"We know we need to do something about students who are not achieving in our schools."

That anxious appeal – along with its many variations – has become the refrain now firmly embedded in speeches and opinion columns about American public education.

Yes! Do something. About those kids.

Only this time, the anxious appeal is coming from Jai Sanders, an African-American parent in Nashville, Tennessee, who has a stake in the matter: The something about to be done is aimed squarely at him and his children.

Sanders, pausing briefly before assembling a bagel with lox and cream cheese, explains, "But what we're currently doing is throwing solutions at the wall to see what sticks, without any research or any consultation with the people who are affected the most."

His tone of voice doesn't carry a trace of the anger or resentment that could be inferred from what he just said. Actually, Sanders exudes affability. With a green ball cap tipped slightly back from his cherubic face, he gestures broadly and smiles incessantly. His impossibly well-behaved 3-year-old daughter seated beside him only occasionally diverts him as she carefully navigates her bagel.

They live with mom and the rest of the family in the same house where Jai grew up – the third generation of Sanders to live in their home in East Nashville.

Sanders, who attended both public and private schools while growing up in East Nashville, has chosen, along with his wife, to send their children to their neighborhood public school, Inglewood Elementary. Inglewood was "the default for us," he says.

An older daughter who attends the school has been identified gifted and talented which has enabled her to be included in a program where she is provided with an Individual Education Plan so she receives specific attention to her abilities.

Yet now Sanders finds himself and his family swept into a raging Music City controversy. Conversations about public education – where you send your kid to school, where other parents send their kids, and who gets to decide – have exploded into acrimonious bickering, full of charges and counter-charges.

The debate pits parents against parents, schools against schools, and communities against communities. School board meetings have turned into raucous events that sometimes descend into boisterous demonstrations. And public officials swipe at each other in social media and opinion columns, accusing one another of having ulterior motives.

"None of this was in the "dad manual" when I started a family," Sanders explains, making quote marks in the air. "I'd much rather go back to being a PTO dad planning the Christmas party rather than going to meetings and shouting my head off to save our school."

"We love Inglewood Elementary," Sanders says, although he admits, "not all parents agree with me."

Apparently, neither does the state of Tennessee.

We've Made Your School a "Priority"

As state media outlet The Tennessean reported recently, low scores on student standardized tests and other indicators led the state to designate 15 Metro Nashville Public Schools, including Inglewood, as "Priority Schools."

"Priority Schools are the lowest-performing 5 percent of schools in Tennessee," according to the state's education department, making them "eligible for inclusion in the Achievement School District or in district Innovation Zones. They may also plan and adopt turnaround models for school improvement."

The plain English translation of that benign bureaucratic speak is that Inglewood has been labeled a failure by the state, which gives the state or district power to do something to it. Often, the something that gets done to a Priority School in Tennessee is to fire the school's principal or teachers, hand the school over to a charter school management organization, or a mixture of the above.

One of the potential options the district has chosen for Inglewood is for the school to be taken over by the KIPP nationwide charter school management organization. The outgoing district superintendent, Jesse Register, has already disclosed the district has signed a contract with KIPP, only he won't say which school KIPP is destined to take over.

Sanders is not the only Nashville parent dreading the fate that could befall a local school.

"Not In Favor Of Chaos"

Across town, Ruth Stewart shares a similar perspective about the fate of a different Nashville elementary school.

Like Inglewood, Kirkpatrick Elementary has also been designated a Priority School and potentially targeted for a charter takeover. Superintendent Register has promised to announce soon which of the two schools – Inglewood or Kirkpatrick – will be turned over first.

Also like Inglewood, Kirkpatrick serves a disproportionate percentage of children from low-income African-American and Hispanic households. Although Stewart does not have a child attending Kirkpatrick, she speaks admiringly of its teachers, describing how they "take on the duties of social workers – make sure kids get home okay, make sure they have warm coats to wear in the winter."

Stewart, who is white but has an adopted African-American child, says, "Kids at Kirkpatrick don't get the privileges my kids have gotten. So why aren't we divvying up resources equitably to help solve that?"

At a lunch spot in West Nashville known for serving healthful fare, she speaks about her situation in Metro Nashville Public Schools. Between forkfuls of a salad of chicken and mixed greens she describes the "chaotic" situation in Nashville, contrasting it often to what she is familiar with in the practice of medicine. She is a physician.

