With “Becoming Richard Pryor,” Scott Saul mines the comedian’s life to reveal an unlikely star who hit hard at precisely the right time. Pryor’s brilliant cultural explorations -- his icepick wielding of the N-word, his ability to inhabit complex characters -- questioned the very essence of pop culture at a time when all of society’s fabric seemed to be shredding.

Pryor was the perfect comic for the time. When he literally set himself on fire freebasing cocaine, no one was that surprised. Tightrope walkers fall. We were new to what Pryor was revealing, but that we knew.

Saul’s book reveals just how much of a freak experience the Pryor act really was. As one reviewer noted, “Considering both where he came from and the oblivion into which he fell, it’s a wonder he ever reached that peak at all.”

As Saul’s young son plays in the next room, the biographer (and University of California at Berkeley English professor) describes his journey through Pryor’s life, from the comic, writer and actor’s upbringing in a brothel to his unexpected art-world alliances, his unlikely stardom and his horrific treatment of the women in his life. He elucidates what made Pryor, a man of many demons, one of the sharpest social critics of his time.

At the very beginning of the book you describe kind of a classic Richard Pryor sketch in which he's reimagining his childhood beatings. It's such a non-traditional stand-up and really crosses over into performance art in some ways. How is that sketch iconically Richard Pryor's invention?

First of all, I would say that it's not just that he is the adult thinking about what it was like to be the child, it's also the adult thinking about what it's like to be the grandmother. He's really throwing himself into three different positions there and I think that accounts for part of what's innovative in it. The sympathies are very widely distributed in his comedy and he could see things from so many perspectives at once.

On the one hand, you're getting the perspective of the child, who is terrified by this figure of righteous wrath that is his grandmother. She's trying to wallop him into wisdom and wants to make him the agent of his own punishment, where he has to get the switch himself. We also have him playing the grandmother as a kind of sympathetic person who is wrathful but also loving, and those things are all mixed up together. Then you have him as the narrator who can laugh at the perversity and the absurdity of being the child trapped in this situation, appreciating how when his grandmother was beating him for having misbehaved she was turning him into the man he became.

There's so much complexity there, and to me that's really the hallmark of Richard Pryor stand-up. Seeing things from so many perspectives and doing it with amazing finesse, so that the seams don't show... As much as Richard Pryor was transgressive and pushing against every taboo that was alive in American culture, he was also a virtuoso who was able to be a great physical comedian and great storyteller, great voices, all these things. He just folded it all together. By the time you have that sketch in 1978 you have all these things coming together as one.

There are a lot of people out there who think they know Pryor's story just because his sketches are so autobiographical. When he had a fall it made headline news; everybody knew about his worst moments. Why did you want to write his biography? When you first conceived of the project, which part of him did you want to see that you thought hadn't been seen yet?

I think the biographies that existed when I started the project in 2007 were pretty limited. It was true that Richard Pryor had told the story of his life in various forms but what a biographer is interested in is the tension between the story that the figure tells about the life and the history they're passing through — the different perspectives we can get on their life; things that they didn't know about but that crucially shaped them; how other people perceived the events as they transpired.

I think it was very hard for earlier biographers to get that sense of perspective on his life. Earlier biographers did their best, but largely they were amplifying and piecing together the life as he told it. I thought there was a real space for a biographer to go back to his life and reconstruct it, piecing together his account and pitting it against the evidence accrued by interviewing other people who lived through those events. In fact, I discovered that pretty much every major episode of his life was richer and more complex and more bracing than even his stand-up comedy revealed.

I'll give one example of that: We know the grandmother from his stand-up as this fearsome presence seen through the eyes of a grandchild. The grandchild is 6; the grandmother is 55, and that's always affecting how we see her. When you go into old newspapers from Decatur, Illinois, where she grew up, you realize that this was a woman who was fearsome not just to 5-year-olds but to the entire city. She changed the temperature of every room she walked into.

The description of her rise to become a [brothel] madam begins with her walking into a confectionary where she's heard that a black boy has been slapped. She has some kind of cudgel and she starts wailing on the owner behind the counter and she opens a flesh wound, and the woman runs out of the store but Marie does not run. She held her ground. The Decatur police summon five police to subdue her and she remains in the confectionary waiting for the law to come, and then after they book her she presses charges against the store owner.

