative to brief human lives of, at best, some “three score years and ten.” History was plotted on a scale of the “Years of the Lord” (Anni Domini, AD) that had elapsed since Jesus’s birth, which was treated as the uniquely pivotal moment of divine Incarnation. Since that point in time and the time, some thirty years later, when the Roman official Pontius Pilate had ordered Jesus’s execution, more than sixteen centuries had passed into history. This was a very long span of time by any human standard; the study of the Romans and their highly respected Latin literature fully deserved its title of “Ancient History.” Yet the scale of “Years Before Christ” (BC) stretched even further back, past the ancient Greeks and their equally admired literature, to the obscure earliest ages for which the only surviving records were widely believed to be those in the Bible. Most historians reckoned that the primal Creation itself must be nearly three times as distant from the Incarnation as the Incarnation was distant from their own day. In total this amounted to an almost inconceivably lengthy history of the world. Some fifty or sixty centuries seemed more than enough time for the unfolding of the whole of known human history and also therefore for the natural world, the stage on which it had been played out. The world’s beginnings put even the “Ancient History” of the Greeks and Romans into the shade.

When one of these 17th-century historians calculated that the week of Creation had started on a specific day during the year 4004 BC, the date could be questioned, and was, but the precision aimed at was not. Nor was the order of magnitude thought to be an underestimate. This particular figure was published by James Ussher, an Irish historian whose powerful patron and great admirer had been King James I of England (James VI of Scotland). Shortly before that monarch’s death, he appointed Ussher to be Archbishop of Armagh and head of the established Protestant church in Ireland, though as it happened the scholar spent most of his later life in England.

In modern times, Ussher and his date of 4004 BC have been much scorned and ridiculed. But Ussher was not a religious fundamentalist in the modern mold. He was a public intellectual in the mainstream of the cultural life of his time. His work doesn’t deserve to be treated as a joke like those in 1066 And All That, the classic spoof history in which the English national story is studded with unmistakeable Good Kings and Bad Kings, Good Things and Bad Things. Ussher’s 4004 BC was not, in its time, a Bad Thing. On the contrary, what it represented was in some important respects a thoroughly Good Thing. Ussher’s view of world history may seem so far removed from the modern scientific picture of the Earth’s deep history that there can be no possible link between them, except as irreconcilable alternatives (which, in the eyes of modern fundamentalists, both religious and atheistic, is just what they are). In fact, however, what 17th-century historians such as Ussher were doing is connected without a break with what Earth scientists are doing in the modern world. Ussher is therefore a good starting point for understanding the origins of our modern conception of the Earth’s deep history. Moreover, once Ussher’s ideas are understood in the context of his own time, their superficial similarity to modern creationist ideas of a “Young Earth” is transformed into a stark contrast. The creationists, unlike Ussher, are out on a limb, and a precarious one at that.

In the 17th century Ussher was just one of the many scholars, scattered across Europe, who were engaged in the kind of historical research that was called “chronology.” This was an attempt to construct a detailed and accurate timeline of world history, compiled from all available textual records, both sacred and secular, including records of striking natural events such as eclipses, comets, and “new stars” (supernovae). Other chronologists criticized or rejected many specific details in Ussher’s timeline, but most of them shared his broader aims, and his compilation illustrates very well what they were all trying to do.

Ussher published his Annals of the Old Covenant (Annales Veteris Testamenti, 1650–54) near the end of a long and highly productive scholarly life. He wrote it in Latin, which ensured that it could be read by other scholars elsewhere: Latin was the common international language of educated people throughout Europe, just as English is today around the world. Ussher’s two massive volumes were entitled Annals because they summarized year by year what was known of events in world history; or at least he assigned each event to what he judged to be its correct year, and described them all in strict temporal order. So his book began with Creation at 4004 BC. But it extended forwards right through the BC/AD divide and the years of Jesus’s life, as far as the immediate aftermath of the Romans’ utter destruction of the great Jewish Temple in Jerusalem in AD 70. From Ussher’s Christian perspective, this marked the decisive end of the “Old Covenant” linking God specifically with the Jewish people. So his chronology traced the course of world history as far as the first few years of God’s “New Covenant” with the new people of God—in principle global and multi-ethnic—represented by the Christian Church.