"Nothing has been transparent about the current agenda. This sows anxiety and division in the community," she says.

Stewart sees the consequences of new education policies in Tennessee as having a "negative impact on people's feelings that schools are part of the community … I'm not sure what to do, but I'm not in favor of chaos."

Nashville has two middle schools facing a similar fate. The two schools, Neely’s Bend Middle Prep and Madison Middle Prep, have both been placed on the state's Priority list, removed from the oversight of the Nashville district, and grouped with other troubled Tennessee schools in the state's Achievement School District.

The ASD was founded as part of Tennessee's effort to qualify for the Obama administration’s Race to the Top grant.

What state takeover means to the students, parents and teachers of Neely’s Bend and Madison is that one of their schools – again, to be announced at a later date – will be handed over to a charter management operation.

Because the ASD is a charter authorizer, it can designate any of its schools for charter takeover, and indeed has done so numerous times. In fact, the superintendent of the ASD, Chris Barbic, is the founder and ex-CEO of the Yes Prep chain of charter schools. When the ASD rolled into Memphis, another troubled Tennessee school district, the ASD immediately began targeting the district's schools for takeover by charter operations, as a 2013 report from The Atlantic recounted.

Enforced charter takeovers like the ones being carried out in Tennessee are happening across the country.

We're All Nashville Now

The debate in Nashville echoes themes the nation has heard from New York City and Los Angeles where students, teachers and parents have engaged in prolonged battles over decisions to co-locate charter schools in public school buildings.

In Newark, New Jersey, a state-imposed plan enacted this year intends to move charter schools into the district's facilities. In Detroit, the state agency in charge of that city's schools has a new plan to convert over 30 percent of the districts into charter schools. In Wisconsin, a bill has been introduced in the state legislature that would make all public schools deemed to be "failures" become charter schools.

Most recently, the school district of York, Pennsylvania, made national headlines when the state announced the city's schools would be turned into an "all charter" district. As a report at The Daily Caller explained, a legal path has been cleared for a state "recovery officer" to proceed with "a plan to place all of the city’s public schools under the control of Charter Schools USA, a for-profit school management company."

The idea of an "all charter" school district has been tried before, in Muskegon Heights, Michigan. The results were disastrous as the charter operator promptly alienated most of the teachers and then backed out of the deal. But that seems to deter no one directing these efforts.

In every one of these charter takeover cases, there have been large numbers of students, parents and teachers who have spoken out in opposition.

And although takeovers of "failed" schools are often justified as rational responses to "urban decay" or "underutilization," none of these arguments apply to Nashville. Nashville is a city that is experiencing strong growth in population and employment, and public schools are experiencing problems with overcrowding because of high demand for their services. Nashville is a neither a union bastion nor a hardened, bitter battleground of Big City politics. So it's not hard to imagine that if a fight like this can break out here, it could break out anywhere.

What policy leaders and charter advocates contend, in nearly every one of these takeover cases, is that they are following the reform model from Louisiana's state-operated Recovery School District, which took over most of New Orleans' public schools after Hurricane Katrina.

Thing is, there hasn't been another Katrina. Instead, there's been a manmade disaster.

Due to the influence of federal policies, such as Race to the Top, and relentless marketing by charter school advocates, virtually every state has a methodology for designating "low performing" schools as Priority and targeting them for radical solutions like charter school takeover.

Accountability Gone Awry

Back when these plans for targeting the nation's "low performing" schools were unveiled by the Obama administration, the National Center for Education Policy, an education policy research think tank affiliated with the University of Colorado, Boulder, warned in a brief that the Obama plans's accountability system, "which determines how schools will be evaluated" is not substantiated by any legitimate research, and that the "intervention models for low-scoring schools is not developed, much less supported in the research."

Indeed, the notion that education performance of public schools can be turned around by taking them over and converting them to charter schools or co-locating charters in their buildings is particularly unproven.

Even in New Orleans, mass charter conversion has been "disastrous," writes Kristen Buras for The Progressive. After the charter takeover of NOLA public schools post Katrina, the state began issuing letter grades for all schools in 2011, and 79 percent of charter schools in the New Orleans district received a “D” or “F.” In 2014, RSD-New Orleans schools are still performing below the vast majority of the state’s other districts at the fourth and eighth grades in subjects tested by the Louisiana Educational Assessment Program, including English language arts, math and science.