This is a woman who was born poor, she's black in a city that doesn't give many opportunities for blacks, and she's using the law for herself. She also has her physical strength on her side, so this is a very considerable woman, not just to her grandson.

If she's scary to adults, she must have been absolutely terrifying to a little kid!

You get a sense of the strength his family came from, and how they had found a certain kind of power within the working-class world in which they were located. That strength radiates into his comedy. It's not the only thing that's present there, but it's an important part of it.

There's a scene that really stood out to me, where Pryor tricks a teacher into leading her elementary classroom through the street where all the brothels are. There seems to be a line between that and him wanting to show people this world, which he did later.

It's very important. Pryor was a trickster, but he was a trickster with a purpose. In that incident he is talking to a grade school teacher and she's saying she wants to take her students on a field trip so they can see the world and get a larger sense of what black people do. She wanted to take her charges to see someone who owned a corner store, but Richard Pryor says, "You want them to see the world? I know a great way do to this." At this point he's in high school, like 14 or 15, and he leads her through a red-light district.

The point there is that he hated euphemism throughout his life. Even as a teenager he's thinking that the world is not limited to your respectable corner of it. If you really want to know the world, let's see it all. In that case, the teacher discovers that the world she thought was so disrespectful, a world of ill repute, is in fact full of people who can be sympathetic and caring. During the daytime it looks like a normal street, and that is one of the lessons he's teaching that woman.

I think you're right; there is a connection between that and what he did later in his comedy where he led people down all kinds of streets and avenues that people might have been scared of if they didn't have someone who could pull them through there. Sometimes you didn't know what to expect and you discovered the kind of rich vitality and humanity and complexity of people who live in the taboo zones of American culture.

It took him a while to get there, right?

Yes, yes.