Ussher’s world history embodied the best scholarly practice of his time. Chronology fully deserved its status as a historical science (using that word in its original sense, which is still current except in the Anglophone or English-speaking world). It was based on a rigorous analysis of all the ancient textual records known to him. These were mostly derived from sources in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Half a century earlier, the French scholar Joseph Scaliger, the greatest and most erudite chronologist of them all, had also used those in several other relevant languages such as Syriac and Arabic. But even Scaliger knew only a little about sources further afield, for example from China or India, and the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs had not yet been deciphered. Nonetheless, chronologists had available to them a massive body of multicultural and multilingual evidence. From all these varied records they extracted dates such as those of major political changes, the reigns of ancient monarchs, and memorable astronomical events. They then tried to match them up, often across different ancient cultures, and to link them together in a continuous chain of dated events. (The science of chronology is not extinct: the results of modern chronological research are on display in our museums, wherever artifacts from ancient China or Egypt, for example, are labeled with dates BC or BCE; all such dates are derived from similar correlations between the histories of different cultures.)

By far the greater part of Ussher’s evidence, like that of other chronologists, came not from the Bible but from ancient secular records. Not surprisingly, his sources were most abundant for the more recent centuries BC, and tailed off rapidly as he penetrated into the more remote past. For the very earliest times they were extremely scanty and almost confined to the bare record in Genesis of “who begat whom” in the earliest generations of human life. This makes it clear that Ussher’s main objective was indeed to compile a detailed history of the world, and not primarily to establish the date of Creation or to bolster the authority of the Bible in general. Ussher treated the Bible as one historical source among many, even if it was also, from his perspective, the most valuable and reliable of all.

Dating world history

Like other chronologists, Ussher adopted the sophisticated dating system that had been devised by Scaliger. The Frenchman had constructed a deliberately artificial “Julian” timescale from astronomical and calendrical elements. It provided a neutral dimension of time, as it were, on which rival chronologies could be set out and compared. It was not just a convenient device; it also highlighted the crucial distinction between time and history. Time itself was just an abstract dimension measured in years; history was all the real events that had happened in the course of time. What any chronologist claimed as real history could be plotted, on a baseline of the Julian scale, as “years of the world” (Anni Mundi, AM) counting forwards from Creation, or as “years before Christ” (BC) counting backwards from the Incarnation, from which the “Years of the Lord” (AD) were counted forwards. Research on chronology was powered by an intellectual craving for quantitative precision. This was characteristic of the age, and not confined to projects such as chronology. It was even more prominent in the natural sciences, for example in the contemporary work of astronomers such as Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler. In both kinds of investigation, quantitative precision was valued more highly than ever before.

Like cosmology, however, chronology was a highly controversial kind of research. Producing a dated timeline of events was fraught with problems of incomplete, ambiguous, or incompatible records. At one point after another, chronologists had to use their scholarly judgment to decide which records were the most reliable, and how they could most plausibly be linked together in an unbroken timeline. Consequently, there were almost as many rival dates for each important event as there were chronologists proposing them. This was particularly true for the date of Creation itself. Ussher’s 4004 BC was just one proposal in a crowded field ranging (according to one survey) from 4103 BC to 3928 BC. Scaliger, for example, had decided on 3949 BC, and Isaac Newton—a keen chronologist among many other things—later settled for 3988 BC. Ussher, like some other chronologists though not all, claimed a very precise date indeed, namely the start (at nightfall, according to Jewish timekeeping) of the first day of the first week after the autumn equinox; this marked the Jewish New Year equivalent to the Christian year 4004 BC. At the time, complex calendrical and historical reasoning made this kind of precision a perfectly respectable ambition, however bizarre it may seem to us.