In Tennessee, state takeovers of public schools have so far yielded mostly disappointing results too, according to math teacher and statistical whiz Gary Rubenstein. "They are still in the bottom 5 percent, dead last with the second to last district not even close to them," he writes.

Despite these troubling results, there are powerful advocates for continuing charter takeovers of public schools. Takeovers and other methods of proliferating charters, such as vouchers, have helped push the number of charter schools in America over the 6,400 mark in 2013-14, with more than 2.5 million students enrolled, according to The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. Charters are now the fastest growing segment of our public education system.

Doing the Math

In Nashville, charter school performance varies widely, with some performing significantly better than the rest of the state and better than Nashville public schools, while others are at the bottom of state rankings.

But academic performance doesn't seem to be the most important factor in selecting which schools are targeted for charter takeover and which are not, at least not in Nashville. As Nashville school board members Amy Frogge and Jill Speering point out in a recent op ed, one of the middle schools targeted for state takeover, Neely's Bend, performs better on state assessments than many other Nashville schools do – and better than schools already taken over by the state.

Also, charter schools may pose a drain on public school finances. According to a recent study conducted by the Florida-based research firm MGT of America, growth of charters will harm Nashville public schools overall. "The loss of even a single student will reduce the revenue received," the report states, because "the reduction of a single student in a classroom will not alleviate the need to have a teacher in that classroom … In fact, the per-pupil cost for that classroom or school would increase because the fixed expenses would remain, but the revenue to support them would be decreased."

The report estimates that the net negative fiscal impact of charter school growth on the district's public schools would be more than $300 million in direct costs over a five-year period. This figure is likely an under-estimate, the report contends, as there are "other indirect costs" of charter schools related to administration that are "not easily identified." Meanwhile, there are no new revenue sources being considered to offset the additional costs. "There appears to be an assumption," the report notes, "that the central organizations supporting the charter schools can continue to do so within existing resources."

The MGT report is mostly supportive of the idea of charters and recommends ways to ensure their success without harming public schools. Nevertheless, it concludes, "New charter schools will, with nearly 100 percent certainty, have a negative fiscal impact" on the school district." (emphasis added)

When It's Your Kid

The numbers arguments don't even begin to capture what's driving a lot of parent anxiety in Nashville.

"I'm not anti-charter," Jai Sanders declares. "I don't advocate closing any East Nashville charters." But he does have specific reservations about turning Inglewood into a KIPP charter school.

He strongly objects to the heavy handed, top-down way Nashville Metro school leaders have gone about the process of pushing charter governance on neighborhood schools. For instance, he is worried about the principal of his child's school, who he is happy with, being forced out.

Sanders says the district has enough charter schools as it is. "Charter schools should be something on the periphery. They were originally supposed to be incubators of ideas and not the standard for schools in the community."

Sanders also has "philosophical problems" with the way some charter schools "go about their business," specifically how they are governed by boards of directors rather than school boards. "This way of doing education doesn't seem like education to me."

Sanders mentions KIPP charter schools in particular, as a model of education he has "reservations" about. KIPP is known for practicing an approach to schooling loosely labeled as "No Excuse," which relies on strict behavioral controls of students. He describes KIPP's approach as a "military school for civilians, with the extreme tracking of students, requiring SLANT, and no excuses." SLANT is a foundational practice in KIPP schools that dictates students must Sit up, Listen, Ask and answer questions, Nod and Track the teachers' movements. There have been numerous, verified reports of KIPP and other charter schools practicing the No Excuse approach, using very harsh disciplinary practices, including high rates of suspensions and expulsions, on students.

Ruth Stewart – who describes herself as "anti-charter" but "willing to work with my pro-charter colleagues to have an outcome we all can live with" – also expresses reservations with the charter school she visited, Liberty Collegiate Academy in the RePublic School charter chain. "Not for my kid," she states. "It was very tightly controlled … eye contact, hand clapping, too controlling."

She contrasts the "controlling" environment of No Excuse charter schools to what she has observed in public schools, where she has experienced "a much more nurturing learning environment."

"I understand some parents would choose KIPP and the No Excuse approach," she says. "But something leaves me very uneasy about that kind of control exerted on children of color. So all white kids get to go to a school with a Montessori approach while children of color get eye control?

