Responding to the awful news of terrorist assassinations in Paris last week, President Obama recently reminded us that France was our “oldest ally” and that “time and again, the French people have stood up for the universal values that generations of our people have defended.”

France came to America’s rescue at its birth in 1778, but the truth is that many among the aristocratic ruling class lived to rue that day, for they blamed the example the American republic had set for the French Revolution of 1789. Distrust of Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité still lingered in the French mind when America faced its own revolution in 1861, and many were glad to interpret this as further proof that democracy always ended in anarchy and violence. Emperor Napoleon III welcomed America’s war as an opportunity to seize Mexico and restore the American branch of the “Latin race” to order under a European monarch. Though he stayed neutral, he secretly wished for an independent Confederacy to shield Mexico from U.S. interference in his Grand Design for Mexico.

But what of the French people? Where did they stand on America’s war with itself? John Bigelow, a veteran New York newspaperman and savvy political operator, was sent to Paris in 1861 as U.S. consul, but his unofficial mission was to “manage the press.” Bigelow realized it would never work to try educating the French as to what to think about America. Instead, he enlisted French journalists, intellectuals and opposition political leaders who saw in la question amércaine an opportunity to reopen forbidden political debate. Under the Second Empire basic freedoms of expression and assembly were censored; even singing "La Marseillaise," the French republican anthem, was banned. The opposition met in Masonic lodges, lecture halls, cafes and private dinner parties.

When the Civil War came to an end in April 1865 Bigelow found himself appointed as U.S. ambassador to France. His predecessor, a New Jersey politician named William Dayton, had dropped dead of a stroke in the apartment of an American woman described as an “adventuress.” When the awful news of Lincoln’s assassination arrived in Paris late that April, Bigelow was amazed to see Parisians of all ranks pouring into the streets to share their shock and grief. Two nights later thousands of students gathered in the Latin Quarter in defiance of Napoleon III’s ban on political demonstrations. With swords drawn police rushed the crowd and made arrests, but squads of students broke away and made their way through the back streets to arrive, sweaty and exhausted, at Bigelow’s private residence some three miles away. They broke through a police cordon barricading Bigelow’s front door. Once inside the astonished diplomat’s home, one student stepped forward and read a prepared statement. It expressed their sympathy for the death of President Lincoln and their solidarity with the Great Republic of America. Vive Lincoln! they shouted. Vive Grande République américaine!

“I had no idea that Mr. Lincoln had such a hold upon the heart of the young gentlemen of France,” he wrote to Washington. No one had any idea until that terrible April in 1865.

Not long after that night, a group of eminent French liberals gathered for dinner at the country home of Édouard Laboulaye, a professor of history and law who had been among Bigelow’s most valuable assets in the Union’s campaign to win public sympathy in France. Among them was Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, a young artist from Alsace, who later recalled that after dinner Professor Laboulaye first raised the notion of some kind of monument to liberty.

The idea for the monument did not come to life until a few years later, after Napoleon III was toppled from his throne during France’s disastrous war with Prussia, and after the republican experiment was resumed in its French birthplace. Laboulaye and his fellow liberals sent Bartholdi to the United States to solicit American cooperation and he arrived in New York in June 1871 enthralled by the idea of a colossal allegorical figure that would stand at the gateway to the New World.

It took 15 years to raise the money and complete the project. Bartholdi had difficulty raising money among New Yorkers, who saw no practical value in this Frenchman’s dream and were none too keen on celebrating radical French ideas. Nor had they forgotten France’s flirtation with the Confederacy, and many had taken sides with the Prussia in the recent war.

Back in France, Laboulaye found French donors still terrified by the kind of revolutionary republicanism that had erupted with the Paris Commune in 1871; some yearned for a return to monarchy. Even republicans were skeptical about America’s vulgar republic as a model for France. “She is not liberty with a red cap on her head and a pike in her hand, stepping over corpses,” Laboulaye assured them. Liberty “in one hand holds the torch—no, not the torch that sets afire but the flambeau, the candle-flame that enlightens,” he explained. And in her other hand, “she holds the tablets of law,” the symbol of authority and order.

In 1875 Laboulaye formed the Franco-American Union with such illustrious names as Hippolyte de Tocqueville and Oscar de Lafayette, grandson of the American revolutionary hero, to raise 400,000 French francs for the statue he had christened La Liberté éclairant le monde (Liberty enlightening the world). They held gala events, including a banquet at the Louvre and a soirée musicale at the Palais Garnier opera house, and publicized the campaign as something that would unify moderate monarchists and republicans.