It is only by historical accident that Ussher’s 4004 BC has become the best known of all such dates and now the most notorious, at least in the English-speaking world. Almost half a century after Ussher’s death, a scholarly English bishop included a long string of Ussher’s dates among his own editorial notes in the margins of his new edition of the “Authorized” or “King James” translation of the Bible into English, which had originally been published with the authority of Ussher’s royal patron back in 1611. Ussher’s dates remained there, by custom or inertia, in successive editions of the Bible in English, right through the 18th century and most of the 19th, although they were never formally authorized by either church or state. Darwin and his English contemporaries, for example, would have grown up seeing 4004 BC printed on the very first page of their family Bibles. Many young or uneducated readers, not understanding the role of an editor, assumed that the date was an integral part of the sacred text, and they respected or even revered it accordingly. Only in 1885 were all Ussher’s dates—by then long obsolete, in historical as well as scientific terms—omitted from the margins of the new “Revised Version” of the Bible. This was the first complete English translation to incorporate the greatly improved linguistic and historical understanding of the texts that was the fruit of biblical research by Jewish and Christian scholars since the time of Ussher (and King James). Readers of the Bibles placed by the Gideons in hotel bedrooms had to wait even longer, until the late 20th century, to be relieved of the implications of 4004 BC. In contrast, marginal dates did not usually feature in Bibles in other languages, so people outside the English-speaking world were generally spared this disastrous misapprehension that the exact date of primal Creation had been fixed by divine, or at least ecclesiastical, authority.

Periods of world history

To return, however, to Ussher’s century: his and other chronologists’ efforts to compile rigorously precise “annals” of world history were a means to what most of them regarded as a more important end. Quantitative precision was intended to help yield qualitative meaning. Chronologists wanted to give precision to what they saw as the overall shape of human history, by dividing it into a meaningful sequence of periods. The primary division represented by the traditional dating system of years BC and AD was just such a distinction, for it separated the old human world before the Incarnation from the radically new human world which—from a Christian perspective—that unique event had first brought into being. But Ussher, like other chronologists, also subdivided the millennia of BC history, by defining a sequence of decisive events or “epochs,” which in turn marked out a sequence of distinctive “ages,” “eras,” or periods. Ussher identified five significant turning-points between the mega-events of the Creation and the Incarnation. These ranged in time from Noah’s Flood to the ancient Jews’ deportation into exile in Babylon. Adding the period since the Incarnation, world history could then be divided into a sequence of seven ages. These were often taken to match, or echo symbolically, the sequence of seven “days” in the week of Creation itself. So the whole shape of world history was deeply imbued with Christian meaning.

In the 17th century, then, world history was pictured qualitatively as a sequence of distinctive periods bounded by particularly significant events, each of which chronologists tried to date accurately on a quantitative timescale. All this history was taken to be, most importantly, one of cumulative divine self-disclosure or “revelation,” but it was also largely human history. The non-human world of nature was treated for the most part just as a setting for the human drama, an almost unchanging background or context for human action and divine initiative. Only occasionally did events in the natural world feature prominently in accounts of human history, either sacred or secular. In the sacred story, for example, the waters of the Red Sea had retreated temporarily, enabling the Jewish people under Moses’ leadership to make their Exodus from Egypt and gain their freedom. Equally conveniently, or providentially, the Sun “stood still” for an embattled Joshua (though what exactly that meant was much debated); later still, Jesus’s birth and death were said to have been marked by, respectively, a new star and an earthquake.

Only at two points did the natural world feature still more prominently, right in the foreground of the sacred story. These two points were the Creation itself, and Noah’s Flood. In the 17th century, each was the focus of a distinctive kind of historical commentary, which to a limited extent enlarged the scholarly study of texts with materials drawn from nature.

The first kind of commentary was on the six “days” or phases of Creation. The brief narrative in Genesis was often used as a framework for reviewing what was currently known about the structure and functions of the cosmos, the Earth, and plants and animals, all of which jointly constituted the environment of human life. These commentaries (known as “hexahemeral” or “hexameral,” from the Greek for “six days”) followed what was taken to be the primary meaning of the biblical text. They treated the origins of the major features of the natural world as a coherent sequence of historical events in real time. The narrative was taken to be describing the sequence in which the props had been placed on stage, as it were, before the human drama could begin. So any such review of the environment of human life was not only a kind of natural history—an inventory or systematic description of nature—but also an account of origins that claimed to be nature’s true history (in the modern sense of that word). However brief the time-span of Creation was thought to have been, the story did ascribe to the natural world its own history, divided into a sequence of distinctive periods (the six “days” of the narrative) culminating in the appearance of human beings. It should be clear enough that this conception of world history was—despite the obvious huge contrast in the kind of timescale envisaged—closely analogous to the modern view of the Earth’s deep history, with its similar succession of major events and new forms of life. To point this out is not to claim that the Genesis account anticipated the truth of the scientific account, but just that the way it was interpreted in the 17th century was structurally similar to modern ideas about the Earth’s history. The Genesis narrative therefore pre-adapted European culture to find it easy and congenial to think about the Earth and its life in a similarly historical way.