"What we all want are children who are autonomous, responsible and intrinsically motivated. But I'm not sure these types of charter schools get us where we want to go."

[Editorial note: A pro-charter Nashville parent contacted for this article declined to be quoted on record.]

Another oft-stated reservation with charter schools is their unquestionable link to increased segregation of students based on race and income.

"Studies in a number of different states and school districts in the U.S. show that charter schools often lead to increased school segregation," writes Iris C. Rotberg, a research professor of education policy at The George Washington University’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development, in Education Week.

"Even schools that employ a seemingly randomized under lottery system for enrolling students," Rotberg explains, "also choose – sometimes explicitly and sometimes indirectly – and increase the probability of segregation. They limit the services they provide, thereby excluding certain students, or offer programs that appeal only to a limited group of families."

Rotberg cites studies showing, "In some communities, charter schools have a higher concentration of minority students than traditional public schools," while "In others, charter schools serve as a vehicle for 'white flight.' … School segregation increases in both cases."

Some Nashville parents also feel charter school proliferation has led to increased racial segregation of students. "A lot of charter school rationale is based on racial diversity, but it seems to me we're getting less diverse due to charters," Stewart states.

Stewart's observations may or not be accurate. That would require statistical analysis. But parent perceptions are often stronger influencers of public opinion than statistics.

Charter school advocates understand that all too well.

Evolution of a Movement that Is "Bad for Kids"

Indeed, the rhetoric driving charter school advocacy has changed dramatically over the years as proponents of charter schools condition public perceptions to accept the expansion of these schools.

That evolution has been documented extensively in the recently published book "A Smarter Charter: Finding What Works for Charter Schools and Public Education," by Richard D. Kahlenberg and Halley Potter.

The original vision of charter schools, the book contends, was to provide "laboratory schools" to "experiment" with different approaches that could eventually be considered for adopting on a much larger scale. Two foundational tenets to these experimental schools, the authors maintain, were for teachers to have a stronger voice in determining the management of the school and for the student body to have higher degrees of economic and racial diversity than traditional public schools.

However, as states began enacting legislation to create and spread charter schools – beginning with Minnesota in 1991, then ramping up significantly under the presidential administration of Bill Clinton – there was a "more conservative vision" repeated again and again that reinforced charter schools as "competitors" to the public school system – even to the extent of replacing public schools, some argued.

"The public policy rhetoric changed from an emphasis on how charters could best serve as laboratory partners to public schools to whether charters as a group are 'better' or 'worse,'" the book argues. And "over time, the market metaphor came to replace the laboratory metaphor."

Desires to break public school teachers' unions crept into arguments for the spread of charters as well, as "conservative charter school advocates argued that having a nonunion environment was a key advantage – perhaps the defining advantage – over regular public schools," and influential voices in public school policy, such as former Assistant Secretary of Education Chester Finn, who had been initially skeptical of charter schools, gradually became strong advocates for creating more of them.

"Rather than emphasizing diversity and the possibility for breaking down segregation," the authors argue, "charter school supporters began advocating for schools to target minority and low-income group members who are demonstrably in need of better schools." The need to target these student populations has been rationalized by rhetoric to "prioritize" these students and spread the notion they need "a different set of pedagogical approaches," such as the No Excuse approach.

The authors cite numerous examples of charter schools – mostly individual charters rather than the charter school chains providing so much growth of the sector – that adhere more so to the original vision of charters. None are in Tennessee.

The authors conclude, "The current thrust of the charter school sector … is bad for kids." They recommend "changes to federal, state, and local policy" and a greater degree of "neighborhood partnerships" among charters, public schools, foundations and universities if these schools are to "be a powerful vision for educational innovation in a new century."

