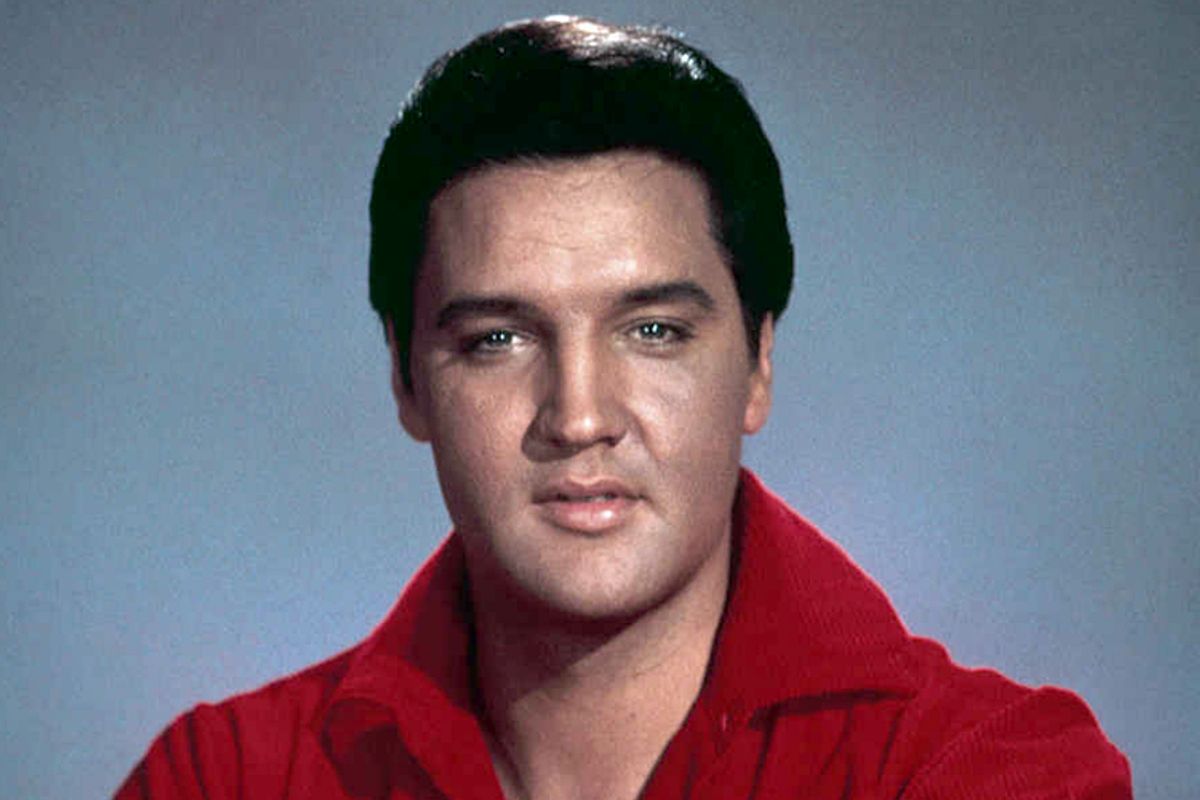

Had he lived, Elvis Presley would’ve turned 80 this month. As with each passing of his January 8th birthdate, I go back to Elvis’ shining moment and enjoy it anew. With evangelical zeal, I talk about it, watch it on YouTube, and share it via social media. The moment isn’t his first Sun recording, 1954’s “That’s All Right,” or his 1956 appearanceon The Ed Sullivan Show, although both of those are pretty great. For me, Elvis’ shining moment is Elvis, his NBC Christmas special, which aired December 3rd, 1968. He was thirty-three, a new dad, and unbeknownst to all, even himself, he was at the peak of his powers. Part of the thrill of viewing the footage is watching fit, glistening Elvis realize this while the cameras roll.

Had he lived, Elvis Presley would’ve turned 80 this month. As with each passing of his January 8th birthdate, I go back to Elvis’ shining moment and enjoy it anew. With evangelical zeal, I talk about it, watch it on YouTube, and share it via social media. The moment isn’t his first Sun recording, 1954’s “That’s All Right,” or his 1956 appearanceon The Ed Sullivan Show, although both of those are pretty great. For me, Elvis’ shining moment is Elvis, his NBC Christmas special, which aired December 3rd, 1968. He was thirty-three, a new dad, and unbeknownst to all, even himself, he was at the peak of his powers. Part of the thrill of viewing the footage is watching fit, glistening Elvis realize this while the cameras roll.