Noah’s flood as history

Noah’s Flood or Deluge (described later in the book of Genesis) was treated even more clearly as a real historical event: on the chronologists’ calculations, it could be dated to more than a millennium and a half after the start of the human drama. Unlike the Creation story, its details did not depend on direct divine revelation. They could have reached Moses—who was believed to be the author of Genesis— through an unbroken line of records or memories stretching back to Noah and his family, who had been on board the Ark and had witnessed the Flood at first hand. So the story of the Flood was subjected to detailed analysis by scholars, who tried to work out what exactly had happened and how. They tried to reconstruct the “antediluvial” (“before the Deluge”) human world that the Flood had destroyed; how Noah’s family had survived the catastrophe in his Ark; and how the “postdiluvial” (“after the Deluge”) human world had recovered from it. They also conjectured how it might have been caused and how it had affected the Earth itself and its animal inhabitants and other non-human features. All this was based on the biblical text, mainly because Genesis was believed to contain the sole authentic historical record of the event (similar non-biblical stories, such as Deucalion’s flood in the Greek records, were generally thought to be second-hand accounts derived from the earlier biblical one, or else accounts of later and more local events).

Among the many 17th-century historians who analyzed and commented on the Flood story in this way, the German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher is a good example (just as Ussher has been taken here as a representative chronologist). Kircher was a highly erudite scholar who published on a wide range of topics of interest to his educated readers around Europe; like Ussher he wrote in Latin, making his work accessible to them all. His massive illustrated book on the The Subterranean World (Mundus Subterraneus, 1668), based on a wide knowledge of the natural sciences of his time, described the physical Earth as a complex system, dynamic but not in any sense a product of history. For example, he speculated how its visible surface features such as volcanoes might be related to its unseen internal structure (he had traveled in Italy and had first-hand knowledge of Vesuvius and Etna). But he did so in rather the same way that the surgeons and physicians among his contemporaries were working out how the visible features of the human body were related to the unseen organs within. Kircher described the Earth’s anatomy and physiology, as it were, but he did not describe it as having had any significant major changes or history since its initial creation.

The Flood, however, was the great exception. In another massive volume, Noah’s Ark (Arca Noë, 1675), Kircher analyzed the Flood historically, using his impressive multilingual skills to exploit all the known ancient versions of the biblical text. He worked out how Noah had built the Ark and embarked with its cargo of varied livestock; how the rising Flood had floated the Ark away and eventually dumped it on the summit of Ararat as the waters subsided; and how the human world had started up again in the postdiluvial period. From the data given in Genesis, he reconstructed, and illustrated in detail, the likely form and size of the Ark. He tried to work out how it could have accommodated even a single pair of every known animal. This gave him a reason to embellish his account with pictures of a wide range of these living animals (in effect, giving his readers a “natural history”). Since the Flood was said to have been worldwide, he also calculated how much extra water would have been needed to raise sea level globally, enough to cover the tops of the highest known mountains; and he speculated about where it might have come from and gone to, unless, implausibly, it was created and then eliminated specially for the occasion.

What is most significant in the present context is that Kircher, like some other scholars, also conjectured that the distribution of land and sea before the Flood might have differed from the form of the continents and oceans after that great event. The Flood might have changed the physical Earth substantially, in no less real a sense than it had changed the human world. At least at this point he was claiming, in effect, that the Earth had a true physical history to parallel its human history. However, as the title of his book implied, his erudite analysis was focused primarily on Noah and his Ark, and only secondarily on the physical effects of the Flood itself. His work belonged, in the main, to the same world of thought as that of scholarly chronologists such as Ussher: history was primarily a human story, and by modern standards a brief one.