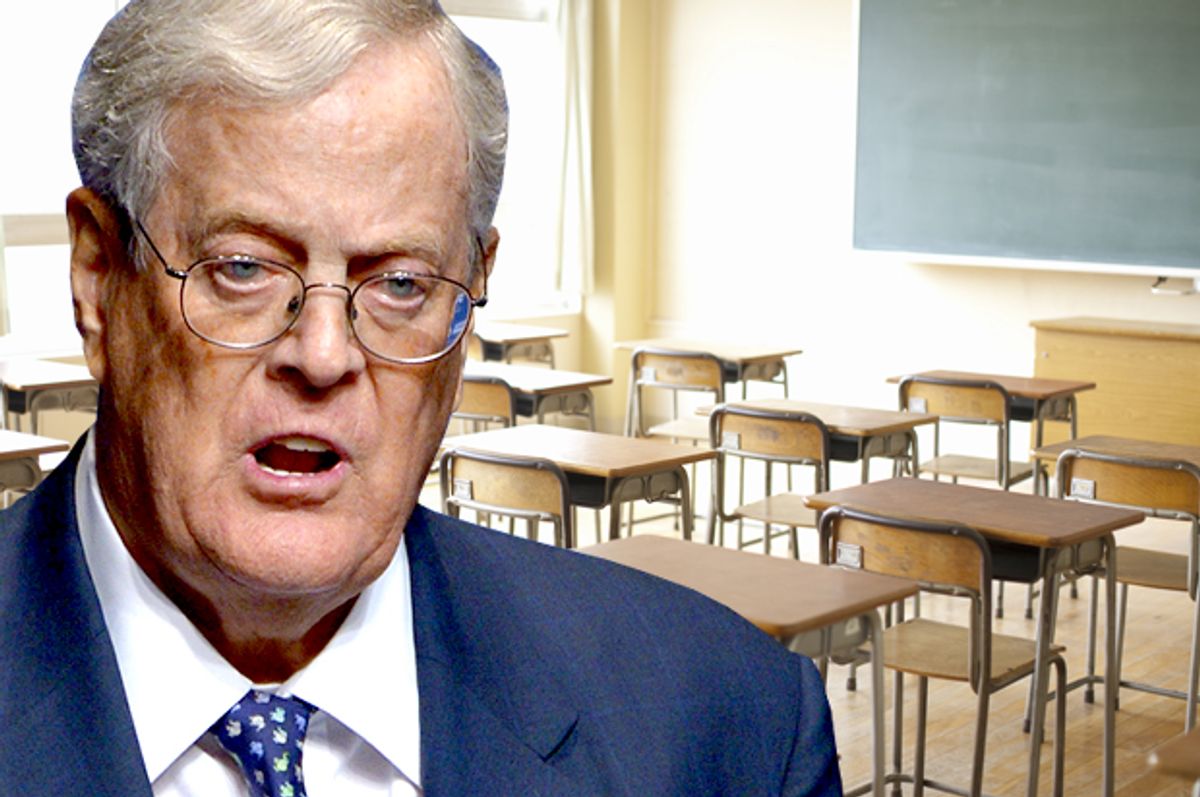

Enter the Koch Brothers

For sure, charter schools have become a darling of conservative politicians, think tanks and advocates.

One of those powerful advocates, nationally and in Tennessee, is the influential Americans for Prosperity, the right-wing issue group started and funded by the billionaire Charles and David Koch brothers.

AFP state chapters have a history of advocating for charter schools, conducting petition campaigns and buying radio ads targeting state lawmakers to enact legislation that would increase the number of charter schools. In an AFP-sponsored policy paper from 2013, "A Nation Still at Risk: The Continuing Crisis of American Education and Its State Solution," author Casey Given states: "The charter school movement has undoubtedly been the most successful education reform since the publication of A Nation at Risk.," the Reagan-era document commonly cited as originating a "reform" argument that has dominated education policy discussion for over 30 years.

The Koch brothers themselves have been especially interested in public policy affairs in Tennessee generally and Nashville in particular. "Tennessee is a political test tube for the Koch brothers, " the editors of The Tennessean news outlet write in a recent editorial. The editors cite as evidence the influence AFP had recently in convincing the Tennessee legislature to block a bus rapid transit system project in Nashville.

In July of last year, the Charles Koch Institute held an event in Nashville, "Education Opportunities: A Path Forward for Students in Tennessee," to provide an "in-depth policy discussion" about public education and other issues.

As The Tennessean reported, the forum was advertised as "a panel talk with representatives of charter schools and conservative think tanks," including outspoken and controversial charter school promoter Dr. Steve Perry.

Although the emphasis apparently was mostly on school vouchers, according to a different report in The Tennessean, the stage was thick with charter school advocates from Indianapolis-based Friedman Foundation for Education Choice, the Arizona-based Goldwater Institute and Nashville's Beacon Center of Tennessee.