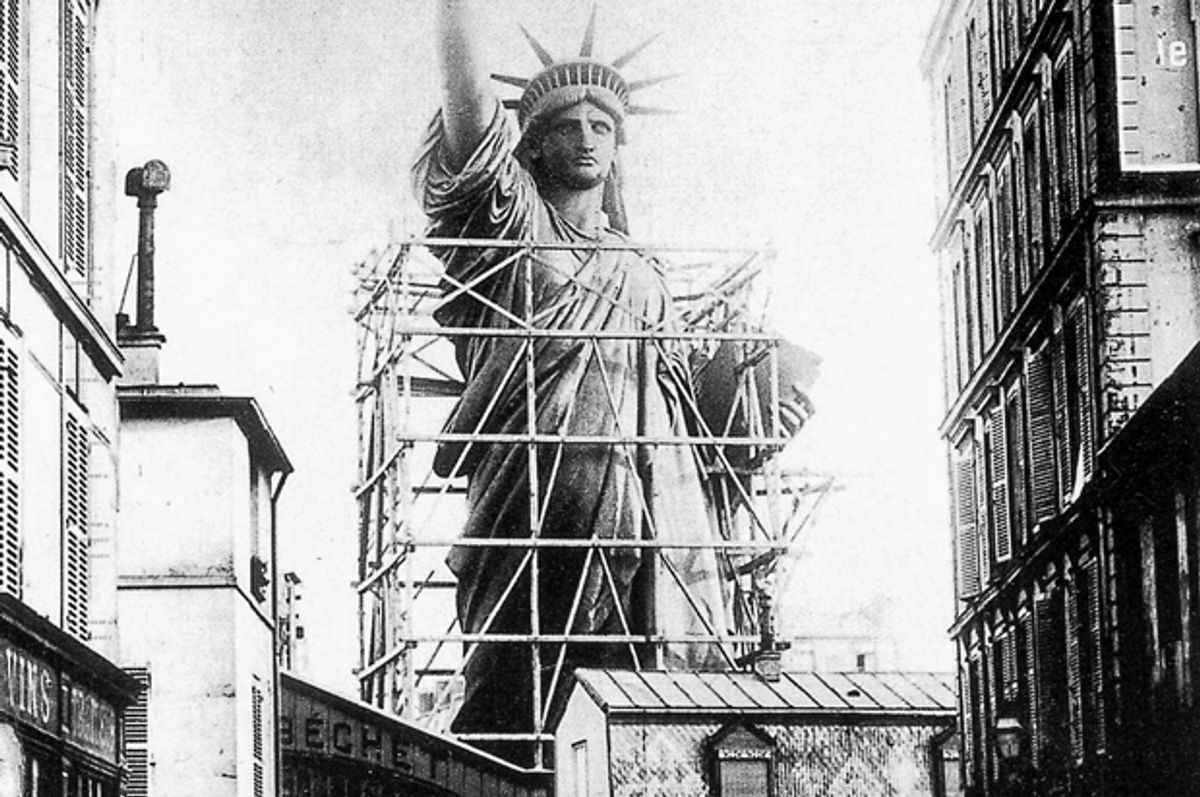

As the money trickled in, Bartholdi began work on the statue, and by 1876 he was able to send the arm holding the flambeau and the crowned head to Philadelphia for the Centennial Exposition. Soon Liberty, encased in scaffolding, could be seen towering above the streets of Paris near Bartholdi’s atelier on the northwest edge of the city.

By the time it was installed in New York Harbor in 1886, Americans were trying to put aside, if not forget, the Civil War and the legacy of slavery. Emma Lazarus’ moving poem “The New Colossus” redefined the monument as America’s welcome to the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” escaping Old World despotism. The Statue of Liberty, as it would be known, became a symbol of America as a sanctuary for refugees from the world, rather than Liberty enlightening the world, and as a national icon it would play a central role in the narrative of exceptionalism that Americans would tell themselves about themselves.

But Bartholdi, Laboulaye and the French republicans had something else in mind with this monument, something worth remembering in these times of terror. With her gaze fixed across the Atlantic, Liberty strides toward Europe across the sea, the broken chains of slavery at her feet, the rays from her crown radiating to the seven continents of the world. In one hand she holds a tablet marked “July 4, 1776,” and in the other the raised flambeau “radiant upon the two worlds,” as Bartholdi put it. Liberty Enlightening the World is the greatest monument to America’s Civil War and to the enduring bond between the French and American peoples. Above all, it is a monument to the international fraternity among those willing to defend the ideals of liberty and equality, and as such its spirit yet looms over Paris today.

Don H. Doyle, author of "The Cause of All Nations: An International History of the American Civil War" (Basic Books, 2015), is McCausland Professor of History at the University of South Carolina.

Shares