The finite cosmos

One practical advantage of the artificial Julian timescale, as chronologists saw it, was that it spanned a total period long enough to accommodate any plausible calculation of the date of Creation at one end, and any anticipated date of the ultimate completion of world history at the other end, leaving plenty of virtual time to spare, as it were, at both ends. It was this that made it convenient as a dimension on which rival chronologies could be plotted and compared. But it also highlights what is, to modern eyes, surely the most unfamiliar feature of Ussher’s (and Scaliger’s) kind of chronology. This was not that it was very short by our modern scientific standards (though extremely long in human terms), but that it outlined a world history that had finite limits, both past and future. In this it was strikingly similar to the “closed world” of the traditional spatial picture of the cosmos—with the Earth at its center and all the stars around its periphery—which had been equally taken for granted until astronomers such as Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo began to open it out into a spatially infinite universe. However, Kircher and many other scholars in his time remained sceptical about that new picture of the cosmos, which they felt had yet to prove itself.

Ussher and most of his contemporaries believed that they were living in the world’s seventh and last age. Its final End was widely thought to be imminent, or at least it was expected in the foreseeable future. One common opinion was that the world might end with the completion of exactly six millennia from the Creation (that is, on Ussher’s figures, in 1996!). This matched Ussher’s calculation that the pivotal point of the Incarnation had been precisely four millennia after the Creation (it had long been recognized that the traditional scale was not quite correct on the real date of Christ’s birth, which was put at 4 BC). Such precision, heavily laden with symbolic meaning, made Ussher’s figure of 4004 BC particularly attractive to many of his contemporaries; he was not the first or the only chronologist to propose it.

Ussher emphasized and was proud of his achievement, yet he was well aware that his claim was controversial. As already mentioned, many different dates for the Creation were proposed, but not all chronologists were convinced that any such date could be fixed. Ever since the early centuries of the Christian (or Common) era, some scholars had pointed out that the Sun, the apparent movement of which defines ordinary days, had not been created until the fourth “day” of the Genesis story. So it had often been suggested that the seven “days” of Creation might not denote periods of twenty-four hours at all. Instead they might represent divinely significant moments, rather like the future “day of the Lord” in the recorded sayings of the Jewish prophets (our use of phrases such as “in Darwin’s day” is indefinite in rather the same way). If so, the “week” of Creation might have been of indeterminate duration, and its starting and ending dates might be even more uncertain. In other words, this biblical text, like others, was seen to require interpretation. Its meaning could not simply be read off unambiguously, as if the plain or “literal” meaning was self-evident and beyond argument. This recognition that scholarly judgment was needed, to interpret the meaning of texts, led chronologists and other historians to develop methods of textual criticism that continue to underlie historical (including biblical) research to the present day; “criticism” was of course used here in the same sense as in artistic, musical, or literary criticism, without any necessarily negative connotations.

The interpretations of 17th-century scholars may strike us now as extremely literal in character, but this is partly because they were taking the biblical texts seriously as historical documents. However, the strongly marked “literalism” of their approach to the Bible, far from being an ancient tradition, was a quite recent innovation. In earlier centuries many other layers of meaning—which might be termed symbolic, metaphorical, allegorical, poetic, and so on—had been prominent and generally more highly valued than the literal. But they had sometimes been elaborated so fancifully that, particularly in the Protestant world in the wake of the Reformation, they were downplayed or stripped away altogether, leaving the supposedly simpler “literal” meaning supreme. Yet Protestant scholars, no less than Catholics, conceded and indeed emphasized that their interpretations of biblical texts were intended primarily to elucidate practical meaning based on theological understanding, not to impart knowledge of nature.

In the case of the Creation story, for example, what was thought to be of ultimate importance was not its exact date, or the duration of its “days.” Far more significant for human lives was its assurance, in effect, that all things had been freely created by the one and only God, who had pronounced them all to be intrinsically “good”; that the sequence of creative actions had not been arbitrary but underlain by the consistent purposes of a caring God; and that no created thing—not even angels or other heavenly powers, let alone the Sun or Moon or other natural entities—should be treated as ultimate in value or deserving of worship. Themes such as these had been the stuff of both popular sermons and scholarly commentaries on Genesis, ever since the early Christian centuries. The theological meaning of the texts, and their application in the practice of Christian faith, had been emphasized endlessly, taking priority over any use they might have as sources of factual knowledge about the world’s origins. (The historically recent rise of literalism, and the continuing primacy of theological meaning in biblical interpretation, are often overlooked or ignored by modern fundamentalists, religious and atheistic alike.)