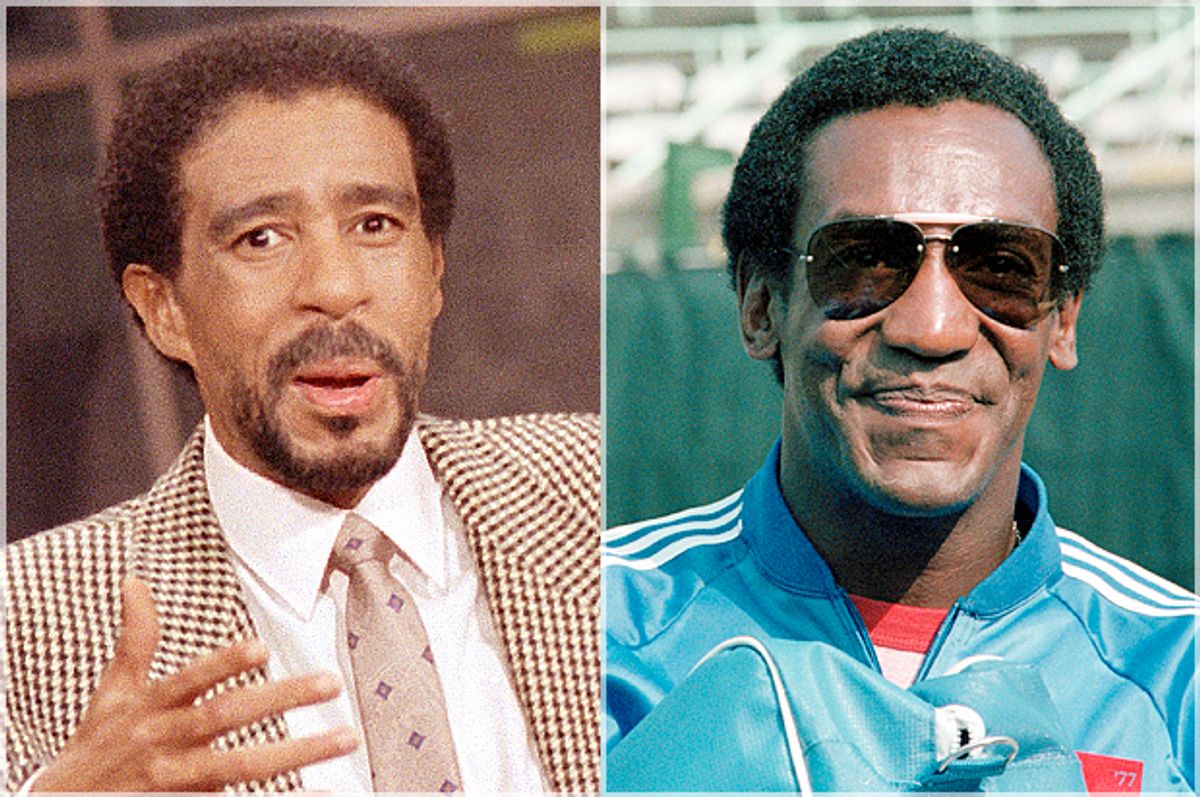

You describe him copying Bill Cosby for a while. He was very envious of Cosby and tried to imitate him.

I think how much he imitated Cosby is slightly overblown in other accounts. Pryor was a young comedian and young artists tend to pick up what's at hand from other figures. When he was beginning, he was very envious of Bill Cosby's success and he tried to replicate some of the storytelling rhythms of Cosby in a few of his sketches. Or if Cosby had a sketch about being on the subway he would create a sketch about being on the subway, so there is that.

From the start, though, I really think he couldn't fit the Cosby mold. He never could become Bill Cosby because Bill Cosby from the start had this cool confidence. He really made you feel like you were in the grip of this ultra-confident storyteller. In a lot of his comedy Bill Cosby chose to sit down because he was so collected — a sit-down comic, not a stand-up comic. Pryor always has this kind of antic expressiveness. He's always going to be Bill Cosby's younger brother; he's always going to be the one who sees himself as the underdog, not the person who occupies his social position with total confidence.

So he's taking from Bill Cosby but he's also learning from people like Jerry Lewis, whose physicality more suits what he wanted to do. There is a persona that Jerry Lewis has, this kind of man-boy, and I think that Pryor has that kind of gawky adolescent aspect to his early comedy.

The book was already published when the recent allegations against Bill Cosby came to light. Did that change the way you thought about Pryor's connections to or differences from Cosby in any way?

Richard Pryor's stance was to always admit his imperfections, to dramatize his imperfections as a way of getting at the world's imperfections, how the world was not living up to its professed ideals. This opened up an incredible space for comedy and for social criticism, so he could see all the ways that America was not living up to its professed ideals. Bill Cosby took another route in that by the time we get into the '70s he's really playing a figure of authority. When we get to "The Cosby Show" he is Cliff Huxtable, America's father. This puts a lot of pressure on him to be the face of respectability, and he basically doubled down on that with the “pound cake speech,” saying that black communities need to rise to this level of the ideal.

Pryor represented a different strategy, which, to my mind, is more accepting and perhaps more profound and more workable as politics. That is to say, everybody is imperfect. Nobody lives up to an ideal unless they're a saint, and those don't exist in the world, generally. We need to recognize that even though somebody's not perfect they still have the right not to be shot in the back; they still have the right not to be choked to death. We need to admit our imperfections as well as press for justice... So I think in some ways that recent events have underlined Pryor's relevance and profundity. Pryor remains terribly relevant.

You talk about all these shifts in American culture at the time Pryor is coming up — the civil rights movement, the Black Power movement, the countercultural movement. How is Pryor a product or a torch-carrier for all those ideas of his time?

As an artist, he brought together elements in the culture that were in conversation but hadn't yet been synthesized creatively the way he synthesized them. For example, in the late ‘60s he's both part of a white countercultural scene; he performs at the first proto-Woodstock held up in Olympia, Washington; he gives a benefit for an anarchist collective. On the other hand, he's also hanging out with more militant Black Power circles. Those two groups don't necessarily hang out together themselves but he's going to bring them together in his comedy.

The counterculture brought some suspicion of rationality; it favored the absurd, it loved surreal flights of the imagination, it was supremely distrustful of the establishment. We have that absurdity, and then you have black power which kind of demystifies the power system of America and speaks truth to power in a way that's forceful and militant. Pryor is bringing these two together in surprising ways. He's taking the zaniness of the counterculture and giving it a point and a trenchancy that it might otherwise lack. Meanwhile, he's bringing to Black Power a kind of ironic sensibility that makes it a little more supple and bendable and able to see the outside of its own politics.

That's Pryor's contribution. He's this crossover figure, somebody like Sly Stone, a person who's bridging these two protest communities.