The clownish, Falstaffian Elvis persona is nowhere in sight; the overweight, druggy, ludicrously caped and jump-suited 70s-era Fat Elvis favored by the media, so prominent in the collective memory of the general public, does not yet exist. It rankles me to realize that this sad, bloated, premature-death-bound man, who epitomizes Elvis to most, looms larger than the rock and roll animal of Elvis.

Most people refer to Elvis as “The ’68 Comeback Special,” because it effectively revived Presley’s career for a few years, until pills, food, and mental frailty claimed him. Soon after it aired, Elvis would take his newfound energy and renewed confidence, and spend it well. He released his best album, 1969’s From Elvis in Memphis, a decidedly non-schmaltzy collection of country soul and funky rock, produced by hip session guitarist and co-writer of “Dark End of the Street,” Memphis’ own Chips Moman. The same sessions produced his massive worldwide hit “Suspicious Minds,” which rocketed to the U.S. number one spot, past The Beatles’ “Come Together” and Sly & the Family Stone’s “Hot Fun in the Summertime.” In a spectacular reprieve from decline, Elvis was back, all due to that ’68 special.

ROCK N’ ROLL DEATH KNELL

At the behest of his controversial manager, Colonel Tom Parker, aka the Colonel, Elvis had not performed live since 1961, a year after he was discharged from the U.S. Army, into which he’d been drafted at the height of his initial fame. In the post-50s, pre-Beatles era, crooners like Dion, Bobby Vee, and Frankie Avalon, all anti-Elvii, were ascendant. Elvis and his peers had fallen, sometimes spectacularly, from the public eye.

The blows to rock n’ roll had been relentless: Jerry Lee Lewis’ 1957 marriage to his 13-year-old cousin and subsequent shunning by his fans, Little Richard’s 1957 renouncing of “the Devil’s music” in favor of the ministry, Elvis’ 1958 drafting into the service, Buddy Holly’s 1959 death, and Chuck Berry’s 1959 arrest and subsequent 20 months imprisonment for traveling across state lines with a 14-year-old Apache girl. These incidents – all within twenty-four months of one another – seemed to comprise the cacophonous death knell of a musical form that had only just gotten its wings. The Colonel thought it best to heed the writing on the wall and encourage Elvis’ dreams of being a movie star. Elvis’ first four films, 1956’s Love Me Tender, 1957’s Loving Youand Jailhouse Rock, and 1959’s King Creole, had done well, although Elvis dreamed of, and was promised, films in which he didn’t have to sing. (He would finally get his wish only once, in the tepid 1969 Western Charro!)

Thus, Elvis spent most of the 60s in Hollywood, starring in increasingly uninspired song-and-dance movies – thirty-one scripted films in all – with mostly lame soundtrack albums, from which he made a sizable fortune, both for himself and the Colonel. During this time, of course, JFK happened, the Beatles happened, the Rolling Stones happened, the counterculture, psychedelia and Motown happened, and Elvis, although surrounded by one of the most notorious groups of sycophants ever – the co-called Memphis Mafia – slipped ever more into depression, addiction to pharmaceuticals, and a creeping sense of his increasing irrelevance. He lost his mojo.

CALL IT A COMEBACK

Although his decisions hurt Elvis as often as they helped him, the Colonel deserves credit for the idea of a TV special. Elvis’ movies and soundtracks did worse and worse business, and the Colonel hoped a TV show and subsequent Christmas album would boost the franchise. But the Colonel envisioned a laid-back Andy Williams-type affair, with Elvis lip-synching Christmas songs, which would’ve been terrible.

Luckily, after NBC offered up the funds, young-ish director Steve Binder came on board and insisted the show be more of a rock n’ roll affair, with Elvis doing what had made him famous: rocking out, performing live. Binder knew from rock: he’d directed the classic 1964 concert film T.A.M.I. Show, which starred the Rolling Stones, James Brown, the Beach Boys, the Supremes, and Chuck Berry, among others. For the ’68 special, he put together a Hair-inspired gospel production number, but the bulk of the hour-long show is Elvis, tanned, side-burned, hair dyed deep blue-black, body slimmed down, performing onstage in snug black leather pants, black Beatle boots, and a black leather shirt, while women (and very likely, men) swoon.