The exact date of Creation was not the only unresolved problem lurking behind the chronologists’ confident dating of world history. Although Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions could not be deciphered, there were ancient Greek reports of what had been known at that time. According to these, Egypt’s early dynasties stretched back many centuries before the generally favored dates for the Creation. The two sources of alleged evidence—Egyptian and biblical—could not both be correct, so chronologists had to choose between them. Once again, scholarly judgment was needed. It is hardly surprising that the biblical record was treated as the more reliable. The Egyptian record of allegedly pre-Creation history was generally dismissed as political spin, as a fiction devised long ago to bolster the legitimacy or prestige of Egypt’s ancient rulers. Equally unsettling, however, were some of the early Chinese records, when research by Jesuit scholars living in China first made them known to other Europeans. These records too suggested a much longer ancient human history than the chronologists’ calculations allowed. And ancient Greek reports of Babylonian records, though generally dismissed as fictitious, claimed even greater antiquity for human civilizations.

Most unsettling of all, perhaps, were the conjectures contained in a small book published just after Ussher’s huge Annals. The author of the anonymous Men Before Adam (Prae-Adamitae, 1655), which soon became widely known and indeed notorious, used a subtle interpretation of a specific New Testament text to argue that the biblical story of Adam was originally intended to refer to the first Jew, not the first human being. This put a big question mark against all chronologies based on Adam as the starting point for human history. The conjecture had the advantage that it could explain how the human races around the world might have had time to become so widespread and diverse. The sheer variety of humanity had not been fully appreciated by Europeans until, little more than a century earlier, their great exploratory voyages had first taken them around Africa to Asia and across the Atlantic to the Americas. Conversely, however, the conjecture had the disadvantage that it seemed to deny the unity of humankind in the Christian drama of salvation. For example, it appeared to exclude the indigenous peoples of the Americas from that drama, and thereby denied them fully human status. The claim that there had been “Pre-Adamite” human beings got its author—whose identity had been disclosed as the French scholar Isaac La Peyrère—into trouble with the Catholic authorities, though after renouncing such speculations, at least nominally, he lived to a peaceful old age.

The threat of eternalism

In the present context, however, the importance of Pre-Adamite ideas is that they added to the impact of the allegedly ancient Egyptian, Chinese, and Babylonian records. They all implied that the totality of human history might be far longer than any conventional Western chronology allowed, stretching back not five or six millennia but perhaps more than ten, or even—if the Babylonian records were to be believed—many tens of millennia. All this was disturbing to conventional thinking: not primarily because it put the dating of Creation or the authority of the Bible in doubt, but far more because it seemed to open the door to a much more radical kind of speculation. It suggested that ancient Greek philosophers such as Aristotle and Plato, whose ideas on other topics had long been revered in Europe, might have been right in this: they were taken to have claimed that the universe, and with it the Earth and human life, are not just extremely ancient but literally eternal, without any created beginning or final end. This was profoundly disturbing, because to deny that human beings are in some sense created, and therefore morally answerable to their transcendent Creator, seemed equivalent to denying that they have any ultimate responsibility for their actions and behavior. It seemed to threaten the very foundations of morality and society.

At first glance, this “eternalism” (as it has since been named) might seem to anticipate the modern picture of a history of the Earth and the cosmos measured in billions of years, in sharp contrast to the chronologists’ short and finite story measured in mere thousands. But the apparent modernity of eternalism is deceptive and deeply misleading. In fact, a “young Earth” and an eternal one, which were the only two alternatives considered in the 17th century, were equally un-modern.