The reporter quotes Nashville parent T.C. Weber, "who questioned the 'end game' of diverting funding from public schools" and said, "'Are you looking to destroy the public system that we already have and build a new one based on your ideas?'"

Weber writes about the event on his personal blogsite: "One of the questions asked of the panelists was what do [you] feel is the biggest obstacle … to the accepting of your vision. The reply was, 'educating parents.'”

The presence of influential conservatives from outside the city "educating" Nashville parents about what kind of schools their children need has created resentment and suspicion in many Nashville citizens' minds. Many fear the drive to expand charters is powered more by powerful interests outside the city than by the desires of Nashville parents and citizens.

We've Been 'Hijacked'

One of those suspicious Nashville parents is Will Pinkston. Pinkston, who serves on the Metro Nashville Public School board, tells a compelling narrative about good intentions gone awry and the actors who have rushed into the wreckage to exploit what they could.

Pinkston graduated from Nashville public schools and currently has a daughter attending one of those schools. Between 2003 and 2010, he was a state employee very much connected to the school policies being implemented in Nashville today.

As a staffer in the administration of former Tennessee governor Phil Bredesen, Pinkston was instrumental in devising the state's successful proposal to receive money from the Obama administration's Race to the Top competitive grant program. Tennessee was one of the earliest recipients of the grant money and has long been considered a model for other states to emulate in their reform efforts.

But what Pinkston sees playing out in Nashville is not very much to his liking. "I can say with a great deal of certainty that what has happened is not what was intended when we created Race to the Top."

"We wanted scalable solutions for every school," Pinkston recalls in a phone interview. "But the charter school movement has hijacked education policy."

In hindsight, Pinkston now sees that RTTT and its other reforms spawned a lot of bad thinking about education.

"Now we have an 'irrational exuberance' for reform," Pinkston contends, using the term Alan Greenspan coined for describing the economic speculation in the country that led to the stock market run-up in the 1990s.

According to Pinkston, the reform frenzy brought on in part by RTTT also brought into Tennessee "a lot of radical reformers who believed, 'This is our time.'"

He is particularly critical of the state ASD, which he thinks has strayed from its original purpose. "I believe in the concept of the ASD. It causes districts to reach and stretch," he says. The ASD was a "product of RTTT," according to Pinkston. "I helped coin the name of it," he claims.

However, the initial intention, according to Pinkston, was to target a small number of schools that needed the most attention and to conduct a temporary leadership change in those schools, "not to occupy them in perpetuity."

What changed that, Pinkston contends, was when state superintendent Kevin Huffman and the ASD leader Chris Barbic turned the agency into a charter authorizer. "That's not turning around a school. That's turning your back on it," he states.

Pinkston also points to the Tennessee Charter School Center as among the actors, along with the Nashville mayor, who are working to "charterize the system."

There's little doubt that TCSC has clout. Last year, the group had eight lobbyists working the Tennessee state legislature to pass a new law allowing charter schools denied locally to get approval instead by the Tennessee State Board of Education. The law passed. For this and other reasons, Pinkston has called the charter school group "a threat to public education in Nashville" in a lengthy email to his fellow Metro council members.

Pinkston contends that education policy leaders in Tennessee had originally articulated a set of priorities for charters, a narrative very much similar to what the book "A Smarter Charter" relates at the national scale. The intention was to responsibly manage the growth of these schools, tap any innovative strategies they may have, take advantage of a glut of abandoned commercial property in parts of town that are underserved educationally, and, yes, convert some low performing schools. "In some places where schools have descended into the bottom 5 percent," he explains, "we've lost our moral authority, making it proper to reach out to the expertise charters may have."

Now, what's happening to Inglewood Elementary and other Nashville schools, Pinkston says, charter conversions are being conducted like a "shotgun wedding."

"Our job is not to engineer hostile takeovers … It's immoral to force this kind of change on people who don't want it. It also diminishes the odds of success."

The Other Side

Pinkston is a minority voice on the MNPS board.

Fellow board member Mary Pierce, also a parent with children in the Metro system, is likely more representative of the state of school governance currently in Nashville.

In a phone interview, she contends what's happening in Nashville is not a sudden takeover of the local schools by any kind of "movement." She maintains that problems in the public schools have been going on for decades and is unconvinced by those who say charter schools are "the problem." She bases a lot of her opinions on her experiences tracking numerous students from public schools in her volunteer tutoring, along with her husband, of high-needs students and her conversations with other parents in the system.