The Colonel originally objected to the no-Christmas-carols development, and Elvis was terrified of failing and looking like a has-been, but Binder, who was close in age to Elvis, won the rocker over and, crucially, emboldened him to stand up to the Colonel. He psyched Elvis up like a hype man and, in a rare instance of defiance, the Colonel’s client shook free of the the man’s will. Elvis worked with Binder to show the world what he could really do, what he was about.

1968 was a hell of a year. The assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King had deeply affected Elvis (he strongly suspected conspiracies). While he wanted to project his heretofore slumbering rock god self, he also wanted to infuse the proceedings with messages of racial harmony, anguish over loss, and above all, a shimmering hope.

The Colonel was not happy about any of that. But Elvis and Binder were determined and adamant, and they won the day. That determination informs Elvis’ every gesture, from the moment he looks in the camera in the opening number and sings, “You lookin’ for trouble? You come to the right place / You lookin’ for trouble? Look right in my face” through his medley of hits, until the climactic ending of “If I Can Dream.” That hard confidence, the energy of an adult man with something to prove, up against time and folks who maintain power over him, had never risen to the fore, and would glow only briefly.

ELVIS UNPLUGGED

Paradoxically, the apex of the show comes in the unscripted “unplugged” segment, wherein Elvis jams informally with his pals, including old road buddies, guitarist Scotty Moore – integral to the early Sun recordings – and drummer DJ Fontana, both of whom he’d abandoned a decade earlier when he headed to Hollywood. They play blues, R & B, and rockabilly, and tell stories and make fun of each other between songs. This segment is raw, somewhat lo fi, even occasionally punky. Here more than anywhere else, Elvis often seems possessed, yet controlled just enough, tapped in to a fount of spirit and soul, invoking a carnal essence that hangs about the small studio space like an entity, drawing open multiple mouths and teasing lips into astonished, toothy grins. Elvis glistens with sweat, and thrashes at his guitar as if in a roadhouse. It’s one of the only instances where you get to see and hear him actually play, and he tears it up.

It wasn’t even supposed to happen. During breaks in rehearsals, Elvis took out his guitar and started messing around with his buddies, laughing and singing and carrying on. Binder recognized the power in the moment and invited a studio audience to come watch Elvis shoot the breeze and jam. It’s quite a revelation. The swingin’ 60s crowd – heavy on the girls – gradually becomes every bit as unhinged as Beatlemaniacs, screaming as Elvis, in as stellar voice as he’d ever been, kicks the stage and rises from his folding chair as if lifted by unseen hands.

This is as close as anyone will get to seeing that initial spark Elvis, Scotty Moore, and bassist Bill Black (who’d died of a brain tumor in 1965) ignited in Sun Studios in 1954 when, just fooling around during a break in an otherwise uneventful session, they decided it’d be hilarious if they played Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s “That’s All Right (Mama).” White kids playing a black man’s song! What a hoot! Like Binder, producer Sam Phillips knew he’d stumbled on something special, and decided to immortalize it. He hit RECORD, and here we are.

SHINING MOMENT

What happened? Why did Elvis Presley’s shining moment devolve into a lifestyle that ultimately resulted in him dying of a heart attack at age 42, a mere nine years after such a dazzling success? Two words: drugs and divorce. Although Elvis propelled him back into the spotlight, brought him chart-topping hits, and set in motion several years playing arenas and casinos as a top concert draw, Elvis’ marriage to Priscilla crumbled, he was estranged from his only child, and most tragically, he depended ever more on drugs to function. All of this ruined his physical and mental health.

In one of several tantalizing-yet-excruciating “coulda beens,” Barbra Streisand really wanted Elvis as the male lead, John Norman Howard, in the 1976 remake of A Star is Born. Elvis wanted it, too, but the Colonel insisted on a huge sum of money, and top billing over Streisand, so the part instead went to Kris Kristofferson, and the movie was a massive hit. The next year, Elvis died of heart failure at his home in Graceland.

Rather than dwell on the negatives, however, I choose to make an effort to elevate the ’68 Comeback Special Elvis through whatever means possible, so that maybe one day, when I see an Elvis impersonator, he won’t be representing a seminal artist in decline, sporting a bell-bottomed big belted jumpsuit, but rather, he’ll be clad in black leather, doing his best to approximate the man who rose to meet his acolytes, oppressors, and naysayers with untouchable, if brief, rock n’ roll power.

Shares