It's easy to watch his skits and feel so much affection for him, to feel like you're right with him experiencing kind of terrible things as he experienced them, but also to feel like you're right there with him in kind of rebelling against society. It also comes out in your book that he could be pretty violent and brutal at times. How did you come to grips with those aspects of his nature?

I don't know if I ever came to grips with it in the sense of resolving my feelings towards it. My strategy as a writer was to present these two things against each other and give the reader the space to figure out what to make of it. It's clear to me that as an artist he could be so intensely vulnerable, so open to the moment and so open to interplay and collaboration between him and other performers and writers. That's a lot of what makes him beautiful as an artist, that vulnerability and that ability to own the moment of creativity.

His personal relationships have some of that beauty but the more intimately involved you were with him — especially if you were a woman — the more this violent side would come out, the controlling side. I tried to show that this pattern of abuse was deeply rooted in his family. It goes back at least to the 1890s on his father's side of the family, so you can see it, historically, as being a pattern. On the other hand, that doesn't excuse it. I definitely felt that the women who told me these stories were telling me them so that I knew the full man. I felt a responsibility to make their testimonies heard, so I would tell their stories in the vividness which with they remembered them.

How do you think he felt about his transformation from just performing for black audiences into being a mainstream star?

"Comfortable" is not an adjective I would use to describe Richard Pryor, in general. I think he had to be one of the most emotionally conflicted people in the history of America. If we think about who he performed for, in the start he's growing up in Peoria, which is only ten percent black. His first performances in school in the sixth grade are for white audiences, so from the start he's making white people laugh. On the other hand, the same white kids that he's making laugh at these Friday performances are the kids who beat him up during recess and call him the n-word.

This is a recipe for great ambivalence throughout his life. Why is it that the same people who love me when I'm performing treat me in 'real life' with disdain, or as if I'm invisible? He's acutely aware of that throughout his life and it gives a certain barb to his comedy. On the other hand, he does understand that there are some white people who are his allies, his friends, his collaborators and, in terms of the women in his life, his lovers and his longtime companions.

One thing I think he does in his comedy in terms of white audiences is he has these little jabs and these barbs and he's trying to figure out if these are the type of white people who are willing to play with him, to give his relationship to them a kind of electricity and bounce. If they can, he can relate to them. If they see that jab as just being aggression and they bristle and want to run away, those aren't his type of people.

Meanwhile, he's very at home with black audiences this whole time. That's one of the discoveries he makes as he evolves as an artist, that working-class black communities are the core of his support. He wants to give back to those communities throughout his career.

It really is incredible how many different people he was able to hook in with his comedy. What do you think his legacy is? What has he done for the idea of what comedy can be? How did he change things for all of us?

I think his legacy is so various that it's hard to find a comedian who wouldn't claim him as an ancestor. On the one hand you have the spirit of fearlessness; there's a sense with Pryor that he was willing to go to the darkest of places in himself and willing to go to the darkest places in the culture. That is a liberating thing on the level of what you can talk about onstage and how you can talk about it. I think that spirit of fearlessness has inspired so many comedians by giving them the sense that they can follow their nose and go wherever they want.

On the level of technique I think Pryor had so much in the way of chops as a comedian that it's hard to find a comedian who couldn't learn from him. He was a great physical comedian who was able to use his face to make any sort of emotion instantly visible; he was good with his body movements, he had a certain kind of grace and expressivity that was mind-boggling. Then you have him as a great storyteller, a storyteller on par with Bill Cosby, though his stories have a much less leisurely rhythm to them. He's also a joke-teller... he's so many things at once. He can be incredibly experimental, and comedians like Maria Bamford could be seen as following the line of Pryor in really questioning the line between comedy and drama. So much of his work can be totally uncategorizable. You have that black kinds of comedy tradition, that's part of his legacy too.

His legacy is enormous. One thing the poet and critic Amiri Baraka said to me that stuck was that a lot of people heard Pryor's profanity but they didn't get to the profundity. In terms of his comic legacy, people can say any words they want onstage as a result of Pryor, but I think it's the profundity that's the bigger legacy. how can you explore the complexity of your emotional life, your intimate life, and also the complexity of the world around you as a comic? That is Pryor's true legacy.

Shares