"What we're having are a lot of conspiracy theory arguments for why charter students perform better," she contends. "We're hearing public schools just need more money and that current new trend for wrap-around services. We have people making accusations that charters are just out to make money … We can't seem to get past that money issue to have a reasonable conversation and allow charters to be one of our options."

Pierce speaks with the fervency of someone who definitely wants to do something about the low academic achievement of Nashville students. "When you have elementary kids two and three levels behind, they usually don't catch up," she says, a point hardly anyone would dispute.

She claims to be agnostic about whether the school is a charter or public. "As long as the school can get students to perform better … I'm not hung up on the designation of what type of a school it is. We have to throw away these stereotypes."

"For the city to move forward we have to keep the conversation rooted in fact, and that's not being done," she says. The "facts" Pierce tends to prefer are test scores, although she acknowledges, "My kids have always done well on tests. I don't put everything into a test score."

However, in Pierce's view, student scores on standardized tests, particularly math tests, are a "litmus test" of the school's overall quality. "If the school is doing the job it's supposed to be doing, then the test scores will follow."

Does that mean when schools have low scores on standardized tests, one can conclude teachers in that school aren't doing the job they're supposed to be doing? "When schools aren't performing well, there has to be an evaluation done?" Haven't these schools been evaluated? "An evaluation was done but the schools are still getting left behind," she feels.

"The only place I've seen these kids improve is in charter schools," Pierce says. When pressed to elaborate on her tough assessment of public schools, she recalls one exception – a public school principal who obtained money from a private source to fund an intensive math-tutoring program. But that program ended due to lack of continued funding.

View from the Educators' Eyes

Such a negative view of public school educators is really hard to reconcile with what you experience when you actually meet these people.

Isaac Litton Middle School principal Tracy Bruno is one of those educators who seems incredibly devoted to his job. In a school walkthrough conducted with staff members from the National Education Association, Bruno says, "Our parents know if you email me on nights, on weekends, I'll email you back," admitting in the next breath how this sometimes "gets me into trouble with my wife."

Years of spending hours of nearly every day within the same building as scores of children have given him a prudent way of speaking and a humble demeanor. After hearing him explain the care and seriousness he has for his school and its children, it's impossible to imagine looking him in the eye and saying, "You know what, you're really lousy at your job."

Inglewood is one of the elementary schools feeding into Isaac Litton Middle School in Nashville. So principal Bruno inherits any problems created by the "failing school." Yet when Bruno is asked about his preference for what should happen to Inglewood, charter takeover is nowhere near the top of his list.

Bruno describes Inglewood as the "have-not" of feeder schools for Litton in comparison to another elementary school, Dan Mills, whose generally more well-to-do students also often matriculate to Litton. (Through Nashville's choice program, Litton also attracts students from "out of zone.")

To illustrate what he means by "have-not," he describes visiting some of the homes his students come from. "I've been in homes that are totally dark so the family can save money on electricity … or homes where they use the oven for heat. We have kids who sometimes don't have a way home from school."

But Bruno does not regret that students with low test scores from Inglewood flow into his school, despite how it might affect student test scores for Litton. He considers the diversity of the student body a strength and credits the presence of Inglewood students as the reason Litton's diversity is maintained. His appreciation for the presence of Inglewood students extends into student programs, as evidenced by a corps of Litton students who volunteer every semester to spend time with Inglewood fourth graders helping them learn how to read.

"This doesn't mean we have low expectations for students," Bruno states, and he is quick to tout the school's discipline, academic and citizenship expectations embraced under his leadership. Nevertheless, he balances his high expectations with a need to "meet the kids where they are."

When asked how he would contrast his approach to a No Excuse model such as KIPP, he states, "I don't choose to implement that model. Given the kind of diversity we have, we have to be more differentiated in our approach. You really don't have to run a school like a military structure to have a safe and orderly school."

Inglewood second grade teacher Suzan Rider is another of those public school educators whose dedication seems unquestionable.

Her classroom is bright and colorful. The children are captivated with her lesson – this one about past tense verbs. At each student's place, there are strips of paper with common verbs to match to paper strips with past tense endings. As an animated Rider gestures from the middle of the room, calling out the words one at a time, the students dutifully follow along, matching the strips. When Rider asks a question, hands fly up to answer. A correct answer prompts Rider to make a squirting gesture toward the child with the exclamation "FAN-" followed by a wiping gesture "TASTIC," and the kid just beams.