Both assumed that human beings have always been and will always be essential to the universe. Although the chronologists’ short and finite history of the Earth (and of the cosmos) included a very brief pre-human setting of the scene, it was otherwise wholly a human drama from start to finish. But the eternalists’ picture, likewise, was of an Earth (and a cosmos) that had never in the past been without human beings, or at least some rational Pre-Adamites, and never would be in the future. Those who argued for the authenticity of extremely early human records from Egypt, China, or Babylon, way back beyond the usual range of plausible dates for Creation, assumed that even these were just the most ancient that had happened to survive. They took it for granted that there must have been a long or even infinite sequence of still earlier human cultures, of which all traces had been lost in the mists of time.

So the infinitely ancient Earth (and universe) of eternalism did not anticipate the modern scientific picture of an immensely lengthy but finite history of the Earth (and of the universe). Yet at the time, in the 17th century and even later, eternalism did offer a radical alternative to what was then the culturally dominant picture of a probably brief and certainly finite universe. Eternalism was widely regarded as subversive, socially and politically as well as religiously. So it generally remained, as it were, underground: it was most often visible when it was attacked by its orthodox critics, rather than being expressed openly by its unorthodox proponents. What was perceived as the radical threat to human society posed by eternalism goes a long way to account for the dogged defense, in some circles though not all, of the “young Earth” derived from a very literal interpretation of the Creation story in Genesis. Conversely, however, eternalists often had their own—religiously sceptical or even atheistic—agenda to promote. So this was certainly not a straightforward struggle of enlightened Reason against religious Dogma. There were strong “ideological” issues at stake on both sides of the argument.

On a global scale, however, the idea of an indefinite or even endless sequence of human lives, as implied by eternalism, had been the norm rather than the exception. Most pre-modern societies around the world embodied in their cultures an assumption that time—or rather, the history that unfolds in time—is repetitive or in some sense cyclic, not arrow-like or uniquely and irreversibly directional. Underlying this assumption, and making it seem common sense, was the universal experience of the cycle of individual lives from birth through maturity to death, repeated from one generation to the next. This was powerfully reinforced by the annual cycle of the seasons, which in most pre-modern societies was an extremely powerful determinant of human lives. Together they fostered a similarly cyclic or “steady-state” view of human cultures, of the Earth, and of the universe as a whole. Against this background, the idea that the world has had a unique starting point and a linear and irreversibly directional history—an idea that first emerged in Judaism and was extended in Christianity (and later in Islam too)—stands out as a striking anomaly. Each of the Abrahamic faiths condensed its directional view of history into an annual cycle of fasts and festivals (Passover, Easter, etc.), which replicated the cosmic picture in miniature on the more accessible scale of ordinary human lives. But the larger-scale picture remained paramount, namely that humanity, the Earth, and the universe have jointly had a true history, with an irreversible arrow-like direction to it.

This strong sense of history gave the Judeo-Christian tradition an underlying structure that is closely analogous to the modern view of the Earth’s deep history (and cosmic history) as similarly finite and directional. More specifically, the science of scholarly chronology, as a way of plotting human history with quantitative accuracy and of dividing it into a qualitatively significant sequence of eras and periods, was closely analogous to the modern science of “geochronology,” which tries to give a similar kind of precision and structure to the Earth’s deep history, dividing it in the same way into eras and periods. Whether these are “mere” analogies, or something much more, is a question that the rest of this book will explore.

To summarize: the history of the universe, the Earth, and human life itself was traditionally conceived in the West as having been very brief in comparison with the modern picture. But this is a relatively trivial difference: the quantitative contrast is less significant than the qualitative similarity. What is not trivial is that the scholarly history represented by chronologists such as Ussher was almost exclusively based on textual evidence (the astronomical evidence of past eclipses, comets, etc. also came from textual records). Even in the historical analysis of Noah’s Flood by scholars such as Kircher the textual evidence was dominant and the use of natural evidence was marginal.

At much the same time, however, and still in the 17th century, other scholars were beginning to bring the natural evidence much more substantially into debates about the Earth’s own history, yet without seeing any obvious need to extend the timescale on which it had played out. This is the subject of the next chapter.

Excerpted from “Earth's Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It Matters” by Martin J. S. Rudwick. Copyright © 2014 by Martin J. S. Rudwick. Reprinted by arrangement with University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.

Shares