"Very frustrating," is how Rider describes the way Inglewood has been targeted for possible charter takeover. Rider, who has been teaching for over 30 years, chooses to teach at Inglewood precisely because of the challenging nature of the school. "We know these students have it rough," she states, referring to problems associated with the socio-economic standing of the students that often include very low household incomes, emotional trauma, uneducated parents and neglect at home due to parents working multiple jobs. "Many of us have had to occasionally walk a child home from school to make sure they got there okay," she explains. "But teachers are at Inglewood because they choose to be here."

What particularly exasperates Rider is that despite what teachers do at Inglewood – "We're doing everything within our power," she declares – the school would be judged a failure by a process that seems completely remote and disconnected fom the school. "How can someone make a decision about our school when they haven't even been in our school?" she asks.

Of course advocates for charter schools and other alternatives to public education are quick to say how much they revere teachers and principals too. It's the structure of public school that is the problem, they contend – the old, "It's not the people, it's the system" argument.

But as you walk around the halls of Inglewood Elementary – a school where technology is bare-bones (teachers don't even have Smartboards) and classroom materials are all obviously painstakingly hand-crafted by the teachers themselves (doubtlessly with their own money) – it's really hard to see this small, beleaguered building as "the system," when it feels a whole lot more like it is a victim of the system.

This Could All Be Different

So what's to be done to "failed" schools like Inglewood and Kirkpatrick elementary schools and Neely's Bend and Madison middle schools? What is the something that will right their trajectory?

Regarding the fate of Inglewood Elementary, Pierce says, "In the past three years only 15 percent of students are performing on grade level. I'm not saying that going charter is the only solution. But something must be done about it. Something needs to happen."

According to Pinkston, converting a bottom-performing public school doesn't seem to apply to Inglewood. "Schools like Inglewood have been systematically and deliberately starved. We should not have failed this school in the first place. We need instead to focus on providing the structured support these schools need."

Pinkston would prefer the focus be on what he contends is "the real problem … lack of state funding."

"We have a lot of big problems," Pinkston understands, citing among them a challenging growth in the percentage of students who are not native English speakers and high student attrition in the middle grades.

"But instead of proven solutions we've got unfounded ideas like charter schools."

"My solution," Ruth Stewart offers, "would not be to take Kirkpatrick away and make it a charter. What charter advocates appear to support is to make Kirkpatrick a charter despite what parents want. What Kirkpatrick advocates want is not the 'status quo.' They're questioning why some resources – for instance, a behavior counselor – have been taken away from their school."

"Charter conversion would only work for all families if the charter would take the whole school and all the aspects of the current school. But no charter wants to take on the challenges as they currently are."

Jai Sanders has yet another suggestion: "We're not asking the district or the state just to throw money at the problem but stop throwing these false solutions … We've got a new principal we are happy with; let's give her the time she needs to make things improve."

Should Inglewood be handed over to KIPP, "We will go back to the lottery without the choice of having a neighborhood school," he says, "which seems to be what the district administration wants."

In December, the administration had committed to make a decision about which schools would be targeted for charter takeover: Inglewood or Kirkpatrick, Neely's Bend or Madison. Which would it be?

Regardless of which school is chosen, currently employed educators will likely lose their jobs. Government officials will take credit for having done something. And the next target will for charter takeover will be chosen.

Epilogue

In December, local independent news outlet Nashville Scene reported the MNPS administration had reached a decision to "offer up Kirkpatrick Elementary School," as reporter Andrea Zelinski phrased it, rather than Inglewood, to KIPP. As Zelinski explained, the decision was in many ways a result of the parents from Inglewood speaking out "most vocally against a school takeover."

The following week, the state announced the ASD would take custody of Neely’s Bend rather than Madison, and practically by default, turn the school over to a charter operator.

When Sanders first heard the decision about Inglewood, he recounts in an email, "I immediately gave my first grader a high five and told her 'We did it! We stopped Inglewood from becoming a charter.' … There was an immense sense of relief and accomplishment, but that was tempered with a sadness because I know Kirkpatrick is filled with parents who didn't want the conversion but never got a chance to stand up and be heard."

Shares